Communist Party of Australia. 1943

Source: “The Story of J T Lang,” by R. Dixon.

Printed: by Mastercraft Printing & Publishing Co., 1943;

Transcribed: by Andy Blunden.

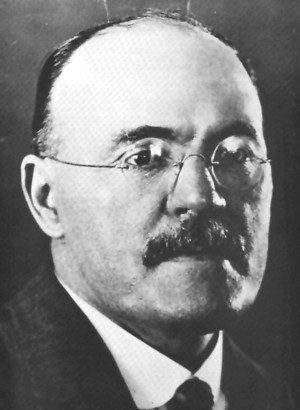

On Friday, March 5th, 1943, Mr. J. T. Lang, former Labor Premier and leader, was expelled from the Labor Party by the N.S.W. Executive of the Official Labor Party. For 16 years Lang had dominated the Labor Party in N.S.W. and was one of the central figures in Australian politics. From the year 1923, when he first became leader of the Labor Party in the N.S.W. Parliament, until 1939, when he was at last removed from that position, Mr. Lang was responsible for the expulsion of more members from the Labor Party than any other man in the history of the Labor Party. His path in the labor movement is strewn with the political skulls of his opponents. But the wheel has taken a full turn and now the chief executioner himself is the victim. And Lang does not like it.

“I have been expelled from the Labor Party,” he wailed. (“Century,” 12/3/43.)

“I have never been false to the great humanitarian principles on which Labor’s policy and platform is based.”

“This Executive will learn that it can’t save itself or the Governments by shooting its critics,” he wrote, as though suddenly realising that all’ the expulsions he himself land engineered had been in vain.

But Lang has learnt nothing. His threat to destroy the Curtin and McKell Labor Governments, evidenced in the above paragraph, is what we have come to expect from him. He is the typical disruptor. He destroyed not only Labor men, but Labor Governments. He kept the Labor Party in opposition for ten vital years in the history of Australia. He split the Labor Party and threw the workers into confusion. Whatever Lang put his hand to he turned to his own advantage and against the worker.

When the N.S.W. Executive expelled Lang, they drew attention to the fact that he holds shares in the “Century” newspaper to the value Of £19,407. That’s a lot of money for a man who has always been true to the “great humanitarian principles” of labor to amass. And besides his “Century” investment, Lang has money sewn up in land and property, in radio stations and the profitable business of burying the dead.

What can this wealthy capitalist, J. T. Lang, have in common with the working man?

Lang parades himself to-day as a great anti-conscriptionist. In the “Century” of March 12th, he wrote: “When a Labor Prime Minister says to me and to the people, I must introduce conscription because my military advisers tell me it is necessary, I can see no difference between that man and Hughes who, 25 years ago, tried to do the same thing and gave exactly the same reasons.”

What did Mr. Lang do 25 years ago?

Lang was first elected to the N.S.W. Parliament as the representative for Granville, in 1913, the year before the outbreak of the world Imperialist War. He was an estate agent. Because of his very “’conservative” views he was not readily acceptable in Labor Party circles at the time. As a matter of fact, in 1921, the Labor Part y v executive seriously considered refusing Lang endorsement as a L.P. candidate because he was “too moderate.”

When the conscription issue arose, Mr. Lang was found ‘,sitting on the fence,” reluctant to declare himself. An estate agent, and a Labor Party “conservative,” he was, nevertheless, the representative of Granville, a working class electorate that was firmly anti-conscriptionist. If he joined forces with Holman he would have to find another electorate, because the Labor Party was refusing endorsement to conscriptionists. The Liberals (U.A.P. to-day) were prepared to find safe seats for Hughes and Holman, but they were not much concerned about the political future of J. T. Lang.

What was he to do?

His closest supporters in the Granville Labor League pleaded with Lang to oppose conscription if he wished to retain the Granville seat. He finally agreed to do this. Lang had no enthusiasm for the decision and gave very little support to the campaign. In the whole of the 1916 anti-conscription campaign he is reported to have addressed only two or three meetings.

Not a very brilliant performance for one who, to-day, is trying to cash in on the great struggle waged by the Labor Movement in 1916 and who is vilifying those Labor leaders who organised and led that campaign while he, Lang, did nothing but sabotage it.

Lang was nearly a conscriptionist in 1916, when the Labor Movement *M duty bound to oppose conscription. The war of 1914-18 was an Imperialist War which it was necessary to oppose. The present War, however, is not an imperialist War, but a People’s War against Fascism. It is a Just War which it is the duty of the working class to support. In these circumstances the position taken up by the Labor Movement in 19A must be reversed. Mr. Curtin was absolutely right and did not depart from working class principles, when he urged an alteration of the Defence Law to allow of the Militia Forces being used in the South West Pacific battle area. It was J. T. Lang, and the war-shy heroes supporting him, who betrayed the principles of Labor.

In 1916, when it was correct working class policy to oppose conscription, Lang had to he forced into line with the Labor Movement. In 1942-3, when working class policy demands support for Curtin’s Militia proposals, Lang is to be found in opposition, ranting against the Curtin Government and betraying working class principles.

The “conservative” of 19A is still the Labor reactionary in 1943.

“When a Labor leader says to me I must tax, and tax heavily, ever), wage earner earning more than £2 per week because my financial advisers tell me it is essential to preserve the financial stability of the country, I can wee no difference between that man and Lyons and Stevens who, ten years ago, said they had to tax and reduce wages in the interests of sane finance.”

Mr. Lang, whose facility for ignoring the past and twisting facts is unsurpassed, made that statement in the “Century,” March 12th, 1943.

Instead of ten years, let us go back thirteen years. On May 29th, 1930, Mr. (“Tubby”) Stevens, treasurer in the Bavin Government, proposed a bill to the N.S.W. Parliament, the Unemployment Relief Bill, providing for a tax Of 3d. in the £1 on the wages of workers with incomes as low as £2 per week.

Lang denounced the scheme as one of the most “diabolical” ever conceived by a Government to raise money and urged its rejection.

He said: “A more disgraceful piece of legislation has never been introduced in any Parliament. It could only be introduced by a Party that is bowelless, by a Party that has none of the milk of human kindness in its composition.’’

Six months later, in November, 193o, the State Elections took place in N.S.W. In his policy speech Lang promised to “review the Unemployment Relief Act and also the incidence of the Taxation imposed by it.”

The Labor Party was elected and Lang became Premier and Treasurer.

In December, 1930, the great J. T. Lang, so full of the “milk of human kindness” so true to “the great humanitarian principles on which Labor’s policy and platform is based,” introduced a new Prevention and Relief of Unemployment. Bill. Under Mr. Lang’s new bill, the “diabolical” tax imposed by Stevens, was increased from 3d. in the £1 to 1/- in the £1 on incomes of £2 per week and over. In no other State in Australia were the workers taxed so heavily as by the Lang Government in N.S.W. And in no other State of Australia, except Victoria, were the sustenance rates to the unemployed so low as in N.S.W. under the Lang regime.

Mr. Lang has made great capital out of the fact that his Government introduced Pensions for Widows and Child Endowment. He has sought all the credit for himself. It is interesting, therefore, to know that on the eve of the 1925 elections, when Mr. Lang submitted his policy speech to the Labor Party Caucus, it contained nothing about Widows’ Pensions. The Caucus voted for the inclusion of Widows’ Pensions, against the wishes of Lang. (In those days he was not yet strong enough to dispense with Caucus meetings as was the case later.)

Child Endowment, on the other hand, does not rebound to the credit of Lang, but to his detriment. It served to cover up one of the most vicious wage cuts ever put over in this country.

In 1926, the N.S.W. Basic Wage was £4/4/- per week, the lowest in the Commonwealth. Lang appointed Mr. justice Piddington to fix a living wage for a family unit of four, for’ a man, wife and two children.

Piddington discovered that the existing N.S.W. Basic Wage,’ & 4/4/- per week, was a living wage for a family unit of two, for man and wife only, and that £4/16/-, or a 12/- rise in the Basic Wage, would be necessary to provide a living wage for a family unit of four. Piddington proposed, however, that instead of declaring £,4/16/- the Basic Wage, that a Child Endowment scheme be introduced, providing 6/- per week per child and that the Basic Wage remain at £4/4-/-.

The Trade Unions and Labor organisations denounced the Piddington scheme and urged Lang to increase the Basic Wage. Child Endowment, they insisted, should not be substituted for a justifiable increase in the Basic Wage but should be considered over and above the Basic Wage.

But Lang was opposed to any substantial increase in the Basic Wage, no matter how necessary it was. He saw in Child Endowment a means of saving Industry and Employers millions of pounds. In June, 1927, six months after Piddington issued his findings, Lang’s Child Endowment scheme came into operation. It provided for 5/- per week and not 6/- as proposed by Piddington.

But what was the cost of Child Endowment to the workers of N.S.W.? First of all there was that period between December, 1926, when Piddington issued his findings on the Basic Wage, and June, 1927, when endowment payments commenced. During the whole of that period the totally inadequate Basic Wage of £4/4/- remained unaltered. Piddington, in his findings, estimated that every 1/- increase in the Basic Wage meant £1,000,000 per year more in wages to the workers. The six months’ delay, between December, 1926, and June, 1927, when Lang’s Endowment scheme began to operate and during which the Basic Wage remained at £4/4/- per week, or 12/- below the wage the workers were entitled to, cost the workers £6,000,000 in wages.

But that amount is small compared with the wage robbery achieved by the Child Endowment scheme generally. Taking Piddington’s figures that a 1/- rise in the Basic Wage would put £1,000,000 a year more into the pockets of the workers of N.S.W., it follows that had Lang declared for a 12/- increase in the Basic Wage, which would have been in accordance. with Piddington’s findings, and with the demands of the Trade Union Movement, the workers of this State would have benefited to the extent of £12,000,000 per year. The cost of Child Endowment, on the other hand, was less than £2,000,000 per year, a discrepancy of £10,000,000. Instead Of £12,000,000, the workers got £2,000,000.

Mr. Lang’s Child Endowment Bill was a god-send to the Employers. By one fell swoop he deprived the workers of N.S.W. of a mere £10,000,000 per year in wages.

The economic crisis that broke out in 1929, and threw millions of workers throughout the capitalist world out of the industries to suffer misery and want, was, according to J. T. Lang, the result of a conspiracy of “financial manipulators,” and bankers-foreign bankers especially. He told hair-raising stories about Sir Otto Niemeyer, the Guggenheimers and other foreign bankers.

For Lang, whose knowledge of economics never got beyond the estate agency stage, the solution of the crisis was a simple matter. He would deal with the financiers and break up the “conspiracy.” He would put the unemployed to work and restore business and profits to their former prosperity.

The capitalists believed that the way to end the crisis was to slash the wages of the workers. ‘Lang denounced this course and attacked the bondholders.

This was the background to the N.S.W. State elections held in October, 1930, when Lang was returned to Parliament with the greatest Labor majority in the history of the State.

And what happened then?

The crisis refused to disappear. Instead, it got worse. Factories were closing down or reducing staffs, unemployment was increasing at a very rapid rate, the farmers were more impoverished than ever and bankruptcies were growing.

Lang went to work, but not on the Financial Oligarchy that he had so roundly denounced prior to and during the elections. He taxed the wages of the workers 1/- in the £. He put single unemployed on a dole of 5/9 per week, and man and wife on 8/9. He arranged for a “means test,” which he called the “Permissible Income Regulations,” that deprived thousands of even this miserable dole. In the Railways, Tramways and other Government undertakings he put the workers on short time, and he wiped the buses off the streets so as to enable the Railways and Tramways to meet payments of interest to the bondholders.

The bankers and bondholders were pleased. Lang was learning.

In May-June of 1931, there took place a Premiers’ Conference, where a scheme, that has come to be known as the “Premiers’ Plan,” was devised, intended to place the main burdens of the crisis on the backs of the workers. The Premiers’ Conference, which incidentally was dominated by Labor Premiers, decided to reduce Government expenditure, including wages, salaries and pensions, by 20%.

When the full meaning of this infamous decision broke upon the people, the resentment was so great that Lang tried to get out from under. He denounced the Premiers’ Conference. His well-paid propagandists sought to create the impression that Lang had refused to be a party to the decision, and had not signed the Premiers’ Plan.

But there is no doubt about Lang’s part in the proceedings. The decisions of the Premiers’ Conference had to be unanimous to be effective. The official report of the proceedings of the Premiers’ Conference records, on p. 75, the following minute, relating to the fateful decision that led to the wage slashing and undermining of living standards.

“Mr. Lang: As Acting-Chairman I shall put Mr. Hogan’s motion in the form in which it has been amended as we have proceeded. It is: ‘That for the guidance of the Legal Sub-Committee, the Conference is of the opinion that there should be a reduction of 20% in all adjustable Government expenditure as compared with the year ending June 30th, 1930, including all emoluments, wages, salaries and pensions paid by the Governments, whether fixed by Statute or otherwise, such reductions to be equitably effected.’

“The motion was agreed to.”

There can be no disputing the official record of the Premiers’ Conference. Mr. Lang was a party to that wage slashing decision and when he returned to N.S.W. he passed the necessary legislation to give effect to the wage cuts as proposed by the Premiers’ Conference.

Lang had taxed the workers, put the unemployed on a starvation dole and reduced wages – everything the bankers, and particularly Sir Otto Niemeyer, had asked for. He never ceased railing against the bankers, of course. As a matter of fact, the harder he hit the workers and farmers the more he ranted about the “conspiracy of financiers.”

Then he produced his ‘Tang Plan,” which was to put an end to the crisis, restore prosperity, and solve everything.

The “Lang Plan” was a typical piece of Lang deception. All it proposed was a reduction of interest rates on internal and overseas debts. Now the dumbest person in the land realised that there must be a reduction of interest rates but Lang’s propagandists dressed this idea up as a discovery of genius. And in order to make it appear more “revolutionary” they began to talk “repudiation.” Early in 1931, Lang, because N.S.W. was virtually bankrupt, did refuse to meet interest payments to British bondholders, until they agreed to a reduction of interest rates. This added fuel to the flames. People began to believe that Lang really intended to repudiate debts.

But what was Lang’s attitude to repudiation?

In his policy speech during the 1930, elections, Lang had this to say:

“Of this the people can be assured. The Australian Labor Movement would not permit for one moment any of its leaders to be associated with a policy of repudiation.”

Later, in August, 1931, when the great National Debt Conversion Loan was under way and bondholders were being urged to reconvert their bonds at a lower interest rate, Lang in a National broadcast, said:

“Every bondholder here has in his possession a contract with some individual Australian Government which carries on its face an obligation to pay a rate of interest ranging mostly from t to 6 per cent. Supporting that bond in the tradition that no Parliament under the British system would abrogate its written contracts.” (Our emphasis.)

That doesn’t sound like repudiation!

Lang concluded his broadcast with these words:

“In conclusion, let me say that to the patriotic bondholder there is no need to make any appeal, but to the man who views the Conversion Plan solely from the point of view of financial advantage, I would say, convert your bonds and make money.” (Our emphasis.)

So J. T. Lang was the friend of the bondholder after all. He merely wanted them to “convert their bonds and make money.” When it came to “repudiation” he was content to repudiate the promises he made to the workers to maintain living standards and put the unemployed to work.

When people began to wake up to the swindle of the ‘Tang Plan,” Lang had. to cook up a new idea, which he promptly did and called it “Socialisation of Credit.”

“Socialisation of Credit” was supposed to be the most profound economic idea of the century. No one, not even jack Lang himself, knew what it really meant. It had this advantage, however, that the bankers, believing that “Socialisation of Credit” was in some way directed at them, bitterly opposed it and Lang’s supporters, therefore, believed he had something.

This much was clear from Lang’s magic formula, that the Nationalisation of Banking was intended, which was nothing new, as the Labor Party for many years talked of Nationalising the banks, but had done nothing about it. What the taking over and running of the banks by the Capitalist State has to do with “Socialisation of Credit” neither Lang, nor anyone else could explain. We do have in this country, a number of banks, the Commonwealth Bank, and various State Savings Banks that are Government controlled. The N.S.W. State Savings Bank was a case in point. Mr. Lang, when he was in office, had every opportunity, through the N.S.W. State Savings Bank, of demonstrating the amazing qualities of “Socialised Credit” and yet all he succeeded in doing, he and his opponents, was to burst the bank.

The use of the word “Socialisation,” or rather its misuse, was, no doubt, intended to meet the growing interest of the working class movement in Socialism. Mr. Lang was, nevertheless, anything but a Socialist or a believer in Socialism. When some of his misguided followers took up the cry of Socialisation and proceeded to form Socialisation units, intended to “prepare the people for the coming of Socialism,” Lang came down on them like a ton of bricks. He ordered the disbandment of the Socialisation units and threatened the expulsion of those who refused to obey.

“The people to whom we must appeal have no interest in learned dissertations on Socialism” he sneered at the 1933 Metropolitan Conference of the Labor Party.

Lang was no Socialist, and no revolutionist, he wasn’t even a “repudiationist.”

Mr. Lang has lately appeared in a new role – that of a strike organiser.

He strongly supported the strikes of the Waterside Workers, Miners, Textile Workers and other sections of the workers.

During the Waterside Strike his closest followers were calling for the defeat of the Curtin Government and were intent on disrupting the war effort. Lang is not concerned that we are engaged in a great People’s War against Fascism, that the working class, who have most to gain from a victory over Fascism, must avoid, as far as possible, any action or struggle that will disrupt the war effort and limit production. He is not concerned with strengthening the Labor Movement and rallying support for the Curtin Government. Like Menzies, Lang wants Curtin thrown out of office. He wants to destroy the present Federal Labor Government as he did the Scullin Labor Government in 1931.

Lang was not always in favour of strikes. When he was head of the N.S.W. Labor Governments of 1975-27, and 1930-32, he raised the slogan “Don’t Strike with Labor in Power!’ Every strike was denounced. Lang went further, he helped to break strikes. When the shearers in Queensland struck in December, 1930, against wage cuts, the pastoralists and the A.W.U. bureaucracy organised “scabs” from N.S.W. The workers of this State objected and the Lang Government provided police to protect the “scabs” and land them safely in Queensland.

Again, when the meat workers at Aberdeen, N.S.W., came out on strike against speeding up and wage cuts, they organised mass picketing to prevent “scabs” from taking their jobs. The Lang Government sent the police to disperse the pickets and protect the “scabs.”

Both the shearers and the meat workers were defeated.

The way in which Lang dealt with the unemployed, however, was even more abominable.

Barely a month after he was elected to office, in November, 1930, the unemployed, having obtained official permission, marched to Parliament House in order to interview Lang with the object of achieving some easing of their terrible plight. Lang, who had a strong force of police present, refused to see them and the police were ordered to disperse the marchers, which they did with batons, boots and fists. Thereafter the unemployed were attacked, beaten and gaoled in Port Kembla, Bulli, Sydney, Newcastle and many other centres.

This was also a time when many families, unemployed and unable to pay rent out of their miserable dole, were being evicted from their homes.

Whole families were being emptied out of their homes onto the streets, with no place to go. J. T. Lang, that “bowelless,” estate agent and landlord, an now the Labor Premier of N.S.W. showed not the slightest interest in their plight. He was probably too busy with tin hares and fruit machines.

The unemployed to protect themselves, were forced to organise. They claimed the right to live and to work and to be provided with shelter. They demanded of the Government that a rent allowance be provided in addition to their miserable dole. They were determined to fight for their rights and to prevent evictions.

Anti-eviction committees were formed and were successful in preventing many evictions. But landlords and tent collectors were determined to have their way and Lang stood behind them.

At Bankstown, on June 17th, 1931, a family was to be evicted. The unemployed were determined to prevent it. The Lang Government despatched a large posse of police to disperse the anti-eviction committee and to ensure that the eviction was carried out. The police acted with great brutality. They fired on the workers, batoned them into insensibility and threw a number into gaol.

Two days later another eviction took place at Newtown in similar circumstances.

In the days when he was in power Mr. Lang was a Consistent opponent of strikes and of organised unemployed resistance to evictions. This is why his strike-organising activities to-day are so suspect.

Next to bankers, Lang’s pet aversion was “imported Governors.” He never ceased denouncing them and never failed to use them to advantage. Whenever he was about to push through some particularly reactionary piece o legislation, or engage in some new betrayal of Labor policy, Lang could be depended upon to roundly condemn bankers, Governors arid, also, the Upper House. He always believed in blaming others for his own crimes. This is a propaganda trick that Hitler and many other reactionary demagogues have exploited with success. What his followers could never understand about Lang, however, was how, after his tirades against Governors, and his threats of what he would do if they pressed him too far, he so tamely submitted to them whenever they stood him up. In 1927, Lang, after an interview with Sir Dudley de Chair, the Governor of N.S.W., agreed to a dissolution of Parliament, although his Government had still a year to go. Sir Dudley de Chair was merely the voice of Bavin and other reactionaries, yet Lang abjectly submitted. He resigned without consulting the Labor Party Caucus, Cabinet or Executive. The Labor Party was defeated at the ensuing elections ‘and Lang was relegated to the position of Opposition Leader until November, 1930.

Then there was that matter of Governor Sir Phillip Game in 1932. But before dealing with Lang’s dismissal by Governor Game, the only Australian Premier to accept dismissal by a Governor, let us consider the general Labor Party position.

Early in 1931, Lang, who, by this time, completely dominated the Labor Party machine in N.S.W., engineered the expulsion of E. G. Theodore from the Labor Party.

E. G. Theodore, or “Mungana Ted,” as he is known on account of the Queensland land scandals he was so richly associated with, was Treasurer in the Scullin Government. That he should have been emptied out of the Labor Party was nothing to be sorry for, because Theodore was, and remains, an outright enemy of the working class. He should have been expelled long before. Lang did not expel Theodore because of his treachery to the working class, but because he stood in his, Lang’s, way of achieving his dominating ambition to enter Federal Politics and become Prime Minister. Theodore also aimed at the Prime Ministership. Lang, who is a complete mediocrity, has always resorted to expulsions to deal with anyone who might prove a challenger to himself, or who stood in the way of the achievement of his ambitions.

A typical Lang provocation, the expulsion of Theodore was but a preliminary step in the defeat of the Scullin Government, which Lang believed to be necessary if he was to enter Federal politics and become Prime Minister.

The Labor Party was split from top to bottom by Lang following this action against Theodore. Two Labor Parties existed, the Lang Labor Party, nd the Federal Labor Party. Since then Lang has split the Labor Party gain and again but never with such sinister purpose as in 1931.

Following the split a Lang Labor group was formed in the Federal Parliament, led by Beasley. (Beasley recently broke with the Lang clique).

The Lang group in the Federal Parliament was deliberately disruptive and obviously out to bring about the downfall of the Scullin Labor Government, just as Calwell and a group of Lang followers are out to bring about the defeat of the Curtin Government to-day.

In November, 1931, the Scullin Government was defeated by a joint vote of the Lang Group and the U.A.P.-U.C.P. members led by Lyons. What happened was this.

The Lang “inner group” decided to get rid of the Scullin Government. A plan was worked out for the Lang group in the Federal Parliament to move a vote of no confidence in the Labor Government on the grounds that Theodore was showing favouritism to his own electorate in the allocation of unemployed relief money. Agreement was reached with Lyons, the opposition leader, on this issue and when the vote was taken the Labor Government was defeated and forced to resign.

The Federal elections took place in December. The Labor Party was split. Lang, although not a member of the Federal Parliament but having designs of getting there and becoming Prime Minister, thrust himself into the forefront in the elections, disrupted the whole of the Labor Party campaign and was responsible for the most catastrophic defeat inflicted on the Labor Party since Federation. Lyons came to power. The Labor Party became His Majesty’s Opposition and remained there for the next ten years, until the Curtin Government was formed in October 1941.

When the Scullin Government was formed in 1929, and the Lang Government in 1930, the hopes of Labor were high. The rank and file of the Labor Movement were saying “our turn has come at last.”

Lang blasted their hopes and made their “turn” a mockery and a farce.

In 1931, when the Lang Group joined with Lyons to defeat the Scullin Government, Lang had definitely decided to enter Federal politics. The disastrous defeat of the Labor Party at the polls forced him to postpone his decision. Recently he made another bid to get into Federal Parliament. It was all worked out that he would win, by hook or by crook, the pre-selection for the Federal scat of Reid, held by C. Morgan. just as in 1931 when his moves for Federal honours and leadership were accompanied by the most unscrupulous attacks on the, Scullin Government, culminating in the understanding with Lyons and the defeat of the Federal Labor Government, so, to-day, Lang is engaged in the same disruptive activity. He is the most bitter opponent of the Curtin Government in the Labor Movement. His attacks on the Federal Government are equalled only by those of Menzies and McLeay for the U.A.P. and B.H.P. monopolistic interests.

Lang, in 1943, is as good a second to Menzies as he was to Lyons in 1931.

It was only a few short months after he had ousted the Scullin Government that Lang himself was dismissed from office. Lang had done everything demanded by Sir Otto Niemeyer, the representative of the Bank of England, who visited Australia in 1930. He had reduced wages and salaries in accordance with the decisions of the Premiers’ Plan, increased the taxation of lower incomes, put the unemployed on a starvation ration and suppressed the resistance of the Trade Unions and organised unemployed. In short, he had placed the main burdens of the crisis on the backs of the workers, farmers and middle classes.

The ruling class now resolved to get rid of him as he had served his purpose and his demagogy was arousing the workers to action. The Lyons Government, which Lang had brought to office, passed legislation enabling it to impound N.S.W. income to meet overseas interest payments. Lang replied by the most demagogic attacks on all and sundry. “If they force me far enough I will go the whole-hog,” he threatened. He urged the workers to “stand by him.” The “revolution is here,” he shouted.

Then came the anti-climax.

Lang had issued an order instructing public servants not to hand over the funds of the State Government to the Federal Government. On May 13th, 1932, the British Governor to N.S.W., Sir Phillip Game, summarily dismissed the Lang Government from office for “instructing public servants to violate the Federal Law.”

All that Lang had to say when the news reached him that Governor Game had wiped aside the constitutional rights of the people of N.S.W. and dismissed the Government they had elected was: “Thank God, I am a free man.” He walked out of his office, got into his car, and drove to his Hawkesbury farm and was not beard of for days after. He did not consult Cabinet, Caucus or the Labor Party Executive. The “big, strong man,” when the test came, was as weak and pliable as putty. All his talk of fight meant nothing. When he next appeared before the public, however, it was to tell the workers they had “let him down” – he, the man who wouldn’t fight!

In the elections of 1930, Lang was returned with the largest majority ever. In the elections in June, 1932, following his dismissal from office, Lang led the N.S.W. Labor Party to its worst defeat.

Lang has formed two Governments in N.S.W., neither of which lasted more than two years. He led the N.S.W. Labor Party for sixteen years, 12 of which were spent in opposition. He established an all-time record as opposition leader. He proved the best election winner that the U.A.P. has ever had.

Take Lang’s record since 1931. In 1931 he split the Labor Party, ousted the Scullin Government and caused the defeat of Federal Labor at the polls. In 1932 he. wrecked his own Government in N.S.W. and then lost the elections. He lost the Legislative Council referendum to Stevens in 1933. By maintaining the split in the Labor Party and again interfering he won the Federal elections it 1934 for Joe Lyons. In 1935 Lang again led the Labor Party to defeat in the State elections. In 1936 he engineered another split in the Labor Party by expelling five Labor politicians and a whole group of trade union officials and other L.P. members. In 1937, which he described as the “year of great Labor victories,” Lang, who was then advocating his suicidal “isolationist” policy, was again responsible for the defeat of the Labor Party in the Federal elections. In 1938 he lost, as per usual, the N.S.W. State elections. In 1939 he was removed from the leadership of the Labor Party, and from then on the Labor Party regained prestige, won the support of new sections of the people, succeeded in elections and formed, once again, Labor Governments.

But Lang was not content. He engineered still another split in the Labor Party when he organised his “non-Communist.” Labor Party. After faring badly in the Federal elections of 194o, this outfit was disbanded, and Lang scurried back to the Labor Party fold, but only to carry on his disruptive work within the official Labor Party, and to try and worm his way back to the leadership.

His recent expulsion from the Labor Party has not deterred Lang, who now exhorts his followers to capture the next conference of the Labor Party in N.S.W. and to reinstate him, not only in the Party, but in the leadership of the Labor Party.

Following his expulsion from the Labor Party on March 5th, Mr. Lang attended the next meeting of the Labor Party Caucus. The chairman asked him to leave, as not being a member of the Labor Party any longer he was not entitled to attend the Caucus. Lang refused and invited anyone to try and throw him out. The chairman then adjourned the meeting for fifteen minutes. Lang was still there when the meeting re-assembled. The chairman again asked him to leave. Lang got up and left the meeting as quietly as if he had been requested to do so by Governor Game. He then went to the capitalist press and gave them the story.

Lang was never a believer in Caucus meetings, except in the period between 1913-23, before he became leader of the Labor Party, and from 1939 on, after he had been removed from the leadership. Democracy has never had any meaning for him.

When his Caucus began to revolt as it did in 1926, during his first administration, Lang went to the Labor Party conference, which he controlled, and sought its approval to forbid elections that enabled any challenge to his leadership. The rules of the L.P. then provided that any member of the Caucus at a pre-sessional meeting could be nominated and contest the leadership of the Parliamentary Caucas. Lang, through conference, had himself declared leader and put an end to this practice. The L.P. conference made the proviso that the decision applied only to the Parliament then sitting. But it was not to end there. The Lang dictatorship, once established, was maintained. Caucus met ever more rarely. Soon the day came when Lang never bothered to consult Caucus at all. After the disastrous defeat of 1932, when revolt threatened within the Labor Party, Lang attended a stage managed L.P. conference, and was appointed “leader” of the Party. He became the Fuehrer of the Labor Party; independent of Caucus, even of the Executive; Lang was a law unto himself.

Very early in the piece Lang got control of the L.P. Executive and moulded it to his purpose. But even this did not satisfy him. He formed what has become known as the “Inner Group” – a body outside of the L.P. Executive and responsible to no one but Lang. The “Inner Group,” a sort of “brains trust” for Lang, included several people who were not even members of the Labor Party. It was this body, and none other, that for many years decided Labor’s policy in N.S.W. None the less, Lang now writes in the “Century” of the leaders of the Curtin Government: “When I see men who took office as Labor men deliberately denying the Labor policy and platform, then I must say of them – they are not Labor men.” (“Century,” 12/3/43.) His “Inner Group” were certainly not ‘Tabor men” and never had been.

The L.P. Executive, during the ‘Lang regime, was a mere cypher. Although elected by the Labor Party conference, and although it was supposed to he the highest authority of the Labor Party in this State between conferences, the Labor Party Executive took its orders from the Lang “Inner Group” that existed and worked behind the scenes. And woe betide Paddy Keller, the President, or Graves, the Secretary, of the Labor Party, if anything went wrong with the “Inner Group’s” plans. The “Inner Group” decided not only the policy of the Labor Party, it controlled the real finances of the Labor Party as distinct from the relatively small amounts that went through the hands of L.P. Executive officers. No one has ever seen a balance sheet showing the income and expenditure of this “Inner Group.”

Lang had the Labor Party by the throat. He was the all-powerful dictator. The LP. members of Parliament were completely at his mercy. They must do hi% bidding or off would come their heads and bang go their pre-selection. At the 1934 conference of the Labor Party, Mr. Cahill, N.S.W. Labor Party member, said that “the fifty-four Labor members in the last State Parliament supported Mr. Lang because they were not game to do otherwise.”

The politicians became subservient, spineless, hopeless. The L.P. in N.S.W. degenerated. Its representatives in Parliament were of the lowest order, the least inspiring since the L.P. was formed in 1891. The depths were finally plumbed when Lang decided that for the Federal Senate team he wanted not men who had lived and belonged to the labor movement, not men who were respected for their labor beliefs, their loyalty to the working class and their ability, not men at all, but names – names that started with A. They could be dills, traitors or scoundrels, but so long as their names started with A Lang was satisfied.

Pre-selection-ballots, or ballots of any kind, were never of any trouble to the “Inner Group.” Their returning officer once proudly boasted: “When I conduct the ballot just tell me who you want to win and I’ll do the rest!’ Rigged ballots and sliding panels were all part of the “Inner Group” technique. It is no surprise, therefore, that to-day complaints are coming in from all sides about ballot faking and plural voting in the pre-selection ballots now under way. The Lang machine is hard at work and it knows all the tricks there are to be known about winning ballots.

It was inevitable that the Lang method of leadership, “Inner Group” control, and the stifling of democracy within the Labor Party would arouse opposition. To this, Lang replied, as all dictators do, with more ruthless measures, more dictatorial rule. From 1933 onwards expulsions from the Labor Party increased and L.P. branches had their charters withdrawn.

But the unions were also becoming hostile and this was dangerous for

Lang, because they controlled the radio station 2KY, and held a majority of the shares in the “Labor Daily” newspaper.

The Lang “Inner Group” decided that, in view of the growing opposition in the unions, the time had come to take complete control of these two great propaganda organs and eliminate the unions.

At the beginning of 1936, the “Inner Group” brought forward an ingenious proposal to form a company to control 2KY. They were not concerned that 2KY was quite satisfactorily run by the N.S.W. Trades and Labor Council, and was available for the use of the Labor Party at any time. Their plan for a new company provided for seven directors, as follows: Two directors to be appointed from the “Labor Daily” Board of Directors, one director to be appointed by the Labor Party Executive, and four by the Trades and Labor Council. The “Labor Daily’ and A.L.P. Executive representatives would be handpicked Lang men, and to ensure that the Labor Council representatives would be O.K., the Lang organisation packed the Labor Council meeting to railroad this proposal through. It was also proposed that in return for the ‘Tabor Daily” and Labor Party Executive comprising part of the company, the Labor Party, or in other words, the “Inner Group,” would find £2,000 additional capital. Now 2KY radio station had a potential value bordering on £100,000 and an average yearly profit of £8,000. For this masterly company idea and a mere £2,000, Lang and his cohorts on the “Inner Group,” were going to get this rich prize, the property of the Trade Union movement. Fortunately, although Lang packed the Trades and Labor Council and believed he had everything sewn up, many of the delegates he banked on supporting him were so dismayed with this brazen piece of daylight robbery, with the plan to pilfer Trade Union property, that they voted against him and 2KY remained a Trade Union station.

Equally ingenious was the scheme to oust the Trade Unions from the ‘Tabor Daily.” The “Inner Group” proposed to alter the “Articles of Association” of the ‘Tabor Daily” to permit of the publishing of a Sunday newspaper. Under their scheme 20,000 new shares were to be issued. The conditions of the new share issue were to be such that the shares could be had on even a 3d. call and carry the same voting rights as the fully paid-up shares held by the unions. The “Inner Group” had manipulated it so that the majority of these new shares would fall into the hands of Lang and his supporters, giving them complete control of the “Labor Daily.”

The union shareholders were awake, and although Lang believed he could muster a majority of votes for this racket, the shareholding unions turned him down.

Then Lang played the dirtiest trick of all. Back in 1931, when the ‘Tabor Daily” was in financial difficulties, the Labor Party Executive was approached by the unions for financial assistance. They were referred to Lang and be, after terms satisfactory to himself were reached, agreed to advance, on behalf of the L.P., £13,764/6/4, for which a debenture was taken out in the name of J. T. Lang. The money came from the L.P. funds collected from unions, LP. members and other sources. Lang agreed to invest the money in the ‘Tabor Daily” on condition that he got a firm hold on the paper and five per cent. interest. At that time, 1931, Lang was denouncing far and wide the “iniquitous” interest payments to bond holders. From the labor movement, however, he made the excessive demand for five per cent. interest.

At the beginning of 1938, after the unions had rejected his fake reorganisational proposals, and when Lang felt that his hold on the “Labor Daily” was weakening, he issued an ultimatum to the unions that they, must pay on his debenture within 30 days or he would sell the paper.

The trade unions had to pay to Lang personally £17,889/17/11, which included £4,125/11/7 interest, even though the money invested in Lang’s name belonged not to Lang, but to the Labor Party. When it comes to companies, shares, debentures and interest, Lang certainly knows his stuff.

Lang’s demand for payment on the debenture with interest. scaled the fate of the “Labor Daily,” or the “Daily News” as it was afterwards called. The paper never recovered financially from the blow.

Lang smashed the paper established by the trade unions of N.S.W. just as he smashed the Scullin Labor Government, and split and disrupted the labor movement.

In the struggle that developed over the attempt of Lang to get control of 2KY and the ‘Tabor Daily,” the opposition to his leadership came to a head. The “Inner Group” had over-reached itself. The unions and L.P. leagues demanded a change in Labor Party leadership and the restoration of democratic control within the organisation. Lang was a dictator and there is no place for dictatorship within the labor movement. Following the defeat of the Labor Party in the Federal elections of 1937, for which Lang was mainly responsible, a conference of unions was held on November 18th. The conference, consisting of 350 delegates from 70 unions with 250,000 members, repudiated the Lang “Inner Group” and pledged itself to remove them from their dictatorial positions in the labor movement.

Another conference was held on January 22nd, 1938, representative of union and L.P. branches. Four hundred delegates attended. The conference set up a Provisional Executive that included the expelled politicians. It was this movement that ultimately succeeded, with the help of the Federal Executive of the L.P., in removing Lang in 1939.

Lang, who substituted dictatorship for democracy and intrigue, factionalism and the pursuit of personal ambition for labor principles, discovered that in the end democracy will assert itself, the voice of the rank and file will be beard, and that in the face of these processes, dictatorship must inevitably fail.

Mr. Lang was always the opportunist. He never started from the fundamental principles of the labor movement in deciding policy. He is, as a matter of fact , quite incapable of such an approach. Thus, when the struggle against Fascism loomed large in the international arena following the rise of Hitler, when the working class of all countries were in need of unit,- on a national and international scale in order to struggle successfully against Fascism, Mr. Lang, in this country, took up a pro-Fascist attitude and continued his disruptive activity in the labor movement.

When Mussolini attacked Abyssinia in 1935, an amazing somersault was performed by the Lang machine. On August 20th, 1935, following the invasion of Abyssinia by the Fascist hordes, the “Labor Daily,” the policy of which, at that time, was entirely under Lang control, wrote: “It now remains to be seen whether France is prepared to co-operate in maintaining the covenant of the League of Nations to cheek an act of naked aggression.”

In an editorial on August 22nd, it again wrote: “Any conflict similar to that of 1914-18 is unthinkable, but the rape of Abyssinia would represent a direct challenge by Italy to the entire system of collective security that must be met by effective application of economic and financial sanctions.”

Brave words from the Lang machine. “Collective Security,” the “League of Nations,” “Sanctions” – it seems unbelievable to-day. It was too good to last. Mussolini and Hitler raged against collective security and Lang joined in the chorus with them.

On September 4th, 1935, Lang gave a speech and repudiated everything the “Labor Daily” had written a few days before. He bitterly attacked the League of Nations, he denounced collective security, and sanctions, and demanded a Policy of “neutrality.” Signor Gayda, Mussolini’s chief propagandist, was bleating over the wireless, “Sanctions mean war,” and Lang took up the same slogan here.

In 1936 the Fascist uprising took place in Spain. Franco was supported by Mussolini and Hitler in his efforts to overthrow republican Spain and smash the labor movement. The Spanish Communist Party and the Socialist or Labor Party of Spain, the brother party to the Australian Labor Party entered into a united front against Fascism, the chief enemy of labor.

working class in all countries, in their own interests, as well as in the interests of the greater aims of the working class, supported the gallant Spanish people. Chamberlain in Britain and Lyons in Australia were for a policy of “non-intervention,” which really meant to give the Fascist powers – Germany and Italy – a free hand to strangle the democratic republic of Spain.

Lang, also, in defiance of all working class principles, came out for the policy of “non-intervention.” While he demanded that the Australian workers take “no sides’’ in the Spanish conflict, his stooge, in the Executive of the Labor Party, Paddy Keller, took up regular collections of money for France Spain.

During the 1937 Federal elections, Lang actually discovered what he called a “Lyons-Litvinoy-Communist plot to involve Australia in war.” The Communist Party was described as a “war monger,” because it advocated an understanding between the British and Soviet peoples and a collective front of all democratic peoples to prevent the outbreak of war. Lang fought against any such collective security pact. So did Hitler, Mussolini and the Japanese military Fascists.

When China was attacked by the Japanese gangsters in 1937, the working class movement of Australia called for a boycott of Japanese goods and the stoppage of exports to Japan.

In 1938 the Port Kembla waterside workers, in a magnificent gesture of international solidarity and opposition to war, refused to load pig iron for Japan: The Japanese Consul protested. Lyons attacked the wharfies and Menzies was sent post haste to Wollongong to put an end to the dispute.

Lang joined this gang, the Japanese Consul, Menzies and Lyons, in attacking the Port Kembla waterside workers. He demanded an end to the boycott Japanese goods campaign, the loading of the pig iron, and no further “provocation to Japan.”

The Lang propagandists had never a word to say against Fascism, against Hitler or Mussolini. They saved all, their hatred and spleen for the great workers’ Socialist republic, the Soviet Union, and its leader, Stalin. The ‘Tabor Daily,’.’ while Lang was in control, and subsequently the “Century,” retailed all the Trotskyite filth and capitalist lies about the Soviet ‘Union.

When, in 1939, the Soviet Government, after all its efforts to create a system of collective security, which Lang bitterly attacked and fought against, failed, decided to enter into a non-aggression pact with Germany, in order to gain time to more effectively prepare for the inevitable war with Hitler, Lang simply frothed at the mouth.

The Lang policy of opposition to collective security, of “isolationism” had not because Lang supported it, but because it was the policy of Hitler, Mussolini, Chamberlain and Daladier. That policy resulted in the war. The Soviet policy could have prevented the war. Nevertheless, although the policy Lang supported had unfortunately prevailed, his paper, the “’Century,” now began to shout that the Soviet Union, by, concluding the Pact with Germany, had caused the war. But they did not stop there. During the Finnish-Soviet war, which broke out at the end of 1939, Lang’s paper gleefully published all the Whiteguard lies disseminated by Baron Mannerheim and the pro-Fascist Finnish Government. The “Century” joined in, the campaign that was to prepare the way for war on the Soviet Union and the switching of the war. With a number of other papers at the beginning of 1940 it was declaring that the Allies, Britain and France then, would be better, off if they declared war on Soviet Russia.

Lang was always a bad prophet, but he was at his worst when dealing with the Soviet Union. Who, to-day, would say that Britain would be stronger if she were, ‘at war not only with Germany and her Allies, but with the Soviet Union as Well?

Lang pursued a consistently pro-Fascist policy. He was for Australian “Isolation,” an anti-working class policy. “Isolation” meant a renunciation of the responsibilities of the working class in the struggle against Imperialist war and Fascism. It meant to abandon the Spanish and Chinese people so valiantly fighting against Fascism; it meant to grant every facility for the Fascists to carry out their bloodthirsty and aggressive designs.

To-day as an “anti-conscriptionist,” as an opponent of the Curtin Government, as a vicious critic of every war measure of the Government no matter how essential it is, Lang is pursuing the same policy. His policy helps none but the Axis powers. He is lined up with the Fascist enemies of labor against the progressive anti-Fascist people.

Such is the sordid story of J. T. Lang. That such g man could for so long mislead and disrupt the Labor movement can be accounted for only because of the immaturity of the working class movement, of the insufficient understanding of the basic principles and aims of labor.

The labor movement must beware of those who climb on the backs of the, workers only to give rein to their personal ambitions, who set aside democracy and pursue an opportunist policy.

Leaders in the Labor movement must be judged by their attitude to the fundamental principles of labor; they must remain leaders only so long as they adhere to those principles.

Lang is out. He is expelled from the Labor Party and is unwanted by any other working class organisation. He must be kept out. But there are many others like him – the Calwells, Fallons and others who play the same treacherous game, who subvert the principles of labor.

They, too, must be cleaned, out of the labor movement.