First Published: n.d., [1975/76?].

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

Unlike many of the world’s capital cities, London is not just a seat of government, an empty urban shell – a mere centre of political institutions. Ever since the mid-seventeenth century (and even before that) it has been the capital city of the British working class. It has been a centre of organisation – the birth place of new ideas – of newspapers and journals – of revolt – of the first trade clubs of skilled journeymen – and later the first national and international trade union bodies. Since the end of the Second World War it has in many ways led the whole trade union movement.

The reasons for this are many and varied – the very long history and development of the city itself – its commercial history – its location on a major river – its port – its sheer size, guaranteeing to its inhabitants safety in numbers and the security of anonymity, which smaller towns and communities have denied to other workers.

Above all, however, it has been the structure of the city’s industry, the great diversity of London’s skills, the size and variety of its working population which has made it the capital of our class. London’s industry has determined London’s political character.

In the early eighteenth century, although tiny in comparison with its present size, London was by far the largest city anywhere in the world. Defoe, writing in the eighteenth century, was obsessed by its size and rapid expansion.

At that time the city was concentrated mainly north of the Thames – it stretched from Tyburn in the west to Stepney in the east. “The whole river, from London Bridge to Blackwall,” wrote Defoe’s editor in 1747, “ ... is one great arsenal: nothing in the world can be like it.”

The city of that time was home to all the traditional skilled tradesmen of the pre-industrial era – printers, coach-makers, building craftsmen, watchmakers, millwrights, instrument makers and so on. Throughout the period of industrial revolution London remained by far the largest concentration of skilled tradesmen anywhere in Britain and consequently the world. This was one of the main reasons for the great diversity of industrial development that occurred in the city’s growth throughout the nineteenth century. The clothing industry throughout London, the furniture industry around St. Paul’s, the printing trades in Fleet Street, the City and Long Acre – precision industries, instrument making, shipbuilding, marine engineering, general engineering, other heavier metal industries and so on.

In the nineteenth century London’s industrial development was concentrated mainly in what is now Inner North London. With the coming of the twentieth century, industry expanded greatly, especially to the north and to the west. At first it was localised, but in the first decade of the century, areas such as Willesden Junction, Acton, Hythe Road and Scrubbs Lane became established as centres of engineering. Typical of this development was the establishment by Napiers in 1902 of a car factory at Acton Vale. By 1904 it employed over 500 people.

The First World War witnessed the development of Park Royal as the centre of the munitions industry and in the post war period this site became the heart of an industrial expansion which occurred throughout the London suburbs in the twenties and late thirties, and during the whole period of the Second World War. Known as ’Red Park Royal’, it became eventually the greatest concentration of engineering establishments anywhere in Europe. It gave rise to a roll call of famous industrial names – now all gone.

By the beginning of the fifties Greater London was still by any yardstick Britain’s first manufacturing region. The 1951 census showed 20.2 per cent of all workers employed in Britain’s manufacturing industry worked in Greater London. Many important industries were highly concentrated in London. 54. 9 per cent of persons employed in the manufacture of office machinery worked in London; 55 per cent of the electric lamp and valve industry; 53 per cent of optical instrument manufacture; 57.6 per cent of the manufacture of measuring instruments: the list is endless.

Precisely because London has been the industrial hub of Britain, so it has also been the political and organisational heart of our class.

London has witnessed most of the major developments in the history of the British working class: the corresponding societies of the eighteenth century; the repeal of the Combination Acts 1824; the London Working Men’s Association 1836; the 1850s and the foundation of the Amalgamated Societies of skilled tradesmen; the Junta; the International Working Men’s Association 1864; Marx’s first publication of ’Capital’ in 1867.

For over two hundred years London has been one of the leading cities of struggle in Britain. As early as 1721, before the repeal of the Combination Acts, it was the master tailors of London who were amongst those who petitioned Parliament against their own journeymen. Numbering over seven thousand, it was claimed that they “ . . . lately entered into a combination to raise their wages and leave off working an hour sooner than they had used to do; and for better carrying on their designs have subscribed their respective names in books, prepared for the purpose, at the several houses of call or resort ... where they used, and collect several considerable sums of money to defend any prosecutions brought against them.”

Throughout the twentieth century as the city became a vast industrial metropolis, London developed a higher density of trade union organisations than many other parts of the country. For instance, during the fifties Acton alone contained over half the entire AEU membership in London.

Wages in London have always been higher than in the provinces. As early as 1813 the skilled craftsmen of London received 36s 6d per week: his counterpart in Manchester only 25s per week, and his brother in Glasgow only 18s. If wages have been higher, however, exploitation has been greater too, the average output per person employed in many of London’s industries being greater than that in other parts of the country.

From almost all points of view London’s workers have led the working class of Britain. In particular, London engineers have often led the way for others – for example in achieving shorter working hours and paid holidays. It was London’s engineers who first raised the now widely accepted demand for the right to work, challenging for the first time the right of the employer to sack.

Since London has been such a centre of struggle, it was no historical accident that in 1968 it witnessed the creation by workers, many of them Londoners, of the first revolutionary party of the British working class, the Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist).

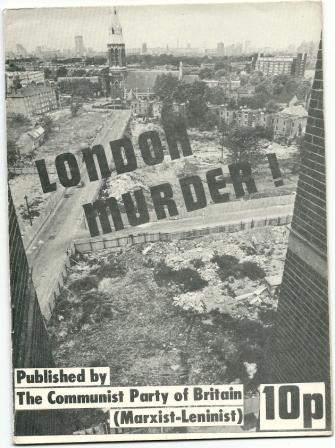

The industrial decay of London has accelerated rapidly since 1966 and the structure of employment in the city has undergone a more rapid alteration than at any other time in its recent history. Some of the reasons for this change can be traced to the anarchic and unplanned way in which big cities grew up and are now decaying under capitalism. More ominously, however, all evidence points to what seems to be a general and deliberate policy aimed at exterminating the city’s industry and consequently the working class.

In addition the economic advantages of locating industry outside London in the smaller and medium sized towns have a lot to do with such things as reduced transport costs, lower rates, and, above all, leaving behind a highly organised workforce, employing fewer people elsewhere and paying lower wages.

The whole trend in the organisation of firms, now more than ever before, is one of concentration of production into larger enterprises through take-overs and mergers. By 1980, it has been calculated, the top 100 companies will control 65 per cent of national production. Small firms are either being closed down, taken over or are not growing at as fast a rate as large firms. This process has been e1’lcouraged by Britain’s declining world capitalist position. More importantly though, it has been actively promoted by successive government policies aimed at ’rationalisation’, to make British monopolies competitive with their foreign counterparts. (This was the role, for instance, of Labour’s Industrial Re-organisation Corporation.)

Part of this so called ’rationalisation’ process involves replacing expensive labour and land (particularly in London where industry competes with housing and office space) with more machinery, cheaper labour, and cheaper and more plentiful land elsewhere – hence the move to cheaper areas away from city centres.

A whole climate of opinion has deliberately been created, by government and private propaganda, in the mind of city-based management to further promote industrial emigration from large centres, particularly London. (Take, for example, the role of the Location of Offices Bureau, L.O.B.)

In the words of one planner, “... moving out has become the natural reaction of the rational manager, and staying put the hallmark of a reactionary or lunatic.”

Both national and local government have consistently attempted to present the run-down of industry in London as both natural and desirable. From ’The strategy for the South East’ in 1966 to present policies, the false image of work and security in other parts of the country has been contrasted with unemployment, overcrowding, and the so-called ’environmental’ problems of the big city.

Throughout the sixties, for example, as the capital experienced a rate of industrial closure unparalleled in its history, the image of ’swinging London’ was promoted to turn the city into a ’candy floss’ economy for the benefit of foreign tourists.

The movement of industry out of the city has been fuelled by government policy just at a time when the de-industrialisation of London was gathering pace for other reasons: urban areas have been allowed to become congested , road networks blocked, rail services cut and dock transport closed or containerised. Some of the measures designed to accelerate this movement further include ’grants’ to firms to move to development areas, selective employment tax and redundancy payment schemes which enabled firms to jettison workers more easily. Industrial development in London itself is now being further curtailed by firms having to apply for a special Industrial Development Certificate from the Department of Trade and Industry if they wish to expand their factory space by more than 10,000 square feet. (Recent government moves have attempted to halve this figure.)

The most rapid contraction in employment in London has been amongst men working in manufacturing industry. From 1961 to 1971, for instance, male skilled workers in London declined by about a quarter (743, 480 in 1961 to 561,730 in 1971). All ’blue collar’ employment in London declined by, a third of a million men. ’White collar’ workers are now in a majority in the city.

The loss of jobs has been gathering pace. A survey of redundancy between 1966 and 1972 , involving firms making more than twenty workers redundant at any one time, showed that these had shed 217,400 from the labour force in that time. Most of these redundancies were in the manufacturing sector – 37 per cent of all male redundant workers were in the metal and electrical industries ’alone, and 32 per cent in the rest of the manufacturing sector, excluding textile and footwear industries (where 7.8 per cent of the losses in this period occurred).

The degree of redundancy in the manufacturing sector overall has been considerable, with 75 per cent of all male redundancies concentrated there, By contrast, during the sixties a mere 4 per cent came from the construction industries and only 20 per cent from service industries, although together these latter sectors accounted for over 70 per cent of London’s workforce in 1966.

The inescapable conclusion is that a major contraction has occurred throughout all areas of manufacturing industry in London during the sixties.

Although less than a third of London workers are involved in manufacturing industry (in 1966 29 per cent of working men and 27 per cent of working women), de-industrialisation affects the whole structure of employment and hence the whole city.

Some areas have been affected more than others. The Inner London area has suffered most. This was traditionally the Victorian manufacturing belt – it was the single greatest cluster of individual factories in London. Made up of old, small, often multi-storeyed buildings, it forms a wide crescent along the northern edges of London’s central business district.

Other areas affected include the Thameside industrial belt, the Lea Valley and Tottenham, and the industrial concentrations farther out along rail and road routes into London. These include Cricklewood, Perivale, Wembley, Isleworth and Hayes. In the north west dominating them all is Park Royal which, although it has been decimated, still employs over a quarter of London’s industrial work force.

Research by the GLC has shown that the loss of jobs in London has been due overwhelmingly to:

1. complete. closure of plant or unit

2. transfer of production to other centres

3. compulsory purchase orders

4. re-organisation of production methods

5. economic difficulties and failures

6. take-overs and mergers.

The same survey in looking at all firms implementing redundancies in the Inner London zone from 1971 to 1973 found that in South London, out of 80 firms involved, 41 were closing altogether, 15 were transferring production to other centres out of London, and 3 were subject to compulsory purchase order. In North London, out of 90 firms involved, 31 were closing down altogether, 25 were transferring production out, and 2 were subject to compulsory purchase.

Since there has been a conspiracy of silence over the extent of closure and redundancy, these figures can only hint at the true scale of changes that have occurred. These in turn, however, represent only a part of the wider panorama of industrial destruction and decay throughout Britain which has been caused by speculation, profiteering and the export of capital – particularly now to EEC countries.

As the de-industrialisation of London has gathered pace, so has the decay of life in London. There has been a change in the make-up of the population in many-areas. Skilled industrial workers seem to be having to leave London altogether or take work which is available but which does not involve their particular skills. Unemployment, however, is highest amongst the less skilled. Building labourers and routine clerks are now, for instance, two of the biggest groups amongst registered unemployed in London.

The implications of these trends were even recognised by the Greater London Development Plan which argued, “ ... falling population with accelerating decline in manufacturing employment will deprive London of young, skilled, well-educated people". It concluded that the city will become home to the old, the less skilled, the poorer sections of the community and what are euphemistically called, ’the socially disadvantaged’. The middle mass of industrial workers and their families will be lost and only the extremes of very poor and very rich will remain. Inner London, in particular, has already become the rotten centre of a dying city – the focus of crisis in health, housing, education, social services, etc.

It is this middle mass of workers, however, who have to provide much of the city’s rates and revenues. Industry, as a major rate payer, is going elsewhere.

At the same time, the government deliberately discriminates against London in the aid which it gives to the city’s finances. To camouflage this the idea is put about that London (i.e. the City, etc.) is rich. What is not mentioned is that this wealth is now concentrated in over-inflated property values and not rateable values, and hence is not taxable. By applying bogus formulae based on this disparity, the government cheated London out of £156 million of rate support finance in 1974-5. The increased rate burden has to be borne by the domestic ratepayer. Hence rate payments are approximately 29 per cent higher in London than elsewhere, while the government grants account for only 38 per cent* of London’s rate fund expenditure, compared with 55 per cent elsewhere in Britain.

As the exodus continues, London is trapped. The old and very poor who remain behind consume proportionately more but contribute proportionately less to the city’s finances. London has now 100,000 unemployed men (more than 10 percent of all unemployed in Britain). The income of the poorest 25 per cent[1] of London households dropped by 12 per cent (1965-73), while in the rest of the country it rose by 12 per cent in the same period.

The quality and quantity of every public service are deliberately reduced precisely at a time when an increasing proportion of London’s population has greater need of them.

Thus the policy of destroying London as capital of the working class extends not only to the closure of industry – depriving London people of work – but to an attack on every public service – depriving Londoners of security and dignity. This is well illustrated if we look at three areas of vital importance to all London workers and their families: housing, education and health.

London is destined to become not just an industrial wasteland, but one of the slum centres of Europe. The GLC estimate that thousands more older houses will be nearing the end of their useful life in the 1980’s than in the 1960’s. About two-fifths of the housing stock (about one million dwellings) were built before 1914. A quarter of all Londoners live in unsatisfactory housing conditions. The number of homeless families has doubled between 1966 and 1972.

The fact that the population of the capital has been declining since before the war has done little to ease the situation. Each dwelling should accommodate one household, but because of the rapid increase in small households, the total number of households has been increasing. It is no accident that 38 out of the 39 GLC designated ’worst housing stress areas’ are concentrated in the Inner and Central London zones.

What is the response to these problems? The rate at which new housing is being built is now the lowest for twenty years. This is reflected in the fact that manufacturers of building materials are facing acute problems of over-production. Large-scale redundancies in the building industry are accompanied by massive stockpiling of bricks. Government and local councils are cutting back on housing expenditure.

The money allocated by the government for improvement of London’s older houses has been slashed ... it is less than 70 per cent of what the councils requested, and they have been told not to enforce’ . . . unreasonably high standards’ in new building and in conversions. At the same time the government has instructed councils to make ’substantial’ increases in rents and the price of services. It has even been recommended that tenants take in lodgers and that ’multiple occupation’ (several households sharing one house) would help solve London’s housing problems!

As the size of London’s housing problems grows so do acres of unused office space. Open scandals such as the Centre Point offices represent but the tip of an iceberg. There is no part of Greater London in which the laying waste of whole areas, the destruction of communities and families has not been carried on in the name of ’development’. The plans for the ’new’ Covent Garden, for instance, illustrate so clearly the callous and rapacious collusion of planners, bankers, speculators and building consortia that has turned the London landscape into a pale imitation of the American city – brash, ugly and chaotic.

London children have always suffered from cramped conditions at home, at school, at play. At school many children attend classes in corridors or cloakrooms. School halls serve as dining room, gymnasium, assembly room, classroom. Some children have to cross a playground to go to the lavatory.

Books, paper and equipment become scarcer and dearer every term. The Inner London Education Authority has adopted a policy of ’nil growth’, which really means drastic cuts.

Nursery classes are being axed. The future of some whole schools is in jeopardy. Colleges of Education are being closed, shrunk or merged. Fewer people are trained as teachers. Up to one third of the newly qualified teachers emerging from London colleges in July 1975 faced immediate unemployment. Two fifths of all school leavers in July 1975 were destined to be still unemployed by the autumn; London youth takes its share of this shameful waste.

The worst aspect of the attack on education in London, as throughout the country, has been the decision to cut down on the most important factor – the teachers. In September 1974, 1300 teachers were newly recruited to London primary schools. In 1975 only 698 were recruited and the actual number of primary schoolteachers employed in London dropped by 300.

Half this decrease was due to an estimated fall in the number of primary school age children, partly caused by the slashing of industry in London. Half was due to education cuts. Either way the politics are the same. The attack on our class comes from many different angles: the filching of education from children and the filching of jobs from their parents are two parts of one strategy.

The beginning of the struggle to save education in London came with the teachers’ struggle for the London Allowance. London teachers combined their struggle for a decent London Allowance with the struggle for a decent education. By refusing to cover for absences or vacancies they showed up the shortage of teachers, particularly in certain specialisms. In many cases this necessitated part-time education. By simply allowing part-time education the authority was in breach of the law and the whole affair demonstrated the authority’s utter contempt for children and education.

Two London boroughs deserve special mention: Barking and Newham vie for the lowest educational standard in the country. Fine harvest did Newham children reap from their MP erstwhile Minister for Education, Reg Prentice!

The fight to save education in the capital which so far has fallen on the shoulders of London teachers must now be supported and pursued by all who live and work in the city – and then not just by parents of school children. If now the destruction of London proceeds in the first instance via the closure and dispersal of industry, it will be ensured in the future by denying to a new generation of London workers literacy, numeracy and the basic educational attainments upon which industrial skills are based.

This point has been dramatically borne out by the rapid decline in the number of new apprenticeships started every year in London since the beginning of the sixties.

Problems of health in Inner London are greater than anywhere else. There is a higher proportion of people with mental and physical handicaps than in the whole population. The poorest areas economically are also the poorest in health.

Cuts in expenditure on the health and social services, begun by the Tories, are being increased by the present Labour Government. Funds for the building of health centres have been withdrawn –General Practitioners continue to work from shabby, run-down, premises in the declining areas of the city. Amongst hospitals, the worst affected are the long stay psychiatric and geriatric. Because the social services are increasingly unable to support them at home, the elderly and infirm are finding last refuge in the casualty departments. Many beds in acute wards are so ’blocked’ – what a way to talk about people – until death, or after months of waiting, transfer to a psychogeriatric ward settles the issue.

Some small specialist hospitals have been closed. Others await the axe. This results in a small saving of pounds, and a large loss of training centres of high quality. ’Thinking time’ is now too expensive.

The NHS employs mainly women. It does less than any private capitalist to allow for the needs of women. Certainly, there will be no money for the creche, the part-timer, the re-training scheme.

The NHS will continue to function. It will, like the curate’s egg, be good in parts. It will become more inefficient. It will become less humane.

Why has the response to what has happened to London been so muted? Perhaps because a city under capitalism is such a vast, complex and chaotic organism, that its inhabitants fail to recognise how vital their individual industries and firms are to its future.

Perhaps because during the fifties emigration from London and the creation of the new towns provided the illusion of work and security in the countryside.

Perhaps because important fights such as the ’Napiers closure’, in which workers said their factory would not close, gave way later to acceptance of government financed redundancy payment schemes, designed to thwart such struggles in future. Perhaps it has been the idea, particularly prevalent during the sixties, that there has always been another job within easy reach, which has too often provided Londoners with the excuse not to confront the destruction of their city head-on. Taking the line of least resistance – attempting to adapt to industrial decay instead of challenging it, has exacerbated the present situation. It was short-sighted. Once lost the jobs were gone forever. Witness the annihilation of the aircraft industry in London (and throughout Britain), Napiers, Handley Page, De Havillands, Fairey’s , to name but a few major manufacturers – all gone.

Since the end of the sixties, the rising rate of redundancy in London and the complete absence of new manufacturing industry have combined to make it much harder for workers to sustain the illusion that ’there is another job down the road’.

It was against this background that the seven week occupation of Crosfield Electronics, Holloway Road, earlier this year, marked a new ’high’ in the struggle for the right to work – the right to work in London and not to be forced either to other towns or now abroad to EEC countries.

It was principally because the majority of workers involved had previously experienced similar redundancy – some three, four or even five times, that they had no illusions about the situation that faced them.

Crosfield Electronics, a smaller private company, was bought in 1974 by the De La Rue Group – a big multi-national company.

What happened to Crosfields illustrates vividly the fate of many smaller firms which are subjected to ’rationalisation’ when-they are incorporated into bigger companies by such take-overs and mergers.

Crosfields produced photo-scanning equipment for the print and newspaper industry. It was an exporter. Its product was a world leader, incorporating advanced technology, unique design and superior craftsmanship. De La Rue decided to run down and close Holloway Road and transfer production to Peterborough.

Why? Was it because of economic difficulties? Was it because of lack of orders? Was it because of ’cash flow’ problems? Had Crosfields been a bad acquisition for De La Rue? Or was it because Crosfields had, over a period of time, become a highly organised factory?

The workers’ answer was clear. The fitting-shop building which was to be closed was occupied on the day prior to the expiry of notices warning of the closure. Workers from other parts of the factory assisted in barricading the building: assisted in picketing it for seven weeks, and raised a weekly levy to supply food to those in occupation.

The high degree of organisation, conviction and ingenuity necessary to carry out such an operation proved conclusively that workers have both the confidence and ability to run any operation they choose. They do not require an army of management to supervise them.

The dispute was well supported by fellow trade unionists. Lorry drivers refused to cross picket lines. Electricians refused to disconnect the electricity supply.

On the other hand, although those who led the Crosfields struggle understood that success or failure depended on their own determination and that of fellow trade unionists, some workers still hoped that someone in power could help them. When deputations to MP’s, ministers and councillors proved that these merely passed the buck from one to the other, the lesson was learned that Crosfields workers would have to rely primarily on their own efforts and those of fellow trade unionists if they were to defeat the employer and save their jobs in London.

It was a revolutionary fight. The use of the police force to escort finished products out of the factory in the middle of the night – the use of tortuous legal processes, after ten weeks of dispute, to serve writs on those in occupation – the use of bailiffs, police, twenty-ton trucks and all the apparatus at the employer’s disposal – the denial of social security benefit to workers’ families – all this showed how the whole panoply of the state is arrayed in assisting the employer against those who would defy capitalism. And for what? Simply the right to work in your own town.

In finality, because of the strength of the forces employed against them, and because of insufficient time to rally support from wider sections of the trade union movement, Crosfields workers were faced with the agonising decision of whether to stage a tactical withdrawal or face a complete rout.

Although they chose the former course, their actions had not been a defeat. Not only did they withdraw in dignity, keeping their organisation intact, forcing concessions from the employer after costing him an immeasurable amount of money, but they had raised the banner for the whole trade union movement in London – to now challenge every closure, every redundancy and every transfer of production.

Why has London been run down? Who is responsible? Planners say no one is. They tell us the causes are economic, part of an inexorable process of so-called ’urban decay’. Employers, in closing their factories, say they cannot make ends meet in London. Is any of this true? Of course not!

Capitalists move away from London simply to escape from the organised working class. London is not dying of old age – it is being murdered. This is part of the political strategy of the ruling class. It flows directly from their desire to destroy everything which we have attained hitherto – employment, trade unions, education, health and standards of living.

A senile and decadent capitalism cannot afford a dignified, healthy and independently-minded working class, especially at the heart of the nation. It aims to pauperise – to reduce ail to obedience, servility and ignorance – to turn industries into empty shells – people into automatons and cities into deserts. What capitalism has achieved in London, capital of the working class; offers but a glimpse of what the bourgeoisie has in store for the whole of Britain. This is what a counter revolution means.

Since London is the heart of our class, this attack is concentrated here.

London must stand up now and shout NO!

– NO more industry shall leave London

– NO more jobs shall be lost

– NO more cuts – in housing – in health – in education – in transport – in social services.

The time has long passed in which to stay silent. The voices which have already been raised, by Crosfield’s workers, by teachers, by health workers, by civil servants, and by many more, must be joined by all to become a great crescendo of revolt and revolution.

It is not London that shall be murdered, but capitalism!

Save London – smash capitalism!

[1] All statistics are from F. T. Hollocks, Chairman Greater London Council Staff Association – The Times (5.9.75)