Neocolonialism by Kwame Nkrumah 1965

ON 30 June 1960, when the Congo became independent, there began what will undoubtedly be regarded by historians as the most stormy and complex chapter in that country’s, and for that matter Africa’s, history. Within a few weeks there was a breakdown of law and order when soldiers of the Force Publique, disappointed because independence did not bring immediate improvement in their position, seized arms, arrested white officers and N.C.O.s and finally broke up into rioting bands. It was at this point that Moise Tshombe, with the help of Belgian advisers, began the proceedings which led to the secession of Katanga Province. The newly independent Republic of the Congo was crippled by disorder and unrest.

The story of the United Nations intervention and Lumumba’s murder are well known, and so also are the political events which have followed. Less publicised, for obvious reasons, have been the involved economic aspects of the whole Congo tragedy. Yet these are in many ways the more significant and certainly the more sinister since they are dominated by foreign interests whose main concern has always been for their own private gain.

There was not much American investment in the Congo before 1960. What there was, was largely indirect, through Tanganyika Concessions and Union Minière and the Anglo American holdings of the Oppenheimer group, and came mainly from the Rockefeller group. This group also had participations in the important textile company, Filatures et Tissages Africains, created in 1946 by the Cotton Union and the Société Générale. The Rockefeller family holds 60,000 shares, of which 3,000 are in the hands of Nelson Rockefeller and 26,438 belong to Laurence Rockefeller, who also has minority interests in two other companies of the Société Générale’s group: Cie Générale d'Automobiles et d'Aviation au Congo and Les Ciments du Congo. He owns about 14 per cent of the capital of the company for the manufacture in the Congo of metal boxes and all other articles from enamelled sheets, and the same share in the Congo company for the production and trade in pineapples, ANACONGO. In 1952 both Laurence and David Rockefeller participated in acquiring about 30 per cent of Syndicat pour l'Etude Géologique et Minière de la Cuvette Congolaise. All petroleum products used in the Congo continue to be imported from abroad and the giant Rockefeller trust, l'Esso-Standard, created a distribution subsidiary in the Congo in 1956, l'Esso Congo Belge, rechristened Esso Central Africa in 1960. Another subsidiary, the Socony Vacuum Petrol Company and Texas Petroleum, have minority participations in the Société Congolaise d'Entre Posage des Produits de Petrole.

There are some American plywood companies there, such as United States Plywood Corporation, with Agrifor and Korina-congo, and in the Syndicat du Papier. Pluswood Industries has an agreement with Cominière, who have together formed the Société Congolais Belgo-Americaine pour la Transformation du Bois du Congo – SOCOBELAM. Olin Mathieson Industries, which have interests in the Pouderies Réunies de Belgique, have participated with Union Minière and several other groups of the Société Générale in creating the Société Africaine d'Explosifs – AFRIDEX. Olin Mathieson have a fifth of the capital. Others investing there include the Industrial and Investing Corporation, New York, Armco Steel, Bell Telephone, General Motors and Otis Elevators.

Since 1960 the Bank of America has acquired 20 per cent in the Lambert Bank group’s Socobanque; Ford has founded Ford Motors (Congo); Union Carbide has taken a dominant participation in Somilu, created in 1960 to exploit a pyrochlore mine. This mineral contains niobium, a rare metal used in making special steels. David Rockefeller made a tour to the Congo in 1959, for ‘information’, after which his group took up 1,030 out of 26,000 shares in Société de Recherches et d'Exploitation de Bauxites au Congo – BAUXICONGO. In June 1960 he announced that he would take up about eight per cent of the 65 millions of capital in the Cie du Congo pour le Commerce et l'Industrie and C.C.C.I. Dillon Read & Co. and J. H. Whitney & co., bankers of New York, have created an investment company to examine the possibilities of American investment in the Congo. This is the American Eurafrican Fund.

Interesting as this American penetration into the Congo is, of more immediate concern is the continuing Belgian domination of so much of the Congo’s economy. In Les Trusts au Congo by Pierre Joye and Rosine Lewin, a clear picture of the events immediately preceding and following independence is given.

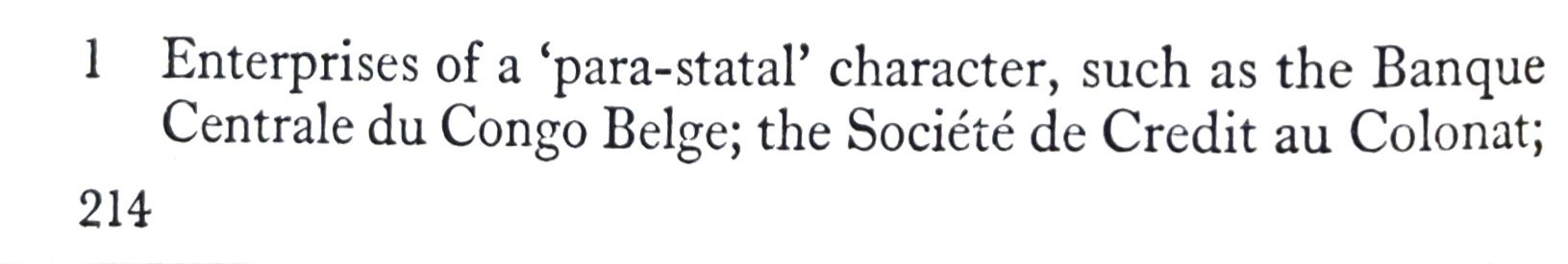

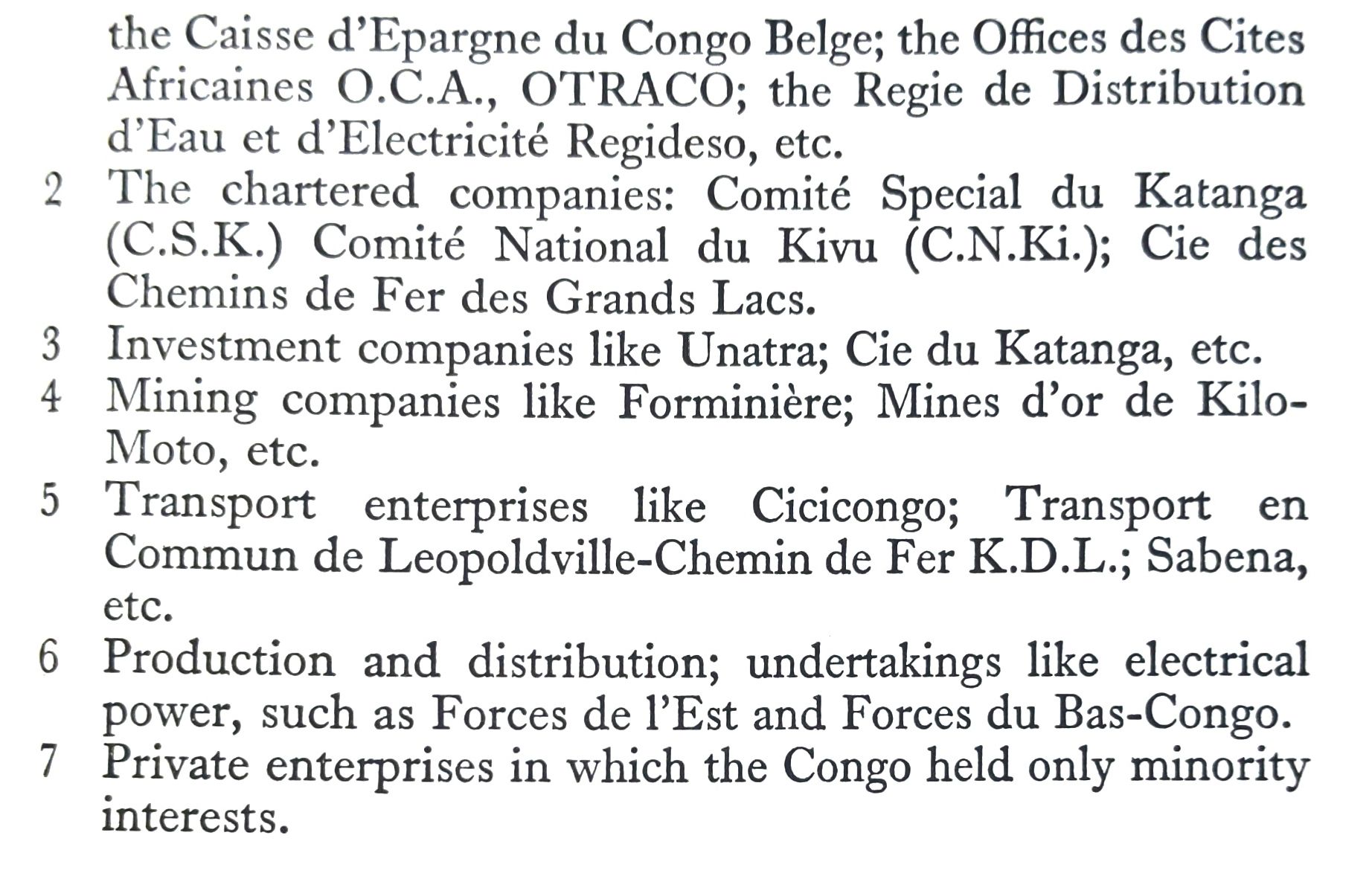

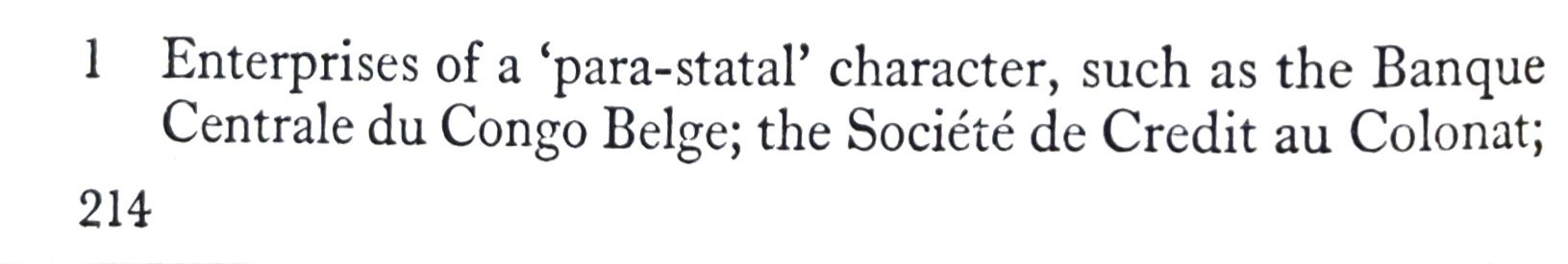

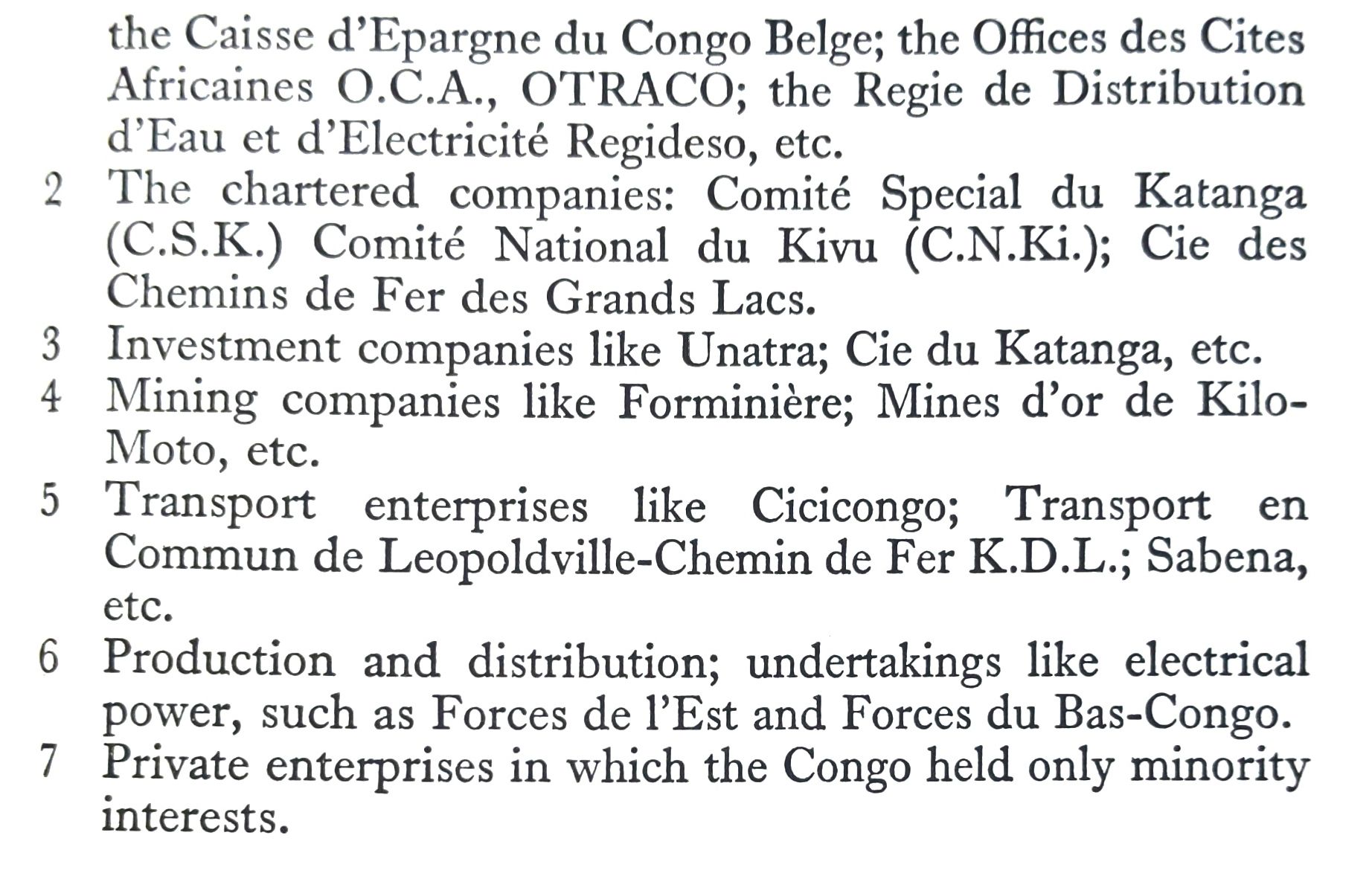

According to their account, the independent State of the Congo, under Leopold II, owned a large part of the capital of the original companies, also of the ‘chartered companies’ created at the time, and of private enterprises. After the Belgian Government took over the administration of the Congo, these participations were increased in a number of ways: by direct intervention in the creation of new organisms of a ‘para-statal’ nature; by the arrogation of certain rights as recompense for the concessions they gave; by exercise of right to subscribe to the increase of the capital of companies in which the Congo State already owned shares. As a result the Belgian Congo held a considerable portfolio of investments which, at the most moderate estimate, were valued at about 40 million francs. In addition it possessed various prerogatives, such as voting rights and the right to nominate representatives to administrative boards, in a whole series of enterprises in which it did not hold capital participations. This portfolio comprised participations and rights in:

The possession of this important portfolio permitted the public authorities, in principle, to exercise a considerable influence in the Congo economy and even to control completely certain important sectors. Moreover, official statements justified these participations, declaring that they allowed the State to exercise its role of ‘guardian of the public interest and tutor of the natives’.

The example of the C.S.K. is significant in this respect. Leopold II had controlled this semi-public organism by reserving to the State the right to nominate four out of the six members of its administration. But after the taking over of the Congo by Belgium the C.S.K. was, during fifty years, the docile instrument of the Union Minière, although it had every opportunity to control the great Katanga trust. C.S.K. was by far the biggest shareholder of Union Minière, and the statutes elaborated in 1906 officially conferred on it important rights in Union Minière, notably that of designating the administrative council and a certain number of directors. C.S.K. never used these rights, but on the contrary confided its representation to the most obvious leaders of private capital. The hold of the trusts on the Congo administration was total, the more so since the big companies were able to ensure considerable material advantages to the representatives of the State who passed into their service.

Before June 1960 the trusts speeded up their manoeuvres to prevent the Congolese people from coming into possession of their patrimony. At the time of the Round Table Conference, the financial press was emphatically insisting on the Belgian government obtaining guarantees from the future Congo Republic. ‘In the very first place, it is necessary to shelter the enterprises from eventual nationalisation.’ The Congolese nationalist parties were, however, unanimous in opposing the maintenance by the Belgian financial groups of an economic protectorate over the Congo after 30 June 1960.

Consequently, they insisted that the Congo portfolio should be transferred integrally and without conditions to the young Republic, which would be able to make use of the rights arising from it to name its own representatives on the ‘para-statal’ organisms and, if such should be the case, in the private Congolese companies. It was this which frightened Belgian financial circles; the prospect of seeing the Congo Republic making use of the incontestable rights that the possession of the Congolese portfolio would confer upon it.

To avert this, Raymond Scheyven vainly tried the manoeuvre which was quickly recognised by the Congolese leaders: he proposed to answer the financial needs of the Congo by creating a ‘mixed investment company’, to which the Congo would confer the management of its portfolio, Belgium on its side bringing an annual contribution of one billion francs. If this attempt failed, the Belgian government was all the happier in the case of the chartered companies, whose dissolution in extremis it would decree a few days before 30 June. It also decided to dissolve C.S.K. and C.N.Ki. before Congo acceded to independence.

On the occasion of the Round Table Conference, Scheyven parleyed with certain Congolese delegates, whom he tried to persuade that it would be better if the Belgian government itself proceeded with this measure before 30 June. He made them believe that it was preferable because, if the Congolese government did it afterwards, this could create a bad impression abroad, giving rise to the belief that they had something against the private companies.

The manoeuvre was clever. It was easier to convince the Congolese delegates, since most of them showed an understandable distrust towards the chartered companies. They had only too often had occasion to declare that the companies played the game of the big trusts. As to these, certain Congolese parties had called for the dissolution of the companies and the transfer of their rights to the Congolese State.

The Belgian officials charged with giving technical enlightenment to the participants at the Round Table Conference were openly careful to indicate that the Congo Republic could repay the colonialists for their part, by using in the interests of the Congolese people the prerogatives in the companies which would devolve upon the State.

A hurried decree of 27 June 1960, three days before the proclamation of independence, sanctioned the dissolution of the C.S.K. and the division of its assets between the Congo and the Cie du Katanga. At a stroke the Congo Republic lost the possibility of utilising the powerful instruments of command which it would have disposed of in taking over the direction of the C.S.K. and the prerogatives of the Union Minière were preserved.

Through the intermediary C.S.K., which would have in fact become a Congolese para-statal organism, the Congo Republic would in effect have obtained the statutory right to designate the president of the Katanga trust and a certain number of other directors on its board. And the Congolese government could even have pre-empted its views in the general meetings of the Union Minière, through the C.S.K., which was the biggest shareholder of the company.

The dissolution of the C.S.K. not only lost to the Congo Republic the possibility of benefiting from the prerogatives of this organism. The convention of 27 June 1960 accorded considerable additional advantages to the Cie du Katanga, which received full ownership of a third of the lands improved by the C.S.K. (allotment zones), its real estate and bankings, as well as the right to a third of the rents which were expected in the future from the mineral concessions allocated by C.S.K.

If the ground rights and mineral rights not already conceded revert to the Congo, this restitution of rights over the Congolese land and mineral patrimony will not be effected without compensation, since the convention stipulates that the Congo Republic must pay in compensation a forfeiture indemnity of 100 million to the Cie due Katanga.

The C.N.Ki. was formed for a period which will expire on 31 December 2011. Here again, it would have been sufficient if the Congolese government utilised the rights conferred on it by statute to exercise a preponderant influence in this ‘para-state’ organism. The Belgian authorities, however, concluded with the officials of the C.N.Ki. a convention which decided that the Belgian Congo would withdraw purely and simply as a concession partner and renounce at the same time all its rights in association.

A decree issued on 30 May 1960 approved this convention and, by a stroke, C.N.Ki. ceased to be a semi-official organism. On 21 June 1960 its shareholders decided, in addition, to transform it into a common stock company called the Société Belgo-Africaine du Kivu – SOBAKI. This company reserved the right to exploit for its own private profit exclusively the mines of C.N.Ki. as well as the integral property of the portfolio which this organism had constituted. If the public authorities take over the administration of the crown lands, the convention provides that the shareholders of Sobaki shall receive in compensation ‘a just indemnity’.

To give an appearance of legality to these conventions, the representatives of the Belgian government declared that they acted ‘in accordance with the wishes expressed by the economic, financial and social conference which took place in Brussels in the months of April and May 1960’. In reality, in pronouncing the dissolution of the C.S.K. and the C.N.Ki. the Belgian authorities wanted, above all, to place before the new Congolese State an accomplished fact.

In order to show how indispensable the financial support of Belgium was, the Belgian companies had, in fact, taken care to make massive withdrawals of capital at the same time as they pushed to the maximum the export of Congolese products, and on the other hand, limited to the extreme their imports. The Congolese trade balance resulting from the action gave an exceptionally high surplus in 1959 (13,418 million francs), which did nothing to save the Congo from very great financial difficulties. In fact, a heavy proportion of the sums anticipated from the sale of Congolese products were not returned to the colony, and more than seven billions of private capital left the Congo in the course of the exercise.

These manoeuvres have cost the young African State sad convulsions and have brought it to the edge of chaos. And they have done nothing to resolve the essential problem for the future of the Congo: how to recover from under-development.