Andrew Glyn Archive | ETOL Main Page

Andrew Glyn

Tumbling profits – Crumbling industry

(October 1981)

From Militant, No. 574, 23 October 1981, p. 7.

Transcribed by Iain Dalton.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

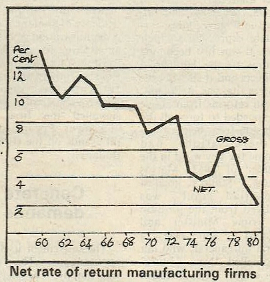

New figures for the rate of profit published by the Department

of Industry (British Business, 18 September 1981, p. 111)

confirm the dire situation faced by the British capitalists.

In 1980 their rate of profit was 4.9%, compared to an average

of 11.6% in the years 1960–65.

But the 1980 figure itself is heavily influenced by the profits

from North Sea Oil. These are of temporary duration. A large part of

them go to the American oil companies, and in any case they have no

bearing on the profitability of the rest of British industry.

Excluding these returns from the North Sea, the rate of industry

and commerce was 3.0%, barely a quarter of the level of the early

sixties. The manufacturing sector, hardest hit by the cuts in

production and the high exchange rate last year, was receiving only

2% on its capital employed.

The situation has deteriorated further this year. Figures are only

available for the first quarter, but they indicate a further fall,

perhaps to 1½% or less for manufacturing. Whilst profitability has

fallen elsewhere, the decline has been sharpest in Britain. Latest

figures (for 1979) show rates of 14% for USA, 10% for France and 14%

for Japan (British Business, 4 September 81).

The Bank of England has just reported that manufacturing

productivity rose by 3% to 4% between the end of 1980 and the middle

of 1981. But as the Bank wryly comments, part of this is probably a

statistical mirage.

If a number of the least productive plants are shut, the average

productivity level automatically rises, without signifying any

genuine gain. Indeed if the workers are thrown on the dole were

counted, their productivity having fallen to zero, the average would

certainly have declined!

While closing loss-making plants does improve profits the only

real improvement in competitiveness occurs through genuine

productivity in the more efficient plants. How much management has

achieved in this respect is an unknown quantity.

The drastic state of profitability has important implications for

the Labour Party’s expansionary Alternative Economic Strategy.

Many supporters of the AES admit that to secure an improvement in

investment the capitalists would require an increase in

profitability. But they often overlook the extent of this increase.

To return the rate of profit of industrial and commercial

companies (excluding North Sea Oil) to the level of the early 1960s

would require an increase in profits of nearly £21,000 million (1979

prices). This represent 25% of what companies are currently

producing. It would therefore take 25% expansion of their output, all

of which would go to profits, to return the profit rate to its

earlier level.

Probably there is spare capacity to increase output by a bit more

than this. Nevertheless, the restoration of profitability would take

the lion’s share of extra production.

Whether or not even this would be sufficient to secure a radical

improvement in investment is dubious enough in the context of

anti-capitalist measures of the AES (nationalisation of profitable

firms, planning agreements, etc.) But there would be huge pressure on

a Labour government to secure such a boost to profits by holding down

on any growth in living standards.

The contradiction of trying to secure production for need in an

economy based on profit would face the government with a stark

choice: Either abandon its objectives or move more decisively against

the profit system.

|

Net rate of return at current replacement price

|

|

|

All Industrial/

commercial

companies

%

|

Industrial &

commercial

companies

exc. North Sea

%

|

Manufacturing

Companies

%

|

|

1960

|

13.3

|

13.3

|

13.3

|

|

1961

|

11.4

|

11.4

|

11.0

|

|

1962

|

10.4

|

10.4

|

9.9

|

|

1963

|

11.4

|

11.4

|

10.6

|

|

1964

|

12.0

|

12.0

|

11.3

|

|

1965

|

11.3

|

11.3

|

10.6

|

|

1966

|

10.0

|

10.0

|

9.2

|

|

1967

|

10.0

|

10.0

|

9.2

|

|

1968

|

10.1

|

10.1

|

9.2

|

|

1969

|

9.8

|

9.9

|

9.1

|

|

1970

|

8.7

|

8.7

|

7.5

|

|

1971

|

8.8

|

8.9

|

7.7

|

|

1972

|

9.3

|

9.3

|

8.1

|

|

1973

|

8.9

|

9.0

|

8.1

|

|

1974

|

5.8

|

6.0

|

4.3

|

|

1975

|

4.9

|

5.2

|

3.9

|

|

1976

|

5.4

|

5.6

|

4.1

|

|

1977

|

7.1

|

6.7

|

5.8

|

|

1978

|

7.2

|

6.7

|

6.0

|

|

1979

|

6.3

|

5.0

|

3.6

|

|

1980

|

4.9

|

3.0

|

2.0

|

|

NOTE: Figures show net rate of return on capital employed. Net

Return means gross operating surplus (i.e. gross trading profits

less stock appreciation plus rent received) less capital

consumption (i.e. depreciation) at current replacement cost. Net

rates of return have fallen more than gross rates. Net rates were

above gross rates in the 1960s, but since 1974 have been well

below them, reflecting the increased share of capital consumption

as profits have fallen. Excluding North Sea activities, capital

consumption has increased from 20% of gross operating surplus in

1960 to 28% in 1979 and 56% in 1980.

|

|

|

Top of page

Andrew Glyn Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 1 November 2016