The balance of class forces in recent years(Autumn 1979) |

From International Socialism 2 : 6, Autumn 1979.

Reprinted in Tony Cliff, In the Thick of Workers’ Struggle, Selected Works Vol. 2, Bookmarks, London 2002, pp. 373–421.

Transcribed by Artroom, East End Offset (TU), London.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

There have been dynamic changes in the balance of class forces in Britain over the last few years. We need to find out in what direction the balance has been tilted, and what the causes were.

In Place of Strife argued that shipyards, mining, docks and motor vehicle manufacturing, employing some 4 percent of the labour force in Britain, were the industries most prone, by far, to strikes. In 1965 these industries were responsible for 53 percent of all strike days in the country. [1] The specific weight of these industries in the general workers’ front is much greater even than the figures show, because of the high level of concentration of workers’ power in them. As they are at the heart of the class war, let us follow the history of disputes in these industries in recent years.

It was the struggle in Upper Clyde Shipbuilders that radically turned the tide of the Tory attack. After the defeat of the power workers in December 1970 and the postmen after a seven-week strike, and the sell-out of the Ford workers by Jones and Scanlon after a nine-week strike, the UCS workers took over the yards – one week after the Industrial Relations Act came into being.

Already in June 1971 there were strong rumours of mass sackings threatening workers in UCS. On the afternoon of 24 June over 100,000 workers in Glasgow stopped work and half of them marched in a demonstration through the town. The demonstration included representatives from every factory in the west of Scotland, as well as delegations from over the border. This was the largest Clydeside protest demonstration since the General Strike. On 29 July John Davies, the secretary of state for industry, got up in the House of Commons to announce that employment in UCS would be cut from 8,500 to 2,500. Next day the workers of UCS took control over the four yards.

On 10 August a meeting in Glasgow attended by over 1,200 shop stewards from all over Scotland and the north of England unanimously endorsed the plan for a work-in, and appealed to all workers to give financial support to the workers of UCS.

On 18 August some 200,000 Scottish workers downed tools, and about 8,000 of them went on a demonstration in support of the UCS workers.

Millions of workers from all over Britain contributed financially to the long drawn-out battle. UCS workers were the first to breach the Industrial Relations Act, and even Harold Wilson had to admit in an introduction he wrote to a book by Alasdair Buchan, The Right to Work: The Story of the Upper Clyde Confrontation:

But for the men who work on the Upper Clyde, this story would have followed its conventional course: meetings between management and men would have resulted in failure to agree; the inevitable sackings would have been accompanied by forlorn protest; the dole would have been started and the story would have ended ... What the men of the Clyde proclaimed ... was “the right to work”. [2]

In trade union terms the shipyard industry has long been one of the most highly organised industries in the country. Skilled tradesmen have remained dominant in a way which is true of few other industries. In 1963 just over 60 percent of all manual workers in shipbuilding were skilled [3], and their role in production is central. As a consequence the division of labour and the demarcation between skills was more extreme than in any other industry. The workers had a deep attachment to the industry. Thus a study of one shipyard on the Tyne carried out between 1968 and 1970 reported:

... 86 percent of the Boilermakers interviewed, 79 percent of the outfitting workers and 61 percent of the semi-skilled had spent more than half of their working life in the industry, and as few as 7 percent of them had preferred a past job outside shipbuilding and marine engineering. (In contrast only 38 percent of the unskilled men had spent more than half their working lives in the industry and one in five of them preferred a previous job outside the industry.) [4]

Shipyard workers have for a long time been tough fighters. Already in 1888 the proportion of trade unionists among them was higher than in any other industry – 36 percent of shipyard workers were members of trade unions, while among general engineers the proportion of trade unionists was 15 percent, among miners 19 percent, textile workers 8 percent, railwaymen 9 percent, and print workers 21 percent. In 1901 the proportion of shipyard workers was as high as 60 percent. [5]

And they were accustomed to long and bitter struggles. Thus, for instance, Shipsmiths in the north east went on strike from November 1904 to June 1905, resisting wage cuts. [6] In April 1908 some 13,000 shipyard workers in Scotland and north England were locked out and held grimly on for a very long time. [7]

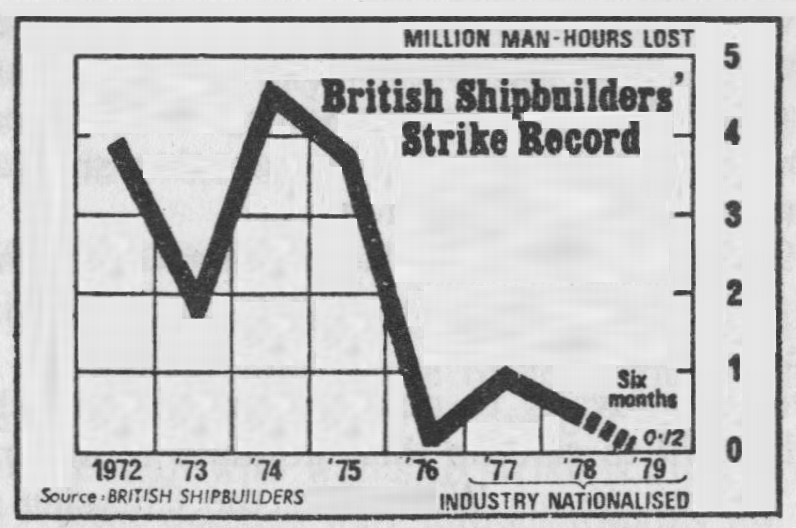

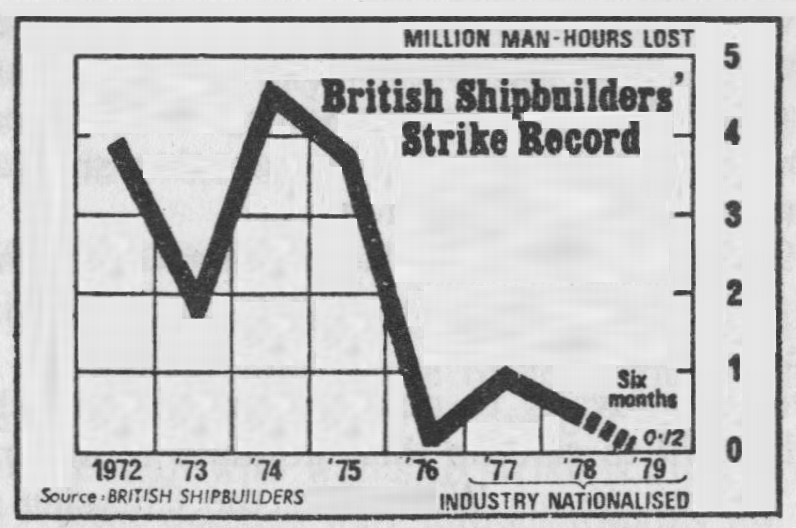

Since 1974 the struggle has declined drastically, as shown in the following graph [8]:

|

Actually the strike statistics do not tell us the whole story. Shipyard workers have been so depressed and demoralised that they accepted very poor terms. Thus, for instance, 3,500 workers of the Tyne Group of Shiprepairers, in exchange for the 10 percent allowed by government guidelines, accepted the abolition of demarcation restrictions, complete flexibility, and gave a year’s no-strike guarantee. [9]

The 168 different bargaining units, which gave power to shipyard workers to push wages up through drift, leapfrogging, etc, were completely given up, and a national wage agreement substituted for them which gave a same day settlement for the whole industry. [10]

In fact Govan, the new name for three of the four former UCS yards (the fourth being Marathon), had been pioneers in the working of a joint union-management monitoring committee for a harsh productivity deal.

They signed a 31-point agreement containing elaborate no-strike pledges, massive concessions on work practices giving management the right to impose compulsory overtime. The agreement at Govan’s has since been used as the model of what British Shipbuilders hope to achieve throughout the industry. In addition to the main points, the agreement also states quite clearly, “Any changes required that will help make the company more efficient will be introduced at any time subject only to the normal process of consultation and mutual agreement.” Govan expects to get the number of man hours to build a ship down from 850,000 five years ago to 400,000 next year. Naturally, in a declining market such productivity increases can mean one thing only – massive redundancies.

Govan reached the lowest depths when they scabbed on their Tyneside Swan Hunter brothers.

Management tried to impose a declaration of intent on the Swan Hunter workers as a precondition for giving them a big proportion of the Polish order. The Swan Hunter workers rejected it. Dave Hanson, chairman of the outfitters’ shop stewards committee, said, “There is a major principle at stake. If we give in, every time the government wants a contract it will try and impose conditions”. [11]

When Swan Hunter workers blacked the Polish ships Jim Airlie rushed to take the job – the same Jim Airlie, one of the workers’ leaders at UCS in 1971, who asked at that time, “Are the other shipyards going to accept our orders and let my men starve?”

But by 1979, during the Swan Hunter dispute, he sang a new tune: “If Newcastle are losing six ships through disputes, we will build them. If not us, then the Japs will.”

To prove their loyalty to management Govan shop stewards agreed in July 1979 to give up their holidays in order to complete Polish ships in time – i.e., as Willie Lee, the Chrysler AUEW shop steward, put it, “in order to close the shipyard on time”.

This abysmal betrayal of every trade union principle is taking place in an area where unemployment is overwhelming.

In February 1972 the miners broke the incomes policy of the Heath government. Using the flying picket that culminated in the mass picketing of Saltley depot, they brought the government to its knees. In 1974 the miners managed to bring down the Tory government.

But since then the NUM has accepted Phase I, Phase II, Phase III and Phase IV of the government guidelines. To add insult to injury, they accepted a most divisive and injurious productivity deal.

For some idea of how divisive it is let us look at a few facts. In South Nottinghamshire the area average bonus for face workers was £27 in the week ending 11 March 1978. At Gedling pit in Nottinghamshire the miners are on a face-by-face deal, and payments vary from £6 to £28. Annesley is also on a face-by-face scheme, and bonuses vary from £17.50 to £45. [12]

Compare the above bonuses with those earned in Maltby pit, South Yorkshire. In a typical ten-week period in the winter and spring of 1978 they varied from precisely 28p per week to £4.14 – an average of less than £2 per week. [13]

The division is not only between miners of different pits, or even different faces in one and the same pit, but also between surface workers, usually injured and older men, and face workers, with pay differentials of £50-£60 compared to £20 four years ago.

And the reaction of the miners to the government guidelines? One militant miner from Armthorpe Colliery near Doncaster says, “The national executive ... decided to accept the 10 percent deal and not allow a ballot of miners in case we rejected it.

“What happened in the rank and file? Nothing! We sat at home and watched Crossroads as though it was happening to someone else”. [14] The high wave of miners’ battles of 1972 and 1974 gave way to a very low level of activity (with one very important exception to which we shall refer below – the spontaneous strike in support of the rescue men in May 1978).

The number of strike days lost – over 10 million in 1972 and over 5 million in 1974 – declined to 52,000 in 1975, 70,000 in 1976, 88,000 in 1977, and 176,000 in 1978. [15]

Lord Devlin, in his report on the docks in 1965, complained that the dockers had “an exaggerated sense of solidarity or loyalty” – men accepted without question a policy of “one out, all out”, adopting the “principle that the man who wants to strike is always right”. [16]

In July 1972 the dockers were unquestionably the heroes of the whole working class. Throughout the first few months of 1972, fighting to defend their jobs, they courageously faced up to the government, the police and the National Industrial Relations Court.

The rank and file showed fantastic initiative. They decided on their own to take action in defence of jobs threatened by employers using non-registered dockers and cheap labour. As Mickey Fenn, one of the most active rank and file leaders in this campaign, put it:

It was obvious we had to do something about the containers so we began picketing at the same time the Tories were introducing their Industrial Relations Act, but we didn’t think it would be a danger to us; but just in case, we made over our houses and cars, etc, to our wives and arranged that if the top four stewards were lifted there would be another four to take their place, and then another four.

When we heard they were planning to arrest three of us outside Chobham Farm there were 3,000 of us and about as many police. The SPG didn’t exist in those days, but there are only 250 of them and 3,000 of us would have given them a hard time. Anyway, later on some bailiff came down but all he got was a rolled umbrella in the ribs, two of them cracked – some dockers do carry rolled umbrellas.

At the same time we began to spread our picketing to more container ports. We would tell any lorry that threatened to cross the picket that they would he blacked in every port in the country. Then we began following the lorries and we followed them all, up to 200 miles we went, and every time a lorry went into a place we would follow.

Well, one day the port shop stewards were having a meeting and we heard four or five of us were to he arrested. Well, anyway, we had decided that it was better for some of us to be arrested than fight the police in the streets, because we could build up a campaign round this. When it happened we immediately decided to shift the centre of our picketing to Pentonville prison and make that the organising centre for our operations. The docks had come out immediately they heard about the warrants, and this went for all the docks all over the country. The problem was that the Tories had planned it so that we would be fighting when every car plant, mine and engineering factory would be closed for the summer. The big problem was how to get around all the different places arguing with each one why they should be out: it took a long long time to argue with each one.

At this time the press was going on about how we had vast financial and organisational resources, but I can tell you, because I was treasurer of the port shop stewards’ funds, that we began with £4 – but this gradually built up. We had collections among our own lads and donations from outside.

One thing we found out was that if you give people a chance they really can have great imaginations. When we had the posters people asked me, “Where should we put the posters?” but I said, “Wherever you think there should be posters put them up,” so posters appeared all over the place – on Buckingham Palace, Lambeth Palace. The NF HQ in Croydon was plastered. We tried the Tory headquarters but policemen were outside so we left it. Transport House was already done when we got there. One bloke managed to get right up the outside of the Bank of England, and I’ll never work out how he did it without ropes.

It wasn’t easy bringing out Fleet Street, I can tell you, but we went right up there and said to the FOCs, “Look, your unions were always the ones at the front of the anti Industrial Relations Act demos, and you know that if you were in the same position the docks would be out for you.” And they hung their heads low and had to agree. Soon the papers, I think the Mirror was first, came out and by Sunday all the major papers had stopped. The secondary picketing and the big campaigns to win support were vital. That is why the Tories had to find this Official Solicitor, who was last used about 900 years ago, to pull their rabbit out of the hat.

Anyway, it was seen as a victory, but it wasn’t really a dockers’ victory, but a victory for the trade union movement.

Now, this glorious chapter in the history of the dockers’ struggle was part of a long and fine history.

Let us quote just a few cases of dockers’ mass spontaneous unofficial strikes in solidarity even with one or two victimised mates.

With all the militant tradition of the docks, however, there has never been any strike that approaches the achievement of the Pentonville stoppage.

Alas, since then there has been a terrible downturn in struggle. Immediately after the Pentonville strike an official strike took place following the rejection of the Aldington-Jones Committee report, which recommended rationalisation.

The official strike went on from 28 July till 18 August, and the dockers got sweet Fanny Adams out of it. On 15 August the TGWU Dock Delegates’ Conference voted 53 to 30 to end the strike and accept the Aldington-Jones recommendations. Most ports voted to resume normal working. However, there was resistance in Hull, and London dockers continued to black depots which had not agreed to take on registered dock workers. Jack Jones reacted by saying, “Unauthorised picketing and blacking is unofficial and must not take place ... Conference decision was binding”. [18]

In the next few months the labour force dropped catastrophically. By 5 February 1973 it was reported that more than 8,000 out of the 10,000 eligible to get redundancy pay, according to the Aldington-Jones agreement, had done so. The size of the dock labour force was cut from 42,000 to 34,000. [19]

The dockers did not give up the defence of their jobs. But the struggle was intermittent. In February-March 1975 a five week long strike took place on this issue in the Port of London. The strike was defeated, and a sense of demoralisation spread all around.

The demoralisation increased, says Bob Light, a docker in the Royal Docks, because the dockers were cheated:

They were assured that the issue would be solved by other means. First of all there was the Jones-Aldington Committee, which took nearly two years to produce its utterly worthless report. Perhaps had the National Port Shop Stewards Committee been in a fit state at the moment they might have been able to rekindle the campaign of 1972. Secondly, the TGWU were going through the motions of promising to come to grips with the problem on a local basis, which was what eventually led to the 1975 strike in London.

The failure of the 1975 strike, particularly the failure to spread it outside London, is one reason why there has been little or no action on the issue since. It left bitterness and demoralisation in its wake. (In fact to this day I am convinced that the strike was masterminded by Transport House to have just that effect!) Another contributory reason why there has been no action since 1972 was the sheer size of the defeat we suffered that year. It not only deflated the movement, it created a lot of bitterness between ports, and it had the effect of collapsing the National Port Shop Stewards for effectively three or four years.

Another spark of activity was the one-day national unofficial strike on 20 March 1977 in support of Preston dockers against the closure of their port. Mickey Fenn writes:

About 23,500 dockers stopped work. Bearing in mind that this represents nearly 85 percent of the total registered labour force, and that the strike was organised by an unofficial committee in the teeth of frantic attempts by the TGWU to undermine it, the strike was an impressive show of solidarity.

In addition small acts of solidarity have occurred again and again. Thus it is the custom to black ships that have been diverted from ports in dispute. But with all said and done, the struggle in the docks in the last few years has been at a very low ebb, and this not only in comparison with the Pentonville days, but even with the general picture of struggles in the 1940s, 50s and 60s.

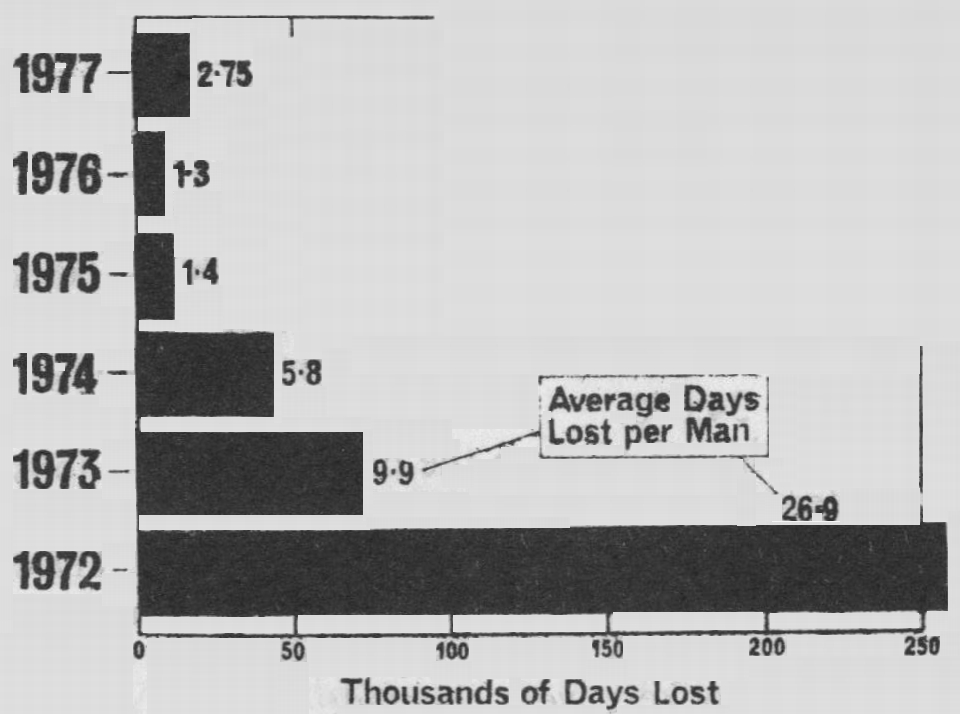

How far the struggle has declined can be seen from the graph on below on strike days per worker in the previously militant Liverpool dock.

|

Engineering employs more than a third of all workers in manufacturing, and traditionally has been one of the strongest bastions of the working class. It has played a pioneering and absolutely central role in shop stewards’ organisation. Let us see if there has been a change in the balance of class forces in the engineering industry in recent years and, if so, in which direction.

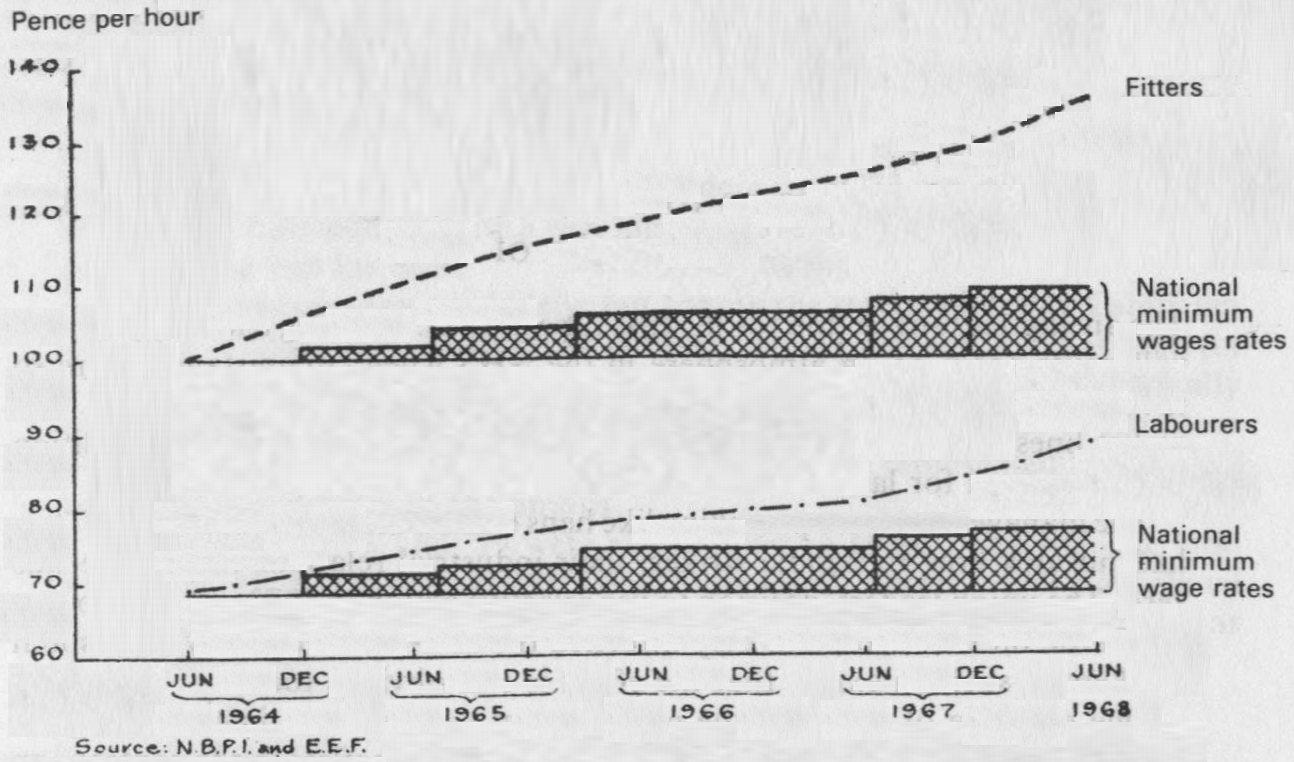

The best measuring rod for shop stewards’ strength in engineering has always been the wage drift.

Engineering workers’ earnings depend on two main factors: firstly, industry-wide bargaining between the national trade union or group of unions and the corresponding employers’ organisation; and, secondly, bargaining within the individual firm. National minimum rates are bargained on the national level; while at the local level negotiation takes place over such matters as piece-work rates and other forms of payment by results, additions to wage rates such as bonuses, and the local rules and practices including manning of machines and demarcation questions. [20]

The difference between the two – the floor and the ceiling earnings – is what wage drift is. Actually the term “wage drift” is a little misleading. It would be better called wage drive, since it is the result of pressure from workers in the better organised industries and firms.

|

ACTUAL EARNINGS OF FITTERS AND LABOURERS IN EEF FIRMS |

|

|

NATIONAL MINIMUM RATE AS PERCENTAGE OF AVERAGE 40-HOUR EARNINGS |

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

Skilled |

Unskilled |

|

December 1970 |

63.6 |

72.9 |

|

November 1975 |

71.4 |

76.2 |

|

February 1976 |

73.0 |

77.6 |

|

April 1978 |

78.7 |

77.9 |

Thus in 1964 the national wage rate was 70.3 percent of a fitter’s actual average earnings (excluding overtime). The national time rate in June 1968 was only some 56 percent of his national average earnings.

Since then, however, more particularly in recent years, wage drift has been considerably squeezed. [22]

The clearest expression of the decline of the wage drift can be seen by looking at the situation in Coventry. A study of some 10,000 skilled workers in 24 engineering firms in the Coventry district showed that between 1953 and 1970 “only one fifth of all increases in ... average piece-work earnings came from national negotiations, while the rest resulted from wage drift”. [23]

Now we find that in this same district there are engineering workers who earn less than the national minimum. Thus a report in May 1979 says that “the Central Arbitration Committee has recently had to award payment of the national minimum rates at firms in the heart of the engineering industry ... it is ... something of a shock to find medium-sized companies with basic wages lower than the national engineering minimum in an area commonly supposed to be very highly paid”. [24]

Under the anarchic capitalist system all sections of the working class do not move in any synchronised way in one direction or another. But with due reservations, we find the general retreat taking place of the last few years affecting practically all sections of the class.

We have no place in this article to give more than a short resumé of one such group of workers – in the hospitals. Many parallels can be drawn with others – particularly white collar public sector workers in the NUT, NALGO and CPSA.

Bill Geddes describes as follows the changes that have taken place since the hospital workers’ strike of 1973:

The ancillaries took action for the first time in 1973. Looking back I think there will never again be an atmosphere in the NHS when circumstances were so favourable for a victory. The sheer enthusiasm of the strikers was fantastic. The picket lines were a riot of fun and laughter, good at the time but a tradition which we paid for later.

The management were panicking like hens when a cat gets into the yard. They had no idea how to handle strikes; their industrial relations experience was zero. The union leaders’ decision to use selective action in 1973 not only lost us the battle on that occasion; they throttled the new-born militancy of hospital workers to such an extent that the effect is still obvious today.

One example of how weak the management were at that time. During the dispute, myself and a few others were handing out leaflets in the canteen, an event unheard of in the hospital before. (We had only set the NUPE branch up a few months previously.) The management saw me handing out the leaflets and the next day I was called into the office and told that I had broken hospital rules. I demanded to see a copy of the rules (I knew there was no such thing). I pretended to be very angry at this attack on my behaviour and walked out, slamming the door behind me.

The next day I got a letter apologising for the accusation over the leaflet incident. I fell off my chair laughing!

In the aftermath of the strike – up to 1975 – the hospital workers still went forward and gained some significant concessions:

During this period, despite the defeat on wages, many hospital branches achieved a great deal in terms of improved working conditions, union facilities, etc. I drew up a shopping list in 1973 and my branch submitted it to the management. Two years later we had won everything on the list.

The victories during this period were often achieved by the threat of action (but at the Hammersmith we used to deliberately involve the members in action even when we knew that talking would be enough). This was a time of great confidence in the better organised hospitals.

[But] after 1975 the tide began to flow the other way. The NHS was reorganised; the most obvious manifestation of this to ancillary workers was a massive influx of bureaucrats ...

The whole atmosphere changed when the cuts loomed up. Management began to feel the whip on their backs and started to go on the offensive.

For the first time shop stewards met resistance when applying for time off, etc. A number of (unsuccessful) attempts were made to discipline myself and other stewards ... Now the crackdown started.

In the years 1977-79:

... the battle of the cuts was lost. All the perks and fiddles which were an unspoken part of the wages in 1973 were taken away whenever possible.

The combination of relatively high manning levels, perks from the past and benefits won in 1973-77 meant that the management had a lot of`slack to take up and the workers had a lot to lose.

Management have now become confident enough to take on the rank and file leaders; my own sacking together with a number of other militants in London has been the latest development in this tendency. The fight to stop the cuts has taken place in the same piecemeal way as the wages campaigns of 1973 and 1979, and the result has been defeat after defeat, resulting in a great deal of demoralisation. Very few of the rank and file leaders from 1973 are still around. This means that in an industry with a very high turnover of staff the experience of the past is being lost for ever.

This may seem very pessimistic but I think the recent Low Pay Campaign reflected this tendency. Despite the hysterics in the press very few hospitals (in London) were involved in real tough action other than the nationally sanctioned days of action. The only action which had the anger to fight to a victory were the ambulancemen and they are badly represented in terms of committees and votes in the unions.

The strikes of 1973 and 1979 were very similar in terms of tactics. The vital ingredient which was missing in 1979 was confidence, despite the fact that council workers were also out. In the hospitals there was an air of pessimism which was not there in 1973.

While the strong battalions of the working class – dockers, miners, shipyard workers and engineers – have been on a low level of struggle in recent years, other groups of workers went into battle: BOC workers, Ford workers, tanker drivers, lorry drivers, firemen, bakers, local journalists, BBC and ITV workers, etc.

BOC workers broke the government guidelines in Phase III, as did Ford workers in Phase IV. Added to these two groups, the lorry drivers have emerged as one of the most powerful groups of organised workers. Their use of the flying picket and “secondary picketing” was fantastic. By and large they got very widespread support from other trade unionists. For example, stewards’ committees in Yorkshire, Lancashire and Scotland organised their own internal checks to turn back goods by hauliers. In Nottingham the NUM agreed to provide full facilities for one picket per pit to turn away non-union drivers. [25]

Even more exciting was the victory of the workers at Perkins Diesel, who won after one week of a very militant occupation – evicting the management and blockading the factory.

The firemen, the bakers and the local journalists entered into battle, fought with great perseverance, but alas, they were either defeated, or at best won very partial victories.

Even amongst Ford workers the feeling at the end of the nine-week strike was far from elation. After all, they could have got 9 percent without a strike, and they were still under penalty clauses, however loose.

It would be a grave mistake to put the success of the workers of Ford, BOC and lorry drivers in the same league as the victory of the miners in 1972 or 1974. The victory of the miners changed the balance of class forces in the country as a whole radically in favour of the working class. The victories of Ford, BOC and the lorry drivers did not. For a Marxist a sense of proportion is central in grasping reality. The heart of the dialectics – this very important if abused concept – is the relations between quantity and quality.

The victory of Ford, lorry drivers, etc. did not overcome the generally great lack of workers’ confidence about their ability to take on the employers and the government.

Never since the Second World War had the real wage of workers declined as much as under the Labour government of 1974–79.

Under the Labour government of 1964–70, notwithstanding the incomes policy, real wages continued to rise, even if slowly [26]:

|

|

|

Average real |

|---|---|---|

|

October 1964–October 1965 |

3.5 |

|

|

October 1965–October 1966 |

0.7 |

|

|

October 1966–October 1967 |

3.7 |

|

|

October 1967–October 1968 |

2.4 |

|

|

October 1968–October 1969 |

3.0 |

|

|

October 1969–April 1970 |

1.7 |

The incomes policy of the Wilson government of 1964–70 only very marginally affected the rise in real wages. Aubrey Jones, chairman of the Prices and Incomes Board, was quite modest in estimating the effect of the policy. He believed that the net effect of the policy had been that the “average annual increase in earnings in recent years may have been just under 1 percent less than otherwise it would have been”. [27]

Under Heath the annual percent change in real income of a male manual worker (married with two children) rose as follows: 1970–71, 2 percent; 1971–72, 7.4 percent; 1972–73, 1. 1 percent – or an average 3.5 percent per year. [28]

Under the 1974–79 Labour government for the first time real wages went down. In the first year (March 1974 to March 1975) they went down by 2 percent; in the second year (March 1975 to March 1976) by 4 percent; in the third (March 1976 to March 1977) by a further 5 percent.

Of course the slashing of wages could not go on. Workers’ resistance had to rise. In the fourth year of the Labour government (March 1977 to March 1978) real wages went up by 5 percent, and in its last year by a further 7 percent. [29]

In March 1979 the real wage of an employed worker was only 1 percent higher than in March 1974. Of course the losses in between were never recovered. Worse than that, the social wage (the quality of the health service, education, etc) was far worse at the end of the Labour government than at its beginning.

If one takes into account the fact that the number of unemployed doubled, it is clear that the real standard of living of the working class as a whole was drastically slashed.

The figures of real wages do not tell the whole story even about the wage changes themselves, as the conditions attached to them are very important. In the last couple of years quite diabolical productivity deals have been dictated by the employers, far nastier than those concluded before, especially those of the first great rush in the years 1966–69.

According to the Department of Employment, at least 1,500 productivity deals were signed between August 1977 and August 1978.

Previously when workers exchanged payment by results for “measured day work” (MDW) they always got a significant wage rise. Not so now. Thus the 2,000 workers of Westland Aircraft were forced to accept MDW accompanied by a wage cut. [30]

We can go on for pages with lists of similar agreements. What is more, in practically all the productivity deals mentioned the rise in wages does not keep up with even the prevailing, let alone the expected, rise in the cost of living.

One has only to compare the Clegg Commission report in 1979 with the 1971 Scamp Commission, on which Clegg served, to see how far back the low paid workers have been pushed. In 1970 local authority manual workers were given a rise of 17.7 percent. [40] Following this award, hospital ancillary workers were awarded 18.2 percent for men and 19.9 percent for women by the Whitley Council. [41] At that time the annual rate of inflation was about 5 to 6 percent.

In 1979 Clegg added rises ranging from 1.7 to 25.8 percent to the original 9 percent given in March. Half the 1.1 million council workers received increases of 4.9 percent or less, and three quarters of the 270,000 ancillary workers 6.5 percent or less. [42] With an annual rate of inflation expected to reach 20 percent it is clear that to the overwhelming majority of local government and hospital ancillaries this meant a wage cut. (No doubt the disgusting attack by Donnett of the GMWU on NUPE did great damage: NUPE, by and large, covers the lowest paid workers, and they came off much worse out of the Clegg report.)

In 1974–75 the low paid public employees’ basic rate was about two thirds of average male earnings. The Clegg report reduces this proportion, so that the conditions of the low paid are far, far worse than in 1974–75 (although they are of course better off than the unemployed).

Heath sacked Clegg (together with Scamp) for his “generosity” to the low paid. It is very doubtful whether Thatcher will do the same. Probably she agrees with the Observer article of 7 August entitled Long Life To The Clegg Quango.

Clegg at the same time meticulously carried out the Tory policy of divide and rule. To a tiny minority of workers (power workers, tanker drivers, ambulancemen, etc) the Tories are ready to give concessions; to the majority of the workers, a kick in the teeth (thus following the secret policy document of Nicholas Ridley, Thatcher’s confidante).

The wages dam has not been broken at all. At best the sluices have been opened for a short time so that some of the water can go through and weaken the pressure.

Naturally the best measure of the balance of class forces and changes in this balance is to be gleaned from the pattern of industrial disputes.

In analysing this pattern some preliminary remarks need to he made. First, the method used by the Department of Employment to publish its statistics of industrial disputes is not helpful. Political strikes are not recorded. Thus the fact that we had more than two dozen political strikes under the Heath government and only a couple since is not registered.

Secondly factory occupations are not registered. Thus the fact that over 200 occupations occurred between 1972 and 1974, and that since then the number declined to less than a dozen, and practically all of these fizzled out after a day or two, is not to be found in government statistics. Even the UCS work-in is not mentioned anywhere in the Department of Employment Gazette!

Thirdly, government statistics speak of “disputes”, thus not distinguishing between strikes and lockouts. Until a couple of years ago it did not matter, as there were hardly any lockouts. But over the last couple of years things changed. And finally, we are not told whether the strikes were offensive or defensive, or whether the workers won or lost.

Without information about all the above facets of the disputes the use of the statistics may easily lead to shallow and unfounded conclusions. Comparing strike days of different disputes as a measurement of the balance of class forces is like gauging the strength of a person solely from their height.

To give an illustration, let us compare the number of strike days in the following national miners’ strikes: 1921, 1926, 1972, 1974. In 1921 72.7 million days were lost, in 1926 146.4 million, in 1972 10.8 million and in 1974 5.6 million. [43]

Even if we take into account that the number of miners in 1972 and 1974 was about a quarter of what it was in 1921 and 1926, still the sheer number of strike days would lead one to the conclusion that the 1921 strike was twice as effective as that of 1972, and four times that of 1974; and the 1926 strike was four times more effective than the 1972 strike, and eight times the 1974 strike. We know of course that it was exactly the opposite.

The categories used by the Department of Employment to define strikes are arbitrary (and subject to change). The system of reporting is haphazard and the DoE’s monitoring depends very largely on the press, and certain key employers filling in forms. These factors alone make the official figures very inadequate for revolutionaries.

The analysis that follows tries to overcome these problems. If it is patchy, it is largely for lack of time to sift the massive amount of material collected and collated by Dave Beecham, to whom we are very grateful. (We shall no doubt find another opportunity to develop it.) He studied just over 1,000 disputes in the two-year period from February 1977 to January 1979.

By and large the disputes were much longer than during the previous period. Of the disputes examined, there were 437 lasting more than two weeks. In many cases they were much longer; not just at Grunwick, Garners or Sandersons, but at Massey-Ferguson (11 weeks), Yardleys (seven weeks), East Midlands Allied Press (24 weeks), Chloride (nine weeks), Lucas, Cammell-Laird, Beechams, Birds Eye, Jones Cranes, etc.

The general picture which emerges is fairly uniform – of greater and greater efforts demanded of workers to maintain the status quo, much more aggression from the employers, small victories won at high prices.

To quote four examples. First, the 11-week strike at Massey-Ferguson in Coventry – won after sit-ins, injunctions and a press witch-hunt – was about management taking 130 men off the clock for “lack of effort” during piece-work negotiations. It was a key dispute for the company, which was trying to bring in a new line of tractor cabs. Subsequently there were three more stoppages on the same issue ... to resolve a question that might have involved a two-hour walkout in the heady days of the late 60s.

Then the case of the Lucas dispute later in the same year. This involved two months on the streets, massive layoffs and a bitter press campaign – at the end of which the toolroom returned having defended the status quo on their bonus and with a bit more money – £3 a week plus a small lump sum.

The third is the case of David Brown. There were three serious disputes there during 1977 – the first an aggressive but lengthy strike in support of combine-wide bargaining, the second also seeing the shopfloor on the offensive, and the third an important staffing dispute which was very quickly lost.

Lastly the case of Marshall Cavendish. There the journalists had a 4½ month long campaign of sanctions to win a rise outside pay policy and then had to go on strike for nine weeks a year later to enforce the commitment they’d won. They got the money and the company got 30 redundancies (out of 120 staff).

Over and over again similar examples crop up. The problems of protracted disputes, or of management picking further quarrels or of exhaustion among the workforce at having to defend an agreement, run right through the period.

To set against this picture are the examples of magnificent solidarity – well known, like the Cricklewood postmen and Grunwick, or very obscure, like the half-day strike call in Swindon in support of the sit-in at Jones Cranes.

A big proportion of the industrial disputes were clearly defensive. There was a large number of disputes about victimisation and/or union recognition. The results do not make happy reading – out of 74 such disputes, 32 were won, 35 were lost and seven were “uncertain”. There were disputes concerned with arguments over staffing, work organisation, operation of new processes, etc – a very large cause of strikes in the period, as management has in some cases systematically tried to encroach on areas “traditionally” left to stewards to sort out. Altogether 316, or nearly a third of the disputes, belonged to this category.

There were in addition 151 token actions, i.e. one-day or two-day stoppages, usually against pay offers in line with government policy.

This is quite a significant total. When added to the number of cases of work-to rule, overtime bans, etc – 157 – it presents a picture of a third of disputes being conducted in a very cautious manner: trying to avoid losing money, fear of the rank and file’s lack of support, employers’ aggression ... These were all factors inhibiting clear and determined displays of militancy in the period.

Of all the disputes 80 were lockouts, a massive rise compared to previous years when the number of lockouts a year could be counted on the fingers of one hand. In many cases, even when the workers did win a victory, it was not unmixed. For example, the long Lucas toolroom strike in mid-1977 was a partial victory, but involved some elements of shopfloor defeat as well. Similarly, the provincial journalists’ strike last winter saw some people getting 25 percent, others 13½ percent – and the dispute ended with serious victimisation, lockouts and rank and file demoralisation.

Throughout the period there are three turning points: one, the firemen’s strike; two, the Ford and lorry drivers’ strikes; and three, the industrial action of 1½ million manual workers in local government and the hospitals.

Following the defeat of the firemen, there was a sharp swing to the defensive over the following months, March, April and May. In the week that Callaghan stood firm and the TUC ditched the firemen there were three lockouts. It was Christmas week. Subsequently the press shop at Ford Halewood lost a decisive five-week battle for shopfloor control. The tanker drivers gave up the ghost on an overtime ban (they lost out again the following year). Workers at Raleigh in Nottingham fought a costly dispute for almost no benefit – a 4½ percent productivity deal.

Then came Ford’s and the lorry drivers’ strikes, and hopes rose for a breakthrough on the wages front. Instead, after the sluices were opened a little they closed sharply on the 1½ million low paid workers in local government and the hospitals.

Throughout the period the picture was much more of a mosaic than in the years before. By and large we find a very contradictory situation. Well organised forces were able to hold out against the odds with unprecedented tactics in some cases. (For instance, the South Wales lorry drivers blockaded railway lines and steel works to win 15 percent without strings. On the other hand, many “traditional” strong groups fell apart rather than take on the employer.)

In conclusion, in recent years: (1) disputes have been far more bitter and lengthy; (2) the employers were far more aggressive and quite often unready to concede anything except after a long battle; (3) lockouts were back with a vengeance; (4) the proportion of disputes ending with workers’ defeats or partial defeats was much greater than in previous years.

Does the growth of union membership over the last few years in any way disprove our conclusions about the change in the balance of class forces in favour of the capitalist class?

Let us first sum up the growth in union membership.

|

TRADE UNION MEMBERSHIP 1970–77 (Millions) [44] |

|

|

|

End of year figures |

|

1970 |

11.187 |

|---|---|

|

1971 |

11.135 |

|

1972 |

11.359 |

|

1973 |

11.456 |

|

1974 |

11.764 |

|

1975 |

12.026 |

|

1976 |

12.386 |

|

1977 |

12.707 |

On the face of it, if growth in trade union membership by itself showed growth in workers’ power vis-à-vis the employer, that power must have grown much faster in 1975–77 than in 1971–74. In the years 1975–77 membership grew by 943,000, or by 314,000 a year, while in the years 1971–74 union membership grew by only 577,000 or 144,000 a year. The shallow conclusion should be: the real years of working class advance were 1975–77, while those of 1971–74 were relatively unimpressive.

As a matter of fact there is quite often an inverse relation between growth of union membership and the strength of shop organisation, as many a management prefers a closed shop as a way of disciplining its workers. Thus a survey of manufacturing companies conducted in 1978 showed that three quarters of the managers preferred the closed shop. [45] Union membership by itself, however much we prefer members to nons, does not immediately and necessarily represent an increase in the strength of the working class.

T. Nichols and H. Benyon emphasised this point in their study of ICI: “The closed shop was enforced ... by an agreement between the company and the union ... Those who were shop stewards at the time welcomed the agreement because it established the union ... and saved them a lot of work. But it also ensured that no widespread, active, recruiting campaign ever took place on site.” As one foreman commented, “After the closed shop was introduced I would say the union collapsed completely”. [46]

Also, the main addition of members to the unions was in white collar areas which lacked a tradition of struggle.

|

THE GROWTH OF WHITE COLLAR AND MANUAL UNIONS, 1948–74 [47] |

|||||

|

|

Union membership in millions |

% increase |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

1948 |

1970 |

1974 |

1948–74 |

1970–74 |

|

White collar |

1.964 |

3.592 |

4.263 |

+ 117.1 |

+ 18.7 |

|

Manual |

7.398 |

7.587 |

7.491 |

+ 0.1 |

− 1.3 |

White collar workers are traditionally far less strike prone than manual workers.

|

NUMBER OF STRIKE DAYS PER 1,000 EMPLOYEES MANUAL AND |

||||||

|

|

1966 to 1968 |

1967 to 1969 |

1968 to 1970 |

1969 to 1971 |

1970 to 1972 |

1971 to 1973 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Manual |

194 |

249 |

380 |

386 |

452 |

419 |

|

Non-manual |

16 |

21 |

46 |

55 |

69 |

49 |

Therefore, it would be very mechanical, not to say banal, to conclude from the growth of union membership that the balance of class forces shifted in favour of the working class.

To understand how far the labour movement has moved to the right, and how far the shop stewards’ organisation has been weakened in recent years, nothing could serve better than to look closely at the campaign round Grunwick.

The stamina, courage and valour of the strikers was outstanding. But what kind of aid did they get from the trade union movement? In terms of size of strike and length of dispute, two previous strikes come to mind: Roberts-Arundel in Stockport (1966–67) and Fine Tubes in Plymouth (1970–73). Both, like Grunwick, were about the refusal of management to recognise the union; both started with the sacking of the strikers and the use of scab labour.

The number of strikers in Grunwick was 137, in Roberts-Arundel 145, and in Fine Tubes 169. Grunwick’s strike went on for nearly two years, Roberts-Arundel for 18 months and Fine Tubes for three years.

It would not be immensely useful to make an analogy between Grunwick and Fine Tubes. Grunwick’s took place in an area with a very high level of trade union organisation existing over many decades. Fine Tubes’ strike took place in Plymouth, probably the area with the weakest trade union organisation in the country. “in the past there has been no tradition of workers’ organisation in the Plymouth area,” writes the historian of the Fine Tubes strike. Even during the General Strike of 1926, the Plymouth dockyards, which employed some 20,000 workers, the great majority local people, went on working. [49]

Stockport, on the other hand, like north London, is an area of strong trade union organisation with a very good tradition.

Roberts-Arundel strikers got aid from fellow trade unionists in the district compared to which the aid given to Grunwick’s strikers – and equally to Desoutters in the same period – by their own district paled into absolute insignificance. As Roberts-Arundel strikers were members of the AUEW, the Stockport district of the union imposed a weekly levy of 6d. In addition, collections were taken repeatedly around the factories in Stockport and Manchester. Many workers from all over Stockport came day and night to man the picket line. A number of all-Stockport strikes took place. Thus on Wednesday 22 February 1967 a half-day token strike took place in Stockport and surrounding areas – 30,000 workers clocked off at lunchtime and many of them went to the Roberts-Arundel factory for a demonstration.

On 1 September, “some 40 factories and building sites in Stockport and surrounding areas stopped work. The police had banned any demonstrations outside the factory, but a meeting was planned to take place behind the factory on some waste ground. About 3,000 workers turned up for this, something like one tenth of those who were on strike for the day.”

On 1 October another all-Stockport strike took place. Once more some 30,000 workers stopped work and a huge demonstration marched through Stockport. A number of very militant and violent demonstrations took place around the factory.

Added to this, very widespread blacking took place. The products of the factory were “subjected to the most painstaking process of blacklisting that surely was ever experienced by any employer in dispute with the unions ... The blacklist began with the names of 245 companies ... By mid-June 1967 there were only 45 names left. The others had been taken off the blacklist.”

The strength of the workers’ organisation was such that even the police had to bend to it. After using violence against pickets both at the factory gates and, worse, at the police station, they were forced to accept that they had acted wrongly. When six pickets were arrested on 22 November 1967 and three of them beaten very badly at the police station the police authorities were forced to apologise, and pay compensation to the injured: “ ... the three victims of police assault were paid agreed damages by the police. Allen got £1,322 for a spinal injury and a broken nose, Heywood £583 for a broken nose and a battered face, Cook £375 for a broken nose, body injuries and subsequent mental anxiety.” [50]

The strike ended in victory. The owner of Roberts-Arundel recognised the AEU after admitting “that the strike cost him £1 million’. (The manager went into bankruptcy and the factory was closed. At least there was no non-union factory in Stockport and the principle of trade unionism had won.)

Now what about Grunwick? All honour to the Cricklewood post workers who blacked Grunwick and only lifted the boycott under the gravest duress from the union leaders. But what did the other workers who live in north London do to help Grunwick strikers?

Ken Montague was one representative of the Grunwick Strike Committee to go round the factories in the Park Royal area:

We were touring factories where in the years 1971–73 I visited many times and was received with great enthusiasm for action, whether for solidarity strikes or collection of money for workers ... We were visiting people we had built up a close relationship with over the intervening years, and this was at the height of the mass picketing, when miners were coming down from Yorkshire to join the picket line. This time we didn’t even try to ask for strike action – all that we hoped for was that mass meetings would be held during work time with invited Grunwick speakers and possibly that the workforce might march down to the picket line perhaps during work time. The only shop stewards committee to comply was at Racal BBC, Wembley, where the convenor was a close contact of the IS, an excellent convenor anyway, who had recently organised the factory and won recognition with a very young and mainly Asian stewards’ committee.

Other than that, the response was one of consternation and timidity. In the established AUEW factories there was a lot of formal sympathy but the argument generally ran that they had “so many problems” of their own at the moment that they didn’t feel they could do very much. This wasn’t just an excuse – many of these stewards and convenors do seem to be exhausted and worn down by problems. Even in some of the more recently organised factories there was a fear of putting too many demands on the membership. Associated Automation was a classic example of this. This was a factory which we had helped to organise, where we had effectively led a strike against redundancies that was 80 percent successful, and which was right between the two Grunwick factories. The convenor, assistant convenor and senior steward are all very friendly (genuinely so) and for a time were intimately involved in the Grunwick strike. Yet here the committee really did not feel it was strong enough to call a factory meeting over the issue. They were ashamed of the fact.

In reality these fears, genuine as they were, seemed to be exaggerated. The mass meeting at Racal, for example, went beyond the convenor’s expectations – there was a half-day strike and 200 workers marched to the Grunwick picket. On the morning of the 2 or 3 July mass picket I talked to workers at the Associated Automation gate opposite the Chapter Road picket. About 40 workers had gathered there and had refused to go into work. Most of them were resentful that a mass meeting had not been called, and in the end about 30 to 40 Associated Automation workers spontaneously walked out to join the picket line – or so I was told. Perhaps this is more of an extreme example than a classic case but it sums up what seems to be a common condition among many local stewards – extreme reluctance to bring “outside” issues into the factory, and an increasing unwillingness to expose themselves to mass meetings. I can remember when mass meetings were called at the drop of a hat – but today it’s like asking for an all-out strike.

One effect of weakening the role of the stewards has been to produce a marked decline in solidarity action, as demonstrated in the readiness or ability to give financial support to workers involved in disputes.

Let us compare two strikes of workers in one and the same union, and one and the same district – the Acton Works, London Transport, strike of 24 September to 20 December 1969, and the Desoutter strike of 13 May to 30 September 1978. The LT strike was about a relatively unimportant issue, a question of grading. Desoutter was on a very important question of principle – recognition.

In both cases the amount of money collected was about the same – just over £13,000. But between 1969 and 1978 wages had risen about three times, so that the amount collected for Desoutter’s was only about a third of the amount collected in real terms in 1969.

More important were the sources of the money. LT Acton got £3,198 from a levy imposed by the North London district of the AEF and £500 from a levy in South London district. Desoutter did not get a penny from a district levy, as the district committee refused to impose one.

In addition LT Acton received regular weekly amounts of money based on factory levies from at least seven big workplaces in addition to the district levy, while only four places collected regularly for Desoutter and none were on a weekly levy.

Roger Cox had the following comment to make on the above facts:

The question of levies is central. The real difference between 1969 and the summer of 1978, I believe, is not the amounts of money but the inability of stewards in the factories to call a mass meeting and win support for a levy. I think it is here that we face a real problem, because it shows the distance between the shopfloor and the leading stewards. It also shows the total lack of confidence in the rank and file by the leaders. Also I suspect that the stewards no longer want to disturb the members in case they lose.

The level of financial support for Desoutter is poor compared to that of Acton Works. It would pale even more if compared with, let us say, the Marriott strike of 1963. This, like Desoutter, consisted mostly of black workers and was also on the question of recognition. Marriott workers collected £9,500. At that time wages were a fifth of those in 1978. So if we use the same measure of money in real terms, the collection for Desoutter was only a quarter of that for Marriott.

If one looks at a star factory like ENV, that was always ready to raise money in support of workers in struggle, it is clear how far we have been pushed back. The 1,100 workers at ENV collected £1,500 during the 13-week strike at British Light Steel Pressings in Acton in 1961. For the Marriott strike ENV collected £1,717. [51] Basically the decline in the levies for strikes reflects the erosion of traditional solidarity, and the decline of a basic socialist attitude that was the inheritance of our movement. To rebuild this tradition again one has to persevere, and one must put the politics of class solidarity to the fore.

Analysis of the industrial disputes over the last few years shows the employers in a much more belligerent mood. As an expression of their stance a document published on 19 March 1979 by the Engineering Employers’ Federation, entitled Guidelines on Collective Bargaining and Response to Industrial Action, is most illuminating. [52]

The origins of the guidelines go back some months. Several major firms, and GKN in particular, threatened to quit the EEF if it did not produce a policy which would enable management to fight stewards’ organisation and involve right wing AUEW officials in stamping out militancy. GKN was not alone. Hardline companies, like Westland Aircraft, Serck, Birmid Qualcast, Johnson Matthey, Powell Duffryn, Edgar Allen, Low and Bonar, have all been exerting their influence to get a tough line agreed in the EEF. Not surprisingly, these are the same companies that always impose lockouts (five in March–April 1979 in South Wales alone). They are the same companies that fund blacklisting organisations like the Economic League, and many of them supply members of the Economic League Central Council. [53]

The change in the actual balance of class forces between the working class and the capitalist class, between the heyday of the struggles of 1969–74 and the last couple of years, shows itself in the paradoxical situation that while the Tory Industrial Relations Act existed the employers resorted to the courts against workers far less than they have done in the last couple of years.

A book dealing specifically with the actual working of the Industrial Relations Act has this to say:

Managers ... combined effectively with unions to draw the sting from the law’s attack on the closed shops ... they believe the use of the law could only make disputes more intractable. Managers were aware that legally enforceable agreements, attempts to end the closed shop, and restriction on the right to take industrial action were strongly opposed by unions and their members. [54]

Thus throughout the two and a half years of the Industrial Relations Act there were only four applications to the National Industrial Relations Court against the closed shop. [55]

In one case, when a worker named Joseph Langston insisted on his right to work in Chrysler Ryton factory, Coventry, and by law he had the right not to belong to the union, he won his case at the Birmingham tribunal (28 December 1972).

The next day Langston went to Ryton and was met by “shouting, jeering and swearing workers who had staged a lightning walkout in protest”. Langston was sent home, still on full pay, and arrangements were made to send his wages to him to avoid further confrontation. [56]

Later Chrysler dismissed Langston. Managements connived at getting round the law by including in collective agreements they signed with the unions a disclaimer of any legal binding of the agreements. And the reasons were obvious. Management were frightened of shopfloor reaction: “Managers recognised that legally binding agreements would not necessarily have been easier to enforce than those binding in honour only”. [57]

Altogether:

There were 33 applications by firms to the NIRC seeking relief from industrial action (there were also four applications by employee organisations against unions seeking similar relief). Obviously these represent only a very small minority of all disputes. For example, in 1971 there were 2,228 stoppages, in 1972 2,497 and in 1973 2,854 stoppages. (these figures also show that despite the Industrial Relations Act the number of strikes continued to increase.) They no doubt underestimate the actual number of stoppages and in addition to those recorded there are various forms of industrial action which are not notified for statistical purposes. The direct use of the Industrial Relations Act in situations of industrial action was extremely rare. [58]

The companies that applied to the NIRC were untypical in their industrial composition: “The pattern presented is of a use of the act by a small number of firms in private sector service industries”. [59]

The NIRC itself was quite careful not to come too often and openly on the side of the employers: “Less than half the employers who sought orders of the NIRC got them”. [60]

The government itself quite early got cold feet about the law: “Some managers told us that the DoE had actively discouraged any use of the act’s collective bargaining provisions”. [61]

Where the law did intervene with a heavy hand – the docks and Shrewsbury – in the first case it had to beat a hasty retreat; in the second, because of the betrayal of the union leaders and the weakness of workplace organisation, it was as vicious as it could be. Building workers in North Wales are not in big well organised units, as were the five dockers who landed in Pentonville jail. Hence Des Warren served three years in prison, Ricky Tomlinson two, and Ken Jones nine months. The law used against the Shrewsbury workers was not the Industrial Relations Act but the criminal law regarding “conspiracy”.

The government tried to use the law against the railwaymen (May–June 1972), but they were very inept. A cooling-off period was imposed, and then a ballot of the workers involved. The results of the ballot showed a better than six to one majority in favour of the union rejection of BR’s last offer, and the Sunday Times’s comment on this was typical of press reaction: “It would seem that the ballot which was intended to cool off the crisis has only served to do the opposite”. [62]

All the above shows clearly the actual strength of workers’ organisation at the time.

Now let us look at the activities of the court, and police, in industrial disputes over the last couple of years. We need only give a few examples from the courts, and these especially from the Court of Appeal presided over by Lord Denning.

On 29 July 1977 the Court of Appeal sided with George Ward of Grunwick by overruling a High Court decision in favour of ACAS.

On 20 May 1977 the Court of Appeal decided that the Association of Broadcasting Staffs had no right to refuse to transmit the 1977 BBC Cup Final to South Africa. The court ruled that this was not a trades dispute, but “coercive interference”.

In the same year Lord Denning came down heavily on SOGAT. The journalists of the Daily Mirror went on strike and so stopped the production of the paper. The Daily Express decided to take advantage of the situation and increased its output by 750,000 copies. The general secretary of SOGAT, Bill Keys, whose members handle the distribution of newsprint, instructed them not to handle the extra copies. The Express applied for an injunction to restrain SOGAT. The Express lost in the High Court, but then won in the Court of Appeal, which found that there was no dispute between SOGAT and the Express.

The case of Star Sea Transport of Monrovia versus Slater, secretary of the National Union of Seamen, had even more serious implications. The International Transport Federation tried to secure that the wage rates paid to Greek and Indian sailors on a Liberian-registered vessel – the Cammilla M – were in line with recognised ITF minima, but the employers won an injunction when the unions tried to prevent the ship sailing from Glasgow. The judges said it was an open question whether the action was a trade dispute.

Then just before Christmas 1978 came the case of Express Newspapers versus McShane and Ashton. This arose out of a strike called by the National Union of Journalists against provincial newspapers. Because the local papers also get news copy from the Press Association, the union called upon its members employed in the Press Association to come out on strike as well. About half of the PA did not obey the union instruction. The NUJ then ordered its members employed by the national newspapers to black PA copy. The Express sought an injunction against the NUJ officials McShane and Ashton. The High Court granted the appeal, and when the NUJ appealed to the Court of Appeal, their case was dismissed. Lord Denning held that the blacking of PA was not in furtherance of a trade dispute. It seems no act of solidarity is in furtherance of a trade dispute.

Then again the case of United Biscuits versus Fell. This case arose out of the lorry drivers’ dispute. Fell, a lorry driver, was running the picket line at Loders and Nucoline, one of the sources of supply of edible oil for United Biscuits. The High Court declared that, as the lorry drivers’ strike was not against United Biscuits, to allow this “secondary picketing” would be tantamount to “writing a recipe for anarchy”. [63]

When the Nottingham Evening Post refused to recognise the NUJ and NGA, the NGA wrote to all concerns regularly advertising in the paper asking them to stop advertising. Sixteen organisations continued to advertise, and at the end of February 1979 they were informed in a joint letter from NGA and SLADE that all members of these two unions on any newspapers or periodicals would be instructed not to handle any advertising submitted by the relevant organisations. Some 26 organisations sought an injunction against Wade, the NGA general secretary, and others. The High Court granted an interim injunction, and when the NGA appealed against this the Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal. Lord Denning made it clear that this was a case of secondary industrial action. [64]

The legal costs to the NGA were as high as £84,000 – higher than the fines imposed on the TGWU by the NIRC in 1972 which (like those imposed on the AEU) had been reimbursed to the TGWU.

On 19 July 1979 Lord Denning and the Appeal Court decided that the strike by the 8,000 low paid provincial journalists last winter was unconstitutional. This interpretation of the NUJ Rule Book means that members who scabbed through the strike and then benefited from hard won gains could not be disciplined.

Leicester Mercury journalists were banned from blacking a news agency which supplied copy to the Nottingham Evening Post.

NUJ members at the Stratford Express on strike in defence of their closed shop were sued for libel over a leaflet they produced. More writs have been threatened to stop the NGA from blacking the Express.

In north London two NUJ members at the Camden and Hornsey Journal were taken to court by a sub-editor who resigned from the union. [65]

At the time of writing there are a few further cases of courts persecuting trade unionists – for instance, the High Court injunction secured by Wandsworth council against UCATT official Lou Lewis, preventing him picketing in defence of direct labour.

In recent years the courts have been joined with great vigour by the police in cutting down the power of pickets. Besides Grunwick, there are many other cases. The most recent is the case of Andy Darby. He is a GMWU senior steward arrested on 5 February on an unofficial picket line outside the GLC refuse tip in Factory Lane, Croydon. That morning the police had repeatedly tried to stop pickets talking to the lorry drivers coming into the tip. When the police waved on a 32-ton crane lorry Andy stood in front of it and threw a door down in its path. For this he got three months imprisonment for “threatening behaviour”. [66]

In practical, technical terms, present laws and their application are tough enough to satisfy the needs of the employers. The new proposed Tory industrial relations act has mainly ideological importance, to justify the policy, to win the battle of people’s minds, to give succour to the police in their breaking of strikes.

The change in the balance of class forces in Britain has been caused by a whole number of inter-related factors: incomes policy; the massive establishment of productivity deals which has been associated with the weakening of the independence of convenors and shop stewards; the wide spread of workers’ participation in industry; the move to the right of “left” trade union leaders like Jones and Scanlon; the integration of convenors into the trade union structure; the role of the Communist Party as the main organiser of rank and file activists in industry, both in supporting workers’ participation and in supporting the left union officials; the ideological trap of the concept of “profitability”, “viability”, etc, combined with a loyalty to Labour even when Labour attacked workers’ living standards; the impact of the economic crisis – cuts, sackings, etc, etc, on all the above factors.

The single most important factor in the deterioration of shopfloor organisation has been the weakening of stewards’ bargaining position and role during the period of freeze and incomes policy. In fact it does not make much difference to the power of the shop steward whether incomes policy is of nil growth, 3½ percent, £1 plus 4 percent, £6, 10 percent, or 5 percent. As a matter of fact only three of the last 13 years have had no incomes policy.

A more insidious and in the long term damaging effect on shopfloor organisation has been the move towards productivity deals. Our organisation was far ahead of everybody else in recognising this trend. Ten years ago the book The Employers’ Offensive, subtitled Productivity Deals and How to Fight Them, highlighted the ruling class determination to stop wage drift and transform shopfloor relations by removing stewards from effective direct influence on take-home pay, thus weakening the support they had from their constituents.

The Donovan Report on trade unions argued that the abolition of piece-work would undermine the autonomy of shop stewards and would help the unions to integrate the stewards into the union machine, so that they might better control their activities in the interests of managerial order. The main target was clear – the factory floor organisation.

The aim of the Donovan Report was the integration of the shop stewards into a streamlined union machine, into a plant consensus. This process of integration could be helped by greater legal and managerial discipline. Order had also to be brought into the working of the unions: “Certain features of trade union structure and government have helped to inflate the power of work-groups and shop stewards.”

Among the institutional changes proposed by the Donovan Commission was, first of all, the substitution of factory agreements for industry-wide agreements. [67] The negotiation of piece-rates makes for permanent activity in the shop and hence for very close relations between the shop steward and the workers he or she represents.

The elimination of piece-working, especially if it is connected with the transference of bargaining to a company-wide level, necessarily takes away the power of shop stewards to seriously affect the wage packets of the workers they represent. This applies to all industries from engineering to the docks to the mines. The shop stewards become integrated into the union machine and incorporated into management.

A study of actual working of the union at shopfloor level in the mining industry has this to say: “At one time the pay structure and methods of domestic bargaining in coalmining had much in common with those in engineering – industry agreements on pay settled minimum rates, leaving ample scope for domestic bargaining in the collieries.”

Things changed radically in 1966, however, when a national agreement on wages – NPLA – was introduced:

The delegate continued to agree work terms with management, but this became something of a routine. He argued the case of men who wanted to be regraded to a higher rate of pay, or moved to another job or shift; dealt with disciplinary cases; investigated accidents; checked on safety, dust and lighting; advised the injured and the sick on their entitlements; and helped his members with domestic problems – housing, debts, divorce and so on ... The delegate’s job had thus become largely administrative.

In an interview, Pete Exley, surface fitter at Grimethorpe Colliery near Barnsley, described the work of the four full timers in his colliery – the president, treasurer, secretary and delegate: “The treasurer’s main job is on a Friday, like today, to dish out money for bereavements, old age pensioners. We still have that thing in Yorkshire that we pay so much a fortnight out of the branch funds and you have the old retired miners coming for this money.” The president does “the same. He is just there for any disputes and negotiates and hangs round in the union box. You see them coming in at 9 o’clock every day. They are gone by about 1.30 or 2 and are in the union box for most of the rest of the time. If there is a dispute down the pit or safety checks or something like that they will go down the pit and do that.”

To blunt the edge of shop steward organisation, Devlin Phase II introduced a clever design to divide one port from another. Eddie Prevost writes:

In different ports there are differences in hours of work, manning, pay. Now negotiations take place at a local level. The national agreement covers only a small proportion of workers’ wages and conditions ... The main weakness for us was the differences between the ports over the time they negotiate their separate agreements.

“Today the TGWU strategy”, writes Bob Light, “is to absorb militancy through the safer channels of officially-recognised shop stewards”:

As far as the employers are concerned, they too now try more to contain militants into official channels rather than victimise them ... The shop steward’s job can be very easy. There is no supervision by management at all, so there are no hassles about things like timekeeping, etc. A steward could almost come in when he liked and go home when he liked. And some do! We are provided with an office by the employer, and if you liked you could sit in there all day just talking, reading, playing cards, drinking tea – whatever you liked. So there’s no doubt at all that shop stewards can have it very easy if they like, and the truth is that many of them do like it.

And Eddie Prevost adds, “Shop stewards in the Royal work two weeks as a steward and two weeks on the job (in theory). Sickness and holidays mean in practice they don’t work that much. In other docks stewards are full time.”

One result of the weakening of dockers’ shopfloor organisation has been the practical disappearance of the famous mass meetings. Eddie Prevost writes, “Since the 1975 strike in London dock gate meetings have been very poorly attended. No doubt the government’s pay policy has effectively stifled the shop stewards committees in all docks.”

The power of the shop stewards to negotiate wage rates has been undermined by productivity deals, and especially by transferring bargaining to plant, or worse, company level.

When collective bargaining takes place at a level above the shop, or above the individual plant, the actions of the negotiators which are of primary concern to the lay members are remote from their control. Hence apathy is quite natural. Now with productivity deal negotiations concluded far away from the shopfloor, the shop steward finds himself more and more isolated in practice from his mates, the convenor even more so.

Lord Acton coined the aphorism, “Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” In fact, it would be even more apt to say, “Power corrupts, but lack of power corrupts absolutely.” The decline of the power of the shop stewards in gaining significant wage rises in recent years again and again led to their alienation from their base, to a loss of confidence of the rank and file in the shop stewards, and to a loss of self-confidence by the shop steward.

As against the tradition of shop stewards’ organisation, there is another tradition in the labour movement – that of passive democracy, at best a periodic opportunity to elect the officials. Such a democracy, like bourgeois parliamentary democracy, must lead to general alienation of the officials from the base, and the general apathy of the latter.

Ken Montague describes very well the impact on shop stewards and convenors in engineering factories in north London – the weakening of the ability of shop stewards to affect wages makes them:

... feel that they have no control of their situation any more. In almost every case they are reacting to situations rather than setting the pace for the management. The whole struggle has become a defensive battle and I doubt very much if any but one or two committees in the area have any kind of perspective for actually gaining anything. There is no real sense of there being a purpose or a future in what they are doing. They are distinctly not building very much up, but hanging on. Perhaps the only exceptions to this are where there is the possibility of building something on a combine or network basis (Racal, British Rail, Smiths Computer workers).