Neocolonialism by Kwame Nkrumah 1965

AMERICAN and European companies connected with the world’s most powerful banking and financial institutions are, with the consent of African governments, entering upon major projects designed to exploit new sources of primary products. In some cases these are allied to long-term ventures for the establishment of certain essential industries. In the main, however, they are confining themselves to the production of materials in their basic or secondary stages, with the object of transforming them in the mills and plants owned and run by the exploiting companies in the metropolitan lands.

Africa has failed to make much headway on the road to purposeful industrial development because her natural resources have not been employed for that end but have been used for the greater development of the Western world. This has been a continuing process that has gained tremendous momentum in recent years, following the invention and introduction of new processes and techniques that have quickened the output of both the ferrous and non-ferrous metal industries of Europe and America in order to keep pace with the ever-increasing demand for finished goods. Military preparations and nuclear expansion have had a considerable impact upon this demand. World output of crude steel almost doubled itself in the decade between 1950 and 1960, from 190 million tons to 340 million tons. Even the regression of 1958 which lasted through the following years failed to halt the progress, which went on in lesser degree in both Eastern and Western countries.

The general forecast is that this tempo of production will be maintained. As it comes from Western sources, it makes little allowance for expansion of African use of primary products, and envisages a continuance of the present flow as between developing source countries and highly industrialised users. Nor does it take into account the likelihood of a repressive tendency in Western economies that can certainly affect the demand for raw materials. A publication of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe in 1959 estimated that the world production of steel between 1972 and 1975 will be in the region of 630 million tons. Before the last war most of the Western world’s iron and steel output was based upon local raw materials. The post-war years, particularly since 1956, have seen an opposite trend. Something like a quarter of the raw materials (90 million tons out of 400 million) used in the world’s metallurgical industries have been imported.

The countries mainly importing these raw materials are the United States, Western Europe, and Japan. The Soviet Union and the developing countries have at their disposal sufficient quantities of domestic raw materials. At the present time three large areas of primary resources are being exploited for the benefit of the great producer countries. These are Africa, Canada, and South America; in particular Chile and Peru and lately Venezuela. Canada has become a province of American capital investment, which draws off high profits and exploits vast resources of raw products for conversion in American plants. South America and Africa, besides offering these advantages, provide cheap labour and local governmental assistance by way of duty exemption for imported machinery and equipment as well as tax remission.

Surveys now being carried out in Africa are discovering more and more deposits of valuable raw materials. Western investigators regard them essentially as sources of exploitation for the commerce and industry of their world, ignoring completely the development of the countries in which they lie. Robert Saunal, in an article in Europe (France) Outremer of November 1961 surveys the possibilities of Africa as a provider of ferrous raw materials for the industries of the great metallurgical countries. He reminds his readers that there are sources of these primary materials in Europe, such as Sweden and Spain, and that for Japan there are the countries of Asia and Oceania.

He concludes that European participation is a favourable factor in starting off the exploitation of Africa’s mineral resources, but that the new productive capacities in course of development should counsel prudence and a detailed examination of the selling possibilities. These mines are bound to start off in a situation of lively competition, which must have its effect upon price levels. They need, therefore, to be subjected to close preliminary examination before being embarked upon and must depend upon agreement between the exploiting companies and the host States which will give the former a just return and the latter a stable fiscal regime for the functioning of the ‘harmonised exploitation’. In short, the governments of the new States are seen in the role of policemen for the banking and industrial consortia bent upon continuing the old imperialist pattern in Western-African relationships. The ‘stable fiscal regime’ they will guarantee out of such exploitation will, according to Robert Saunal, be based on conditions of depressed prices arising from acute competition.

There has been a considerable increase in the production of primary materials in Africa since 1945, under the stimulus of post-war rebuilding needs throughout the world, and the exigencies of cold-war stock-piling and armaments requirements. Another driving factor has been the revolution in productive methods and management. The surge of colonial peoples towards independence must also be acknowledged as a force contributing to the extension of raw materials production.

In some cases the production of primary materials since 1945 has multiplied several times, and in most cases has doubled. The scene in Guinea shows much change, following the discovery of deposits of iron and bauxite. Diamond mining has also made noticeable progress. The Ivory Coast in 1960 was producing diamonds at an annual level of about 200,000 carats, and operations have started in the manganese fields in the neighbourhood of Grand Lahou. Calcium phosphate is being exploited in Senegal, and aluminium and oxidised sand provide some mining activity. The mining of iron ore is under way in Mauritania, where an Anglo-French consortium is planning to produce four million tons as a first stage, to be increased later to six millions tons annually. Deposits are estimated at around 115 million tons of 63 per cent iron grade. Finds of very rich phosphate deposits in Senegal have brought a French-Belgian financial and mining combination into the country to carry out their exploitation. An estimated 40 million tons of raw phosphates are expected to allow a production of 13 million tons of rich phosphates through the extraction of 600,000 tons of concentrates annually for twenty years.

Phosphates have also been found in Togo, which are to be exploited by a consortium associated with the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas and established mining companies having connections with the Société Générale de Belgique. Manganese, uranium, oil and iron ore finds in Gabon have brought in similar consortia for their exploitation. Cameroun produces little from mining beyond some small amounts of gold, tin and rutile. Though there has been no effective change in Madagascar’s position, there have been discoveries of uranium, monozite, zircon, chromium and other minerals, whose exploitation is being investigated. Iron ore finds in Algeria are estimated at 100 million tons, and we have been hearing a good deal lately about the oil and gas resources of the Sahara desert. Algeria’s fields are now producing at the rate of 450,000 barrels a day (about a third of those of Iran), and Libya has reached 150,000 barrels daily, with the anticipation of achieving 600,000 barrels a day within the next five years. In Algeria’s sector of the Sahara finds of minerals at Tindouf are expected to produce 50 per cent iron.

The following figures, taken from UN Statistical Year-books, illustrate the great rise in output of minerals in Africa in the post-war period:

The highest rate of increase is in South Africa, where a production of 624,108 kg. of gold makes the Republic the producer of half the world’s supplies. An output of 2,838,000 carats of diamonds in 1959, about 40 per cent of which were gem stones, puts it third after the Congo and Ghana, whose output is almost entirely of industrial diamonds, though the value received, because of its control of the industry and the number of gem diamonds, is relatively greater than that of Ghana’s. She also leads in the production of chromium ore and is second in the output of lead from S. W. Africa. Even South Africa’s uranium production of 7,000 tons, obtained largely from gold and copper slimes, is way ahead of the Congo’s 1,761 tons.

Mining of all kinds in South Africa has reached a stage of exploitation which can be compared with that of Canada, and which is now feverishly beginning to open up in Australia, where the same companies, in alliance with American and other associated interests, are paramount. The close relationship borne out even in the names of mines, particularly in Canada, which frequently duplicate those also to be found in South Africa and the Rhodesias.

Africa’s possession of industrial raw materials could, if used for her own development, place her among the most modernised continents of the world without recourse to outside sources. Iron ore, mostly of high quality, is to be found in gigantic quantities near to the coast where it can easily be shipped abroad. As for bauxite, Africa’s estimated reserves are more than two-fifths those of the whole world. They are twice those of Australia, which are placed second. Guinea alone is estimated to contain deposits equal to those of the whole of Australia, that is, over 1,000 million tons. Ghana is said to have reserves totalling 400 million tons. Sudan, Cameroun, Congo and Malawi are other known sources of considerable deposits, and the investigation of probable reserves is proceeding in Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Portuguese Guinea and in other parts of Africa.

Among the base materials essential for the production of iron and steel, manganese has a place of high importance. Besides being used for alloying with pig iron in the manufacture of special steels, it is used in the chemical industry. For certain purposes, under present-day processes, manganese is irreplaceable. It is in constant use at the rate of 18 to 20 kg. to a ton of steel. The Soviet Union and China are practically self-sufficient in the supply of this essential basic material. The other great world steel producers, the United States, Western Europe and Japan, do not have appreciable quantities in their own territories. Their principal sources of supply are Africa, India and Brazil. Of these Africa provides the greatest quantity. Angola, Bechuanaland, Congo, Ghana, Morocco, Rhodesia, South-West Africa and Egypt have been among the producing countries for some time. Others, like the Ivory Coast and Gabon, are now being added to the list.

North Africa is the world’s greatest producer of phosphates. Morocco alone exports seven million tons out of some nine million tons coming from North Africa. The U.S.A. comes next, with an export of four million tons. New producing countries which have appeared since 1957 are China, with some 600,000 tons in 1960, and North Vietnam with 500,000 tons. Senegal is a producers of aluminium phosphate, her output being about 90,000 tons a year, and Togo is now appearing on the phosphate market.

Iron ore, like oil, has become one of the more recent mineral discoveries in Africa, North and West Africa being the main centres. Among high-grade ore producers in 1960 were Liberia (68 per cent iron content), Angola (65 per cent), South Africa (62 per cent), Sierra Leone (60 per cent), Morocco (60 per cent), and Rhodesia (55 per cent, the minimum iron content for high-grade ore). There have been discoveries of higher quantities and quality since 1960. It is considered that most countries in West Africa, from Mauritania to Congo (Brazzaville) have iron ore deposits. Enlargement of the production in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone is being planned. Deposits are either being placed under production or are planned for exploitation in Nigeria, Niger, Mauritania, Ghana, Gabon, Cameroun, Senegal and Congo (Brazzaville). Ghana’s reserves, estimated at about a million tons, are in the Shiene area of the Northern Region, and are not easily accessible, and have an average iron content of 46 to 51 per cent. It is proposed to exploit the deposits for domestic use when the Volta lake is opened up for inland transport. The Niger Republic deposits are estimated at more than 100 million tons of 45 to 60 per cent quality. They are at Say, about thirty-five miles from Niamey, at the moment distant from roads, railways and ports. These disadvantages affect also the exploitation of the known deposits in the Kandi region of Dahomey, of 68 per cent quality. Algeria has been an iron ore producer for some time. Exploitation was undertaken there in 1913 by a French enterprise known as La Société de l'Ouenza, operating at Djebel Ouenza in the south of Constantine, close to the Tunisian border, formerly incorporated as a department of France. The company has built its own railway lines connecting its two producing centres to Oued-Keberit, to join with the Bone-Tebessa line. Its plants enable Société de l'Ouenza to export iron principally to Great Britain, Germany, Italy, Belgium and the Low Countries, and the U.S.A. Between the outset of this exploitation and the end of 1960, a total of 46 million tons of mineral has been extracted. Ouenza’s personnel then included 600 European and 1,500 Algerians.

The existence of iron ore in the Sahara was first indicated in the Gara Djebilet region, some 110 miles south-east of Tindouf, in 1952. Difficulties of situation and water supply are obstacles in the way of exploitation. Nevertheless, a committee composed of representatives of the iron and steel industries of France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands is busily investigating the possibilities, in conjunction with the French Bureau d'Investissements en Afrique. Liberia’s iron ore resources are reputed to stand at 1,000 million tons in the Nimba range and 600 million tons in the deposits near the Sierra Leone border. The Nimba iron ore mine which has been sunk and is being mined by a consortium known as LAMCO Join Venture Enterprise (members of the consortium being LIberian-American-Swedish Minerals Company and Bethlehem Steel Corporation) is estimated to have reserves of over 300 million tons of high-grade hematite ore with an average iron content of over 65 per cent. Long-term contracts are in hand from German, French, Italian and Belgian steelworks, while a considerable part of the output will go to the powerful United States Bethlehem Steel, which has a 25 per cent participation in the venture, the other 75 per cent being taken up by LAMCO. LAMCO is said to be a company shared between the Liberian Government and foreign enterprise on a fifty-fifty basis. The non-Government participant is Liberian Iron Ore Company, a consortium of American and Swedish financial and steel interests.

Chief of these is the Swedish mining company, Grangesberg, which besides having an important stake in the LAMCO Nimba mine acts as managing agent for this joint venture, in which American capital predominates. Grangesberg, formerly holding 12/28 of the LAMCO syndicate, according to its annual report adopted at its annual general meeting held at Stockholm, on 18 May 1962, increased its participation to 15/28, giving it a majority slice of the equity.

Grangesberg owns iron ore mines in Central Sweden, as well as power stations, forest and farm properties. It also built and controls the Frovi-Ludviks Jarnvag railway undertaking, and operates the Oxelsund Ironworks, turning out pig iron and heavy plates. In addition it possesses and runs a fleet of ships which, at the end of 1961, comprised thirty-three vessels, and had on order another four for delivery in 1962 and 1963. A subsidiary, Aktiebolaget Hematit, works mines in North Africa, and others include an arms and chemical enterprise, Aktiebolaget Express-Dynamit. The Swedish Government took over holdings which Grangesberg exercised in Luossavaara-Kürunavaara AB – LKAB, but out of the purchase price of Kr. 925 million it received, the company reinvested Kr. 100 million in LKAB.

The value given to these Government-purchased holdings was almost twice as much as Grangesberg’s fully paid-up capital of Kr. 495,800,000, and even without them its assets at the end of 1961 stood at Kr. 403,719,000 in addition to shares in subsidiary and other companies totalling Kr. 154,380,000. The company’s net profit for the year was Kr. 38,787,251 and dividends absorbed very nearly the same amount at Kr. 35,700,000. Its iron sales increased from 1,620,000 tons in 1959 to 2,560,000 tons in 1961.

Bethlehem Steel is a heavy investment sphere for Rockefeller’s profits from Standard Oil, which has been pushing to displace British-Dutch oil interests in the Far East. John D. Rockefeller the Third has made himself a specialist on the Far East, with a preference for Japan, where he was a member of John Foster Dulles’ peace treaty mission in 1951. He established the Japan Society Inc. for cultural inter-change. Persistent visits and pressure have boosted Standard Oil Company’s facilities in Japan, Indonesia, New Guinea and India in oil production, refining and sales. The Rockefeller interest in Japan is reflected in the link with the Sumitomo metallurgical group, which has been cemented in the Bethlehem Copper Corporation Ltd., a 1955 British Columbia (Canada) registration. Property claims in the Highland Valley of British Columbia hold ore reserves of 3,304,000 tons grade 1·20 per cent copper and 12,723,000 tons of 0·82 per cent grade. Additional claims are held in the provinces as well as a full subsidiary, Highland Valley Smelting and Refining Co.

Total output is to go to Sumitomo Metal Mining Co. Ltd. group, which is responsible for bringing the property into production. It has bought 400,000 shares in Bethlehem and has options on further lots in connection with loan promises of $5 million and an agreement to contribute one half of the funds required for expansion. Sumitomo provides Bethlehem’s vice-president and two other directors, one of whom is from the prominent Tanaka family. The first deliveries from the Nimba mine were made during May 1963 and production of 7,500,000 tons is planned for 1965.

The Nimba iron ore streaks of Liberia stretch into Guinea where prospecting is taking place in the Nimba-Simandou region, about a thousand kilometres from Conakry, close to the Liberia-Ivory Coast borders. A West European banking group representing itself as the Consortium Européen pour le Developpement des Ressources Naturelles de l'Afrique – CONSAFRIQUE – is undertaking investigations by contract with the Guinea Government. The group comprises:

Banque de l'Indochine, Paris.

Deutsche Bank A.G., Frankfurt/Main.

Hambros Bank, London.

Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij N.V., Amsterdam.

Société de Bruxelles pour la Finance et l'Industrie – BRUFINA – Brussels.

S.A. Auxiliaire de Finance et de Commerce – AUXIFI – Brussels.

Compagnie Franco-Americaine des Metaux et des Minerais – COFRAMET – Paris.

The Banque de l'Indochine is closely associated with the Banque de Paris et des Pays Bas, and has links with the Société Générale de Belgique. Its original sphere of operations has been largely closed by its exclusion from North Vietnam because of the socialist regime established there, while in South Vietnam it has now become subordinate to American finance. The Banque de l'Indochine, which already had a foothold in Algeria, is turning more and more to Africa, where it is grouped in several consortia, usually round the interests connected with the Société Générale de Belgique, the Banque de Paris et des Pays Bas and the Deutsche Bank, all leagued with Morgan international interests. The Banque de l'Indochine is represented on the board of Le Nickel, which exploits a variety of minerals in Asia and Oceania and has a substantial interest in Compagnie Francaise des Minerais de l'Uranium. The late H. Robiliart was another director on Le Nickel’s board, as well as J. Puerarai from Penarroya and Les Mines de Huaron, whose former president was the late H. Lafond of the Banque de Paris et des Pays Bas. These and other allied French and American interests, grouped around the Société des Minerais et Metaux, Patino and American Metal Climax form the combination known as COFRAMET, several of whom received Marshall Plan credits in the post-war years.

The Deutsche Bank, which has always concerned itself with exploitation investment in the less developed areas, also has close associations with the Banque de Paris. Even during the war the Deutsche Bank did not relinquish its role of colonialist exploiter, but followed the German army into the conquered territories of Europe. Today it is busy pushing West German interests in Africa, Panama, Chile, Pakistan, Columbia and Puerto Rico. It has floated loans for Argentina, the City of Oslo and Norway. It has a holding in the Pakistan Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation Ltd. It has acted as fiduciary house for such considerable international corporations as General Motors, Philips, Royal Dutch Petroleum and Snia Viscosa. The connection with Royal Dutch Petroleum continues Deutsche Bank’s association with the pre-first world war Mosul oil concession in the part of Turkey that became Iraq, while its activities on behalf of General Motors and Philips emphasise the subservient role the Deutsche Bank plays to the Morgan interests which conduct the international expansion of these vast ramified organisations. On the board of this bank sit directors of the Mannesmann steel interests of the Ruhr, also represented on another German bank, the Dresdner, which is also engaged in a number of investment ventures in Africa.

The Mannesmann steel company, one of the most important in the German Ruhr, was established in 1885. Its chairman, Dr Wilhelm Zangr, is a director of Algoma Steel Corporation Ltd. of Canada, in which the German interests were linked for some time with the Hawker Siddeley group of Great Britain. Mannesmann is associated in several projects in India and elsewhere with Krupps and its Duisberg affiliate Demag. A. G. Demag works in close collaboration with the American firm of Blaw Knox & Co. This firm which makes equipment for steel mills and for chemical, petroleum and other industries falls within the Mellon sphere of interests. Hence it has links with Bethlehem Steel, which associates with the West German Steel industry, into which the Mellon interests have increasingly pushed. Both the Deutsche Bank and Dresdner Bank, with which Mannesmann is so closely tied, in alliance with the Morgan Guaranty Trust, have considerable interests in the Oppenheimer companies of southern Africa.

Hambros Bank (the late Sir Charles Hambro was the link with the Bank of England), Cable & Wireless (Holding) and Oppenheimer holding companies have valuable interests in the diamond, gold and other mining undertakings in Central and Southern Africa. A merchant bank, Hambros has long been associated with the Scandinavian investment market, and has in the past years spread its activities in Europe in anticipation of Britain’s entry into the Common Market. It added a subsidiary in Zurich in 1962, Hambros Investment Company. Like many other financial institutions it has entered a growing field for financial investment, that of leasing equipment to industry. For this purpose Hambros established Equipment Leasing Company (Elco) in 1962. It also engages directly in the business of importation and distribution of motor cars and commercial vehicles from the British Motor Corporation into the United States, through British Motor Corporation-Hambros Inc., a joint fifty-fifty venture. The British Motor Corporation covers Austin, M. G., Morris, Riley, Wolseley motors and subsidiary companies of the Nuffield and other groups. Through its acquisition of the banking firm of Laidlaw & Co., New York, Hambros is strengthening its associations with important American banking interests. Among Hambros Bank’s many other interests is its connection with the bullion firm of Mocatta & Goldsmid, which increased its holdings of bullion in 1961 from £3,750,000 to £6,500,000.

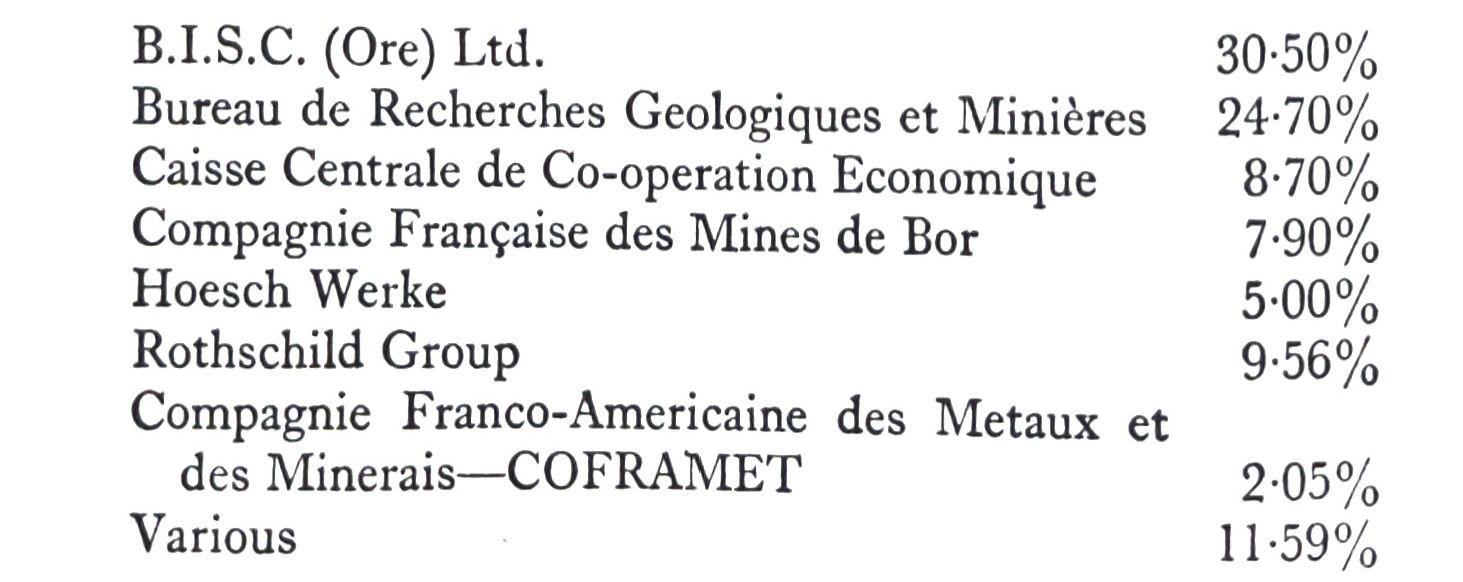

Another financial-industrial group, headed by the British company, B.I.S.C. (Ore) Ltd., and including French, German and American financial participants, is already working iron ore deposits in Guinea at Kaloum, in immediate proximity to the port of Conakry. These deposits of 50-55 per cent grade ore were discovered in 1904, when construction of the railway line from Conakry to Niger was begun. Prospecting was carried out between 1919 and 1922 by the Mining Company of French Guinea. In 1948 a new company was formed to confirm previous findings. This was the Compagnie Minière de Conakry, whose plant at Kaloum is geared to an annual production of 1,200,000 tons, which can be doubled without any appreciable modifications of the set-up. Alongside its iron production, this company is multiplying its income from the establishment of a complex of industries which includes the manufacture of explosives by the L'Union Chimique de l'Ouest Africain – UCOA. Participation in the Compagnie MInière de Conakry, which is capitalised at 1,500 million Guinea francs, is as follows:

Hoesch Werke is a leading West German iron and steel firm, associated with the larger combines like Mannesmann and Phoenix-Rheinruhr, the last of which has lately effected a fusion with the Thyssen group. Before the last war Thyssen was associated with Krupp.

The West German iron and steel industry is looking increasingly for raw materials supplies for use in German plants. In other parts of the world where less developed countries are making an attempt to industrialise, they are setting up transformation foundries and rolling mills to bring secondary and intermediate stages ores brought in from mines to which they have been granted concessions. Thus the Mannesmann affiliate in Brazil, Companhia Siderurgica Mannesmann, is to achieve a crude steel capacity of 300,000 tons from iron ores from its mines less than five miles from a new blast furnace it is erecting at Belo Horizonte. American capital has large holdings in the German iron and steel industry, in some cases a controlling one, achieved during the post-war American occupation of Western Germany.

The Morgan banks led this incursion into the West German and other European heavy industry fields, using their European agents and associates in Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Belgium and Switzerland for the purpose. Among these associates is the multiple Rothschild group, already flanking the Morgans in their Southern African ventures. The British section, headed by N. M. Rothschild, has, in the words of one commentator, the Hon. Peter Montefiore Samuel, a member of the London merchant banking house of M. Samuel & Co. Ltd., ‘re-established their ancient connections with de Rothschild Frères’, which go back to the pre-Napoleonic days. The firm of M. Samuel is itself linked with the Banque Lambert of Belgium and the Banque de Paris et des Pays Bas of France, all within the investment sphere of the Société Générale de Belgique, in an investment consortium established to exploit the European Common Market. Edmund L. de Rothschild and the Hon. P. M. Samuel sit together on the board of Anglo Israel Securities Ltd. De Rothschild, a director of two insurance companies, the Alliance and Sun Alliance created by the Rothschilds, sits also on the board of the British Newfoundland Corporation, incorporated in Canada, which secured 7,000 square miles of concessionary mineral lands and an additional like extent of oil and gas concessions from the Newfoundland Government, in 1953. The corporation also holds concessions on 35,000 square miles in Labrado. The same de Rothschild further adorns the board of Five Arrows Securities Co. Ltd., of Toronto, in which Barclays Bank and Morgan associates are interested. The Hon. P. M. Samuel is a director of the Shell Oil holding company, Shell Transport & Trading Co. Ltd., as well as of other investment companies, including several operating in Central Africa, such as Heywood Investments Central Africa (Pvt.) Ltd., on which he is joined by another member of the family, the Hon. Anthony Gerald Rothschild, who also sits on the boards of other such concerns, as well as of publishing and publicity firms.

B.I.S.C. (Ore) Ltd. is also included in a consortium, Société Anonyme des Mines de Fer de Mauritanie – MIFERMA – exploiting iron ore at Fort Gouraud, Mauritania. It is estimated that there is a minimum of 100 million tons of high-grade ore of 64-65 per cent iron contained in this property on the western edge of the Sahara Desert, and it is being prepared to produce an annual output of six million tons. The British group as well as German and Italian groups have substantial holdings, but the major interest is held by a French group headed by the Bureau Minière de France d'Outre Mer. The following are the participants in this venture:

B.I.S.C. (Ore) Ltd.

British Ore Investment Corporation Ltd.

British Steel Corporation Ltd.

Compagnie du Chemin de Fer du Nord.

Compagnie Financière pour l'Outremer – COFIMER.

Denain-Anxain.

Republique Islamique de Mauritanie.

Societa FInanciara Siderurgica – FINSIDER.

Societa Mineraria Siderurgica – FERROMIN.

Union Siderurgique du Nord de la France – USINOR.

The company has been capitalised at 13,300 million francs CFA, and has the following affiliates:

Société d'Acconage et de Manutention en Mauritanie –

SAMMA (capital: 100,000 francs CFA).

Société Anonyme d'Hebergement en Mauritanie –

HEBERMA (capital: 25,000,000 francs CFA).

Société Anonyme de Transports Mauritaniens –

SOTRAM (capital: 50,000,000 francs CFA).

And to prove that though the names may change the components remain the same, the management of the mine will be in charge of Penarroya.

Finsider is the financing organisation related with the industrial group comprising Ferromin; and the Deutsche Bank was concerned with certain share introductions made by it during 1961-2. The Compagnie du Chemin de Fer du Nord comes within the influence of the Banque de Paris et des Pays Bas, as does Union Siderurgique du Nord de la France.

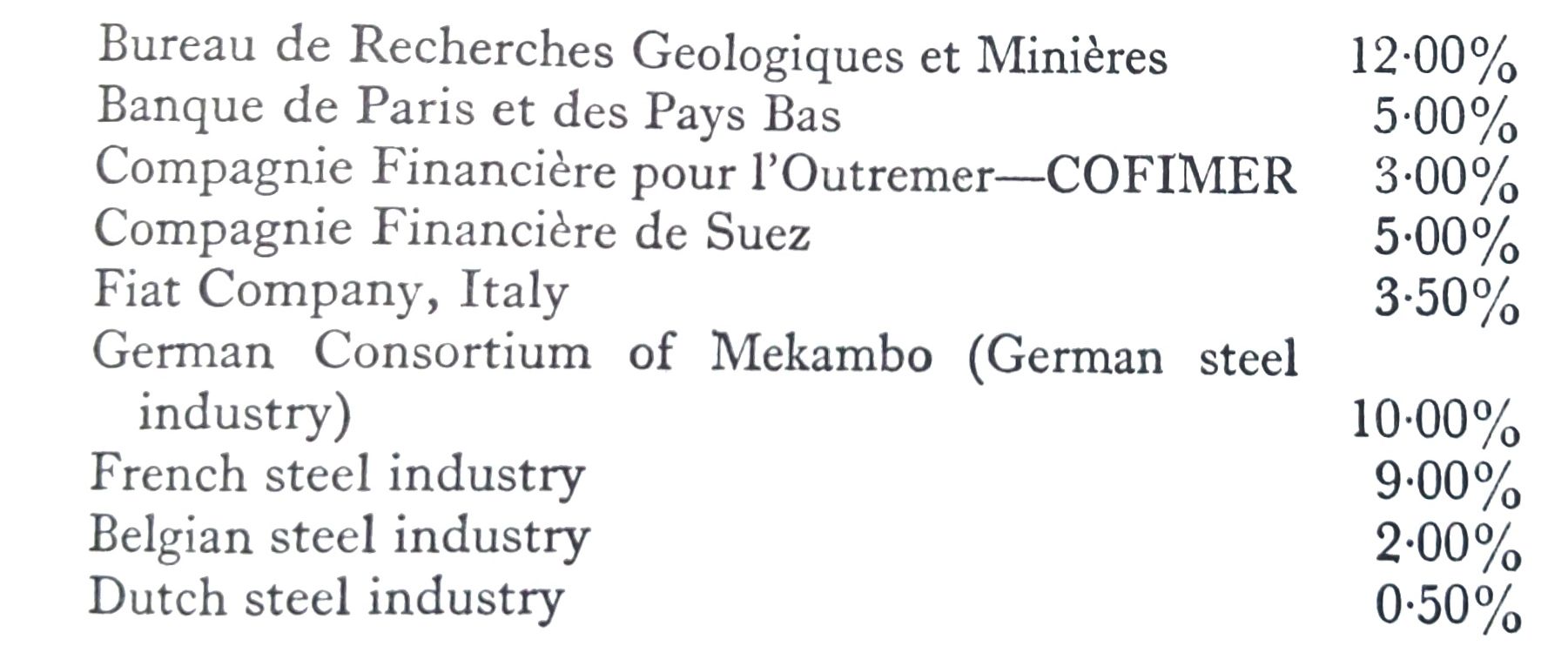

Gabon, whose timber has hitherto been its main export, has shown signs of possessing iron ore deposits since 1895. Investigations were carried out from 1938 by what was then the French Overseas Mining Bureau, transferred later to the Bureau de Recherches Geologiques et Minières, and joined by the Bethlehem Steel Company. The resultant company, Société des Mines de Fer de Mekambo, was established in 1955, with the major purpose of ‘creating a great centre of production capable of satisfying, at long term, a part of the anticipated needs of Western Europe’s steel industry and the future requirements of Bethlehem Steel’. Thus, in the participation, Bethlehem Steel has a 50 per cent holding. The other parties to the undertaking are:

The undertaking is capitalised at 200 million francs CFA, and on its behalf further investigations have been undertaken by the syndicate grouped round the Bureau de Recherches and the European Coal and Steel Community, underlining the interest that the European Community and its Common Market has in Africa’s primary resources. What makes Gabon’s iron ore deposits so interesting is their proximity to important electrical power resources, capable of affording abundant electricity at an estimated rate of one franc CFA per kilowatt.

Fiat’s inclusion in this consortium is an illustration of the inevitability of monopoly’s extension into capital investment in less developed countries. Fiat is not simply an automobile producing company, but a vast industrial organisation which has penetrated deeply into financial investment in Europe and beyond. Founded in Turin in 1899, Fiat has grown in sixty-three years into the second-largest motor manufacturer in Europe and the fourth largest in the world after General Motors, Ford and Vollkswagen. If Simca, which is linked with Fiat, is added to Fiat’s production, it is larger than that of Volkswagen. But Fiat’s growth came, not through automobile manufacturing, but through industrial production connected with armaments during the first world war, its expansion continuing in the second world war. It made profit out of the devastation that came to Italy and continued to build itself up in the post-war period under its founder, an ex-cavalry officer of a well-to-do Turin family, Giovanni Agnelli, in whom ‘business genius was combined with the ruthlessness of an American railroad or oil tycoon of the old days’.

In its working year of 1960 the Fiat company had investments in other companies valued at some £26,700,000, a valuation decided by the company, since under Italian company law this is left entirely to ‘the discretion of the company’s accountants, and figures listed in Italian balance sheets under this heading usually bear no relation whatsoever to the market value or even to the face value of the equities and bonds held’. Cement, camera and film manufacture are among the company’s ventures. A subsidiary, Unione Cementi Marchino, produces 16 million tons of cement yearly. The Cinzano vermouth which is so widely enjoyed throughout the world is among Fiat’s undertakings. Its subsidiary, Impresit, is busy wherever hydro-electrical dams are being constructed. It built the Kariba dam in Rhodesia and is working on Ghana’s Volta dam. Fiat owns property all over the world. Practically the whole of the Rue Blanche in Paris’s notorious night-life world is owned by Fiat, as well as land, hotels and pleasure facilities in Sestriere, a leading Italian winter sports resort.

Like so many of the monopoly organisations that spread their interests over the globe and into manifold undertakings, Fiat has branched into oil, having a 22 per cent holding in Aquila, the Italian subsidiary of the Compagnie Française des Petroles. Aquila is now operating in Austria as well as Italy. Shipping also comes within Fiat’s operational sweep through ownership of a couple of shipping companies. All of these ramifications, which cover more than a hundred companies inside and outside Italy, are almost all vested in the holding company, Instituto Financiario Industriale, found in 1927, and known briefly as J.F.I. In the latter part of 1962 Fiat joined the international group comprising S.A.B.C.A. – Avions Fairey (Belgium), Breguet (France), Focke-Wulf (Germany), Fokker (Holland), Hawker Siddeley Aviation (U.K.) and Republic Aviation (U.S.A.), which submitted designs to NATO for a vertical take-off strike aircraft. Fiat had already maintained co-operation with Bristol Siddeley in the manufacture of Bristol Siddeley Orpheus turbo-jet engines for the G.91, then the standard NATO strike aircraft. And to help mould public opinion in the right direction, Fiat published Italy’s second largest daily paper, La Stampa.

Compagnie Financière de Suez was in considerable difficulty after the affairs of the Suez Canal were taken over by the Egyptian Government, following the unsuccessful attempt by Anglo-French imperialism to dominate Egypt once more, and has been under pressure from its shareholders. However, the board held off the shareholders and righted its position by looking for investments which will give quick high returns. It has made certain equity purchases in Australia, but is really seeking quick profitability in Saharan oil and African primary materials. Its investment in Coparex is expected to give early good results, since this company had in 1961 large reserves of oil from which it was deriving a substantial income.

Bauxite in Western and Equatorial Africa is even more plentiful than iron ore, but its exploitation is waiting upon the availability of electrical power. We have already referred to FRIA, the enterprise that has been set up in the Republic of Guinea by the consortium with the Rockefeller firm of Olin Mathieson at its head. The second largest holding in this group is held by Pechiney-Ugine. These same groups, together with Reynolds, Kaiser and Mellon’s Alcan, formed another enterprise, Les Bauxites du Midi, which originally exploited other deposits at Kassa and Boke. Notice, however, was given to the company by the Guinea Government that if, within three months from 24 November 1961 Bauxites du Midi had not made arrangements to set up an aluminium factory at Boke by July 1964, as originally agreed, its installations, works and machinery would be expropriated, as well as its assets, for which reparation would be made. The Guinea Government declared that it waited for the company to renounce ‘its colonial methods based on the simple extraction of minerals whose transformation would be subsequently effected outside the country of production’.

Pechiney-Ugine is also concerned with the Compagnie Camerounaise d'Aluminium Pechiney-Ugine – ALUCAM – in which a 10 per cent participation is held by Cobeal, a Société Générale de Belgique affiliate. Pechiney-Ugine’s share of Alucam’s total production in 1962 of 52,246 tons was 46,443 tons, obviously the most important.

Gabon’s natural resources are proving immensely rich. Atomic energy commissions are busy prospecting and investigating uranium sources at Mounana in the Haut-Ogooue region, one of the most isolated in the country. The only means of access is the river Ogooue, cut by rapids over more than 600 km. of its length. At the beginning of 1959, however, a 100-km. road, constructed by the Compagnie Minière de l'Ogooue – COMILOG – put the terminus of the railway which opened in 1962 about 120 km. from Mounana, thus making it more accessible. The ore is to be mined and uranated by the Compagnie des Mines d'Uranium de Franceville, capitalised at 1,000 million francs CFA. A participant in Comilog, the Compagnie de Mokta, is responsible for the management of the mine. Comilog is exploiting Gabon’s manganese deposits at Franceville, which were first investigated by the French Overseas Mining Bureau in collaboration with U.S. Steel, the mammoth American steel firm, controlled by Morgan interests. Together with its affiliates, U.S. Steel has 49 per cent control of Comilog, to which the other parties are the frequently-present Bureau de Recherches Geologiques et Minières (22 per cent), the Compagnie de Mokta (14 per cent) and the Société Auxiliaire du Manganese de Franceville (15 per cent). The enterprise is capitalised at 2,500,000 francs CFA. United States and French monopolists are the chief parties to Comilog.

Comilog has as its principal shareholder (49 per cent) the largest steel outfit in America, and hence the world, U.S. Steel, ‘a perfectly integrated iron and steel concern’. The manganese bed on which Comilog is working at Franceville in Gabon is one of the most important in the world, with estimated reserves of 200 million tons of 50 per cent ore. The French Cie de Mokta has a 19 per cent interest and, besides being concerned in operating directly the Grand Lahou manganese mine on the Ivory Coast, controls important production of iron, manganese and uranium ores through holdings in Algeria, Spain, Tunisia, Morocco and Gabon. It has, for instance, 40 per cent in the Cie des Mines d'Uranium de Franceville, which is developing the rich uranium mine at Mounana, Gabon. De Mokta is linked directly and by associates with interests radiating from Anglo-American Corporation and the great iron and steel trust of ARBED.

U.S. Steel and General Electric are world giants in their related spheres. The first, by virtue of its multiple divisions covering all aspects of the steel industry, is the sixth largest industrial company in the United States; the second is the leading producer of electrical equipment and appliances in the world, with affiliates, subsidiaries and associates all over the globe. Its plants affect many sectors of industry: radio, aviation, marine, scientific research, and turn out heavy capital goods, industrial components and materials and defence products, as well as consumer goods. U.S. Steel was founded in 1901 by J. Pierpont Morgan as a holding company controlling over half the American steel industry. Since then the American steel industry has expanded by giant strides and other commanding trusts have forged ahead. But U.S. Steel leads still and today controls 30 per cent of America’s steel and cement production. On the board of General Electric sits Henry S. Morgan, so that it is not difficult to find the relationship between this international monopoly and U.S. Steel in the exploitation of some of Africa’s richest resources to feed the military as well as economic demands of the world’s most dangerous imperialism. Operating universally, its interests are located at every crisis point of the globe.

It is said that as a result of the most complicated transaction, Tanganyika Concessions ceded to an American financial group closely associated with the leading United States banking houses 1,600,000 of its shares, as a result of which the American group probably has a majority in this British Company which owns 21 per cent of the shares of Union Minière, whose empire is the Congo. [France Observateur, 9 July 1964.] American interest in the Congo is motivated by very substantial investments, frequently hidden behind British, French, Belgian and West German cover, and engaging leading personalities in United States political affairs, Mr Adlai Stevenson, for instance, representing his government at U.N.O., presided over the firm of Tempelsman & Son, specialists in exploiting Congo diamonds; and Mr Arthur H. Dean, who leads America’s delegations to disarmament conferences, was vice-president and still is a director of American Metal Climax, a huge consumer of uranium, since it provides 10 per cent of United States production. American Metal, according to an information blurb, forms with its subsidiaries ‘a powerful international mining group, which includes, notably, Rhodesian Selection Trust Ltd.’.

The NATO powers are interested in Gabon because of her riches. At present American OFFSHORE International has been offered a drilling contract for Société de Petrol Afrique Equatorial (SPAFE) with headquarters in Port Gentil. This company employs over 1,200 Africans who are all subordinate to the over 400 white people. There is no oil refinery at present in Gabon, but Gabon, Chad, Congo, Brazzaville, Central African Republic and Cameroun have agreed to establish a refinery to be financed by their respective governments and France. The first meeting of the representatives of these governments was on 22 July 1964 in Port Gentil. According to the Minister the necessary investigations are going on to start the refinery before the end of 1965. There are, I was told, many oil finds both in the territorial waters of Gabon and deep in the interior in large economic quantities to supply many parts of Africa. My information is that all the petroleum companies now distributing oil in French-speaking Africa have controlling shares in the oil production company in Gabon. Agip is not allowed to hold shares in the company. Readers will recall what caused the downfall of Mr Adoula in the Congo – oil politics. It seems to me, therefore, that two economic issues will influence the duration of French occupational forces in Gabon for many years, namely uranium and oil.

It is quite likely that Africa could provide enough phosphates not only to fertilise the abundant agricultural production that would cover its future food and industrial requirements, but to leave enough over to supply the needs of many other parts of the globe. At the moment important centres of phosphates are the Djebel-Onk deposits in Algeria, those at Taiba in Senegal, at Lac Togo in the Republic of Togo, and at Khouribga and Youssoufia in Morocco.

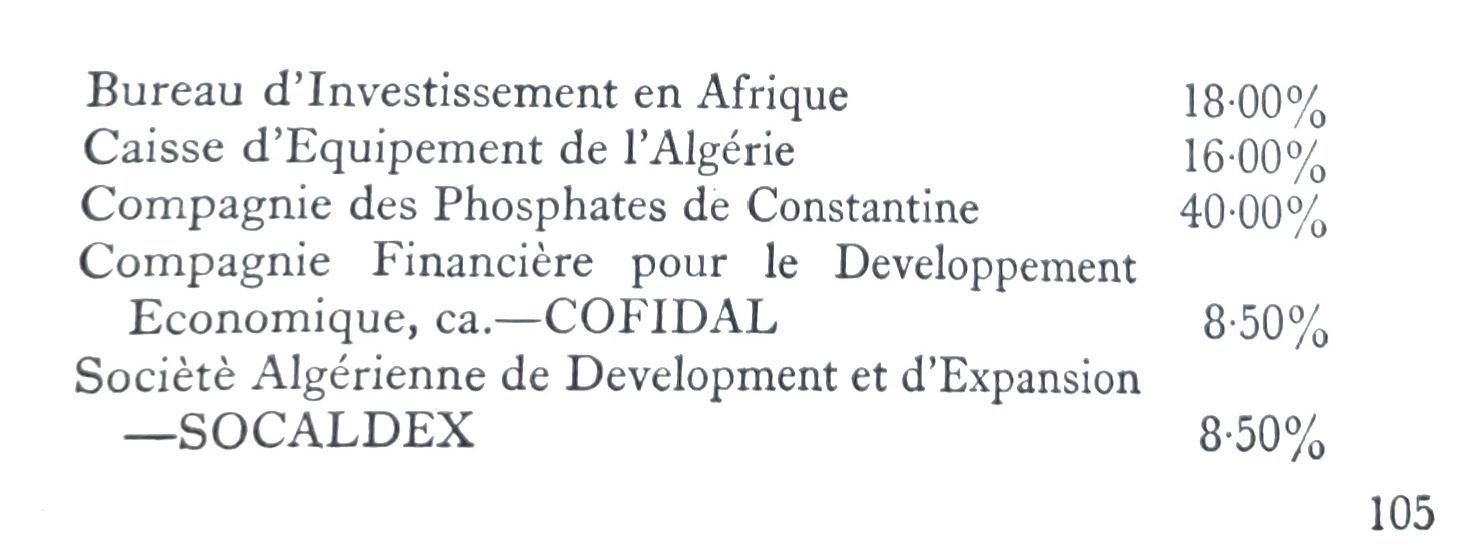

The Société de Djebel-Onk, with a capital of 30 million new francs, comprises the following interests:

The Compagnie Senegalaise des Phosphates de Taiba finds the Government of Senegal associating with the Bureau de Recherches Geologiques et Minières, Pechiney, Pierrefitte, Compagnie des Phosphates de Constantine, Compagnie des Phosphates d'Oceanie, Cofimer and the Société Auxon. The same group, headed by the Banque de Paris et des Pays Bas and the French interests which it represents made an agreement in February 1963, under the signature of the bank’s director-general, J. J. Reyre, with the International Minerals & Chemicals Corporation, by which the latter became a partner in the consortium which is exploiting what is said to be the world’s largest high-grade phosphate mine, near Dakar. There are several things that are noteworthy in this arrangement.

First of all, there is something distinctly ominous in an agreement between two foreign combinations, one of which is a participant in a company associated with the State whose raw materials it is exploiting. It accentuates the contemptuous attitude towards the host country implicit in the monopoly’s purpose. International Minerals is the foremost producer of phosphate and phosphate agricultural products in the North American continent, with extensive phosphate mining and chemical processing operations in Florida, U.S.A. It also owns a potash mine at Carlsbad, New Mexico, and another $10 million potash project in Canada. It has a market for its products throughout the Americas and Western Europe. For the Senegalese Government this phosphate mining project, which is to have an output of 500,000 tons a year, has an important place in its four-year plan. It is intended to broaden and develop the economy. However, the purpose of the monopolies controlling the venture is entirely otherwise. ‘This partnership bolsters our world position in regard to strategic phosphate reserves,’ Mr Reyre is reported to have said on signing the partnership agreement the International Minerals (West Africa, 17 February 1962).

Phosphates deposits were uncovered in Togo about eighteen miles from the sea in 1952. Investigations had been going on since 1884 by French and British interests. It was a geological adviser of the Comptoir des Phosphates de l'Afrique du Nord who found in the Akoumape region indications of very important deposits of first quality which extend across Lake Togo. The Republic of Togo has associated itself with the Compagnie Togolaise des Mines de Benin, which is exploiting the deposits, and comprises the interests already engaged in monopolising other phosphate resources in Africa. These are the Compagnie Constantine, Penarroya, Cofimer, the Banque de Paris, Pierrefitte and the Compagnie Internationale d'Armement Maritime Industrielle et Commerciale. Capital is 1,180 million francs CFA. The first shipments were made in September 1961, when they left the new wharf of Kpeme for the United States and American-controlled plants in Japan. The plan is to produce initially 750,000 tons of concentrate yearly, a level it is intended to raise progressively to a million tons if the market possibilities are there.

There would be no lack of market possibilities if fertilisers were made available to the developing countries at prices which their purchasing power could afford. As it is, the competition in fertilisers from America and other sources is extremely keen, and the British producers, of whom Fison Ltd. and I.C.I. and Shell practically monopolise the trade in the United Kingdom, were the subject of investigation by the British Monopolies Commission in 1959. Fertilisers in the U.K. have been kept at a subsidised price level that led to serious complaints of overcharging. Fison holds 40 per cent of the U.K. market, and it has now entered into an agreement with I.C.I., whereby it will be supplied by the latter with ammonia from their new Immingham plant. This will cut costs in an effort to meet shareholders’ complaints of diminishing profits.

This co-operation of the largest producers of fertilisers is going on in order to monopolise raw materials’ supplies and markets, so as to sustain prices that will yield higher profits on the considerable investments involved. The chairman of I.C.I’s Billingham Division said the company’s steam naphtha process has completely transformed the economics of ammonia production and has put the company in the position of being a world producer of ammonia, not just a U.K. producer.

Transportation is an important factor in the cost of fertilisers, and it is easy to appreciate that if phosphates from Africa are taken to Europe for working up and then returned in fertiliser form to Africa, packed in bags, prices cannot be economic for African agriculture. In this connection it is interesting to note that Fison have established in India, in association with the leading iron and steel firm of Tata, a fertiliser producing company, Tata-Fison Ltd., which Sir Clavering Fison, the U.K. Company’s chairman, has described as now being the largest company in the industry. Fison has a partnership in Albatros Super-fosfaatbrieken N.V., of Utrecht, Holland, with which company it established fertiliser and chemical companies in South Africa. During their financial year 1961-2 the Fison-Albatros company admitted into its South African affiliate, Fisons (Pty) Ltd., a local banking undertaking, Federale Volksbeleggings Beperk, which made enough funds available to allow the South African Fison company to enter upon the exploitation of phosphate deposits at Phalaborwa in the Transvaal. Fison has other companies in South Africa concerned with agricultural chemicals and pharmaceuticals. All these companies did well during the 1961-2 year, according to Fison’s chairman, who added that ‘despite the difficult conditions in East Africa and the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, our companies there have maintained their position and earned satisfactory profits’. Its subsidiary in Sudan, Fisons Pest Control (Sudan) Ltd., sprayed a record cotton acreage of over one million acres and achieved profits found satisfactory by the chairman.

Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Malaya and Nigeria are all countries in which Fison have established companies for the expansion of their fertiliser and agricultural chemical markets, and they have recently begun to extend into South America and Pakistan. Plants for the manufacture of fertilisers have been erected at Zandvoorde, in Belgium, jointly with Union Chimique Belge S.A. Besides fertilisers and related chemicals manufacture, horticulture and scientific apparatus production, Fison are in the food processing and canning firm of John Brown Ltd. ‘for the purpose of selling chemical know-how and plants to the U.S.S.R.’.

Oil and gas, which are becoming more and more important finds in Africa, particularly in the Sahara, are drawing the feverish competition of the predominant financial and industrial interests that are bringing monopoly into a tighter and tighter ring. Even smaller ones are pushing into this field, which, while it calls for extremely heavy initial capital for prospecting and sounding, offers the fabulous profits that have built up the fortunes of Standard Oil and Mobil-Socony for the Rockefellers, Gulf Oil for the mellons, Continental Oil and Dutch-Shell for the Morgans, Texaco for the Chicago group, Hanover Bank and others. Tennessee Corporation, the Guggenheimer multiple enterprise operating nitrate and copper concessions in South America and holdings in the Congo and other parts of Africa, has extended its interests beyond uranium, fertilisers and chemicals into oil. Its Delaware subsidiary, Tennessee Overseas Co., has started upon oil exploration in Sierra Leone. C. W. Michel, Tennessee’s vice-president is already connected with oil through Dome Petroleum, a subsidiary of the Americo-Canadian Dome Mines Ltd., interlocked with Tennessee by shareholding and Michel’s chairmanship.

Africa is still paramountly an uncharted continent economically, and the withdrawal of the colonial rulers from political control is interpreted as a signal for the descent of the international monopolies upon the continent’s natural resources. This is the new scramble for Africa, under the guise of aid, and with the consent and even the welcome of young, inexperienced States. It can be even more deadly for Africa than the first carve-up, as it is supported by more concentrated interests, wielding vastly greater power and influence over governments and international organisations.