Britain —

Its contribution to Socialism,

Marxism and Workers’ Organisation

Links to writings from the history of the British Isles, relevant to the development of socialist ideas and Marxism.

Britain was not the birthplace of capitalism – Northern Italy and the Netherlands have at least an equal claim to that honour – but the early emergence of civil rights, the separation of Church and State, the first bourgeois revolution in 1640, and the British Empire opened the way to the Industrial Revolution and the birth of a truly modern working class. This in turn meant that the first autonomous organisations of the working class (the trade unions) appeared in Britain, and that Britain was at the same time home to radical thinkers, refugees from Europe like Karl Marx, who were able to write and debate in relative freedom.

Certain developments of philosophy in England and particularly the Scottish Enlightenment – “British Empiricism” and Political Economy – were important contributions to socialist thinking, including Marxism. Alongside the French, the English also produced important socialist Utopian thinkers such as Thomas More and Robert Owen. The English working class has always been more conservative than its European counterparts, but it has made a very significant contribution to proletarian organisation and ideas.

One of the first acts of Cromwell after the English Revolution was the colonisation of Ireland. In a sense the conservatism of the English working class is an outcome of the proceeds of colonisation, and thus the question of solidarity with the Irish national struggle has been at the heart of the problem of socialism and the working class in Britain to this day.

The development of Civil Society

The Magna Carta was possibly the first legal document to institute the rights of the citizen against the Divine Right of Kings in European history. Although defending the rights of the nobility who forced King John to sign it, rather than those of the common people, the Magna Carta is an important milestone in the emergence of concepts of Right later to characterise modern, bourgeois society.

Socialism from the Root Up, William Morris

Feudal England, William Morris

The Anabaptists in England, Bax 1903

The Peasants Revolt of 1381 was the first popular uprising organised and led by peasants and labourers themselves. The Peasants Revolt prefigured the Peasant Wars in Germany and the Reformation in Germany.

As early as 1515, Thomas More’s Utopia looked forward to a world of individual freedom and equality.

“in Utopia, where every man has a right to everything, they all know that if care is taken to keep the public stores full no private man can want anything; for among them there is no unequal distribution, so that no man is poor, none in necessity, and though no man has anything, yet they are all rich; for what can make a man so rich as to lead a serene and cheerful life, free from anxieties;”

See Thomas More and his Utopia, Kautsky 1927

The religious warfare and persecution in the 16th century during the reign of Henry VIII led to the establishment of Church of England, separate from the Pope, and ultimately the separation of Church and State. In the Elizabethan period which followed England enjoyed unprecedented freedom of thought, matched only sporadically in Holland and Northern Italy, and later in Germany. At the same time, the British Empire grew enormously and England became the trading center of the world. It was these conditions which led to the development of natural science and philosophy, prior to the Revolution of the 1640s.

The English Revolution of 1640, led by Oliver Cromwell beheaded the King and made Parliament the ruling power. This did not last, and the Monarchy was restored, but after 1640 England was governed by the bourgeoisie, the monarchy retaining only symbolic power. During the English Revolution, the Diggers and the Levellers put forward communist demands, prefiguring the political ideas of the modern working class two hundred years later.

England likes to think of itself as the land of gradualism and reform; the above history shows, however, that like any other society, British society is built on the gains of revolution and conflict.

See Marx on Cromwell and the English Revolution

including England's 17th Century Revolution, Marx 1850

Cromwell and Communism, Eduard Bernstein 1895

Revolutionary History of English Law, Pashukanis 1927

The seventeenth-century revolution, Trotsky 1931

The English Revolution, 1640, Christopher Hill 1940

Cromwell and the Levellers, CLR James May 1949

Ancestors of the Proletariat, CLR James Sep 1949

The Bourgeois Revolution Duncan Hallas 1988

British Empiricism

The peculiarly English national philosophy is Empiricism — the view that the primary source of knowledge is experience (as opposed to the Rationalism of the French, German Idealism (Kant and Hegel) and American Pragmatism). It is generally thought that the British preference for relying on the data of experience and distrust of all theory is a result of being the first country in which the bourgeoisie took state power and made an industrial revolution.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626), a contemporary of Galileo, may be considered the founder of British Empiricism. He advised that if you want to know God then you should look at His works, and he was the inspiration for the British fad for collecting.

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) set out to systematise Bacon’s ideas with a theory of knowledge based on the analysis of the sensations. Hobbes was a royalist, and fled to France after the Revolution, but in many ways he was the philosopher of the bourgeois rule. His characterisation of bourgeois society as “the war of all against all” in De Cive remains essentially the way the capitalists see society. In Leviathan he argued for a strong state to maintain order and even though he may be seen as an early materialist, he favoured the use of religion simply to help maintain order.

A great influence on the direction of British thinking was Isaac Newton (1642-1727). Newton discovered the mathematical language of Nature, and although he his own view of the world was far from “mechanical,” his idea of a God which set the world in motion, and then let it all happen according to laws such as those he had discovered, favoured a mechanical materialist view of the world, eminently suited to the bourgeoisie which was to make the industrial revolution.

Like Hobbes, John Locke (1632-1704), developed a theory of knowledge based on knowledge derived by the processing of sense impressions. Locke is most remembered however for working out the basic principles for bourgeois government, separation of powers, elections, the principles of law, etc.

David Hume (1711-1776), along with Adam Smith, was the leader of the Scottish Enlightenment. Hume showed that however much we studied the regularities in Nature, in principle, we can never have knowledge of causes. Hume is thus the founder of modern scepticism. Hume was also one of the founders of bourgeois ethics and visited France in the lead up to the French Revolution where he exerted considerable influence over the subsequent development of French philosophy. His scepticism also stimulated Immanuel Kant in his enquiries.

Another Briton who exerted considerable influence on the French Revolution was Thomas Paine (1737-1809), an Englishman who never received any attention in England, but visited American and brought the ideas of the American Revolution and its Declaration of Human Rights back to France.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), son of the political economist James Mill and a contemporary of Karl Marx, was along with prison reformer Jeremy Bentham a founder of Utilitarianism (economic science expressed in the language of ethics), to this day the dominant theory of Ethics in the English-speaking world. J S Mill was also a precursor of modern economic science and one of the theorists of the modern British system of government (Britain does not have a Constitution).

With the growing influence of natural science, England also had its positivists, such as Herbert Spencer (1820-1903).

Oriented as it is to facts, this outlook of the British bourgeoisie, is ill-fitted for revolutionary idealism. Nevertheless, it exerted a powerful influence on European thought; the French Revolution valued the materialism of British Empiricism and adapted it for their own struggle against Theism, giving it a more revolutionary flavour in the process.

Marx and Engels on British Empiricism

British bourgeois ‘morality’, Trotsky

The Philosophy of British capitalism, Trotsky

See Philosophy Subject Archive.

Political Economy

The principal contribution of the British bourgeoisie to socialist theory is political economy. The founder of English political economy was Sir William Petty, but its foremost exponent was the Scotsman Adam Smith. Smith was a close friend of David Hume. His first major work was the Theory of Moral Sentiments, which he completed in 1759. 17 years later, in 1776, he published The Wealth of Nations, and moral philosophy — the consideration of what people should do — had been transformed into a “branch of science,” concerned with immutable laws determining what people must do. For the next two hundred years, Britain would be the home of Political Economy.

Hegel studied the writings of James Steuart (1712-1790) and saw in British political economy an understanding of how the World Spirit acted “behind the backs of people,” manifesting itself in the course of History.

Thomas Malthus (1766-1834), who developed a reactionary theory of population was also influential in the development of Darwin’s theory of the Evolution of species.

David Ricardo (1772-1823) was considered by Marx to be the most important of the political economists. The very fact that Ricardo’s theory was riddled with contradictions, Marx regarded as its strength.

James Mill (1773-1836), also a social reformer and Utilitarian, may be best known to Marxists because of the very important early work of Marx, Comments on James Mill.

John Stuart Mill was the first to make a positivist critique of political economy, but he was not able to make the transition to modern economic science, based on marginal utility.

William Stanley Jevons was the English representative of the new “Marginal Revolution” which initiated modern economic science, while

Alfred Marshall (1842-1924) continued the approach of political economy even after the Marginal Revolution had led European thinkers to take a new direction, in which value was regarded as a metaphysical entity, focused on price and utility, though Marshall sought to avoid using the term “value,” his work remained true to the traditions of Political Economy.

John Neville Keynes, (1842-1924) was one of the last English political economists of the classical school. His son, John Maynard Keynes, (1842-1924) devised the macro-economic ideas which dominated post-World War Two capitalist development, including the Bretton Woods institutions.

Keynes believed that government intervention in the economy could prevent crises like the Wall Street Crash and the Great Depression. His theories were finally eclipsed when the centre of political economy moved to the U.S.A. in the 1980s with the emergence of Milton Friedman’s Monetarism.

Karl Marx lived in London from 1850 till his death in 1883, and most of his time there, particularly the first 15 years, was spent studying political economy. Marx saw in this theory, a window into the ideology of bourgeois rule. By critique of political economy, Marx hoped to outline the practical direction for the overthrow of bourgeois society, whose structure was mirrored in the theories of the Political Economists.

See Marx on Political Economy.

Classics of British Political Economy

Political Arithmetick, by Sir William Petty 1690

Consequences of Lowering of Interest, by John Locke 1691

Theory of Moral Sentiments, by Adam Smith, 1759

Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy, by James Steuart, 1767

The Wealth of Nations, by Adam Smith, 1776

An Essay on the Principle of Population, by Thomas Malthus, 1798

Grounds for Restricting Import of Corn, by Thomas Malthus, 1815

Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, by David Ricardo, 1817

Elements of Political Economy, by James Mill, 1844

Utilitarianism, by John Stuart Mill, 1863

General Theory of Political Economy, by William Stanley Jevons, 1866

Principles of Economics, by Alfred Marshall, 1890

General theory of Employment, Interest & Money, J. Maynard Keynes, 1936

Natural Science

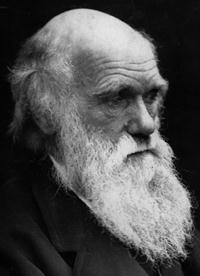

Throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, Britain was also the home of the most advanced natural science (except for mathematics, which after Isaac Newton, was mostly developed on the Continent, and with the rise of the natural and social sciences in Germany in the 19th century). One of the scientists who was most influential for the development of Marxism was Charles Darwin (1809-82), whose theory of Evolution provided a natural scientific basis for key ideas such as the determination of development by contradictions in the mode of production and reproduction, the origin of the human species in Nature and dialectical development incorporating both continuity and discontinuity of leaps.

See Marx and Engels on Natural Science.

In 1931, a number of leading Bolsheviks and Soviet scientists visited London for the International Congress of the History of Science and Technology, and partly as a result of this intervention, a number of leading British scientists became advocates for Marxism: J.D. Bernal (1901-1971), for example. Other British scientists, such as J B S Haldane (1892-1964), have been forthright advocates for philosophical materialism and socialism, and more or less sympathetic to Marxism.

J.B.S. Haldane Archive

J.D. Bernal Archive

Utopian Socialism

Britain has also contributed to the development of socialist ideas through its Utopian Socialists. Thomas More, who coined the word “Utopia” – literally “nowheresville,” sketched his idea of how the world could be 450 years ago. Robert Owen (1771-1851) set about putting Utopian ideas into practice by building a model township called New Lanark based on his own mills. In the 20th century, H.G. Wells extended the Utopian idea through the new medium of Science Fiction.

A New View of Society, Robert Owen 1816

The Development of Utopian Socialism, Engels

Forward to Thomas More‘s Utopia (1893)

The Utopists (1886) William Morris

The Women’s Movement

As the first country to break down the rigidity of traditional society, British also threw up exponents of the first wave of feminism, — Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1997) and Harriet Taylor (1856-1915) being the most famous. The English revolutionary socialist and Suffragette, Sylvia Pankhurst (1882-1960), was the leader of the left-wing in the second wave of women’s liberation.

It was certainly no accident that Sylvia Pankhurst, the most radical leader of the women’s movement in England, was also a socialist and supporter of the Russian Revolution.

Elsewhere, the other leaders of the second wave of feminist agitation were also communists; women such as Clara Zetkin in Germany, Rosa Luxemburg in Germany/Poland and Alexandre Kollontai in Russia, were leaders of the Marxist wing of the socialist movement in their own countries. Workers and women were united in this period in the fight to extend basic democratic rights.

Women & Marxism Subject Archive

Mary Wollstonecraft Archive

On Wages, Marriage and the Church, Connolly and DeLeon, 1904

Sylvia Pankhurst Archive

The Trade Unions

The basic unit of organisation of the bourgeoisie – the company, and the basic unit of the working class (in Britain) – the union, both grew out of the same source, the late medieval company, formed by tradespeople in the towns to protect their interests, offer mutual aid to members when in trouble, pursue charitable ventures, and so on. Some of these went on to become powerful capitalist companies, some became self-defence organisations of skilled employees, defending their interests both against the competition of unskilled outsiders and their employers.

Thus in Britain, trade unions emerged spontaneously, independently of any political party. Working class political parties only emerged much later (see below) as unions sought to extend their effectiveness by intervening in the debates in Parliament, and later embracing the revolutionary struggle for socialism.

The Luddites and the Combination Laws History Archive.

Marx and Engels:

On Primitive Accumulation

On the Factories and the Condition of the Workers

The unions were subject to brutal repression, particularly in the early 19th century, until eventually establishing the basic right to organise with the repeal of the Combination Laws in 1824. Repression continued however, and in 1834, the Tolpuddle Martyrs were transported to Australia under old laws, triggering the Chartist Movement.

See Marx and Engels on The Chartists.

See The Chartist Movement History Archive.

The Chartist Movement was the first independent political movement of the working class in Britain, developing at the same time as the early communist movement in the Streets of Paris. The Chartists saw that even freedom to form trade unions was not enough, workers had to fight for political power.

The 17-century revolution and Chartism, Trotsky, 1925

One of the most famous struggles of the English trade unions was fight against the Corn Laws, in which the unions made common cause with the Industrialists against the Tory establishment and Landowners.

Engels on the Labour Aristocracy & “New Unionism”

The Working Class in the 19th Century, Trotsky

The Industrial Revolution in Britain and

Political Movements in England, William Morris 1886

On the occasion of a sensational trial (1895)

My Years of Exile (1915) Eduard Bernstein

The New Mass Unions.

In the late 19th century, a movement grew up known as New Unionism, in which mass unions of unskilled workers emerged for the first time – and it was a strike by young women which launched the struggle for New Unionism!

- The Bryant & May Matchgirls strike of 1888;

- The Dockers’ Tanner of 1889, led by Tom Mann (1856-1941), Ben Tillett (1860-1943) and John Burns (1858-1943); and

- The Gasworkers strike of 1890, led by Will Thorne (1857-1946) and Eleanor Marx (1855-1898) which won the 8-hour day for gas workers;

- Engels on the “New Unionism”

The Intellectuals & the Workers Kautsky 1901

Trade Unions and Bolshevism, Trotsky

These mass unions were militant, open, democratic and egalitarian and were committed to the struggle for socialism in a way that the earlier unions of craftspeople which emerged out of the medieval period never were.

In the General Strike of 1926, the Miners brought British capitalism to its knees. This was the greatest movement of the British workers and only stopped short of seizing political power because its leaders lost their nerve. Right up recent times, the British trade unions continued to challenge the power of Government, bringing down Ted Heath’s Tory government in 1973 and destroying the Callaghan Labour Government in 1979.

See the General Strike History Archive.

The situation in Britain 1925-1926, and In Retrospect, Trotsky

By Duncan Hallas

The Communist Party and the General Strike 1976

The First Shop Stewards' Movement 1973

The White Collar Workers 1974

The CP, the SWP and the rank and file movement 1977

Some Prospects 1977

A Clearer View 1979

The making of a working class historian (E.P. Thompson)

A Soldier's Story 1995

Britain went into decline as a world power after the First World War and gradually lost its Empire, while England, once the “workshop of the world,” became a financial centre surrounded by rusting industry.

By Michael Kidron

The Decline of British Capitalism 1957

After the end of Empire 1960

The Limits of Reform 1960

Socialism in Britain

In Britain, it was the unions which built the political parties, not the other way around. Just as it was the Trades Council leaders of the 1850s and 1860s who promoted the formation of the International Workingmen’s Association, it was the leaders of the new, mass unions who were the foundation of the Socialist-Democratic parties in Britain, the Labour Party and later the Communist Party and Trotskyist parties of the post-World War Two period.

See the Working-class Internationalism History Archive.

The International Workingmen’s Association

The first efforts to create international workers organisations – the League of the Just and the Communist League – were organised in London. As Stekloff outlines in his History of the First International, the First International of which Karl Marx came to be the leader, was preceded by earlier attempts by Chartists such as Ernest Jones and Julian Harney, who came together with European political refugees such as Wilhelm Weitling and Karl Schapper, in the Fraternal Democrats in London.

See The First International History Archive.

In its early days, the International was made up of mainly exiled German communists and English Trades Council delegates, with some French Proudhonists and others, and as it grew, English trade unions signed up their entire membership to the International. During the decade of its activity, the International planted unionism in the nascent workers movement right across Europe.

Social Democracy in Britain

The English trade unionists always constituted the most conservative section of the revolutionary workers movement, even though it is in Britain that Socialism penetrated most deeply into the working class. The First International declined after the crushing of the Paris Commune in 1871, and when the Second International was launched in 1880, it was convened in Europe. It’s British affiliates were always far smaller than, for example, the German Social Democratic Party, which numbered its members by the million.

Letters on Socialism in England Marx & Engels, 1881-1894

See the Social Democracy History Archive.

William Morris Archive (1834-1896)

Henry Hyndman Archive (1842-1921)

Dora Montefiore Archive (1851-1933)

Eleanor Marx Archive (1855-1898)

Ernest Belfort Bax Archive (1854-1925)

Theo. Rothstein Archive (1871-1953)

See also the journals published by Social Democracy in Britain:

Anarcho-syndicalism and Antiparliamentary Socialism

The Anarchist International never recruited a section in England, but the Social Democratic Federation was split between Marxists (who supported the perspectives of the German Social Democrats to build a mass parliamentary party) and antiparliamentarians (who favoured achieving socialism while bypassing parliament). These ultra-left socialist agitators, predecessors of the IWW, included Joseph Lane, Frantz Kitz and Sam Manwairing; William Morris, it is said, wavered between the two wings. Later on, the IWW found a small following in Britain and some of the Suffragettes, such as Sylvia Pankhurst were anti-parliamentarian socialists. Kate Sharpley was an early English anarchist.

See section on the Socialist Party of Great Britain, a party founded by members of the S.D.F. expelled on charges of “impossibilism,” which continues to advocate a purist vision of socialism from its founding in 1904 one hundred years later.

Reformism

Through bitter struggle, the English workers were the first working class to gain basic democratic rights and the right to organise. On top of this, the British ruling class was deriving the majority of its wealth by exploitation of the colonies, so it could afford to offer concessions and co-opt the “aristocracy of labour” – the skilled workers and union leaders who were leading the English working class. Consequently, the English working class (not so much the Irish, Scottish and Welsh workers) has always been inclined more towards reformism than revolutionary socialism.

See Reformism in the glossary.

Mr. Baldwin and ... ‘gradualness’, Trotsky 1925

Peculiarities of English Labour Leaders, Trotsky 1925

The Fabian ‘theory’ of socialism, Trotsky 1925

George Bernard Shaw Archive (1856-1950)

Bertrant Russell Biography (1872-1970)

Dialogue with Bertrand Russell, Henry Brailsford and Leon Trotsky

By Tony Cliff

The Economic Roots of Reformism 1957

Incomes Policy, legislation and the Shop Stewards 1966

The bureaucracy Today 1971

After Pentonville: the battle is won but the war goes on 1972

1972: A great year for the workers 1973

The balance of class forces in recent years 1979

Patterns of the Mass Strike 1985

The Class struggle in the 90s 1992

Labour's crisis and the revolutionary alternative 1996

The Labour Party

On 27th February 1900, following the lead of their Australian cousins, 129 representatives of the Trade Union Congress, the Independent Labour Party, the Social Democratic Federation and the Fabian Society, met at Memorial Hall, Farringdon Street, London.

Keir Hardie moved a motion to establish

“a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour.”

The Conference established a Labour Representation Committee including seven trade unionists, 2 delegates of the Independent Labour Party, 2 from the Social Democratic Federation and 1 from the Fabian Society. After the 1906 General Election, which saw 29 Labour representatives in Parliament, the LRC became known as the Labour Party.

In 1923, Ramsay MacDonald, who had been a member of the Independent Labour Party and Secretary of the Labour Representation Committee, became Prime Minister of a minority Labour Government. Although MacDonald had been in a minority within the Labour Party in opposing the First World War, MacDonald’s name has gone down in history as that of a labour-traitor – he opposed the 1926 General Strike and in 1931, while Prime Minister, he was expelled by the Labour Party, but kept on as leader of a National Government controlled by the Tories.

Over the years, the capacity of the trade unions to control the behaviour of Labour Party members of Parliament has declined even further. Today’s “New Labour” has broken almost all ties with the trade unions and the broader workers’ movement.

Labour's Addiction to the Rubber Stamp, Tony Cliff 1967

The Communist Party of Great Britain.

The Communist Party of Great Britain was formed in July/August 1920 and sent a delegation to the Second Congress of the Communist International including Dick Beach of the IWW (Industrial Workers of the World), Tom Welch of the Social Democratic Federation, the Scottish shipyard worker Will Gallacher, John Murphy of the DeLeonist Socialist Labour Party, J T W Newbold, a Fabian, the Left Communist, Sylvia Pankhurst.

John MacLean, a Scotsman, was perhaps Britain’s greatest communist – a leader of the militant workers of the Clyde, a member of Hyndman’s Social Democratic Federation, the first and loudest opponent of the War, who was made honorary Soviet Consul in Glasgow in 1918. In the end MacLean did not join the Communist Party and became a Scottish nationalist.

See Communist Party of Great Britain website.

See Should we Participate in Bourgeois Parliaments?

and “Left-Wing” Communism in Great Britain, Lenin 1920

Although its founders came from the extreme left of the workers movement and were the real leaders of the General Strike in 1926, Stalin was concerned to use the Communist Party to neutralise the threat to the Soviet Union posed by British imperialism, and the British Communist Party came to be one of the more conservative sections of the Communist International. Nevertheless, Communist Party members held leadership positions in the most militant trade unions up until the Party was dissolved. A number of important historians, scientists and intellectuals belonged to the Communist Party, especially during the 1930s through to the 1950s.

As the impact of the suppression of the Hungarian Uprising, the Sino-Soviet Split, the Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia, betrayal of the Algerian independence struggle and the May/June 1968 demonstrations in Paris, began to bite, and the British Party followed its European sisters towards distancing itself from the Soviet Union, and the Party began to fracture.

In 1977, a group of Communist Party leaders who disapproved of the “eurocommunist” direction of the Party left to form the New Communist Party of Britain.

In 1988, the Editorial Board of the Communist Party's daily paper, The Morning Star, split from the Party and formed the Communist Party of Britain, more oriented to the labour movement than the leadership at that time.

After the break up of the USSR in 1991, the CPGB decided to disband, and renamed itself Democratic Left.

See the Comintern History Archive.

Communism and Stalinism by Duncan Hallas

The Trotskyist Movement in Britain

Supporters of Leon Trotsky emerged in Britain in 1932 when Reg Groves, Harry Wicks and Henry Sara were expelled from the Communist Party after raising criticisms of the Comintern’s “social fascist” policy which had allowed Hitler to come to power in Germany. Until the 1960s, the Trotskyists mainly existed as ‘underground’ groups inside the Labour Party where it was possible to challenge the Labour leadership and organise in relative freedom.

The ‘Balham Group’ they formed, in particular the Revolutionary Communist Party formed after a split in 1938, continued inside the Balham Branch of the Labour Party and produced all the leaders of the Trotskyist groups to form over the decades to follow – Gerry Healy and Mike Banda (SLL), Tony Cliff (IS), Bob Pennington (IMG) and Ted Grant (The Militant Group).

See The Balham Group. How British Trotskyism Began.

See the Archives of the following, who were members of the Trotskyist movement in Britain:

C L R James (1901-1989, born in Trinidad)

Ted Grant (1913-2006, Militant, born in South Africa)

Tony Cliff (1917-2000, IS, born in Palestine)

Duncan Hallas (1925-2002, IS)

Jim Higgins (1930-2002, IS)

Michael Kidron (1930-2003, IS)

Geoff Pilling (1940-1997, SLL)

Cliff Slaughter (SLL)

Trotskyist Newspapers in Britain

Workers International News, a Trotskyist paper published in London by the Workers International League, 1938-1944; Revolutionary Communist Party, 1944-1949. Monthly, later irregular. Theroretical organ of the WIL and then the RCP until the dissolution of the party in 1949.

Labour Review, published in London from 1952 until 1963 by the tendency associated with Gerry Healy. Originally it appeared very sporadically but from 1957 it appeared more regularly. From 1957 until 1959 it was one of the finest non-sectarian theoretical journals on the left internationally. It was replaced by a journal called Fourth International in 1964.

International Socialism, originally published in 1958 as a by the Socialist Review Group then working in the Labour Party. The index is divided into three parts: 1958-1968, 1969-1974 and 1975-1978.

Marx’s Exile in London

Like many other German communists, Marx fled to London in 1850 and was to live the rest of his life in England, being buried at Highgate Cemetery in 1883. During his early years in London he mostly associated with fellow refugees in the Workers Educational Society and similar groups.

See Heroes of the Exile, 1850

Later on he was invited to join the General Council of the International Workingmen's Association, and from 1864 he was intensely involved with the affairs of the working class in Britain as well as on the Continent.

See Marx on the International Workingmen's Association

The British Empire

Two factors contributed to Britain becoming the most powerful nation in the world until the early twentieth century – the early development of civil society, and the English Revolution which removed impediments to the expansion of capitalism and the Industrial Revolution which began in England, and the British Empire by means of which England sucked the wealth from the farthest corners of the globe. This dominance contributed to the conservative nature of the English working class, despite its history of bitter struggle to establish its own rights. It also meant that the ideas of the English workers, especially its trade unionism and reformist politics, spread to the colonies, especially the settler colonies such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

See Marx and Engels on British Colonialism

Germany, England and the World-Policy, Kautsky 1900

Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Lenin 1916

and Britain and Military Strategy, Trotsky

Ireland

England's first colony however was its closest neighbour, Ireland. It is rightly said that the English working class will never be able gain its own emancipation until its has through solidarity with the Irish workers, lifted the yoke of British imperialism from Ireland.

See Marx's Letters on Ireland and the Fenians

See Ireland, Kautsky 1922

See discussion on The National and Colonial Question at the Second Congress of the Comintern 1920

See the forthcoming Irish History Subject Archive ...

Good English History Sites:

Spartacus Educational (this is one of the best sites on the Internet!)

TUC Online History (a very rich resource)

Medieval Sourcebook

The Web of English History

Aspects of the Industrial Revolution in Britain

Archive maintained by Andy Blunden.