Pr

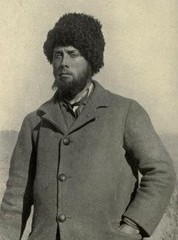

Preobrazhenskiy Yevgeny Alekseyevich (1886-1937)

Born in Orel, the son of priest, studied Law at Moscow University but did not finish. In 1903, he joined the Bolsheviks and carried out party work in Orel, Bryansk, Moscow, in the Urals, to Siberia.

Born in Orel, the son of priest, studied Law at Moscow University but did not finish. In 1903, he joined the Bolsheviks and carried out party work in Orel, Bryansk, Moscow, in the Urals, to Siberia.

In 1904-05, he member of Ural provincial bureau of the Party; from autumn 1909 in Irkutsk. From March 1917 delegate on the Chitinskogo Soviet. In 1917-18 a candidate member of the Central Committee of the Party. From January 1918, a candidate member of the Ural Provincial Committee of the Bolshevik Party. In 1917-18 joined the “Left Communists,” opposing peace with Germany, saying that “entire plan of Lenin appears, generally speaking, as an attempt to save the life of the Soviet regime by means of the suicide.”

From May 1918, President of the Presidium of the Ural Regional Committee, he directly participated in the killing of Nikolai II and his family.

Together with Bukharin, he wrote the “ABC of Communism” (1919); in 1920-21 Secretary of the Centrral Committee, and the member of the Politburo; in 1921 President of the Financial Committee and a member of the Council of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR; Chief of the People’s Commissariat of Education; leading Soviet of Economist 1920-30, developing the plan for industrialization of the country; an opponent of the NEP; one of the editors of the newspaper “Pravda,” in 1924, a supporter of Trotsky; 1924-27 a member of the Board of People’s Commissariat of Finance. After 1927, expelled from the party “for the organization of illegal antiparty printing house.” From January 1928, sent to the Urals and worked in the planning agencies. In summer 1929, together with Radek and Smilga wrote a letter claiming a “ideological and organizational break with Trotskyism.”

In January 1930, restored in the party and appointed to the Nizhniy-Novgorod Planning Committee; in 1932 member of the Board of the People’s Commissariat of the Light Industry, acting head of the People’s Commissariat of State Farms. In January 1933, expelled, arrested and interrogated by the GPU; sentenced to 3 years exile; finally expelled in 1936 and arrested again on 20 December 1936; he refused to confess and on 13 July 1937 sentenced to death and shot.

Rehabilitated in 1988.

See Evgenii A. Preobrazhensky Archive

Pribicevic, Branko (1928-2003)

Branko Pribicevic was one of the most prominent political scientists in the former Yugoslavia. He has earned his PhD in Oxford in 1957. His thesis was published in 1959 as “The shop stewards’ movement and workers’ control 1910-1922.” He was a member of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia and member of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Serbia.

Pribicevic’s major work was “Socialism – A World Movement” (1978), which was published as somewhat revised edition in 1991 under the title “Socialism – the Rise and Fall.”

See Branko Pribicevic Archive.

Price, Morgan Philips (1885-1973)

Son of a landowner and Liberal MP. Educated at Cambridge; went to Russia in 1914 as correspondent for the Manchester Guardian. Wrote against the allied intervention and in support of the Soviet government, but never joined the Communist Party of Great Britain. On return to Britain in 1919 he associated with the Independent Labour Party and the Labour Party. Acted as correspondent for the Daily Herald during the revolutionary events of 1919-23 in Germany. Labour MP for Whitehaven 1929-31; for the Forest of Dean 1935-50. Held various minor government posts. Wrote of his experiences in Russia in My Reminiscences of the Russian Revolution (1918), and in retrospect as a reformist in My Three Revolutions (1969).

Son of a landowner and Liberal MP. Educated at Cambridge; went to Russia in 1914 as correspondent for the Manchester Guardian. Wrote against the allied intervention and in support of the Soviet government, but never joined the Communist Party of Great Britain. On return to Britain in 1919 he associated with the Independent Labour Party and the Labour Party. Acted as correspondent for the Daily Herald during the revolutionary events of 1919-23 in Germany. Labour MP for Whitehaven 1929-31; for the Forest of Dean 1935-50. Held various minor government posts. Wrote of his experiences in Russia in My Reminiscences of the Russian Revolution (1918), and in retrospect as a reformist in My Three Revolutions (1969).

See Morgan Philips Price Archive.

Princip, Gavrilo (1895-1918)

Bosnian student member of secret patriotic organisation to free his country from Austria. Shot Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife on 28 June 1914 at Sarajevo. Sentenced to life imprisonment, and died shortly thereafter in prison.

Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1809-1865)

French political economist and acknowledged by Bakunin as the founder of anarchism, envisioned a society of independent, self-employed artisans.

French political economist and acknowledged by Bakunin as the founder of anarchism, envisioned a society of independent, self-employed artisans.

Proudhon came from humble origins, a printer by trade, but during the 1840s he became well-known throughout Europe. Proudhon was the first person to call himself an “anarchist,” the word previously only having been used as a term of abuse, during the French Revolution. He called his anarchism “mutualist socialism.”

His most famous book was What is Property? (1840) (“it is theft,” he responded), but his other works include De la célébration du Dimanche (1839), De la création de l'ordre dans l'humanité (1843) and Système des contradictions économiques, ou philosophie de la misère, (in 2 volumes, 1846). A persistent critic of the French July Monarchy, he was nonetheless surprised by the outbreak of hostilities in Paris in February 1848. In his correspondence, he recounted his participation in the February uprising and the composition of what he termed “the first republican proclamation” of the new republic. The same correspondence indicates, however, that Proudhon had misgivings about the new government because it was pursuing political reform at the expense of socioeconomic reform, which Proudhon considered basic.

Determined to set the new republic on the correct course, Proudhon published his own perspective for reform, Solution du problème social, in which he articulated a program of mutual financial cooperation among workers that he believed would transfer control of economic relations from capitalists and financiers to workers. Pivotal here was his plan to establish a bank which would provide credit at a very low rate of interest and issue “exchange notes” that would circulate in lieu of money based on gold.

Proudhon made his biggest impact on the public during the Second Republic through his journalism. He was connected with four different newspapers: La Représentant du Peuple (February 1848-August 1848); Le Peuple (September 1848-June 1849); La Voix du Peuple (September 1849-May 1850); Le Peuple de 1850 (June 1850-October 1850). His polemical writing style, combined with his perception of himself as a political outsider, produced a cynical, combative journalism which alienated some, but appealed to many French workers. In his numerous articles he criticised the policies of the government and continued to propose the reform of credit and exchange. To realise his plan, he attempted to establish a popular bank (Bank du Peuple) early in 1849, but despite recruiting more than 13,000 subscribers, receipts were meagre and the enterprise never took off.

Proudhon failed to get elected to the constituent assembly in April 1848, though his name appeared on the ballots in Paris, Lyon, Besançon, and Lille. He was successful, however, in the complementary elections held on June 4, and was therefore a Deputy during the debates over the National Workshops. Proudhon had never advocated such workshops, perceiving them as essentially charity institutions which did not threaten the economic system, but he opposed their elimination unless some economic assurances could be given to the workers who relied on them for subsistence.

Proudhon was shocked by the violence of the June Days. He visited the barricades personally to acquaint himself with the events that were unfolding and reflected in 1855 that his presence at the Bastille at this time was “one of the most honourable acts of my life.” But in general during the tumultuous events of 1848, Proudhon opposed insurrection and preached peaceful conciliation, a stance that was in accord with his lifelong stance against violence. He never fully approved of the revolts and demonstrations of February, May, or June, 1848, though he sympathetically portrayed the social and psychological injustices that the insurrectionaries had been forced to endure, and argued that the forces of reaction were the responsible parties for the occurrence of these tragic events.

Following the June Days, Proudhon faced the criticism of conservatives within the national assembly, especially for the economic reforms that he continued to advance. Following a heated exchange within the committee of finance of the national assembly (of which Proudhon was a member), Proudhon’s proposals were condemned on the floor of the assembly by Adophpe Thiers. Proudhon responded with a three-and-a-half-hour speech on July 31 in which he argued that the abrogation of property was the essential economic meaning of the 1848 revolution and insisted that the country should “proceed with the social liquidation.” The speech was frequently interrupted by pointed rejoinders from the floor of the Assembly and was followed by a motion of censure that was supported even by Louis Blanc and Pierre Leroux.

As this vote indicated, Proudhon’s relationship with the Montagne was strained. Though there was a brief attempt to form a new left-wing coalition in the fall of 1848, this failed because, in Proudhon’s opinion, the Montagne remained attached to political revolution rather than social revolution. Proudhon and the Montagne could put aside their differences long enough to vote together on November 4 against the new constitution (though for different reasons), but by the end of the month they were again at each others throats.

Proudhon also had a run-in with the new President of the Republic, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, which led to his prosecution and imprisonment. Proudhon had opposed Bonaparte throughout 1848: he had criticised him in two articles in Le Représentant du Peuple in June 1848; he voted against allowing him to take a seat in the Constituent Assembly; he opposed the creation of a strong Executive elected directly by the people; he opposed Napoleon in the presidential elections of December 1848. Proudhon’s attacks became more aggressive in January 1849, and the government responded by getting the assembly to lift Proudhon’s immunity from prosecution and, in March 1849, had Proudhon sentenced to three years in prison and fined 3000F. Proudhon went into hiding for two months, although he continued to write articles for Le Peuple, but on the night of June 5 he was arrested and transferred to Sainte-Pélagie.

During his three years in prison, Proudhon married and fathered a son, and wrote and published four books. The first, Confession d'un révolutionnaire (November 1849) was Proudhon’s personal account of the 1848 revolutions. The second, Idée générale de la révolution au XIXe siècle (July 1851), discussed the specific the specific reform proposals that Proudhon had articulated in Solution du problème sociale, but placed them in the context of the inevitable historical progression toward greater liberty and equality that Proudhon termed “revolution.” La Révolution sociale demontrée par le coup d'état du 2 decembre 1851 (July 1852), was an appeal to Louis-Napoleon to work for the revolution by implementing social reforms. Philosophie du progrès (September 1853), was more philosophical in nature and had little to do with the Revolutions of 1848.

Proudhon’s actions and writings during this period have always been controversial. Though clearly on the political left, his opposition to the provisional government and his public quarrels with prominent socialists like Louis Blanc made him unpopular with the Montagne. His attacks of Bonaparte, followed by his book urging him to embrace a progressive and “revolutionary” program, have caused confusion and led to criticism. His stances concerning politics — opposition to universal suffrage followed by election to the constituent assembly and insistence that Bonaparte institute reforms “from above” — has made it easy to dismiss Proudhon as hopelessly inconsistent. However, Proudhon did pursue a consistent social program, one that he hoped to see implemented by different parties at different phases of the revolution. His general goal was to return the control of the productive process back to workers by ensuring that workers owned their own means of production, assisted by reforms of credit and exchange. The masthead slogan of his paper in 1848, Le Représentant du Peuple, stated it clearly: “What is the producer in actual society? — Nothing. What should he be? — Everything.”

Thrust into the public sphere by tumultuous events of 1848, Proudhon proved to be an ineffective political actor. As he himself perceptively noted in 1850, he was basically a “man of polemics, not of the barricades.”

Nevertheless, Proudhon’s ideas have continued to have influence up to the present day, especially in France, and the widespread movement for setting up intentional communities has its ideological roots in Proudhon’s ideas (see Utopian Socialism Archive). See also:

- Proudhon Archive,

- Marx’s critique of Proudhon.

- Conflicting Elements in The International, on Proudhon’s following in France;

- Anarchism Archive.