‘International Workers Aid’ 1921–37

Comintern Global Solidarity in Action

Part 5 of a nine-part series on the Communist International’s auxiliary organizations.

By John Riddell

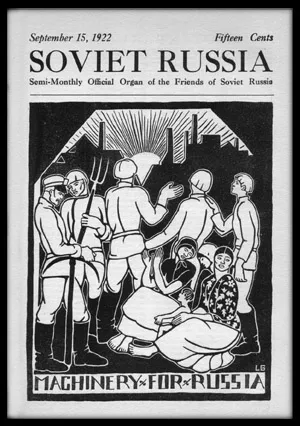

The International Workers’ Aid (IWA), also known by

its Russian acronym MRP, was launched as an emergency campaign to help

alleviate a widespread famine in Soviet Russia.

its Russian acronym MRP, was launched as an emergency campaign to help

alleviate a widespread famine in Soviet Russia.

Founded in Berlin on September 12, it grew into a global movement seeking not only to assist economic construction in the Soviet republic but to bring aid and lend political support to embattled and oppressed working people around the world.

Arguably the Communist International’s broadest and most successful global initiative, the IWA showed the potential of global solidarity aid programs independent of capitalist governments, an approach subsequently exemplified above all in the renowned worldwide solidarity efforts of revolutionary Cuba.

The IWA’s director, Willi Münzenberg, estimated its global membership in 1926 at 15 million adherents, organized in sections in every European country, the USA, India, China, and many other countries.

Comintern Initiative

The IWA was initiated at the International’s Third World Congress by a letter to Münzenberg from Comintern President Grigorii Zinoviev.[1] <#_edn1> Münzenberg headed the movement and was its driving spirit until its dissolution in 1935.

Reports of the Russian famine aroused deep sympathy among populations abroad, such that even bourgeois agencies launched relief efforts. By comparison, the IWA’s achievements, although drawing support only from a wing of the workers’ movement, were impressive. In December 1922, Münzenberg reported that during the famine the IWA had supplied food for more than 200,000 Soviet citizens. It employed at one point 30,000 Soviet workers in factories under its management, shipped 30,000 tons of relief goods, and contributed funds equivalent to half of what the Soviet government invested during that time in rebuilding heavy industry.[2]

United Front

Although based on global Communist movement, the IWA reached out far beyond it to gather support. Münzenberg accurately identified it as the first successful effort to set up a functioning united front.[3] <#_edn3> Although the German Social Democracy barred its members from participating in 1923, the IWA reached out broadly, recruiting the support of significant numbers of political figures, artists and intellectuals.

During the 1923 economic breakdown in Germany, the IWA aided German workers through soup kitchens, strike funds, and children’s homes. (/Inset: Willi Münzenberg 1889-1940/)

The IWA can also be viewed as a pioneer Non-Governmental Organization. By taking up the cause of victims of colonialism, the IWA helped redefine the word “international” to apply not merely to peoples of the West but to those of the entire world, and particularly to victims of colonialism.[4]

The IWA translated this principle into action in response to the “Shanghai incident” in China on 30 March 1925, when police in the foreign-controlled “International Settlement” within Shanghai unleashed murderous gunfire against anti-colonial demonstrators. The slaughter in Shanghai unleased massive protests across China. The IWA extended this movement into Europe and beyond, raising the slogan, “Hands Off China.” For the first time in history, working people in both Europe and the colonized nations joined in a common anti-colonialist campaign.

Anti-Imperialist Unity

The IWA broadened these efforts into a permanent world movement, which found expression in the IWA’s historic world conference against imperialism of 184 delegates from 34 countries in Berlin on 10 February 1927. Subsequently, the IWA structured an international solidarity movement: see on this blog “The League against Imperialism (1927–37): An Early Attempt at Global Anti-Colonial Unity. ”[5]

The International Workers’ Aid did not hide its Comintern sympathies, proclaiming that it was founded on Lenin’s initiative and affirming its partisan stance in support of the Soviet Union. However, the IWA had no organizational link with the Comintern. Comintern historian E.H. Carr has noted, “Almost alone among the [Comintern] auxiliary organizations, it retained its headquarters abroad, and escaped the day-to-day control of the Comintern bureaucracy.” As evidence of this autonomy, the IWA always treated fascism as a central enemy of the working class, even when Comintern policy shifted away from that focus.[6] <#_edn6>

Among the well-known intellectuals supporting the IWA were Albert Einstein, Heinrich and Thomas Mann, Käthe Kollwitz, Anatole France, Arthur Koestler, and Henri Barbusse.[7]

Meanwhile, Münzenberg expanded the IWA’s scope to embrace an impressive apparatus for solidarity and socialist education, based on mass-circulation magazines and films.

When the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, they quickly demolished the IWA’s base in Berlin. Münzenberg and his colleagues continued their work abroad, but their efforts were undercut by policy reversals in the Comintern.

Efforts to establish a united front against fascism, which had been so disastrously abandoned in 1928, were restored by the Comintern’s Seventh World Congress in 1935. The new Comintern policy, however, encompassed a search for alliances with supposedly anti-fascist forces in the imperialist ruling class.

Dissolution of IWA*

This orientation conflicted with the IWA’s anti-colonial campaign. Only a few months after the Seventh World Congress, the IWA was closed down by a confidential decision of Communist authorities in Moscow. The decision is variously attributed to the Comintern Secretariat or to the Soviet Communist Party Central Committee.[8] <#_edn8>

In the years following the 1935 world congress, Münzenberg turned against Comintern policies, particularly with regard to the murderous Stalinist purge trials that struck down a significant proportion of the Comintern’s leading cadres. Formally expelled from the Communist movement in 1939, he continued his anti-fascist work, notably opposing the Stalin-Hitler pact of August 1939. In mid-1940, during the Nazi invasions of France, Münzenberg was killed by unknown assailants while fleeing the German armed forces.

Although the IWA and its central leader had now passed from the scene, the IWA’s spirit found partial expression during the years that followed in two quite different and massive movements: wartime anti-fascist resistance in Europe and the prolonged anti-colonialist uprising in Asia and Africa.

For a selection of articles on the Marxists Internet Archive, by Willi Münzenberg on International Workers’ Aid, see here.

Notes

[1] John Riddell, ed., /To the Masses: Proceedings of the Third Congress of the Communist International, /Leiden/Chicago: Brill/Haymarket Books, 2015, p. 41.

[2] Riddell, ed., /Toward the United Front: Proceedings of the Fourth Congress of the Communist International,/ Leiden/Chicago: Brill/Haymarket Books, 2011, pp. 40, 640.

[3] Quoted by E.H. Carr, /The Bolshevik Revolution 1917–1923/

[4] Tilmann Siebeneichner, review of Kaspar Braskén, /The International Workers’ Relief, Communism and Transnational Solidarity. Willi Münzenberg in Weimar Germany(Palgrave Studies in the History of Social Movements, /in /German History/, vol. 34 (3) (2016, pp. 504.

[5] See also Fredrik Petersson, “Hub of the Anti-Imperialist Movement: The League Against Imperialism and Berlin, 1927-1933 ,” /Interventions (London, England)/ 16.1 (2014): 49–71.

[6] Kaspar Braskén, /The International Workers’ Relief, Communism, and Transnational Solidarity: Willi Münzenberg in Weimar Germany/ , Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, p. 6; E.H. Carr, /Socialism in One Country 1924–1925, /vol. 3, p. 981

[7] Braskén, op. cit.

[8] See Wikipedia, “Workers International Aid,” English edition, which sources to Branko Lazitch and Milorad M. Drachkovitch, /Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, / Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1986; p. xxix. See also the German edition, which sources to Babette Gross, /Willi Münzenberg, /Stuttgart 1967, pp. 287f.