Written:

Not earlier than April 25 (May 7), but not later than September 1895

Source:

Lenin’s Collected Works, 4th Edition, Moscow, 1976, Volume 38, pp. 19 - 51

Publisher: Progress Publishers

First Published: 1930 in Lenin Miscellany XII

Translated: Clemence Dutt

Edited: Stewart Smith

Original Transcription & Markup: R. Cymbala &

Marc Szewczyk

Re-Marked up & Proofread by: Kevin Goins (2007)

Public Domain: Lenin Internet Archive (2003).

You may freely copy, distribute, display and perform this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works.

Please credit “Marxists Internet Archive” as your source.

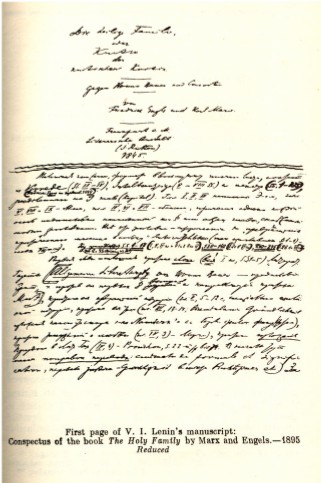

Conspectus of the book “The

Holy Family” by Marx and Engels was written by Lenin in 1895 during his first

stay abroad when he left Russia to establish contact with the Emancipation

of Labour group.

Note that this document has undergone special formating to ensure that Lenin’s

sidenotes fit on the page, marking as best as possible where they were

located in the original manuscript.

This little book, printed in octavo, consists of a foreword (pp. III-IV)[2] (dated Paris, September 1844), a table of contents (pp. V-VIII) and text proper (pp. 1-335), divided into nine chapters (Kapitel). Chapters I, II and III were written by Engels, Chapters V, VIII and IX by Marx, Chapters IV, VI and VII by both, in which case, however, each has signed the particular chapter section or subsection, supplied with its own heading, that was written by him. All these headings are satirical up to and including the “Critical Transformation of a Butcher into a Dog” (the heading of Section 1 of Chapter VIII). Engels is responsible for pages 1-17 Chapters I, II, III and sections 1 and 2 of Chapter IV, pages 138-142 (Section 2a of Chapter VI) and pages 240-245 (Section 2b of Chapter VII):

|

||

The first chapters are entirely criticism of the style (t h e w h o l e ( ! ) first chapter, pp. 1-5) of the Literary Gazette [[Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung of Bruno Bauer[3]—in their foreword Marx and Engels say that their criticism is directed against its first eight numbers]], criticism of its distortion of history (Chapter II, pp. 5-12, especially of English history), criticism of its themes (Chapter III, pp. 13-14, ridiculing the Gründlichkeit[4] of the account of some dispute of Herr Nauwerk with the Berlin Faculty of Philosophy), criticism of views on love (Chapter IV, 3 by Marx), criticism of the account of Proudhon in the Literary Gazette ((IV,4) Proudhon, p. 22 u. ff. bis[5] 74. At the beginning there is a mass of corrections of the translation: they have confused formule et signification,[6] they have translated la justice as Gerechtigkeit[7] instead of Rechtpraxis,[8] etc.). This criticism of the translation (Marx entitles it—Characterisierende Übersetzung No. I, II u.s.w.[9]) is followed by Kritische Randglosse No. I u.s.w.,[10] where Marx defends Proudhon against the critics of the Literary Gazette, counterposing his clearly socialist ideas to speculation.

Marx’s tone in relation to Proudhon is very laudatory (although there are minor reservations, for example reference to Engels’ Umrisse zu einer Kritik der Nationalökonomie [11] in the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher [12]).

Marx here advances from Hegelian philosophy to socialism: the transition is clearly observable—it is evident what Marx has already mastered and how he goes over to the new sphere of ideas.

(36) “Accepting the relations of private property as human and rational, political economy comes into continual contradiction with its basic premise, private property, a contradiction analogous to that of the theologian, who constantly gives a human interpretation to religious conceptions and by that very fact comes into constant conflict with his basic premise, the superhuman character of religion. Thus, in political economy wages appear at the beginning as the proportionate share of the product due to labour. Wages and profit on capital stand in the most friendly and apparently the most human relationship, reciprocally promoting one another. Subsequently it turns out that they stand in the most hostile relationship, in inverse proportion to each other. Value is determined at the beginning in an apparently rational way by the cost of production of an object and its social usefulness. Later it turns out that value is determined quite fortuitously, not bearing any relation to cost of production or social usefulness. The magnitude of wages is determined at the beginning by free agreement between the free worker and the free capitalist. Later it turns out that the worker is compelled to agree to the determination of wages by the capitalist, just as the capitalist is compelled to fix it as low as possible. Freedom of the contracting Parthei[13]” [this is the way the word is spelled in the book] “has been supplanted by compulsion. The same thing holds good of trade and all other economic relations. The economists themselves occasionally sense these contradictions, and the disclosure of these contradictions constitutes the main content of the conflicts between them. When, however, the economists in one way or another become conscious of these contradictions, they themselves attack private property in any one of its private forms as the falsifier of what is in itself (i.e., in their imagination) rational wages, in itself rational value, in itself rational trade. Adam Smith, for instance, occassionally polemises against the capitalists, Destutt de Tracy against the bankers, Simonde de Sismondi against the factory system, Ricardo against landed property, and nearly all modern economists against the non-industrial capitalists, in whom private property appears as a mere consumer.

“Thus, as an exception—and all the more so when they attack some special abuse—the economists sometimes stress the semblance of the humane in economic relations, while, more often than not, they take these relations precisely in their marked difference from the humane, in their strictly economic sense. They stagger about within that contradiction without going beyond its limits.

“Proudhon put an end to this unconsciousness once for all. He took the humane semblance of the economic relations seriously and sharply opposed it to their inhumane reality. He forced them to be in reality what they imagine themselves to be, or, more accurately, to give up their own idea of themselves and confess their real inhumanity. He therefore quite consistently represented as the falsifier of economic relations not one or another particular type of private property, as other economists have done, but private property as such, in its entirety. He has done all that can be done by criticism of political economy from the stand-point of political economy.” (39)

Herr Edgar’s reproach (Edgar of the Literary Gazette) that Proudhon makes a “god” out of “justice,” Marx brushes aside by saying that Proudhon’s treatise of 1840[14] does not adopt “the standpoint of German development of 1844” (39), that this is a general failing of the French, and that one must also bear in mind Proudhon’s reference to the implementation of justice by its negation—a reference making it possible to have done with this Absolute in history as well (um auch dieses Absoluten in der Geschichte überhoben zu sein)—at the end of p. 39. “If Proudhon does not arrive at this consistent conclusion, it is owing to his misfortune in being born a Frenchman and not a German.” (39-40)

Then follows Critical Gloss No. II (40-46), setting out in very clear relief Marx’s view—already almost fully developed—concerning the revolutionary role of the proletariat.

...“Hitherto political economy proceeded from the wealth that the movement of private property supposedly creates for the nations to an apology of private property. Proudhon proceeds from the opposite side, which political economy sophistically conceals, from the poverty bred by the movement of private property, to his conclusions negating private property. The first criticism of private property proceeds, of course, from the fact in which its contradictory essence appears in the form that is most perceptible and most glaring and most directly arouses man’s indignation—from the fact of poverty, of misery.” (41)

“Proletariat and wealth are opposites. As such they form a single whole. They are both begotten by the world of private property. The question is what particular place each occupies within the antithesis. It is not sufficient to declare them two sides of a single whole.

“Private property as private property, as wealth, is compelled to maintain itself, and thereby its opposite, the proletariat, in existence. That is the positive side of the contradiction, self-satisfied private property.

“The proletariat, on the other hand, is compelled as proletariat to abolish itself and thereby its opposite, the condition for its existence, that which makes it the proletariat, i.e. private property. That is the negative side of the contradiction, its restlessness within its very self, dissolved and self-dissolving private property.

“The propertied class and the class of the proletariat present the same human self-alienation. But the former class feels happy and confirmed in this self-alientation, it recognises alienation as its own power, and has in it the semblance of human existence. The class of the proletariat feels annihilated in its self-alienation; it sees in it its own powerlessness and the reality of an inhuman existnece. To use an expression of Hegel’s, the class of the proletariat is in abasement indignation at this abasement, an indignation to which it is necessarily driven by the contradiction between its human nature and its conditions of life, which are the outright, decisive and comprehensive negation of that nature.

“Within this antithesis the private property-owner is therefore the conservative side, the proletarian, the destructive side. From the former arises the action of preserving the antithesis, from the latter, that of annihilating it.

“In any case, in its economic movement private property drives towards its own dissolution, but only through a development which does not depend on it, of which it is unconscious and which takes place against its will, through the very nature of things, only inasmuch as it produces the proletariat as proletariat, misery conscious of its spiritual and physical misery, dehumnaisation conscious of its dehumanisation and therefore self-abolishing. The proletariat executes the sentence that private property pronounced on itself by begetting the proletariat, just as it executes the sentence that wage-labour pronounced on itself by begetting wealth for others and misery for itself. When the proletariat is victorious, it by no means becomes the absolute side of society, for it is victorious only by abolishing itself and its opposite. Then the proletariat disappears as well as the opposite which determines it, private property.

“When socialist writers ascribe this historic role to the proletariat, it is not, as Critical Criticism would have one think, because they consider the proletarians as gods. Rather the contrary. Since the abstraction of all humanity, even of the semblance of humanity, is practically complete in the fully-formed proletariat; since the conditions of life of the proletariat sum up all the conditions of life of society today in their most inhuman and acute form; since man has lost himself in the proletariat, yet at the same time has not only gained theoretical consciousness of that loss, but through the no longer removable, no longer disguisable, absolutely imperative need—the practical expression of necessity—is driven directly to revolt against that inhumanity; it follows that the proletariat can and must free itelf. But it cannot free itself without abolishing the conditions of its own life. It cannot abolish the conditions of its own life without abolishing all the inhuman conditions of life of society today which are summed up in its own situation. Not in vain does it go through the stern but steeling school of labour. It is not a question of what this or that proletarian, or even the whole proletariat, at the moment considers as its aim. It is a question of what the proletariat is, and what, in accordance with this being, it will historically be compelled to do. Its aim and historical action is irrevocably and clearly foreshadowed in its own life situation as well as in the whole organisation of bourgeois society today. There is no need here to show that a large part of the English and French proletariat is already conscious of its historic task and is constantly working to develop that consciousness into complete clarity.” (42-45)

|

“Herr Edgar cannot be unaware that Herr Bruno Bauer |

||

|

French equality with German

self-consciousness for an in- |

||

|

observation. Self-consciousness is man’s equality with |

||

|

“The opinion that philosophy is the abstract

expression |

||

|

“‘We always come back to the same thing... Proudhon |

||

|

write in the interests of self-sufficient criticism or out of |

||

|

icism,that will go as far as a crisis. Not only does Proud- “Proudhon’s desire to abolish non-owning and the old “Proudhon indeed does not oppose owning to non-owning, “Proudhon did not succeed in giving this thought appro- |

||

|

priate development.

The concept of ‘equal possession’ is a |

||

|

[[This passage is highly characteristic, for it shows how As a trifle, it may be pointed out that on p. 64 Marx Very interesting are: pp. 65-67

(Marx approaches the |

|

p. 76. |

(Section 1, first paragraph:

Feuerbach disclosed |

||

|

p. 77. |

(Last paragraph: anachronism

of the n a ï v e

relation |

||

|

pp.79-85. |

(All these seven pages are extremely interesting. |

||

|

pp. 92, 93— |

f r a g m e n t a r y

remarks against Degradie |

||

|

p. 101. |

“He” (Szeliga) “is unable ... to see that industry |

||

|

|

and trade found universal

kingdoms that are quite |

||

|

p. 102. |

(End of the first paragraph—barbed

remarks on the |

||

|

p. 110. |

Another example of ridiculing abstract specula- |

||

|

p. 111. |

A characteristic passage regarding Eugène Sue[20]: |

||

|

rier.[22] “It is precisely in that

relation that she” (gri- |

|||

|

p. 117. |

The “mass” of the sixteenth

and the nineteenth |

||

|

pp. 118-121. |

This passage (in Chapter VI: “Absolute Cri- |

|

“If, therefore, Absolute Criticism condemns some- |

|||

|

“The ‘idea’ always exposed itself to ridicule inso- |

NB |

||

|

asserts itself historically goes far beyond its real limits |

|||

|

“With the thoroughness of the historical action, the |

NB |

|

How far the sharpness of Bauer’s division into

Geist[26] |

||

|

Marx answers this by saying that the enemies of prog- |

||

|

Les grands ne nous paraissent

grands |

||

|

But in order to rise (122), says Marx, it is not

enough |

||

|

“Yet Absolute Criticism has learnt from Hegel’s Phen- |

||

|

In this way it is possible to prove, says Marx bitingly, |

||

|

Preoccupied with its “Geist,” Absolute

Criticism does |

||

|

“The situation is the same with ‘progress.’ In spite of |

||

|

“All communist and socialist writers proceeded from |

||

|

“What a fundamental superiority over the

communist |

||

|

“The relation between ‘spirit and mass,’ however, has |

||

|

And Marx points out that Hegel’s conception of history |

||

|

Hegel is “guilty of a double half-heartedness” (127): |

||

|

Bruno does away with this half-heartedness; he

declares |

||

|

“On the one side stands the Mass, as the

passive, spirit- |

||

|

As the first example of “the campaigns of

Absolute Crit- |

||

|

“One of the chief pursuits of Absolute

Criticism consists |

||

|

“This method, too, like all Absolute Criticism’s

original- |

||

|

In Section 2a (...“‘Criticism’ and

‘Feuerbach’—Damna- |

||

|

“But who, then, revealed the mystery of the

‘system’? |

||

|

“Once man is conceived as the essence, the

basis of all |

||

|

And after this, in regard to the opposition of

Spirit |

||

|

“Is Absolute Criticism then not

genuinely Christian- |

||

|

and materialism has been fought out on all sides and over- |

||

|

In regard to Bauer’s words: “To the extent

of the prog- |

||

|

“From this proposition one can immediately

measure |

||

|

Further, (pp. 143-167), the most boring,

incredibly |

||

|

The end of the section ((b) The Jewish Question

No. II. |

||

|

“Religious questions of the day have at

present a social sig- |

||

|

Herr Bauer does not suspect “that real,

worldly Judaism, |

||

|

It was pointed out in the Deutsch-Französische Jahr- |

||

|

“It was proved that the task of abolishing

the essence |

||

|

In demanding freedom, the Jew demands

something |

||

|

“Herr Bauer was shown that it is by no means

contrary |

||

|

And immediately following the above: |

||

|

“He was shown that as the state emancipates

itself from |

||

|

The Jews desire allgemeine Menschenrechte.[36] |

||

|

“In the Deutsch-Französische

Jahrbücher it was |

||

|

“He was shown that the recognition of the Rights |

||

|

“The Jew has all the more right to the

recognition of |

||

|

That the “Rights of Man” are not

inborn, but arose histor- |

||

|

Pointing out the contradictions of

constitutionalism, |

||

|

Industrial activity is not abolished by the

abolition |

||

|

Trade is not abolished by the abolition of trade

privileges |

||

|

with religion, “so religion

develops in its practical univer- |

||

|

...“Precisely the slavery of bourgeois

society is in ap- |

||

|

To the dissolution (Auflösung) (182) of the

political |

||

|

Anarchy is the law of bourgeois society

emancipated |

|

“The ideas”—Marx quotes

Bauer—“which the French |

||

|

“Ideas can never lead beyond an old

world order but |

||

|

The French Revolution gave rise to the ideas of communism In regard to Bauer’s statement that the state

must hold in “Therefore, it is natural necessity, essential human Robespierre, Saint-Just and their party fell

because they On the 18th Brumaire,[41]

not the revolutionary movement |

||

|

und Drang

[42] of commercial enterprise, the whirl (Taumel) |

|

[[This chapter (subsection d in the third section of

Chap- The French Enlightenment of the eighteenth century and |

||

|

against the metaphysics of

Descartes, Malebranch, Spin- |

||

|

The metaphysics of the seventeenth century,

defeated by There are two trends of French materialism: 1) from Des- The former, mechanical materialism, turns into French

nat- Descartes in his physics declares matter the only sub- “This school begins with the

physician Le Roy, reaches its Descartes was still living

when Le Roy transferred the At the end of the eighteenth century

Cabanis perfected From the very outset the metaphysics of the

seventeenth Voltaire (199) pointed out that

the indifference of the The metaphysics of the seventeenth century (Descartes, In the year of Malebranche’s death, Helvétius and Cond- Pierre Bayle, through his weapon of scepticism,

theore- This negative refutation required a positive,

anti-meta- Materialism is the son of Great

Britain. Its scholastic The real founder of English materialism was

Bacon. (“The “In Bacon, its

first creator, materialism has still concealed In Hobbes, materialism becomes one-sided,

menschen- Just as Hobbes

did away with the theistic prejudices

of Condillac directed Locke’s sensualism against seven- The French “civilised” (205) the materialism of the English. In Helvétius (who also

derives from Locke), materialism Lamettrie is

a combination of Cartesian and English

mat- Robinet has the most connection with metaphysics. “Just as

Cartesian materialism passes into

natural sci- Nothing is easier than to derive socialism

from the premis- Fourier proceeds immediately from the

teaching of the On pp. 209-211 Marx

gives in a note (two pages of small Of the subsequent sections the

following passage is worth “The dispute between Strauss and

Bauer over Substance “In the domain of theology,

Strauss quite consistently |

||

|

bach was the first to bring

to completion and criticise Hegel |

||

|

Marx ridicules Bauer’s “theory of

self-consciousness” on |

|

The following chapter (VII) again begins with a

series of Marx quotes from the

Literary Gazette the letter of a

“re- “Or”(!), exclaimed “the

critics” against this representa- |

|||||

|

of any single period in history which is actually known?” “Or does Critical Criticism”—Marx

replies—“believe that |

No- ta be- ne |

||||

|

Criticism dubbed this representative of the mass

a mas- “The criticism of the French and the English is not

an abs- [[The whole of Chapter VII

(228-257), apart from the pas- In Chapter VIII (258-333)

we have a section on the “Crit- “The mystery of this” (305)

(there was a quotation from |

|||||

|

thought. In Hegel’s

Phenomenology the material,

sensuous, |

|||||

|

a ‘thing of thought,’ a mere

determination of self-con- |

|||||

|

...“Finally, it goes without saying that if

Hegel’s Phe- |

|||||

|

|

|||||

“Thereby Rudolph unconsciously revealed the

mystery, “The

numerous charitable associations in Germany, the And Marx quotes from Eugène Sue: “Ah, Madame, it is not enough to

have danced for the be- On pp. 312-313 quotations

f r o m

F o u r i e r |

||

|

“It is superfluous to contrast to Rudolph’s

thoughts |

||

|

works of the materialist section of French communism.” (313) P. 313 u. ff., against the political-economic

projects of Section c) “Model Farm at Bouqueval”

318-320, Ru- |

||

|

320: “The miraculous means by which Rudolph

accomp- |

|

“Morality is ‘Impuissance mise en

action.’[65]

Every time ...“As in reality all differences boil down

more and more ...“Every movement of his soul is of infinite

importance to |

|

||

[1] The Holy Family, or Critique of Critical Criticism. Against Bruno Bauer and Co.—the first joint work of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. It was written between September and November 1844 and was published in February 1845 in Frankfort-on-Main.

“The Holy Family” is a mocking reference to the Bauer brothers and their followers grouped around the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (General Literary Gazette). While attacking the Bauers and the other Young Hegelians (or Left Hegelians), Marx and Engels at the same time criticised the idealist philosophy of Hegel.

Marx sharply disagreed with the Young Hegelians as early as the summer of 1842, when the club of “The Free” was formed in Berlin. Upon becoming editor of the Rheinische Zeitung (Rhine Gazette) in October 1842, Marx opposed the efforts of several Young Hegelian staff members from Berlin to publish inane and pretentious articles emanating from the club of “The Free,” which had lost touch with reality and was absorbed in abstract philosophical disputes. During the two years following Marx’s break with “The Free,” the theoretical and political differences between Marx and Engels on the one hand and the Young Hegelians on the other became deep-rooted and irreconcilable. This was not only due to the fact that Marx and Engels had gone over from idealism to materialism and from revolutionary democratism to communism, but also due to the evolution undergone by the Bauer brothers and persons of like mind during this time. In the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, Bauer and his group denounced “1842 radicalism” and its most outstanding proponent—the Rheinische Zeitung. They slithered into vulgar subjective idealism of the vilest kind—propagation of a “theory” according to which only select individuals, bearers of the “spirit,” of “pure criticism,” are the makers of history, while the masses, the people, serve as inert material or ballast in the historical process.

Marx and Engels decided to devote their first joint work to the exposure of these pernicious, reactionary ideas and to the defence of their new materialist and communist outlook.

During a ten-day stay of Engels in Paris the plan of the book (at first entitled Critique of Critical Criticism. Against Bruno Bauer and Co.) was drafted, responsibility for the various chapters apportioned between the authors, and the “Preface” written. Engels wrote his chapters while still in Paris. Marx, who was responsible for a larger part of the book, continued to work on it until the end of November 1844. Moreover, he considerably increased the initially conceived size of the book by incorporating in his chapters parts of his economic and philosophical manuscripts on which he had worked during the spring and summer of 1844, his historical studies of the bourgeois French Revolution at the end of the 18th century, and a number of his excerpts and conspectuses. While the book was in the process of being printed, Marx added the words The Holy Family to the title. By using a small format, the book exceeded 20 printer’s sheets and was thus exempted from preliminary censorship according to the prevailing regulations in a number of German states.

[2] Engels, F. und Marx, K., Die heilige Familie, oder Kritik der kritischen Kritik, Frankfurt a. M., 1845. —Ed.

[3] Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (General Literary Gazette)—a German monthly published in Charlottenburg from December 1843 to October 1844 by Bruno Bauer, the Young Hegelian.

[4] pedantic thoroughness—Ed.

[5] und folgende bis—and following up to—Ed.

[6] formula and significance—Ed.

[7] justice—Ed.

[8] juridical practice—Ed.

[9] characterising translation No. I, II, etc.—Ed.

[10] critical gloss No. I, etc.—Ed.

[11] Umrisse zu einer Kritik der Nationalökonomie (Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy) was first published by Engels at the beginning of 1844 in Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher (Franco-German Annals)—see Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Moscow, 1959, pp. 175-209.

[12] Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher (Franco-German Annals)—a magazine published in German in Paris and edited by Karl Marx and Arnold Ruge. The only issue to appear was a double number published in February 1844. It included Marx’s articles “A Critique of the Hegelian Philosophy of Law (Introduction)” and “On the Jewish Question,” and also Engels’ articles “Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy” and “The Position of England. Thomas Carlyle. ‘Past and Present’.” These works mark the final transition of Marx and Engels to materialism and communism. Publication of the magazine was discontinued chiefly as a result of the basic differences between Marx’s views and the bourgeois-radical views of Ruge.

[13] party—Ed.

[14] This refers to Proudhon’s work of 1840 Qu’est-ce que la propriété ou Recherches sur le principe du droit et du gouvernement (What Is Property? or Studies on the Principle of Law and Government). Marx presents a critique of this work in a letter to Schweitzer dated January 24, 1865 (see Marx and Engels, Selected Correspondence, Moscow, 1955, pp. 185-192).

[15] Marx is quoting Edgar.

[16] if the word may be allowed—Ed.

[17] “blacksmith”—Ed.

[18] “if the rich only knew it!”—Ed.

[19] debasing of sensuousness—Ed.

[20] This refers to Eugène Sue’s novel Les mystères de Paris (Mysteries of Paris), which was written in the spirit of petty-bourgeois sentimentality. It was published in Paris in 1842-43 and very popular in France and abroad.

[21] a student—Ed.

[22] worker—Ed.

[23] “from the outset”—Ed.

[24] Marx is referring here to articles by Jules Faucher entitled Englische Tagesfragen (Topical Questions in England), which were published in Nos. VII and VIII (June and July 1844) of the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung.

[25] at the end—Ed.

[26] spirit—Ed.

[27] mass—Ed.

[28] Loustallot’s journal of 1789—a weekly publication entitled Révolutions de Paris (Parisian Revolutions), which appeared in Paris from July 1789 to February 1794. Until September 1790 it was edited by Elisée Loustallot, a revolutionary publicist.

[29] The great only seem

great to us

Because we are on our knees.

Let us rise!—Ed.

[30] Phänomenologie des Geistes (Phenomenology of Mind) by G. W. F. Hegel was first published in 1807. In working on The Holy Family, Marx made use of Vol. II of the second edition of Hegel’s works (Berlin, 1841). He called this first large work of Hegel, in which the latter’s philosophical system was elaborated, “the source and secret of Hegel’s philosophy.”

[31] Doctrinaires—members of a bourgeois political grouping in France during the period of the Restoration (1815-30). As constitutional monarchists and rabid enemies of the democratic and revolutionary movement, they aimed to create in France a bloc of the bourgeoisie and landed aristocracy after the English fashion. The most celebrated of the Doctrinaires were Guizot, a historian, and Royer-Collard, a philosopher. Their views constituted a reaction in the field of philosophy against the French materialism of the 18th century and the democratic ideas of the French bourgeois revolution (see Holy Family ch.VI 3. d.).

[32] after the event—Ed.

[33] The refutation of the views expounded by Bruno Bauer in his book Die Judenfrage (The Jewish Question), Braunschweig, 1843, was made by Marx in an article entitled “Zur Judenfrage” (“On the Jewish Question”), published in 1844 in Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher.

[34] “in commercial and industrial practice”—Ed.

[35] “is the perfected practice of the Christian world itself”—Ed.

[36] the universal rights of man—Ed.

[37] The Universal Rights of Man—the principles enunciated in the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen” and proclaimed during the time of the French bourgeois revolution of 1789-93.

[38] does not conceive the general contradiction of constitutionalism—Ed.

[39] world order—Ed.

[40] “Yet it was I who made that.”—Ed.

[41] The 18th Brumaire (9 November 1799)—the day of the coup d’état of Napoleon Bonaparte, who overthrew the Directorate and established his own dictatorship.

[42] Storm and stress—Ed.

[43] a metaphysical universal kingdom—Ed.

[44] flows directly into socialism—Ed.

[45] Cartesian materialism—the materialism of the followers of Descartes (from the Latin spelling of Descartes—Cartesius). The indicated book—Rapports du physique et du moral de l’homme (Relation of the Physical to the Spiritual in Man) by P. J. G. Cabanis—was published in Paris in 1802.

[46] mould—Ed.

[47] became insipid—Ed.

[48] “whether matter can think?”—Ed.

[49] Nominalism—the trend in medieval philosophy that considered general concepts as merely the names of single objects in contrast to medieval “realism,” which recognised the existence of general concepts or ideas independent of things.

Nominalism recognised objects as primary and concepts as secondary. Thus, as Marx says in The Holy Family, nominalism represents the first expression of materialism in the Middle Ages (see Marx and Engels, The Holy Family, Moscow, 1956, p. 172).

[50] misanthropic, mechanical—Ed.

[51] Sensualism—the philosophical doctrine that recognises sensation as the sole source of cognition.

[52] sources—Ed.

[53] Babouvists—adherents of Gracchus Babeuf, who in 1796 led a utopian communist movement of “equals” in France.

[54] the most popular, though most superficial—Ed.

[55] Lenin is referring to Feuerbach’s Grundsätze der Philosophie der Zukunft (Principles of the Philosophy of the Future), 1843, which constitutes a continuation of the latter’s aphorisms Vorläufige Thesen zu einer Reform der Philosophie (Preliminary Theses on the Reform of Philosophy), 1842, in which the author expounds the basis of his materialist philosophy and criticises Hegel’s idealist philosophy.

[56] mass materialist—Ed.

[57] Fleur de Marie—heroine of Eugène Sue’s novel Mysteries of Paris.

[58] Anekdota zur neuesten deutschen Philosophie und Publizistik. Von Bruno Bauer, Ludwig Feuerbach, Friedrich Köppen, Karl Nauwerk, Arnold Ruge und einigen Ungenannten (Unpublished Recent German Philosophical and Other Writings of Bruno Bauer, Ludwig Feuerbach, Friedrich Köppen, Karl Nauwerk, Arnold Ruge and Several Anonymous Writers)—a collection of articles that were banned for publication in German magazines. It was published in 1843 in Zurich by Ruge and included Marx as one of its contributors.

[59] the law of the talion—an eye for an eye—Ed.

[60] criminal justice and justice for virtue!—Ed.

[61] plaything—Ed.

[62] bank for the poor—Ed.

[63] savings-banks—Ed.

[64] the institution—Ed.

[65] “impotence in action”—Ed.

[66] Tory philanthropists—a literary-political group—“Young England.”

This group was formed in the early 1840s and belonged to the Tory Party. It voiced the dissatisfaction of the landed aristocracy with the increased economic and political might of the bourgeoisie, and resorted to demagogic methods to bring the working class under its influence and use it in its fight against the bourgeoisie.

“In order to arouse sympathy,” Marx and Engels wrote in the Manifesto of the Communist Party, “the aristocracy were obliged to lose sight, apparently, of their own interests, and to formulate their indictment against the bourgeoisie in the interest of the exploited working class alone.”

Ten Hours’ Bill—a law on the l0-hour working day for women and juveniles, adopted by the English Parliament in 1847.

Ⅹ “According to Hegel, the criminal in his punishment passes sentence on himself. Gans developed this theory at greater length. In Hegel this is the speculative disguise of the old jus talionis [59] that Kant expounded as the only juridical penal theory. For Hegel, self-judgment of the criminal remains a mere ‘Idea,’ a mere speculative interpretation of the current empirical penal code. He thus leaves the mode of application to the respective stages of development of the state, i.e., he leaves punishment just as it is. Precisely in that does he show himself more critical than this Critical echoer. A penal theory that at the same time sees in the criminal the man can do so only in abstraction, in imagination, precisely because punishment, coercion, is contrary to human conduct. Besides, the practical realisation of such a theory would be impossible. Pure subjective arbitrariness would replace abstract law because in each case it would depend on official ‘honest and decent’ men to adapt the penalty to the individuality of the criminal. Plato long ago had the insight to see that the law must be one-sided and must make abstraction of the individual. On the other hand, under human conditions punishment will really be nothing but the sentence passed by the culprit on himself. There will be no attempt to persuade him that violence from without, exerted on him by others, is violence exerted on himself by himself. On the contrary, he will see in other men his natural saviours from the sentence which he has pronounced on himself; in other words, the relation will be exactly reversed.” (285-286)

| | | | | | |