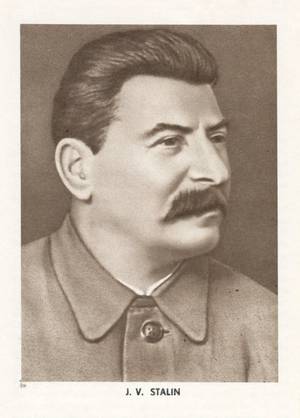

J. V. Stalin

The Tenth Anniversary of Pravda

(Reminiscences)

May 5, 1922

Source : Works, Vol.

5, 1921 - 1923

Publisher : Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow,

1954

Transcription/Markup : Salil Sen for MIA, 2008

Public Domain : Marxists Internet Archive (2008).

You may freely copy, distribute, display and perform this work; as well as make

derivative and commercial works. Please credit "Marxists Internet Archive" as

your source.

1. The Lena Events

The Lena events were the result of the Stolypin regime of "pacification." The younger members of the Party, of course, have not experienced and do not remember the charms of this regime. As for the old ones, they, no doubt, remember the punitive expeditions of accursed memory, the savage raids on working-class organisations, the mass flogging of peasants, and, as a screen to all this, the Black-Hundred-Cadet Duma. Public opinion in shackles, general lassitude and apathy, want and despair among the workers, the peasantry downtrodden and terrified, with gangs of the police, landowners and capitalists rampant everywhere—such were the typical features of Stolypin's "pacification."

The Lena events were the result of the Stolypin regime of "pacification." The younger members of the Party, of course, have not experienced and do not remember the charms of this regime. As for the old ones, they, no doubt, remember the punitive expeditions of accursed memory, the savage raids on working-class organisations, the mass flogging of peasants, and, as a screen to all this, the Black-Hundred-Cadet Duma. Public opinion in shackles, general lassitude and apathy, want and despair among the workers, the peasantry downtrodden and terrified, with gangs of the police, landowners and capitalists rampant everywhere—such were the typical features of Stolypin's "pacification."

To the superficial observer it might have seemed that the epoch of revolution had passed away forever, and that a period of the "constitutional" development of Russia on the lines of Prussia had set in. The Menshevik Liquidators openly shouted that this was so and preached the necessity of organising a Stolypin legal workers' party. And certain old "Bolsheviks," who in their hearts sympathised with this preaching, made haste to desert the ranks of our Party. The triumph of the knout and the powers of darkness was complete. At that time the political life of Russia was described as an "abomination of desolation."

The Lena events burst into this "abomination of desolation" like a hurricane and revealed a new picture to everybody. It turned out that the Stolypin regime was not so stable after all, that the Duma was rousing the contempt of the masses, and that the working class had accumulated sufficient energy to rush into battle for a new revolution. The shooting down of workers in the remote depths of Siberia (Bodaibo on the Lena) sufficed to call forth strikes all over Russia, and the St. Petersburg workers poured into the streets and at one stroke swept from the path the boastful Minister Makarov and his insolent slogan "So it was, so it will be." These were the first harbingers of the mighty movement that was then beginning. Zvezda 1 was right when it exclaimed at that time: "We live! Our scarlet blood seethes with the fire of unspent strength. . . ." The upsurge of a new revolutionary movement was evident.

It was in the waves of this movement that the mass working-class newspaper Pravda was born.

2. The Foundation of Pravda

It was in the middle of April 1912, one evening at Comrade Poletayev's house, where two members of the Duma (Pokrovsky and Poletayev), two writers (Olminsky and Baturin) and I, a member of the Central Committee (I, being in hiding, had found "sanctuary" in the house of Poletayev, who enjoyed "parliamentary immunity") reached agreement concerning Pravda's platform and compiled the first issue of the newspaper. I do not remember whether Demyan Byedny and Danilov, two very close contributors to Pravda, were present at this conference.

The technical and financial prerequisites for the newspaper had already been provided thanks to the agitation conducted by Zvezda, the sympathy of the broad masses of the workers, and the mass voluntary collection of funds for Pravda in the mills and factories. Truly, Pravda came into being as a result of the efforts of the working class of Russia, and above all of St. Petersburg. Had it not been for these efforts, the newspaper could not have existed.

Pravda's complexion was clear: its mission was to popularise Zvezda's programme among the masses. In its very first issue Pravda wrote: "Anyone who reads Zvezda and knows its contributors, who are also contributors to Pravda, will not find it difficult to understand the line Pravda will pursue." 2 The only difference between Zvezda and Pravda was that the latter, unlike the former, did not address itself to the advanced workers, but to the broad masses of the working class. It was Pravda's function to help the advanced workers to rally around the Party's banner the broad strata of the Russian working class who had awakened for a fresh struggle but were still politically backward. That is precisely why one of the aims Pravda set itself at that time was to train writers from among the workers and to draw them into the work of directing the paper.

In its very first issue Pravda wrote: "We would like the workers not to confine themselves to sympathy alone, but to take an active part in the conduct of our newspaper. Let not the workers say that they are ‘not used to' writing. Working-class writers do not drop ready-made from the skies, they can be trained only gradually, in the course of literary activity. All that is needed is to start on the job boldly: you may stumble once or twice, but in the end you will learn to write. . . ." 3

3. The Organisational Significance of Pravda

Pravda made its appearance in that period of our Party's development when the underground organisation was entirely in the hands of the Bolsheviks (the Men-sheviks had fled from it), but the legal forms of organisation—the group in the Duma, the press, sick-benefit societies, insurance societies, trade-union organisations —had not yet been completely won from the Mensheviks. It was a period in which the Bolsheviks were waging a determined struggle to expel the Liquidators (Mensheviks) from the legal working-class organisations. The slogan "Dismiss the Mensheviks from their posts" was then a most popular slogan of the working-class movement. The columns of Pravda bristled with reports of the expulsion from the insurance societies, sick-benefit societies and trade-union organisations of the Liquidators who at one time had entrenched themselves in them. All six deputies' seats in the workers' curia had been won from the Mensheviks. The Menshevik press was also in the same, or almost the same, hopeless position. It was truly a heroic struggle that the Bolshevik-minded workers waged for the Party, for the agents of tsarism were wide awake, hunting and rooting out the Bolsheviks, and the Party, driven deep underground, could not develop further unless it had a legal cover. More than that: under the political conditions prevailing at that time, the Party could not put out feelers towards the broad masses and rally them around its banner unless it won the legal organisations; it would have been cut off from the masses and would have been transformed into an isolated group, stewing in its own juice.

Pravda was the centre of this struggle for the Party principle, for the creation of a mass workers' party. It was not merely a newspaper that summed up the successes of the Bolsheviks in winning the legal workers' organisations; it was also the organising centre which united these organisations around the underground centres of the Party and directed the working-class movement towards a single definite goal. Already in his book What Is To Be Done? (1902), Comrade Lenin had written that a well-organised all-Russian militant newspaper must be not only a collective agitator, but also a collective organiser. That is exactly the kind of newspaper which Pravda became in the period of the struggle against the Liquidators for the preservation of the underground organisation and for winning the legal organisations of the workers. If it is true that, had we not defeated the Liquidators we would not have had the Party which, strong in its unity and invincible because of its devotion to the proletariat, organised October 1917, then it is equally true that the persevering and devoted struggle of the old Pravda to a considerable degree prepared and hastened this victory over the Liquidators. In this sense the old Pravda was undoubtedly the herald of the future glorious victories of the Russian proletariat.

Pravda, No. 98, May 5, 1922

Notes

1. Zvezda (The Star) — a legal Bolshevik newspaper published in St. Petersburg from December 16, 1910 to April 22, 1912, first weekly and later two or three times a week. It was under the ideological guidance of V. I. Lenin, who regularly sent articles for it from abroad. Regular contributors to the paper were V. M. Molotov; M. S. Olminsky, N. G. Poletayev, N. N. Baturin, K. S. Yeremeyev and others. Contributions were also received from Maxim Gorky. In the spring of 1912, when J. V. Stalin was in St. Petersburg, the paper came out under his direction, and he wrote a number of articles for it (see Works, Vol. 2, pp. 231-54). The circulation of individual issues of the paper reached 50,000 to 60,000. Zvezda paved the way for the publication of the Bolshevik daily Pravda. On April 22, 1912, the tsarist government suppressed Zvezda. It was succeeded by Nevskaya Zvezda, which continued publication until October 1912. p. 132

2. Quoted from J. V. Stalin's article "Our Aims," published in Pravda, No. 1, April 22, 1912 (see Works, Vol. 2, p. 255). p. 133

3. See J. V. Stalin, Works, Vol. 2, p. 256. p. 134