† OTHERS INCLUDE Homeywell/GE, Siemens, Univac, Burroughs, CDC, NCR

Chris Harman Archive | ETOL Main Page

From International Socialism (1st series), No.48, June/July 1971, pp.6-10.

THE Common Market has become one of the central political issues in Britain in the last few months. Support for entry has become the rallying cry for the main body of the Conservative Party, the Confederation of British Industries and important right wing figures inside the Labour leadership. Opposition to entry has become a key point (and in some cases the key point) in the programme of the established left in the Labour movement, and more recently of the Labour Party itself.

But knowledge as to what the Common Market really implies is much less frequently found, particularly among the left. Opposition often seems to have little to do with the realities of how the European Economic Community (EEC) has really operated over the last decade. What is the Common Market in reality? And what should the attitude of the left to it be?

The Common Market is essentially what its title says it is – a business arrangement, an agreement between different capitalist ruling classes, relating to the way in which they organise their markets.

Underlying the turn towards acceptance by the different powers of such a scheme was their common experience in the half-century up to 1945.

Each had discovered in the most damaging and harrowing ways that the scale of capitalist production could no longer be contained within narrow national boundaries. The monopolies and cartels that dominated each national market found that to compete internationally they had to spread their scale of operations beyond state boundaries. But this meant clashing with rival capitalist enterprises operating from within other states. In the last resort such conflicts could only be resolved by the military forces which national blocks of capital had at their disposal.

The politicians of Europe were coming to a dim awareness of what the classical Marxist theorists of imperialism had grasped during the First World War:

‘When competition has finally reached its highest stage, when it becomes competition between state capitalist trusts, then the use of the state power and the possibilities connected with it begin to play a very large part ... With the formation of state capitalist trusts competition is almost entirely shifted to foreign countries ...Whenever a question arises of changing commercial treaties, the state powers of the contracting groups of capitalists appear on the scene, and the mutual relations of those states is reduced in the final analysis to the relations between their military forces ...’ [1]

By the 1930s the stage had been reached in which it was no longer possible for the rival capitalist states in Europe to coexist without being driven inexorably to military conflict. For French capitalism, the precondition for survival was the confining within restricted boundaries of the sphere of operation of German big business. For German industry, survival meant physically eliminating frontiers by extending the Reich and incorporating the industry of Austria, Czechoslovakia and finally most of Europe under its control. Out of such equations came the holocaust of 1939-45.

Continental Europe emerged from the Second Imperialist War battered and devastated. Industrial output in 1947 was only 27 per cent of its pre-war total in Germany, 66 per cent in Austria, Italy and Greece, and remained below pre-war levels in France and the Netherlands, although the population had grown eight per cent. The result was high levels of unemployment, continual inflation, and wide ranging social discontent. [2] The post-war wave of working-class radicalism was held back by the combined efforts of Stalinism and Social Democracy, who collaborated in the French and Italian governments. But in a situation of social crises it could easily revive.

The European bourgeoisie had somehow to get their economies functioning again if they were not to face either a Russian takeover or the development of genuinely revolutionary movements. They feared both. And their fears were shared by the American government. In 1947 a policy planning body of the us State Department concluded:

‘The present crisis (in Europe) results to a large part from the , disruptive effects of the war ... The Communists are exploiting the European crisis and further Communist success would create serious dangers for US security ... American effort in and to Europe should be directed ... to restoration of the health and vigour of European society ...’ [3]

The us government was prepared to dole out through Marshall Aid the funds’ needed to put European capitalism back into a viable condition. Its problem was that in doing so it was likely to recreate precisely the forces that had produced the Second World War. If Europe remained based upon rival national firms tied to national states circumstances of the interwar years seemed likely to be resurrected. And so the us tried to persuade the different governments of Europe to plan the reconsolidation of capitalism on some sort of continental wide basis.

‘The programme this country is asked to support must be a joint one, agreed by several European nations.’ [4]

The chief administrator of the Marshall Plan, Hoffman (who was also head of the Studebaker Corporation) made the point even more forcefully in an important speech to a conference of the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation in October 1949. [5]

In the following months the European powers responded to this pressure by a series of measures that facilitated trade between them. Tariffs were cut, quota restrictions reduced and the beginnings of a multilateral trade system built up.

A year later the first moves towards what was eventually to be the Common Market took place. The French government announced its willingness to join with the other European states in order to provide a single framework for the coal (then the principal fuel) and steel industries of Europe to operate within. Behind this move lay a desire for German economic revival as a necessary bulwark against Russian invasion combined with a fear of German dominance. The coal and steel industries were those most sharply clashing with national boundaries – no single European country had within it the necessary balanced supplies of iron ore and coking coal for steel production. The Coal and Steel Community would ensure that such supplies could be obtained without any recourse to military intervention. A free market in these goods was to be established and any one country would be stopped from achieving a monopoly position. The French plan was accepted by the five other powers (Germany, Italy, Holland, Belgium, and Luxemburg – henceforth to be called the ‘five’), and began to take effect in 1953.

The Common Market was agreed upon three years later as an extension of the principles of the Coal and Steel Community to the whole range of industrial and agricultural products.

Basically the aim of the Common Market was two-fold.

1. Firstly, it was to be a ‘customs union’ – in other words, barriers to the free marketing of the goods of any of the countries in any of the others were to be eliminated, while each would impose identical obstacles to the import of goods from outside the Common Market. Producers from all the member countries would be able to compete on equal terms in a single market of supranational proportions. In this way the traditional limitations on the development of each national European capitalism would be overcome short of military conflict.

As regards industry, such proposals created difficulties. But they did not seem insuperable. In so far as positive intervention was needed by any supranational agency, it was to ensure that the different states did not give unfair advantages to national industry through methods other than orthodox tariffs and quotas, e.g., through hidden subsidies and so on.

Agriculture, however, presented a much greater problem. For a whole variety of reasons the conditions and costs of agricultural production vary enormously from country to country. Free trade in agricultural products would have meant the immediate driving out of business and impoverishment of millions of small farmers, particularly in France. The political and social consequences would have been explosive.

Finally a solution to this problem was arrived at. There was to be planned intervention in the market for agricultural goods by a central body, the European Commission. This would start buying such goods if the market price began to fall, so as to keep the price up and provide a reasonable income for the individual farmers. At the same time, there would be a surcharge on any such goods imported from outside the Common Market area so as to raise their price to that guaranteed to local producers.

What this really meant was that the consumers in some countries – notably Germany – would be helping the French state maintain its political stability by subsidising its peasants. The German ruling class was prepared to accept such an arrangement, because it was convinced that it would easily outweigh the cost to itself by its ability to sell industrial products in the French market. As it turned out, however, its losses were often to be greater than its gains. Because of political consideration

farm prices were always set at such level as to lead to a massive overproduction of produce that nobody wanted to buy, and the Commission had to intervene to absorb this excess production at an ever rising cost to the different national exchequers.

|

Cost of Farm Fund |

|

|---|---|

|

|

$ |

|

1962-3 |

38m |

|

1964-5 |

217m |

|

1966-7 |

494m |

|

1968-9 |

2,437m |

|

1969-70 (estimate) |

3,124m |

This has caused increasing resentment among France’s partners, who have tried repeatedly to alter the basis of the fund. 2. The second aim of the Common Market has been to move beyond being merely a unified arena within which different competing national capitalisms compete, to the beginnings of a positive integration of the rival capitalist classes. What is foreseen is the emergence of European, rather than French, German, etc, firms, working within an overall framework provided by a European Commission whose powers grow until it becomes the framework for the state structure of a Eureopean superpower.

Such schemes for eliminating the traditional rivalries in Europe lacked one important element. Britain’s rulers were unable to bring themselves to join in the plans of the Six when the Market was formed.

There has been a tendency since for commentators to blame this decision on the myopia of one or other set of politicians. But at the time there was near unanimity about its wisdom. The ‘Commonwealth’ was still of major importance for British big business’s profit making. It had been a protected market for the products of British industry, with tariff barriers that discriminated against Britain’s industrial competitors for 30 years. In 1951 51 per cent of Britain’s exports went to the Commonwealth, as against only 10 per cent to the Six. To join the Market meant to dismantle the system that made this possible. Tariff barriers would be erected against Commonwealth produce and would invite retaliatory measures against British goods. British big business’s privileged position in its major markets would be eroded. The attitude of the leading firms was expressed quite succinctly by the Federation of British Industries:

‘The UK could not join this common market, for it also involved a common external tariff and to adopt this would mean for the UK the end of the imperial preference system’. [6]

Instead, the Tory government of the time proposed to the Six an alternative – the creation of a free trade area including the Six, Britain, Ireland, Scandinavia, etc. The Six’s external tariff would not apply to Britain, and their industrial (but not agricultural) goods could enter Britain freely. But Britain would still be able to get its food cheaply (which industrialists valued as a way of preventing too much upward pressure on wages) and Commonwealth goods would not be discriminated against.

The Free Trade Area plan failed, however, for a reason that was later to doom to failure the attempts of British governments to get into the Common Market for a 10 year period – French opposition. French big business saw the political advantages of preventing a renewed fragmentation of Western Europe into hostile states. It was prepared to risk the dangers (as it saw them at the time) of competition with more efficient German industry – particularly if it could also obtain a subsidy for French agriculture from German sources. But it was not prepared to face the added risk of British competition – especially, since under the Free Trade Plan British industry would have the advantage of cheap food prices and would make no contribution to solving France’s agricultural problems.

And so the Common Market was established in 1959 with no form of British association. Instead Britain had to make do with a poor alternative – a Free Trade Area of those West European states not in the Common Market.

In the early 1960s the British ruling class did a complete 180 degree turn on its attitude to the Common Market. The Tory government of Macmillan began negotiating for entry, although with certain reservations, in 1961. These were to become increasingly marginal as years passed and as subsequent governments, Labour and Tory, attempted to overcome the French veto and get into the Market. A number of distinct reasons lay behind the new attitude.

1. The influence of the multi-national corporation

The scale of many industrial operations today is too great to be contained within existing national boundaries. The growth of the multi-national firms is the clearest expression of this. A comparison of the largest firms and some medium sized countries gives the following picture:

|

GNP1969 |

|

|

Sales |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Holland |

28.24 |

General Motors |

24.30 |

||

|

Sweden |

27.85 |

Standard Oil NJ |

14.93 |

||

|

Belgium |

22.82 |

Ford |

14.70 |

||

|

Switzerland |

18.82 |

Royal Dutch-Shell |

9.74 |

||

|

Denmark |

13.99 |

IBM |

7.20 |

||

|

Norway |

9.73 |

Unilever |

6.03 |

||

|

Greece |

8.40 |

Phillips |

3.60 |

||

|

Ireland |

3.40 |

ICI |

3.25 |

||

|

(all in thousand million dollars) |

|||||

The multinational firms continue to operate from national bases. But their productive operations are carried on in a number of different countries and integrated into a single international pattern. IBM, for instance, has a range of computers, the 360/40, with memory components manufactured in Scotland, solid logic ones near Paris, boxes’ and peripheral equipment from the Netherlands, Switzerland and Italy.

For such companies national boundaries constitute an increasing irrelevancy, an impediment to their own international planning. Customs barriers make more difficult the free flow of components from country to country. And any trend towards continual revaluations of national currencies makes it impossible to make rational investment decisions. How can Shell, for instance, determine the relative cost of building a refinery outside Manchester as opposed to outside Rotterdam if it cannot foresee with accuracy the relative values of the pound and the guilder?

The Common Market represents for such firms a means for overcoming uncertainties. It enables them (even if they themselves are American owned) to develop their operations on a European scale.

Multinational firms are far from dominating any single capitalist economy. The main markets and the main outlets for investment remain in all countries nationally located. To that extent capital remains overwhelmingly national capital. But the multinationals have come to dominate certain key industries and to exert an influence greater than their size alone might suggest.

In Britain, for instance, they dominate in car production, in petroleum, and in rubber. In chemicals, the trend is increasingly in that direction – British firms in the industry invest more than half as much overseas as in this country. British owned firms get 30 per cent of their profits from overseas operations, [7] while 25 per cent of British exports are by foreign owned multinationals operating in this country. [8] us owned firms, for instance, account for 17½ per cent of exports, although they only employ 6 per cent of the labour force and produce 10 per cent of goods. [9]

Such firms are in a powerful position to influence the political orientation of the ruling class as a whole – although the policies implemented might even be detrimental to the numerical majority of that class.

2. The growing importance of firms that would like to operate internationally

The attitude of the multi-nationals finds backing among a growing number of firms who have reached a size that impels them to seek to operate across national frontiers – both as regards marketing and production – but who have not yet been able to overcome the barriers to this.

‘Far many firms national markets have always been, and will continue to be adequate ... (but) many large firms have reached the point at which further national restructuring is impossible because, of the present scale of the enterprise in relation to the market’. [10]

3. The needs of the technologically advanced sectors

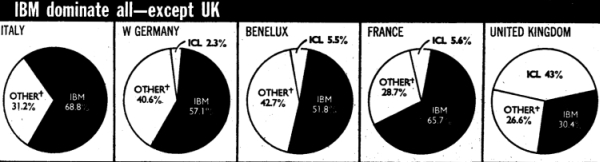

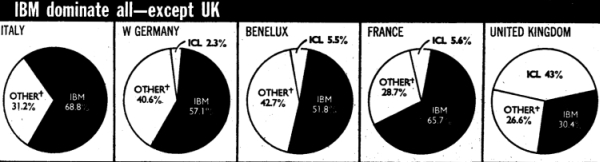

The drive to overcome national boundaries is even greater for the most technologically advanced industries. The European countries individually cannot provide the domestic markets, the capital resources or the government backing needed to survive in international competition. The result is perhaps most graphically shown, in the case of computers, where one American firm dominates in most of Europe, and where most of its competitors are also American.

British competitors believe they can only survive by looking to Europe.

‘It is precisely in the most advanced industries that management leaders with very few exceptions, are most enthusiastic for British entry’. [11]

It has been estimated that whereas ‘old’ industries such as motor car manufacturing begin to acquire ‘economies of scale’ with markets of ten million people, newer industries such as computers need a minimal market of one hundred million. [12]

The American computer firm IBM is able, because of its larger market, to have manufacturing runs five times as large as those of its British competitor, ICL; its productivity is consequently twice as high. [13]

|

|

† OTHERS INCLUDE Homeywell/GE, Siemens, Univac, Burroughs, CDC, NCR |

The amounts of capital needed for development in such industries ara also vast. In the mid-’sixties IBM produced a complete new range of third generation computers, the system 360, which used a high proportion of micro-circuits and made obsolete former transistor based models. It took an investment of 4.5 billion dollars – more than double what it cost the American government to develop the nuclear bomb before Hiroshima. Such resources are not available within the individual countries of Europe.

‘Successful European industrial policy will require very substantial capital resources, which will only be forthcoming through a mechanism which permits its savings to be mobilised on a continental scale’. [14]

Finally, and most importantly, the technological industries are dependent for their development upon massive government aid and contracts. It is since the launching of the first satellites in the late ‘fifties that the technological gap between Europe and America opened up. Government spending (i.e. arms and militarily motivated space programmes) accounted for 64 per cent of total US expenditure on research and development (R and D) in 1963-4. It sustained the total at 23,685 million dollars, or 3.1 per cent of the Gross National Product.

The European governments singly cannot compete with such massive sums. Britain has by far the largest R and D effort of them all. It was spending 2.3 per cent of its GNP in this way in 1963-4, as opposed to only 1.6 per cent for France and 1.4 per cent for Germany. Yet the total sum spent in Britain was less than a tenth of that spent in the us. [15]

Each of the European governments is moving in to provide guaranteed markets and to underwrite research costs in fields like that of computers. The French firm CII receives £12m a year in government grants; the German computer firms, chiefly Siemens, £10m; the British ICL £4m, which is likely to increase. But these figures do not begin to measure up to what the us firms gain as a by-product of defence expenditure. Only support by the combined efforts of several European states could do so. This explains the CBI’s demand that:

‘Industry must intervene vis-à-vis governments to ensure that all government action in this area is well designed, timely and consistent with sound strategies for technology and industry in Europe’. [16]

The Common Market is seen as leading towards the creation of a state of multi-national dimensions capable of providing the resources needed to stand up to American competition. However, it does not at all follow that such hopes can be realised.

4. The so-called ‘dynamic’ effects of entry

A fourth reason is always given when supporters of capitalism argue about the merits of entry. This concerns the so-called ‘dynamic’ effects of entry. It is said that the effect of increased competition will be to push up the overall efficiency and productiveness of British industry. The increased market pressures will force industries to rationalise themselves that at present can afford to work inefficiently because of their monopolistic position in the British market. Labour and capital will then flow to lines of production which are more productive, and, so the theory goes, the national wealth will rise and everyone will be better off.

Again, the CBI has put the argument in its simplest form:

‘... The opportunities offered by, and the stimulus of, free access to a fast and growing market should provide the necessary conditions for achievement by the UK of a significantly faster rate of growth than has been realised in the last 15 years ...’ [17]

Two points need to be made about this argument. Firstly, the rationalisation of industry that is spoken of so glibly will be at the expense of working class people. Whether or not it has a dynamic effect in producing economic growth, the ‘shakeout’ of labour from ‘inefficient’ industries means a dislocation of the lives of many workers. They will lose their jobs – and at a time when unemployment is rising to an ever higher plateau.

Secondly, it is not even evident that this argument is correct from a capitalist point of view. There is no space to go into the technical arguments here, but there is little evidence to back up the facile optimism of the CBI that entry to the Market will somehow overcome the long term stagnation and chronic decline of British capitalism.

The highest hard estimate for the increase in British production as a result of these ‘dynamic’ effects has been one per cent [18] (its smallness can be seen by comparing it with the loss of increased production this year of at least four per cent due to unemployment and under-utilisation of plant). Other favourable estimates are much lower.

Indeed, the National Institute Economic Review, in a report favouring entry into the Common Market, has been driven to conclude that

‘It is hard to think that if the dynamic properties of entry were really so great as is sometimes suggested the statistical evidence would be so completely and consistently lacking’. [19]

It adds that

‘... It is hard to see anything ... which suggests that the United Kingdom’s performance would be improved more rapidly inside than outside the Community’. [20]

What seems to be happening is that mass of the not-so-big British firms, perplexed by the inability of successive governments to solve the problem of economic stagnation and declining profit rates, are prepared to support almost any policy that seems to promise a way out. The leaders of big business who operate oa an international scale are presenting the Common Market as such an easy cure, and business generally is prepared to respond. But it is not at all certain that the cure will work.

5. Military-industrial reasons

The four motives we have given so far for the desire to enter the Common Market have been economic. Yet, as we pointed out earlier, the original motivation for the six coming together was essentially political. More recently such a political motive has once again begun to come to the forefront.

Since the war the defence of the European capitalist states against expansion or coercion from the Russian block has depended upon the presence of massive us forces. Because the strategic needs of the us demanded physical forces in Europe, the European governments were able to feel at ease with levels of arms expenditure substantially below that of the US and Russia.

But in the last few years the increasing difficulties of the us economy have led to growing pressures from within the American ruling class for an end to massive military subventions to Europe. Military strategy – and the profits of the key arms producers – depends upon missile weaponry, operating from the oceans or from continental America itself, not upon land based armies. Voices begin to ask, as Senator Mansfield has, ‘why should 250m Europeans depend upon 200m Americans for their defence?’ [21]

The European governments recognise the difficulties that could confront them in the future. The British government uses the word ‘security’ no fewer than seven times on the first page of its white paper arguing for entry into the Common Market. [22] It stresses that:

‘The United States of America have played and are playing a great and generous role in the defence of Europe; but it is a burdensome one and they now feel it is time for Europe to play a larger part in maintaining her own security ...’ [23]

Some time within the next decade some of the 300,000 us troops at present in Europe will be withdrawn. The European powers will be forced to fend for themselves. But none of them can do so alone.

However, they can dream of reverting to superpower status if the process of economic and political integration is completed. Their combined defence expenditure, they argue, is already half that of Russia’s – and the Russian leaders have also to worry about China on their eastern border. [24]

The construction of a single defence effort would also fit in with the needs of the technological sectors of industry. It would provide a common pool of resources able to match that at the disposal of the American firms. The political needs of European capitalism in all its sectors, it is argued, tie in with the economic-needs of its most advanced industries. Or as the Economist puts it:

‘The defence reasons for Britain joining begin to merge into the economic reasons for doing so.’ [25]

1. Bukharin, Imperialism and the World Economy, New York 1966, p.122.

2. H.B. Price, The Marshall Plan and Its Meaning, New York 1955, p.22.

3. Quoted in ibid.

4. Statement of State Department Planning Group, quoted in ibid.

5. Quoted in ibid., p.122, cf. also R Hinshaw, The European Common Market and American Trade, New York 1964.

6. Federation of British Industries, The European Free Trade Area, London 1957, p.v.

7. Figures given by J.H. Dunning in Lloyds Bank Review, July 1970, p.24.

8. Figures given in Moorgate and Wall Street, Autumn 1969.

9. Ibid.

10. Confederation of British Industries, Britain into Europe, London 1970, p.13.

11. Roy Jenkins in House of Commons, February 25, 1970.

12. Economist, May 16, 1970.

13. Financial Times, August 12, 1971.

14. CBI, op.cit., p.15.

15. G. Layton, European Advanced Technology, 1969, p.51.

16. CBI, op. cit., p.9.

17. Ibid., p.2.

18. For the various different estimates that have been made see N. Lundgren in G.R. Denton, ed., Economic Integration in Europe, London 1969, p.48.

19. NIER, 1970, no.4, Another Look at the Common Market, by R.L. Mayer and S. Hayes, p.31. For a similar argument see the essays by N. Lundgren and J. Pindar in G.R. Denton, op. cit.

20. NIER, op. cit., p.43.

21. Cf. Economist, February 14, 1970.

22. The United Kingdom and the Common Market, Cmnd.4715, London 1971.

23. Ibid., p.10.

24. For a sample of such reasoning, see the Economist, Supplement On the Common Market, May 16, 1970.

25. Ibid.

Chris Harman Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 19.2.2008