Kwame Nkrumah 1965

AFRICA is a paradox which illustrates and highlights neo-colonialism. Her earth is rich, yet the products that come from above and below her soil continue to enrich, not Africans predominantly, but groups and individuals who operate to Africa’s impoverishment. With a roughly estimated population of 280 million, about eight per cent of the world’s population, Africa accounts for only two per cent of the world’s total production. Yet even the present very inadequate surveys of Africa’s natural resources show the continent to have immense, untapped wealth. We know that iron reserves are put at twice the size of America’s, and two-thirds those of the Soviet Union’s, on the basis of an estimated two billion metric tons. Africa’s calculated coal reserves are considered to be enough to last for three hundred years. New petroleum fields are being discovered and brought into production all over the continent. Yet production of primary ores and minerals, considerable as it appears, has touched only the fringes.

Africa has more than 40 per cent of the world’s potential water power, a greater share than any other continent. Yet less than five per cent of this volume has been utilised. Even taking into account the vast desert stretches of the Sahara, there is still in Africa more arable and pasture land than exists in either the United States of America or the Soviet Union. There is even more than in Asia. Our forest areas are twice as great as those of the United States.

If Africa’s multiple resources were used in her own development, they could place her among the modernised continents of the world. But her resources have been, and are still being used for the greater development of overseas interests. Africa provided to Britain in 1957 the following proportions of basic materials used in her industries:

Yet in none of the new African countries is there a single integrated industry based upon any one of these resources.

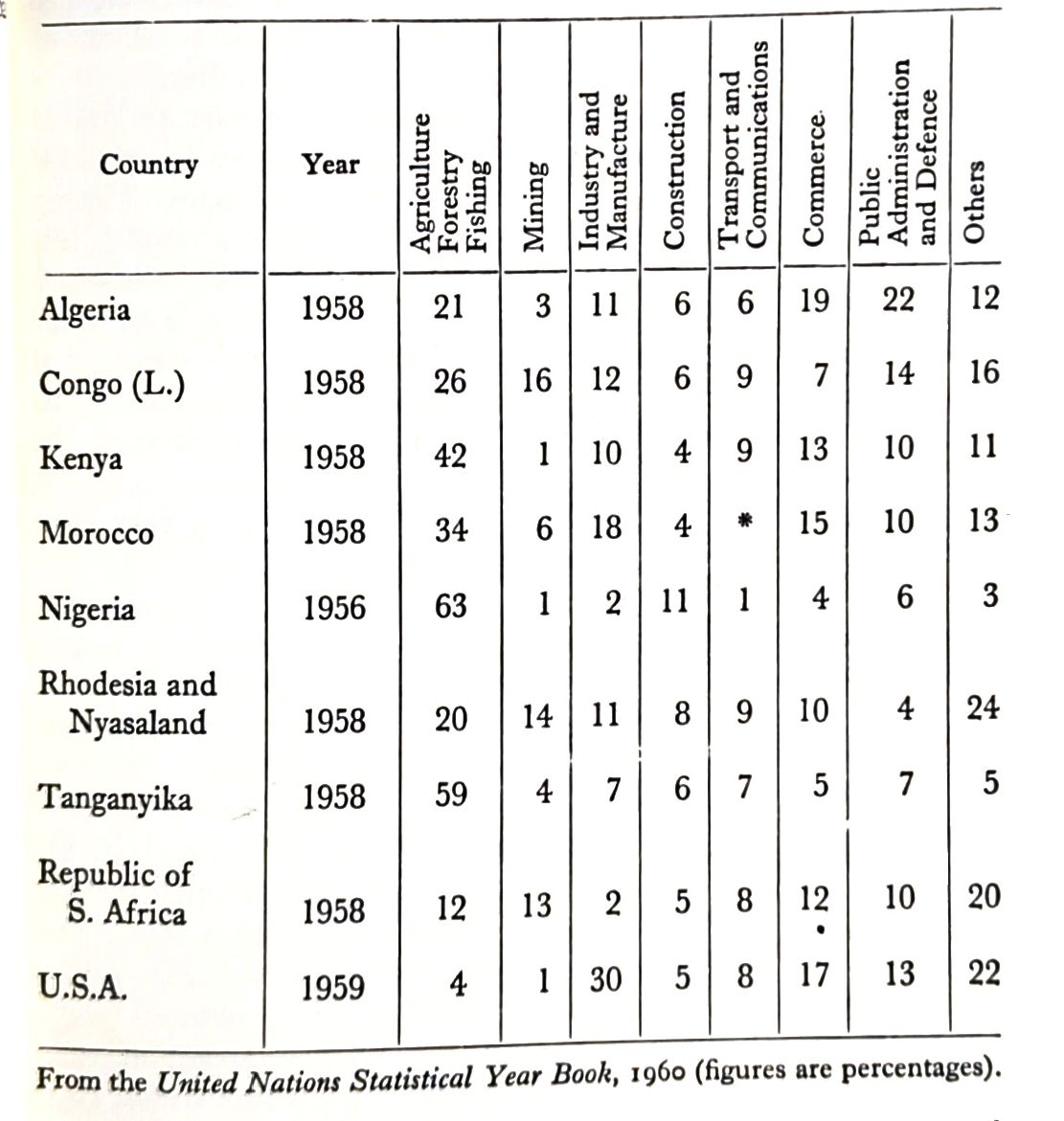

Although possessing fifty-three of the world’s most important basic industrial minerals and metals, the African continent tails far behind all others in industrial development. Gauged on the production of primary products output in the total economic activity, by comparison with the country of most advanced production, the United States of America, the facts can be seen at a glance.

It will be noted that in America agriculture, forestry and fishing provide a mere four per cent of the total national activity, and mining a trifling one per cent. On the other hand, industry, manufacture and commerce provide 47 per cent. In the African countries included in the table, which are, with the exception of Nigeria, those with the highest settler communities and therefore the most exploited, agriculture is predominant. Industry, manufacture and commerce lag far behind. Even in the case of South Africa, the most highly industrialised sector of the African continent, the contribution of agriculture (12 per cent) and mining (13 per cent) are equal to those of industry, manufacture and construction put together.

However, on the whole, mining has proved a most profitable venture for foreign capital investment in Africa. Its benefits for Africans have by no means been on an equal scale. Mining production in a number of African countries has a value of less than $2 per head of population. As Europe (France) Outremer puts it, ‘It is quite certain that a mining production of $1 or $2 per inhabitant cannot appreciably affect a country’s standard of living.’ Affirming correctly that ‘in the zones of exploitation, the mining industry introduces a higher standard of living’, the journal if forced to the conclusion that mining exploitations are, however, relatively privileged isolated islands in a very poor total economy.

The reason for this is seen in the absence of industry and manufacture, owing to the fact that mining production is destined principally for exportation, mainly in primary form. It goes to feed the industries and factories of Europe and America, to the impoverishment of the countries of origin.

It is also remarked by Europe (France) Outremer that about 50 per cent of Africa’s mining production remains in the country of origin as wages. Even the most cursory glance at the annual accounts of the mining companies refutes this claim. The excess of revenue over expenditure in many cases proves conclusively by its size that wages received by manual labour form by no means such an exaggerated proportion of value produced as 50 per cent. The considerable sums which go in highly paid salaries to European staffs in the skilled and administrative categories, part of which is returned to their own countries, must in many instances amount to the total received by African labour, to say nothing of the large amounts which swell the yearly incomes of wealthy directors who reside in the metropolitan cities of the west.

The assumption also ignores another important fact, namely that wages of manual workers, low as they are, are partly spent on goods manufactured abroad and imported, taking out of the primary producing countries a good part of the workers’ wages. In many cases, the imported goods are the products of the companies associated with the mining groups. Frequently, they are sold in the companies’ own stores on the mining compounds or by their appointed agents, the workers having to pay prices fixed by the companies.

The poverty of the people of Africa is demonstrated by the simple fact that their income per capita is among the lowest in the world.

In some countries, for example Gabon and Zabia, up to half the domestic product is paid to resident expatriates and to overseas firms who own the plantations and mines. In Guinea de Sao, Angola, Libya, Swaziland, South-West Africa and Zimbabwe (Rhodesia), foreign firm profits and settler or expatriate incomes exceed one-third of the domestic product. Algeria, Congo and Kenya were in this group before independence.

On achieving independence, almost every new state of Africa has developed plans for industrialisation and rounded economic growth in order to improve productive capacity and thereby raise the standard of living of its people. But while Africa remains divided progress is bound to be painfully slow. Economic development is dependent not only on the availability of natural resources and the size and population of a country, but on economic size, which takes into account both population and income per capita. In many African States the population and per capita products are extremely small, giving an economic unit no longer than a medium-sized firm in a western capitalist country, or a single State enterprise in a European socialist economy.

Africa is having to pay a huge price once more for the historical accident that this vast and compact continent brought fabulous profits to western capitalism, first out of the trade in its people and then out of imperialist exploitation. This enrichment of one side of the world out of the exploitation of the other has left the African economy without the means to industrialise. At the time when Europe passed into its industrial revolution, there was a considerably narrower gap in development between the continents. But with every step in the evolution of productive methods and the increased profits drawn from the more and more shrewd investment in manufacturing equipment and base metal production, the gap widened by leaps and bounds.

The Report of the U.N. Economic Commission for Africa published in December 1962 under the title of Industrial Growth in Africa states that the gap between ‘the continents separated by the Mediterranean’ has widened faster during the twentieth century than ever before. True, per capita output has increased in Africa, particularly in the last two decades, which have seen an increase of some 10 to 20 per cent. Already far ahead, the industrial countries have marked a per capita advance in the same period of 60 per cent, and their per capita industrial production may be estimated as high as twenty-five times that in Africa as a whole. The difference for the greater part of Africa, however, is even more marked, since industry on this continent tends to be concentrated in small areas in the north and south. A real transformation of the African economy would mean not only doubling agricultural output but increasing industrial output some twenty-five times. The Report makes plain that industry rather than agriculture is the means by which rapid improvement in Africa’s living standards is possible.

There are, however, imperialist specialists and apologists who urge the less developed countries to concentrate on agriculture and leave industrialisation for some later time when their populations shall be well fed. The world’s economic development, however, shows that it is only with advanced industrialisation that it has been possible to raise the nutritional level of the people by raising their levels of income. Agriculture is important for many reasons, and the governments of African states concerned with bringing higher standards to their people are devoting greater investment to agriculture. But even to make agriculture yield more the aid of industrial output is needed; and the under-developed world cannot for ever be placed at the mercy of the more industrialised. This dependence must slow the rate of increase in our agriculture and make it subservient to the demands of the industrial producers. That is why we cannot accept such sweeping assessments as that made by Professor Leopold G. Scheidl of the Vienna School of Economics at a recent meeting in London of the International Geographical Congress. Commented Professor Scheidl: ‘People in developing countries seem to think that all that is necessary for them to become as wealthy as the west is to build factories. Most experts agree that it is wiser and more promising to develop agriculture into self-sufficiency and on to the level of a marketing economy’ (The Times, 24 July 1964). This train of thought links up directly with that of the chairman of Booker Brothers, Sir Jock Campbell whose combine of companies is busy monopolising sugar and by-product industries in British Guiana, shipping and trading in the Caribbean and East Africa, and is now penetrating into the west of the African continent. Sir Jock Campbell asserted at the Annual address of the African Bureau in London on 29 November 1962 that ‘agriculture was the basis of African development and that plantations were an effective method of increasing economic potential’. He considered that ‘so long as industrialised agriculture employed men free to come and go, it was preferable in terms both of efficiency and liberty to the communised collective farming whose results had fallen so short of expectation in Russia and China’ (The Times, 30 November 1962). He does not seem to have convinced the sugar workers of British Guiana, and it is a moot point whether he has been able to impress the benefits of his ‘free to come and go’ plantation philosophy on the workers for his companies in Nyasaland, Rhodesia and South Africa. Even the scientific supporters of the imperialist pattern are aware of the flaws in their injunctions, but they cunningly attribute the emphasis placed by the developing states upon industrialisation to political ambitions rather than to economic and social necessity. A European representative of the University of Malaya, Mr D. W. Fryer, speaking at the meeting of the International Geographical Conference to which reference is made above, said that ‘an increase in the efficiency of traditional export industries in the under-developed countries was an obvious move, but it was politically unattractive. It suggested continued acceptance of the old colonial economy. ... Industrialism was an integral part of the nationalist movement. Its mainspring was not economic but political, and political expediency was often more important than economic efficiency in the location of new industry’.

The more efficient management of primary production and improvement on a marketing level is imperialism’s gain and our loss. The point has been made quite clearly by no less a person than the chairman of Bolsa (the Bank of London and South America), Sir George Bolton. The latter was reported in The Financial Times of 6 March 1964 as being confident of a rise in commodity prices, which would have considerable effect on the foreign exchanges. For whose benefit? Sir Goerge provides the answer. ‘It should help the reserve currencies, sterling and the dollar,’ he said. Why? Because being tied to these currencies, ‘the primary producers will be accumulating their surpluses in sterling and dollar balances’. This appears to be nothing short of a direct confession of the major interest of the banking and financial world in the exploitation of the developing countries. It is interesting, therefore, to note that Bolsa’s transfer agents in London are Patino Mines & Enterprises Consolidated, the American-controlled combine operating mines in Latin America and Canada, and intimately associated with the groups engaged in exploiting Africa’s natural resources.

We are certainly not against marketing and trading. On the contrary, we are for a widening of our potentialities in these spheres, and we are convinced that we shall be able to adjust the balance in our favour only by developing an agriculture attuned to our needs and supporting it with a rapidly increasing industrialisation that will break the neo-colonialist pattern which at present operates.

A continent like Africa, however much it increases its agricultural output, will not benefit unless it is sufficiently politically and economically united to force the developed world to pay it a fair price for its cash crops.

To give one illustration. Both Ghana and Nigeria have in the post-war independence period enormously developed their production of cocoa, as the table [below]shows.

This result has not been obtained by chance, it is the consequence of heavy internal expenditure on control of disease and pests, the subsidising of insecticides and the spraying machines provided to farmers and the importing of new varieties of cocoa seedlings which are resistant to the endemic ills which previously cocoa trees had developed. By means such as these Africa as a whole greatly increased her cocoa production, while that of Latin America remained stationary.

What advantage has Nigeria or Ghana gained through this stupendous increase in agricultural productivity? In 1954/5 when Ghana’s production was 210,000 tons, her 1954 earnings from the cocoa crop were £85 1/2 million. This year (1964/5) with an estimated crop of 590,000 tons, the estimated external earnings will be around £77 million. Nigeria has suffered a similar experience. In 1954/5 she produced 89,000 tons of beans and received for her crop £39 1/4 million. In 1965 it is estimated that Nigeria will produce 310,000 tons and is likely to receive for it around £40 million. In other words, Ghana and Nigeria have trebled their production of this particular agricultural product but their gross earnings from it have fallen from £125 million to £117 million.

A detailed study of production and price shows that it is the developed consuming country which obtains the advantage of the increased production in the less developed one. So long as African agricultural producers are disunited they will be unable to control the market price of their primary products.

As experience with the Cocoa Producers Alliance has shown, any organisation which is based on a mere commercial agreement between primary producers is insufficient to secure a fair world price. This can only be obtained when the united power of the producer countries is harnessed by common political and economic policies and has behind it the united financial resources of the States concerned.

So long as Africa remains divided it will therefore be the wealthy consumer countries who will dictate the price of African cash crops. Nevertheless, even in Africa could dictate the price of its cash crops this would not by itself provide the balanced economy which is necessary for development. The answer must be industrialisation.

The African continent, however, cannot hope to industrialise effectively in the haphazard, laisser-faire manner of Europe. In the first place, there is the time factor. In the second, the socialised modes of production and tremendous human and capital investments involved call for cohesive and integrated planning. Africa will need to bring to its aid all its latent ingenuity and talent in order to meet the challenge that independence and the demands of its peoples for better living have raised. The challenge cannot be met on any piece-meal scale, but only by the total mobilisation of the continent’s resources within the framework of comprehensive socialist planning and deployment.

We have noted that in the countries of the highest settler populations, and therefore the most exploited so far in Africa (Algeria, Congo, Kenya, Morocco, Rhodesia, Malawi, South Africa, Tanganyika), agriculture is predominant. In the case of South Africa, the most highly developed area of the African continent, the contribution of agriculture and mining is together, equal to that of industry, manufacture and construction. South Africa’s economy is heavily bolstered by the export of its mining output. Gold contributes up to 70 per cent of the total exports, which makes the economy, for all its apparent boom, and the heavily increasing foreign investment, basically almost as insecure as that of the less developed countries of the continent. For all its pushing secondary industries, its chemicals manufacture, military production, steel processing and the rest, South Africa has so far failed to lay down the basis of solid industrialisation. G. E. Menell, chairman of Anglo-Transvaal Consolidated Investment Company, which controls gold, diamonds and uranium, made a most telling statement in his annual address on 6 December 1963 to the Johannesburg shareholders’ meeting. ‘The nation’s economy is based, to a significant degree, on wasting assets – the gold mines of the Transvaal and Orange Free State. We have become more and more aware of this in recent years as more mines near the end of their lives without any sign of new large goldfields, in spite of the many millions being spent on exploration.’

Investment in South Africa’s economy comes mainly from Western capital with which local finance, not hardly enough to stand on its own feet, is strongly bound. Quick profits are the incentive, so that while Anglo-Transvaal’s chairman sees the dangers to the economy, he was nonetheless happy to be able to announce that record profits were again achieved in 1963.

The whole of the economy is geared to the interests of the foreign capital that dominates it. South Africa’s banking institutions, like those of most other African States, are offshoots of the Western banking and financial houses. South Africa is dominated by western monopoly even more than by any other sector of the continent, because the investments are many times greater and the dependence upon gold and other mining as the centre of the economy gears it inextricably to that monopoly. Its vulnerability is intensified by the fact that it is a supplier of crude and semi-finished products to the factories of the west on a larger scale than the rest of Africa, and an earner of greater profits for their financial backers.

Nigeria tells in a few basic figures a tale of a different kind of economic maladjustment. In 1960 agriculture, forestry and fishing accounted for 63 per cent of the economic activity; mining one per cent. The imbalance is emphasised by the extremely low ratio of two per cent for industry and manufacture, eliminating at once any comparison with the one per cent contribution of mining and four per cent of agriculture to America’s total economic product. In the case of the United States, this low proportion supports a vast superstructure of industry and manufacture. In Nigeria it connotes simply a total disregard under colonialism of Nigeria’s potentialities. The reason for this lies not in the fact that Nigeria is devoid of natural industrial resources, as recent findings of oil and iron confirm. It was that Nigeria’s agriculture provided greater profitability for European investment than the risks that were involved in the larger capital provisions called for by mining exploration and exploitation.

In 1962 petroleum and petroleum products contributed 9·9 per cent to Nigeria’s exports, but it is Shell-BP that hopes to reap most of the benefits. The bulk of these exports was in crude oil, exceeding three million tons. The oil company is aiming at an export target of five million tons of crude oil by 1965. Processing plants are in Europe, not in Nigeria.

The oil refinery going up in Port Harcourt is owned by Shell-BP; the natural gas piping is owned by Shell-Barclays D.C. & O. The oil refinery is meant to handle only ten per cent of Nigeria’s crude oil output, and its products will serve only Nigeria’s domestic market. Such an arrangement makes it possible not to disturb operations outside Nigeria while making super profits on Nigerian operations.

Generally speaking, in spite of the exploration costs, which are written off for tax purposes anyway and many times covered by eventual profits, mining has proved a very profitable venture for foreign capital investment in Africa. Its benefits for the Africans on the other hand, despite all the frothy talk to the contrary, have been negligible.

This is explained by the absence of industry and manufacture based upon the use of domestic natural resources, and of the trade that is their continent. For mining production is destined principally for exportation in its primary form. Certain exceptions to this generalisation are to be found in South Africa, Zambia and the Congo. Some small conversion has been taking place also in countries like Morocco, Algeria, Mozambique. South Africa’s copper is exported in the form of metal and a small part of its iron is sent overseas as ingots; its gold is refined. But for these exceptions, most exported minerals are shipped from Africa in their primary state. They go to feed the industries and plants of Europe, America and Japan. The ore that is to be produced in Swaziland by the Swaziland Iron Ore Development Company (owned jointly by Anglo-American Corporation and the powerful British steel group, Guest Keen & Nettlefolds) will go at the rate of 1,200,000 tons annually for ten years from 1964 to a Japanese steel combine.

When the countries of their origin are obliged to buy back their minerals and other raw products in the form of finished goods, they do so at grossly inflated prices. A General Electric advertisement carried in the March/April 1962 issue of Modern Government informs us that ‘from the heart of Africa to the hearths of the world’s steel mills comes ore for stronger steel, better steel – steel for buildings, machinery, and more steel rails’. With this steel from Africa, General Electric supplies transportation for bringing out another valuable mineral for its own use and that of other great imperialist exploiters. In lush verbiage the same advertisement describes how ‘deep in the tropical jungle of Central Africa lies one of the world’s richest deposits of manganese ore’. But is it for Africa’s needs? Not at all. This site, which is ‘being developed by the French Concern, Compagnie Minière de l'Ogooue, is located on the upper reach of the Ogooue River in the Gabon Republic. After the ore is mined it will first be carried 50 miles by cableway. Then it will be transferred to ore cars and hauled 300 miles by diesel-electric locomotives to the port of Point Noire for shipment to the world’s steel mills’. For ‘the world’ read the United States first and France second.

That exploitation of this nature can take place is due to the balkanisation of the African continent. Balkanisation is the major instrument of neo-colonialism and will be found wherever neo-colonialism is practised.