First Published: Theoretical Review No. 15, March-April 1980

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The tragic and untimely death of Nicos Poulantzas in Paris last October has meant a great loss to the workers movement around the world, as his life was dedicated both theoretically and practically to the class struggles of the proletariat. As yet, a full assessment of the crucial theoretical interventions initiated by Poulantzas has not occurred. But the importance of his work makes such an assessment a necessity.

Although Poulantzas’ theoretical achievements covered a wide range of issues in Marxist theory, the analysis of the capitalist state always remained central, and it is upon this part of his work that attention will be focused. The inquiry below seeks to show that this work can not be adequately understood apart from an understanding of the works of Marx and in particular the discourse of Capital which provides the grounding which Poulantzas seems to lack only upon a cursory reading. Indeed, this was his project from the start, the elaboration and extension of Historical Materialism, for which Marx had only laid the “cornerstones” (Lenin). Much misunderstanding has surrounded the work of Poulantzas and the now famous charges of formalism and functionalism, not that these tendencies are completely absent, are at least partially explained by a lack of willingness to consider Poulantzas’ work and Marxist theory as a whole. In this essay a few lines of inquiry toward a more complete understanding will be indicated.

No society ever existed without production, without the material satisfaction of the biological needs of its members; and, as Marx noted, “Every child knows that a society which did not reproduce the conditions of production at the same time as it produced would not last a year.”[1] In these words Marx repeats the premise established in the Introduction to a Critique of Political Economy (1857) that the starting point for a theoretical science of social–indeed, even of individual–activity is production. Clearly, from this introduction, production governs consumption and distribution and not the reverse. Similarly, in another passage Marx designates production “the hidden basis of the entire social structure” (Capital, Vol. III, p. 791)

The theoretical starting point for an understanding of production is the labour process, which entails the forces of production; the transformations that human activity inflicts on natural materials (by the use of instruments of production) in order to make use-values,

The elementary factors of the labour-process are 1, the personal activity of man, i.e., work itself, 2, the subject of that work, and 3, its instruments.[2]

and the relations of production, within whose determination the labour process is executed. Marx distinguishes the concept of relations of production (ibid, Vol. I, Ch. VII), the assigners and distributors of agents into objective places in material production, from “production in general,” and this discerning and distinguishing of the relations of production constitutes Marx’s theoretical break with the classical conceptions of production. Specifically, the relations of production distribute agents among two coordinates at the economic level: 1. The property relation, the assigning of uses to the inputs and outputs of production, and 2. The relation of appropriation, the direction and control of the labour process.

The labour process, turned into the process by which the capitalist consumes labour-power, exhibits two characteristic phenomena. First, the labourer works under the control of the capitalist to whom his labour belongs.... Secondly, the product is the property of the capitalist and not that of the labourer, its immediate producer.[3]

Thus, in capitalist production the owners and controllers of the means of production–the objects and instruments of labour–engage the non-owners and non-controllers in transformation of objects of labour into products as commodities. These products are not only use-values but, simultaneously, values embodying surplus value; values which are non use-values for their owners and, thus, necessitating structures and systems of exchange. The result: The capitalist mode of production is divided into two classes, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, each possessing their own objective interests directly opposed to one another. That is, the bourgeoisie seeks (at the economic, political, and ideological levels) to maintain positions of dominance while the proletariat struggles to transform and overthrow their positions of subordination, oppression, and exploitation.

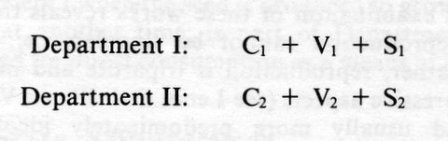

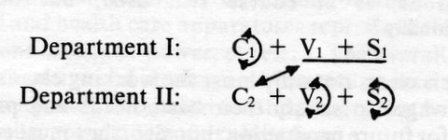

As Poulantzas states, if reproduction is the ultimate “condition” of ongoing production, it follows that every social formation contains a determinant level where the reproduction of these forces and relations of production occur. Posing the problem in this way reveals the critical importance of Chapters XX and XXI of Volume II of Capital. In these chapters Marx demonstrates how capitalist reproduction is based on both the distinction and coordination between two “departments” of capital: Department I devoted to the production of commodities which enter into consumption for production, (that is, capital goods or the means of production) and Department II devoted to the production of consumption goods, (means of subsistence for labour and luxury goods). The two departments are illustrated as follows, where C is constant capital (means of production), V is variable capital (wages paid to labour-power), and S is surplus value (loosely speaking, profit):

Given the assumption that all surplus value is consumed (directly or by means of exchange), and constant capital is reproduced and productively consumed as circulating capital (directly or by means of exchange), reproduction (or more precisely “simple production” occurs by 1. The continued output on an extended scale by both departments, and 2. the interdepartmental trade of numerical value equivalents:

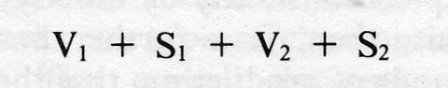

Department I produces constant capital for both Department I and Department II equal in value to Ci + C2. Department II in turn, produces articles of consumption for departments equal to:

Thus, reproduction is able to continue smoothly without accumulation.

But this does not answer all the questions. The introduction of fixed capital, that is, means of production which retain their usefulness for a number of years, radically changes the non-problematic nature of simple reproduction. Structural dislocations are established which are only resolvable by reproduction on an extended scale. Fixed capital wears out in both departments at varying rates depending on the period of the retention of productive use-value. Money funds, simultaneously and necessarily, must accumulate for the ultimate purchase of replacement. However, production in Department I can not vary in sequence with the useful periods of fixed capital. Production can never be discrete, sharply curtailed one moment and suddenly expanded another. Thus, Department I requires a constantly expanding Department II, the constant new creation of exchange networks for the annually produced fixed capital of Department I. In turn, Department I must sustain growth for the provision of an ever expanding Department II via increasing wages (variable capital) for workers with the surplus accruing to capitalists. The curtailment of growth in either department is the necessary and sufficient condition for an overproduction (that is, the existence of commodities without an outlet, values and use-values without exchange value)... “the market must... be continually extended.”[4] And so, “It is the requirement of the capitalist mode of production that the number of wage workers should increase absolutely, in spite of its relative decrease.”[5]

Thus, the presentation by Marx of capitalist reproduction at the economic level provides the grounding necessary for a understanding of Poulantzas’ project by establishing the necessity of accumulation on an extended scale, expansion and growth, for continued reproduction.

The accumulation process, a necessary part of a capitalist economy carries with it profound ramifications for class relations. On the one hand it has effects which tend to deunify and isolate the proletariat, while in turn it also has unifying effects creating conditions for natural cohesion of the proletariat. Marx tells us that accumulation carries both types of ramifications.[6]

In Capital Vol. I, Ch. XXXII, “Historical Tendency of Accumulation,” the division of labour and the socialization of labour, which depicts processes increasing the intensity of labor, increase the unification and organization of the proletariat, and, thus, increase their class power, (i.e., the capacity to fulfill proletarian class interests is intensified). A simple deduction from this fact is, as Marx indicates, the forcast that the “expropriation of a few usurpers by the mass of the people” is, sooner or later, bound to occur; expropriation will take place by a unified and socialized working class if the disorganizing and isolating factors which affect the proletariat are held constant or relatively overpowered:

Along with the constantly diminishing number of magnates of capital, who usurp and monopolise all advantages of this process of transformation, grows the mass of misery, oppression, slavery, degradation, exploitation; but with this too grows the revolt of the working class, a class always increasing in numbers, and disciplined, united, organized by the very mechanisms of the process of capitalist production itself.[7]

Thus, increasing numbers, discipline, unity, and organization of the proletariat, results of the “deepening: and widening” of capitalist production at the economic level, escalate the worker’s ability to fulfill proletarian interests in class struggle.

On the other hand, a further structural result of accumulation is revealed in Capital Vol. I, Ch. XXV, “The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation”; the increasing redundancy of labour and the forming of a reserve army of labour thrown into unemployment. The division of the proletariat into two great camps, the “active sector” (employed) and “reserve sector” (unemployed), not only works to depress the wages of the active sector because of competition for jobs, but also deunifies the proletariat, thus constituting a counter-tendency of accumulation fostering capitalist class stability and hegemony:

The industrial reserve army, during periods of stagnation and average prosperity, weighs down the active labour army, during periods of overproduction . . . it holds its pretensions in check.[8]

The over-work of the employed part of the working class swells the ranks of the reserve, whilst conversely, the greater pressure that the latter by its competition exerts on the former, forces these to submit to overwork and to subjugation under the dictates of capital.[9]

Technological development, the concentration and centralization of capital, results in further structural stratifications of the working class. For example:

1.) Cleavages often exist between the working class in the sectors producing highly technical fixed capital and other industrial sectors. The expansion of jobs in the former sectors results in lay-offs and job obsolescence in the latter. On the other hand, boycotts of labour saving fixed capital, that is struggles over mechanization in other industries, result in layoffs in the fixed capital producing sectors. Thus, working class cohesion and unity must be achieved and displaced to the political level.

2.) The existence of large highly technical and diversified firms opens places for directive, coordinating labour– labour which is, nevertheless, subjected to capitalist exploitation. When filled, these positions stratify the working class according to the ideological criteria of “mental labour/manual labour.”

3.) Insufficient centralization, fluctuating markets, and certain types of political and ideological intervention in the economy work to reproduce non-monopoly sectors of capital. Relative to the monopoly sector workers, workers in the non-monopoly sectors labour under harsh conditions: less work safety precautions, less paid labour time and less job security. These places are filled by the latent working class population, redundant workers forced from former trades through job obsolescence, minorities and women. Thus, further stratifications of the proletariat are created along occupational (“poor white trash”), racist and sexist lines.

Taken by itself the exposition of the conditions of reproduction in Volume II of Capital simply offers arithmetic proportions for stable capitalist growth. Given sufficient data, levels of accumulation are calculable. But this arithmetic articulation of economic reproduction cannot be taken as a completed theory, thereby allowing the “conditions” for reproduction of labour power and, thus, the relations of production themselves to be ignored:

The capitalist production process, therefore, considered in its interconnection or as reproduction, produces not only surplus-value, but it also produces and eternalizes the social relations between the capitalist and the wage-earner.[10]

The lacuna, the gap, in the theoretical unity of the theory of reproduction in the capitalist mode of production can be filled only when those so-called “historical” chapters of Capital (Vol. I, Ch. X, “The Working Day,” Ch. XV, “Machinery and Modern Industry,” Ch. XXV, Sec. 5, “General Law of Capital Accumulation”) and Marx’s political works are investigated and incorporated in the analysis. An examination of these works reveals that the theory of reproduction cannot be singular, i.e. purely economic; rather, reproduction is tripartite and includes political/ repressive aspects (see Lenin Col. Works Vol. 29, p. 470) and usually more predominately ideological determinants:

It is not enough that the conditions of labour are concentrated in a mass, in the shape of capital, at the one pole of society, while at the other are grouped masses of men, who have nothing to sell but their labour-power… The advance of capitalist production develops a working class, which by education, tradition, habit, looks upon the conditions of that mode of production as self evident laws of nature. . . . Direct force, outside economic conditions, is of course still used, but only exceptionally.[11]

This much is clear, not only must the working class receive sufficient wages to satisfy their basic needs and produce off-spring for future production, but also, they must come to work sufficiently submissive, dominated, isolated, and privatized in order to accept their conditions of exploitation. Necessarily a social cohesion between objectively opposed classes must exist so that production is not interrupted constantly by bloody warfare between the classes. This, then, is a further basic postulate of the capitalist mode of production, that the reproduction of the mode of production is comprised of particular ideological and political apparatuses which operate to counteract the disruptive tendencies of accumulation and to insure cohesion and stability within the system. Here, Poulantzas’ project of the construction of a “regional theory” is crucial for the completeness of Marxist theory. And as he defines those political and ideological apparatuses possessing this mode and whose existence has been established, they are covered by the concept of the state. To be clear, Poulantzas does not define the state as a self evident empirical object, i.e., as an all encompassing object to be simply observed and analyzed; instead he presents theoretical postulates, elaborations of Marx’s own work to be identified, elaborated, or proved untenable, just as the primacy of production is subject to these same processes. In fact, these postulates are the necessary theoretical ground for a empirical analysis. That is, empirical analysis can not look at “this institution” or “that institution” over time in order to reveal the inner mechanisms of the capitalist mode of production.

The existence of a state apparatus (either repressive or ideological) does not depend on its legal or nominal status (for example, government = state), but on the contrary, the place and significance it holds within the entire structure of social relations. Thus, unlike functionalism, (of which Poulantzas is often accused) an empirical analysis based on his work must be developed and grounded on theoretical, non-empirical conceptions. An institution over time may or may not be a state apparatus depending on the presence or absence of unifying social operations with respect to reproduction, which in turn depends upon relations and relative strengths of the class forces which are embodied and struggle within a particular apparatus. This, for Marx, is not a novel or contradictory procedure; the same is true of his explicit analysis of the economic level. For example, production of seed which may be at one time part of Department I when the seed is produced to grow and renew crops, at another time, is part of Department II when produced for direct consumption as a means of subsistence.

Political and ideological apparatuses are, for Poulantzas, class practices, repeated over time and eventually “institutionalized.” That is, they are formally recognized and contained, and provide “conditions” for reproduction. The numbers and variables of apparatuses vary with the diversity and complexity of the social formation. For example, educational apparatuses reproduce the “educational” or “technical” conditions of labour power, the medical and health care apparatuses reproduce the physical conditions of labour power, et cetera. The overall tendency of the repressive and ideological apparatuses is to reproduce the disunity and submission to “the powers that be” (Marx), and passive acceptance of exploitation.

Further, following from the necessary participation and recruitment of the proletariat into these structured practices, the apparatuses become sites, as does the labor process, of oppositions and class struggle. Each apparatus, as a site of class struggle contains a particular relation of class forces which marks the type of class operations the apparatus performs. The overall domination of the bourgeoisie assures apparatuses which serve their class interests, by providing national cohesion under bourgeois domination. The winning and transformation of an apparatus to serve and further develop proletarian class interests, initiates a real or potential “dual power” and as such, the apparatus is no longer part of the capitalist state.

What the capitalist state apparatuses present as a whole is not a share-out of power among classes, but a unity comprised of at least one dominant apparatus maintaining bourgeois hegemony. Moreover apparatuses overlap in a complex system of operations, rules and regulations. The bourgeoisie are not the sole occupants of these state apparatuses, as class relations are reflected in the ordering of those apparatuses in decision making. This ordering is not direct or explicit, but occurs through the changes in areas of jurisdiction, check-ups, information processing, types of personnel, etc. These jurisdictions, etc., transform themselves in responses to transformations in the relations of class struggle as they in turn effect these relations in a sort of feedback manner. That’s why Poulantzas continually refers to the state as a condensation of class forces.

Further, that various apparatuses can be sites of power for oppressed classes also reflects the tendency of the entire ensemble or arrangement of the power sites to unify all the classes and class fractions, to operate as the cohesive factor insuring the class interests of the dominant fraction. Thus, the more an apparatus becomes a decohesifier and enters into the domain of working class organization and power, the more the former operations and scope are taken over and offset by other apparatuses. This is clearly the significance behind recent measures which override local governments tending to serve proletarian interests via county executives, regional tax areas, et cetera. Such measures are always signs of the shifts in class struggle and the ensuing realignments to maintain and preserve national unity between the state apparatuses. Similarly, a threat by the proletariat can also induce repressive responses by other apparatuses. This is evidenced by recent rulings concerning “reverse discrimination,” that is, measures taken by the judicial apparatuses overriding victories of oppressed minorities in the educational apparatuses.

If there is one thesis put forward most forcefully by Poulantzas it is that the state apparatuses tend to organize and unify the dominant classes of a capitalist social formation, while in turn they tend to deunify the exploited and oppressed classes.

A lot of misconception has surrounded this claim. What Poulantzas is not saying is that the state performs these functions because they are necessary for social reproduction in an a-priori manner. But instead what is put forth is the postulation of the existence of a tendency within a capitalist social formation, through concrete and specific “trials and errors” where state operations are subjected to real modifications by the class struggle (in which certain classes are dominant and others subordinate) for the state to act in ways which will compromise and organize the dominant class and effectively deorganize the dominated classes. Some background is necessary for a full understanding of the argument.

The phases of capitalist commodity production (characterized simply: M–C . . . P–C1–M) simultaneously provide a homogeneity and interdependence of the capitalist class as recipients of surplus value produced by exploited classes and a heterogeneity of capital, the division into class fractions: industrial capital, commercial capital, and banking capital... the division into class fractions: industrial capital, commercial capital, and banking capital. . .

The existence of capital as commodity capital (commercial capital) .. . forms a phase in the production process of industrial capital, hence in its process of production as a whole . . . these are two different and separate forms of existence of the same capital.[12]

Whether the industrial capitalist operates on his own or on borrowed capital does not alter the fact that the class of money capitalists confronts him as a special kind of capital, and interest as an independent form of surplus-value peculiar to this specific capital.[13]

Marx also notes that, within the three fractions sectorial divisions may also exist. This can be easily illustrated by a common example of price regulations and tariffs. For example, iron ore producers, seeking high output prices and high tariffs on foreign ore, conflict with steel producers, seeking low ore prices and elimination of tariffs on their inputs. Further, the existence of capitals which are highly concentrated and centralized, which can secure transfers of surplus through price fixing, locates further stratifications of the bourgeois class, that is, the division between monopoly and non-monopoly capital. Again, the requirement of the state as the cohesive factor in the social formation to reconcile these diversities is easily seen.

If left to themselves, Poulantzas remarks citing Marx, the bourgeoisie are not only exhausted by internal conflicts, but, more often than not, founder in oppositions incapacitating their ability to govern politically. The state apparatuses organize and smooth these stratifications by the formation of a “power bloc.” The structural determination of a power bloc is constituted by the fact that under capitalist production relations political coercion is not directly necessary for the extraction of surplus value in the labour process per se. This gives the state apparatuses a certain relative autonomy, so that the vicissitudes and transformations of relations within and between the state apparatuses do not directly threaten the continued production of surplus-value. Thus the state allows the “rule,” the “participation,” of many classes and fractions in a social formation via the unity established by the power bloc. Members participate in the power bloc so far as their political interests do not pertinently undermine the long range political interests of the hegemonic class. That is, the short term economic interests of the dominant classes and fractions of a social formation comprise a power bloc which organizes, unifies and maintains through a whole series of compromises, via policy, regulatory and political representation, the unstable equilibrium of the opposing classes and class fractions present. The hegemonic class or fraction effectively holds political power in a capitalist formation only in so far as its particular class interests are successfully generated as the universal and general interests–economic, political and ideological–of the entire social formation.

The first thing that the February Republic had to do was to complete the rule of the bourgeoisie by allowing, beside the finance aristocracy, all the propertied classes to enter the orbit of political power.[14]

The nameless realm of the republic was the only one in which both factions could maintain in equal power the common class interest, without giving up their mutual rivalry.[15]

Changes in the organization of the power bloc take place directly through political practices and representation. At any conjunction the “political scene” or “form of Regime” (Poulantzas) basically represents the relations of power between classes and fractions of the power bloc and exceptionally other class representatives.

From Poulantzas’ discussion of the power bloc follows his critique of the “state monopoly capital” theory of the state held by the communist parties and of all other conspiracy variants of the state which follow suit. The latter’s claim that the state is an “instrument” of the monopoly faction utilized through interlocking personnel is countered by Poulantzas primarily by holding up counter evidence such as his analysis of Fascist Germany run in the interests of monopoly, but where the state offices were strategically held by personnel recruited from the Petit-Bourgeoisie. Marx’s own examples from his writings on Britian are also cited. In addition the reformist strategies which derive from the “state monopoly capital” theory are also consistently attacked, as it follows, firstly, that if the positions of state power are held exclusively by the monopoly fraction then the interests of the non-monopoly fractions of the bourgeoisie are at odds with the state and the general condition exists for alliances between the working class and the competitive bourgeoisie; secondly, since the state is an “instrument,” a change of personnel (e.g., to the working class) will change the class nature of the state forgoing the necessity of “smashing” or “transforming” its apparatuses in structurally critical ways.

Parenthetically, I think that the “state monopoly capital” theory suffers from further theoretical inadequacies. The theory remains at such a high level of generality it is basically irrefutable. For example, if the state issues a policy clearly favoring monopoly the theory says it is because of the monopoly personnel running the state, but if on the contrary, policy is issued which is not in the direct immediate interests of monopoly then the theory will reply that it is only a calculated trick on the part of the state to deceive the workers. But from such logic it follows that any policy is neatly fitted into one or the other case ad hoc. The theory is of no theoretical import since no matter what goes on at the state level it is all explained away as part of a tactical move in the grand conspiracy. But without resorting to such theoretical subterfuge a state policy such as the Carter Inflation Program, for example, would be incomprehensible. For inflation itself does not conflict with the direct class interests of monopoly because of their price fixing abilities. In fact inflation increases the mass of profits accruing to monopolies by transferring value from the competitive bourgeoisie and lowering the real wages of workers. Thus, by proclaiming inflation the nation’s number one problem early in his administration Carter and the executive branch were offering strategic compromises (under severe pressures from competitive capital) to secure power bloc cohesion and to some extent defuse worker militancy. The actual resultant policy, the wage and price controls hammered out through committees by special interests and lobbyists, represented a condensation of the relation of class forces under the dominance by monopoly and as such understandably the so-called wage and price controls were in reality implemented as wage controls. Without theory of the power bloc such state activities remain undecipherable.

The overall unity of the state apparatuses, the forms of state and forms of regime, as presented by Poulantzas in Political Power and Social Classes, The Crisis of Dictatorships, and Fascism and Dictatorships, are determined by (A) The periodization of the capitalist mode of production, and (B) The world conjuncture of class forces. We will consider each in turn. Again Marx’s work provides the necessary background.

(A) In the Appendix to Vol. I of Capital,[16] “Results of the immediate Process of Production,” the periodization of capitalism is made between two characterizations of the labour-process: “the formal subsumption of labour under capital” and “the real subsumption of labour under capital.” Formal subsumption of labour characterizes capitalism under the dominance of “absolute” surplus value, and a lower level of development of productive forces. This limited development means that the socialization of labour is limited and restricted, the clear dominance of the capitalist mode of production in the social formation (meaning a small proportion of wage-workers to the total population) is generally lacking, the development of communication, transportation, and standardization of industry likewise is generally lacking–all restricting national bourgeois hegemony and class unity. In sum, an exposition is presented, by Marx, of the general battery of the foundations characteristic of capitalist social formations at early stages of development. Under the above conditions the class struggles of workers are generally individual and predominantly local. The attacks by capital on workers are almost exclusively over the extension of the working day and/or cuts in wages. Such struggles are necessitated and dictated by the falling rate of profit and the periodic crises which constantly disrupt capitalist production.

If the production of absolute surplus-value was the material expression of the formal subsumption of labour under capital, then the production of relative surplus-value may be viewed as its real subsumption.[17]

Two points seem to follow: Firstly, that the limits of absolute surplus-value signifies that worker demands for higher wages cannot be objectively met without lowering profits, and secondly, that the working class is small in number, disunified, and relatively weak. These economic conditions set the limits on stage action:

1.) The repressive apparatuses must play the dominant role, both because they necessitate little or no economic interventions and concessions, and because of their favored position in the match off–often taking a violent, though local form–with a disunited and numerically small working class.

2.) The ideological apparatuses play a subordinate role. Workers are generally restricted from participation in bourgeois political parties, universities, et cetera. However, the predominance of isolated and atomized practices in the labour process foster ideologies which focus on individual freedom and individual legal rights. These ideologies are reinforced by the results diffused on all the other apparatuses (for example schools study “freedom,” “rights,” Marriage = free legal contract, et cetera). The legal labour contract between two “equal” individuals conceals the real relationship of exploitation between unequal classes. Thus, instead of union and party organizing independently at the economic and political levels, this ideology encourages appeals to the state, the insurer of individual rights, by unorganized workers. This reveals the meaning behind Poulantzas’ comment that at an abstract level, the dominant ideology is displaced from the dominant region. That is, the dominant political/legal ideology under the formal subsumption of labour, displaces the class struggle of the proletariat away from the crucial region of the economic by discouraging organization there, encourages appeals to the state (for better education, fairer wages et cetera), and emphasizes individual abilities as responsible for low wages, employment, poor housing, and in short , the degree of exploitation.

While the imperatives for accumulation, i.e., reproduction on an extended scale, are continuous and unending, absolute surplus value (the extension of the working day) is limited both by the biological requirements of humans and the natural limitation of 24 hours. But on the contrary, relative surplus value has no such limit. The introduction of technology and the cheapening of the means of subsistence can become the dominant mode of surplus extraction, and thus usher in the “real subsumption of labour under capital,” where “the social forces of production of labour are... developed, and with large scale production comes the direct application of science and technology.”[18] The following general charcteristics are from the foundations which govern reproduction on an extended scale under the “real subsumption of labour under capital”:

1. Wage labour becomes more socialized, and accounts for the largest proportion of the population. That is, the capitalist mode of production asymptomatically tends toward exclusivity and total dominance within the social formation.

2. Monopoly conditions are particularly characterized by the tremendous reliance on technological advance to offset the falling rate of profit. This further leads to the socialization and standardization of labour, to the development of the “infrastructure” of production (energy, communications, transportation), etc. The end result: large numbers of proletariat are unified on the national level. Such conditions lead, unlike under formal subsumption, to the dominant ideology of technocratism; that is, the view, practice, etc., that changes which accompany technological advance occur as a result of higher productivity and efficiency, and ultimately yield benefits for everyone. Thus, the very processes under monopoly conditions most disunifying and vicious–degradation of labour and unemployment–are seen and treated as vital improvements eventually raising living standards for all.

3. Large amounts of surplus value are generated, much of which becomes redundant and uninvestible because the minimal investment for real growth requires an ever increasing value. Small, piecemeal investment produces lower, not higher, levels of productivity. “The minimum amount of capital in an industry increases in proportion to its penetration by capitalist methods and the growth in the social productivity of labour within it.”[19]

Domination by the repressive apparatuses becomes untenable under monopoly conditions where the social formation is polarized between a few exploiters and a mass of numerous, unified workers. But just as important, the generation of large amounts of surplus-value make possible the satisfaction of some of the demands of workers– demands which do not challenge the hegemony of the bourgeoisie. Thus, Marx says, under conditions of relative surplus-value, wages and the use-values they buy increase concurrently to a rising rate of surplus-value. Indeed, the value of labour-power and the value of working class articles of consumption fall as the intensity of labour increases. But note here the crucial distinction between nominal wages and prices of goods on the one hand, and on the other hand, real wages (the value of labour-power) and the value of goods. The two do not necessarily move in the same direction. Under such conditions the dominant mode of operation is displaced to ideological mechanisms. Apparatuses exist which operate especially to draw workers away from their “organic” (Gramsci) parties and organizations under the guise of “efficiency” and/or “universal harmony” (for example, bourgeois political parties, and class colloborating trade unions). This is the primary way in which ideological apparatuses operate to pacify and privatize the proletariat to submit to the “appropriate” authorities. Compromises can be made to the proletariat and certain of their demands met, in so far as they do not threaten the overall political interests of the hegemonic capitalist class fraction, or threaten the overall domination of labour by capital. All this serves to defuse the militancy of the workers.

Moreover, however much the individual manufacturer might give the rein to his old lust for gain, the spokesmen and political leaders of the manufacturing class order a change of front and of speech toward the work people. They had entered up on the contest for the repeal of the corn laws, and needed the workers to help them to victory.[20]

From the ones [proletariat] it [constitution] demands that they should go forward from political to social emancipation, from the others [bourgeoisie] that they should not go back from social to political restoration.[21]

As against the bourgeoisie, Bonaparte looks on himself at the same time, as the representative of the peasants and the people in general, who wants to make the lower classes of the people happy within the frame of bourgeois society. New decrees that cheat the true socialists of their stage craft in advance.[22]

Thus, political representatives evaluate policy in terms of political consequences. Disruption of the dominance/subordination relations between capital and labour is avoided by state measures and interventions which smooth over class relations yet remain within the frame of the dominant fraction and the power bloc. The latter is essential, for direct attacks on labour by the dominant elements of the economy are ultimately disruptive on both the inter and intra class levels. Interests of oppressed classes, and non-hegemonic but dominant class fractions, cannot be ignored, for the intensification of class struggles threatens the continued exploitation of the oppressed classes by capital and leads to a “loss of credibility” for the political rule of the bourgeois representative in government. Without far reaching support, even with some reservations, no state policy, or state measure can be implemented. Under such circumstances, in a “crisis of representation,” the capitalist state fails to be the cohesive factor for the entire social formation.

(B) During periods of smooth and relatively even accumulation in Department I and Department II socialization of labour advances, but simultaneously the countertendencies with respect to national cohesion advance. Thus, the economic and ideological/political process discussed above operate to disunite the dominated classes, mainly through bourgeois ideological inculcation. The result: a relatively weak proletariat and petit-bourgeoisie, a power bloc capable of undisrupted reproduction based on increasing rates of surplus-value and profit rates. Poulantzas considers this the normal state of affairs (even though often accused of taking the Bonapartist State as the normal state). This weakness of the proletariat and petit-bourgeoisie (the latter he says is “over-determined” in their isolation by economic isolation compounded by the dominant bourgeois ideology) is the basis of the distinction between the “liberal state” and the “interventionist state.”

1. The liberal state exists under competitive conditions and is marked (according to Poulantzas) by the mutual role of the three fractions of capital. The so-called “democratic structure” (dominance of ideology) allows the hegemony within the power bloc to trade off between the three fractions of capital without a critical “crises of representation.” So that in this sense the Liberal state displays a certain stability.

The nameless realm of the republic was the only one in which both factions could maintain in equal power the common class interest, without giving up their mutual rivalry.[23]

2. The interventionist state is characterized by the internationalization of capital in search of profits and state intervention in the economy. That is, economic state apparatuses became a necessary part of the reproduction of capital. For example, state sectors employ portions of the redundant population; and supply infrastructural products and services. Military contracts absorb highly technical output from Department I, and the state undertakes negotiations and supplies security for foreign investments. In the interventionist state the hegemonic position is held by a fraction of monopoly capital, while the other fractions of monopoly and competitive capital secure secondary yet supporting positions in the power bloc. Further, the non-hegemonic class fractions within the power bloc do achieve, at least partially, their interests via state measures to regulate bourgeois “co-respection” (Schumpeter).

A crisis of accumulation (relative to the other links in the imperialist chain) is the common element of the two “exceptional” forms of state: Fascism and Military dictatorship. In the case of fascism the analysis presented by Poulantzas basically concerns the attack by monopoly on the petit-bourgeoisie. The austerity inflicted occurs, so to speak behind their back, since at the political level these agents are drawn in mass into the state apparatuses by the fascist party. His analysis assumes the defeat of the working class prior to the actual transformation to the fascist form of state. This factor, the defeat/ non-defeat of the working class marks the essential differentiation between military dictatorship and fascism. Contrary to fascism, the military dictatorship is an attack directed by the repressive apparatuses on the working class, and less so on the petit-bourgeoisie. The aim of the military dictatorship is to break the militancy of the proletariat and to bring up the rate of surplus-value. In this way the state seeks to solve the crises of capital at the expense of labour and to continue the hegemony of the monopoly or “comprador” fraction. Dominance in the ensemble of state apparatuses accrues to the military, in which the organization of the hegemony of the various classes and fractions of the power bloc take place. Poulantzas comments in his book, The Crises of the Dictatorships that the rigidity of the military dictatorship renders this form of state very fragile. The exclusion of the masses from the state apparatuses makes effective compromise and national cohesion difficult, and rigidity of the military makes relations between members of the power bloc dangerously tenuous. For the discontented and often organized masses, held in check by repression, lurk behind every breach in bourgeois cohesion and vigorously offer often violent resistance to bourgeois rule.

The work of Nicos Poulantzas is a major contribution to the ongoing work in Marxist theory. And although Marx has left us only the crucial foundations of a scientific theory of history, Poulantzas’ work must be understood in light of the fundamental breakthroughs of Karl Marx. In particular, the absence of a clear discussion of the links between the economic level and the political level by Poulantzas–after all he says himself that the economy is “determinant in the last instance”–often leaves mistaken impressions of the real import of many of his arguments. I believe that Poulantzas has not only left us a contribution of major importance, but even more important has left us major uncompleted directions and tasks, tasks which include theoretical elaboration and articulation, and the great work of theoretically informed empirical study and confirmation.

[1] Marx, Karl, Selected Correspondence, p. 209, Moscow ed., Marx to Kugelmann, 11 July 1868.

[2] Marx, Karl, Capital Volume I, p.174, Moscow ed., 1971.

[3] Ibid, p. 180.

[4] Marx, Karl, Capital Volume III, p. 245.

[5] Ibid, p. 263.

[6] But his level of abstraction is inappropriate for a discussion of the specific determinations of which effects will dominate. States is only direction of tendencies not magnitudes. The latter requires specific empirical research concerning types of technical change, capacity utilization, work place transformations, etc.

[7] Marx, Karl, Capital Volume I, p. 715.

[8] Ibid, p. 598.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid, p. 542.

[11] Ibid, p. 688.

[12] Marx, Karl, Capital Volume III, p. 268.

[13] Marx, Karl, 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Selected Works, Volume I, Moscow 1973, p. 316.

[14] Marx, Karl, Class Struggles in France, Selected Works, Volume I, Moscow 1973, p. 212.

[15] Ibid, p. 251.

[16] Marx, Karl, Capital Volume I, Penguin Books, London 1976, p. 1019-1023.

[17] Ibid, p. 1025.

[18] Ibid, p. 1035.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Marx, Karl, Capital Volume I, op. cit., p. 267.

[21] Marx, Karl, Class Struggles in France, op. cit., p.236.

[22] Marx, Karl, 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, op. cit., p. 176.

[23] Marx, Karl, Class Struggles in France, op. cit., p. 251.