First Published: n.d. [1978/79?].

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

Capitalism is in absolute decline and devolution is one of British capitalism’s ways of trying to counter this – by attempting to dominate and crush the British working class by division. They are impelled by fear of our class to destroy Britain and the British working class. Their attack on us, on our trades unions, industry, health service, education, housing, skills and living standards is on the one hand an attempt to tame us and, on the other, signals capitalism’s abandonment of Britain in search of greener and more profitable pastures abroad. Capitalism both seeks to make us more docile by destroying us, and flees with the wealth we have created.

Britain’s entry into the Common Market is part of capitalism’s strategy of survival – entry into an economic cartel, a club of now second-rate but still powerful and dangerous capitalists who seek to regain lost empires and past imperial ’glories’: a club to ease the movement of capital and investment across national boundaries and to help out individual national capitalists in times of ’trouble’ with their working class. The Common Market, with its goal of political unity, is meant to eliminate nationhood, amalgamate cultures and traditions and do away with the individuality of the British people and of other peoples of western Europe. The pure opportunism of the call for devolution can be seen clearly by the fact that those who shout the loudest for it, supposedly in the name of preserving national cultures, are also those who were and still are in favour of the Common Market.

The goal of a world in which the working class organises and controls its own destiny can only be achieved through the combined development of socialism in individual nations. Socialism cannot be imposed from outside – it can only be made by, and for, the working class where it lives and works. Hence the importance of a proper understanding of nationhood and hence also the dangers of an improper understanding.

Nationhood is the essential genius of a historically constituted community which, in a particular geographical area over a considerable period of time, has developed as a single economic unit with its own peculiar arts, culture, skills and language for the enrichment of life. The fact that there are differences throughout Britain in culture and sometimes language (but usually only accent) does not make those individual localities into separate nations. Likewise, neither do the similar cultures and language of the Americans and British make them into one nation. This pamphlet shows that the development of England, Scotland and Wales into a single British nation was a logical historical process, although, as with the transformation of any society from being predominantly feudal and agricultural into being predominantly capitalist and industrial, this process was often brutal.

In contrast, the history of Ireland consists of 800 years of invasion and domination. The history of Ireland is a history of the fight for freedom from British (not English) capitalism, colonialism and imperialism. From the 15th Century to today, the people of Ireland have rebelled against the rule of Britain and the division of Ireland into north and south in 1920 makes the struggle there one of national liberation from colonialism and for the unification of Ireland.

Devolution for Scotland and Wales, which must be seen as the first step towards the internal breakup of Britain, has nothing to do with liberation and no section of the working class will benefit. The argument that the Scottish people will benefit more from North Sea Oil after devolution or independence is a fallacy. None of our natural resources will be put to a sensible or beneficial use until the working class itself has gained state power and is able to control the use of these valuable and irreplaceable resources. Otherwise, they will be frittered away for some short-term profit, sold to the highest bidder. It is as if the workers in London benefit by having the world’s financial centre on their doorstep, or the workers in Yorkshire will become wealthy because of the large coal deposits there. It is the question of who owns and controls these resources which matters: otherwise the argument becomes one of whether we want our exploiters to have an English, Welsh or Scottish accent, as if that mattered.

The following sections point out clearly that what does matter is the need to preserve the long history of British working class unity in the face of attempts to divide and destroy.

Nationhood in Scotland was virtually entirely a creation of the feudal period and died with the closing of that period. Even before the union of 1603, capitalist forces were present to a significant extent in Scotland (in contrast to Ireland). Feudalism had been extremely weak, and like the other weak links in feudalism (The Low Countries, Bohemia, Switzerland) where capitalist organisation also become established at an early date, Lowland Scotland found the rapid spread of capitalist development a familiar, although quite brutally introduced, event, certainly not a development imposed from without.

The futile attempts at restoration by the Jacobite Royalists were always shunned by the new, emerging proletariat of the Lowlands (although the struggle of the peasantry of the Highlands against the murderous encroachment of the new capitalism were just as praiseworthy as the exploits of the Luddites). In the 1745 Rebellion the industrial west of Scotland was as keen to keep the Highland Army away and did so mainly by bribery, as it was keen to attract English capital at the beginning of the century. The brutality of the Clearances and the massacre of Glencoe, all part of capitalism establishing its dominion over feudalism, were perpetrated by Scot on their fellow Scots.

For over 200 years the working class tradition has been to look and act beyond the bounds of its own locality. For example, Scottish workers took a leading role in the founding of a union in the Cotton Industry for the whole of Britain (in the 1830’s) and in the Coal Industry (in the 1840’s) , and the sense of belonging to national unions was expressed through the Grand National Union of Spinners, the Grand Consolidated Trade Union, the first Trade Union delegate conference to be called, which was held by Glasgow Trades Council in 1864, and the uniting of the unions in the British Trades Union Congress in 1868. The same outward-looking attitude was extended to the political field, from the reform movement of the early 19th Century and the solidarity demonstrations after the Peterloo Massacre to the Chartist movement and the consolidation of the Labour Movement at the end of the century. The lesson that to survive in the harsh conditions of the Industrial Revolution, a unity with class brothers throughout the island must be forged was particularly learned locally in the essential class unity between the Lowland Scots, the immigrant Irishmen and the Highlanders who flocked to the cities and were virtual immigrants. All this applies especially to the industrial centre of the West and Central Scotland.

From the very beginning of the emergence of capitalism, there was division between highlands and the smaller, commercialised lowlands. This resulted in Scottish capitalism being dependent on outside support from its very beginning. So we find these anti-feudal elements allying with their English equivalents in the so called ’Hough Wooing’ of 1543-50, the union of the crowns, the anti-absolutist alliance after 1638, and the intervention of the covenanters in the English Civil War, out of realisation that their survival was bound up with its result. A short period of almost equal integrated partnership between the two ruling classes, perhaps the best example of which being the use of Scots settlers and capital in Ulster, followed the 1603 union of the crowns: but it was the 1707 parliamentary union that was the logical outcome of national capitalist development, recognising the broader need of the ever-growing capitalist state while being of advantage to the capitalist interests involved. Both sides needed it, both sides used bribery. And it was the most vigorous of these developing capitalist forces that pushed the merger through, not the craft and traditional areas of capital, it was particularly-the big landowners and West Coast merchants of Scotland whose close identity of interest with their southern counterparts was clear. To neutralise the French base in Scotland (a traditional alliance) as well as the Scots’ desire to share in the boom of the Empire and in the ’New World’ after their abortive attempt at exclusively Scottish colonialism in Darien, were important elements.

The feudal counter-revolution, so successful at restoration in the rest of Europe, had found its base in the highlands and had adherents throughout Britain. It formed a threat to the onward march of the new and all – embracing capitalism. The union was thus very expedient, definitely not a colonial relationship, a political union quite distinct from the colonial relationship with Ireland or with the American or Asian Colonies. It was the willing integration of one set of capitalists with another for mutual advantage. Glasgow rapidly became the centre of the American tobacco trade: half the tobacco imports into Britain came to Glasgow by 1775. The west coast became the main coal supplier to Ireland. In the farms of the east, innovations were pioneered, the fishing and linen industries were boosted, wool from the borders was sold on the Yorkshire market. Factories expanded quickly in the late 18th Century into iron and into cotton manufacture too, especially when the Glasgow Chamber of Commerce began pioneering the concept of all-British cotton manufacture. And, of course, there was Adam Smith, Scottish, but a high priest of a national capitalism. There may be a grain of truth in this quote from a certain Tory gentleman about the Scottish bourgeoisie (which word he equates with ’good’):

For 360 years the good Scot has been a good Briton. For long before that he was a better European than was the Englishman and he has certainly been a good imperialist and internationalist. The British Empire could be even more accurately described as Scottish.

As for partnership in Empire-building, think of the names: Macpherson and Dalhousie in India: Macdonald in Canada; Mungo Park and Livingstone in Africa and Jardine-Mathieson in Asia.

So much for the bourgeoisie and the industrialised lowlands; meanwhile the population of the highlands was brutally dispersed by capitalism, its people either emigrating, swelling the ranks of the lowland proletariat, or becoming victims of the rack-rents of the crofts.

During the 19th Century certain figures are revealing and in complete contrast to Ireland. Scotland was only slightly behind England in such items as incomes per head, size of industrial populations, letters post, and so on; and up to 1914 the West of Scotland had a lower unemployment rate and was more industrialised than many urban areas of England.

Any disadvantages, and there is a long catalogue, are to be put fairly and squarely at the door of capitalism, not any national oppression, but the features of capitalism: its quite unsentimental, profit-first motives, its uneven development, its cynical disregard of peripheral areas of its land. Raw materials flowed where capital dictated, everything was subordinated to the City of London, the great heavy industries gradually fell, slum housing was widespread, public health was abysmal and after 1914 unemployment soared. Between the Wars, industry in Scotland did not recover and had no strength to cope with the monopoly capitalist developments following 1945, where there had been a spectacular invasion of foreign capital, and by 1969 the amount of US investment per head was second only to that in Canada and double that found in the rest of Britain.

So that is a general summary of the creation of an integrated capitalism throughout Britain and its natural creation, a proletariat, its leading sections always looked to the forging of national links among its ranks, in response to constant attack by all-British capitalism. The necessity for such unity is ever greater today, with the ferocity of capitalism in decline increasing and its centres of power not necessarily even residing within the borders of the country.

All this is not to say that there are not several distinctive cultural traditions in Scotland, which, by the way, only socialism could save and bring into full play. The process was of a bourgeois revolution absorbing the entire society into the new state, the first in the world to complete the process.

Although capitalism has integrated the parts of Britain into a complex whole, we cannot ignore the uneven and uncontrolled development, and now decline, of capitalism. It is this that the nationalists and others, denying the class nature of the development, distort and portray as ’national oppression’.

There was the failure to stern the decline in heavy industry after the First World War, again after the Second; and today the dismantling of industry is seen nowhere as clearly as in the West of Scotland. The social and industrial problems here are as bad as any in Europe and the current loss of steel alone will leave the West of Scotland emasculated beyond all recognition. Redundancy in fact applies equally to sectors where growth should be most expected, including electronics and power. In the Sixties there was a transformation to a service economy, into the fields of cars, insurance, banking, administration and tourism.

Even oil is proving difficult for capitalism: oil, which socialism could use as a rich asset for the people, is being eaten into by alien monopolies, an ever growing overseas debt and deficits in the balance of payments. And this is coupled with the failure to create oil-related industries and the lost chance of using native steel, design and plant in this field. The number of jobs created by oil is to be measured in the tens of thousands (only 30,000 by 1975) and is far exceeded by the annual loss in the rest of manufacturing industry. Another feature is the shift of capitalist investment away from the socially useful but less profitable manufacture, to oil production. An American financial journal was quoted a couple of years ago as saying that the oil multinationals are “standing in the forefront of the fight against socialism in Britain”. It would seem they have quite an interest in the dismemberment of Britain, and have quite a willing tool in the form of the Scottish National Party. So we have a picture in which the uneven development of capitalism has created a peripheral area where now there is renewed interest on the part of capitalism. And the attempted neutralising of Britain’s sovereignty by the EEC has left it, Scotland, and her natural resources, easy prey for multinational capitalism. The disintegration of national political integrity by the centralisation of the Common Market goes hand in hand with the economic annexation by the multinationals which have no respect for any national border or national integrity. The EEC is capable of claiming allegiance and direct contact with an area or peripheral region over and above the head of the country in question. In keeping with this the SNP are not against the EEC but demand separate representation at Brussels. As we know, the EEC is a manifestation of international capital, so there should be no surprise at a sort of hiving off of peripheral regions to interested parties, especially given total co-operation by the resident capitalist interest. ’Multinational’ capital is now the overwhelmingly dominant form and it has the ability to extract capital and production from the less profitable area to the profitable one, thus also possessing the ability to destroy and threaten a weak, declining national economy. Moreover the Common Market gives British capital its big chance to go wandering abroad in search of happier returns on investment, usually a weak section of the European working class. The small capitalist force residing in Scotland is under the illusion that it is free to conduct a similar exercise. In fact it is almost totally dependent on the multinationals. As capitalism declines, the role of the se client capitalists will become, as is becoming, one of ever in creasing antagonism towards our working class. After all, only a desert economy is required for the extraction of oil!

There is a race against time to save Scotland and the rest of Britain from capitalism, a race against destruction. There are others who also regard it as a race against time. The quote is from the then new US consul to Scotland, who had recent experience of work in Vietnam, Moscow, the Common Market and had been Kissinger’s oil adviser. He said: “It is time the Scots realised the heavy responsibility upon them. There is much more involved than Scotland. Not only is the future of Scotland heavily connected to the successful development of North Sea Oil, but the future of Western industrial life. If produced now, it could help ward off economic disaster. It is a race against time”. He continued, “Scotland is where the action is. Those who will do the work are here, or are arriving. Those who will make the decisions are here or have their representatives on hand. It is towards Scotland that the forces that will determine the outcome are converging. The stakes are high and the responsibility heavy”.

In the face of this type of attack, the capitalists in Scotland and their political reflection, the SNP, let alone the role of social democracy and its desperate opportunist manoeuvrings, advocate industrial harmony and an end to ’class war’, attack ’London mismanagement’ and promise ’wealth beyond our wildest dreams’. For whom, exactly, it must be asked.

Meanwhile the biggest dislocation since the Industrial Revolution is occurring in Scotland. The decline of Britain reveals itself suddenly now in the redundancies in the whole field of technology as well as the run down of traditional industries. The west and central industrial area of Scotland languishes while labour migrates east often for short lived booms in employment there. But these types of problems, of capitalism, once chronic to Scotland are now so for the whole land.

Scottish industrialists are aware of the potential of devolution and the SNP as a means to divide the working class. (Witness Sir Hugh Fraser and the nearly 200 businessmen he recommended for membership). The Scottish Council (Development and Industry) is a devolution supporter and its Research Institute is noted for its support for a Scottish Parliament which it sees as having a key role to play in the improvement of Scotland’s ’shocking’ record of industrial relations and its role in assuring a stable labour market. There is thus the desire present artificially to create a new Scottish ruling class embellished with the usual trappings of bourgeois democracy.

The attempted diversions from the struggles that are of real and vital importance for the whole working class are encompassed in written form in the ’Kilbrandon Report’. Its major concern was that a measure of faith in democracy and other capitalist institutions be restored. Very significantly this (and, by the way the growth of the SNP) came hot on the heels of the years that, contained the new waves of occupations , the UCS struggle, the massive national demonstration in Glasgow and London, the political strikes, abstentions and growing anti-parliament attitudes.

The Kilbrandon Report was well aware or this development of the consciousness and the role of the working class. It pinpointed “a diffuse feeling of dissatisfaction ... a feeling of powerlessness at the we/they relationship”. On the growing antagonism of workers against the growing corporatism of the system, they admitted their awareness that the “vast increase in scope, scale and complexity of government business, and in manpower and other resources devoted to it, has had a cumulative effect on people’s lives and is an underlying factor in complaints about the working of the present system ... ” And about workers’ attitudes to the system itself:

“They have less attachment to it than in the past, and there are some substantial and persistent causes of discontent, which may contain the seeds of more serious dissatisfaction.” Then it adds: “Devolution could do much to reduce discontent with the system of government. It would counter over-centralisation, and, to a lesser extent, strengthen democracy: in Scotland and Wales it would be a response to national feeling”.

On top of all this has been the recent form of ’devolution’ already enacted, the imposition of a new local authority structure, more corporate, more bureaucratic than before, more efficient in cutting back on industry, health and education.

The whole tone of the nationalist, Plaid Cymru, propaganda is devoted to showing that Wales is a victim of English imperialism, and that the solution to Wales’s ills, economic, social and cultural, is an independent Wales with its own parliament.

It states that Wales’s culture and institutions have been systematically destroyed in this process. It seeks to prove that the Welsh have not suffered from class division and have always presented a united Welsh front against the English.

This type of propaganda is specifically designed to encourage class collaboration and to create internal divisions in the British working class on racial and sectarian lines, whilst the bourgeoisie strengthens itself in the EEC.

A look at Welsh history will show that the Welsh workers had a common British birth out of capital, have never ’collaborated’ against any section of British workers on sectarian lines and therefore have a common British interest in proletarian revolution as a solution to British capitalism and its ills. Though there may exist regional inequalities in Britain, there has never existed English colonialism, only British imperialism.

Wales, like England, was created into a whole by first the Roman’s, and then the Normans under feudalism. (Plaid describes the years 400-1284 as the “Period of independent Welsh kings and princes” and states that Wales successfully defended her integrity against the Normans for over 200 years). From 1400-1415 Owain Glyndwr’s rebellion was, according to Plaid, “against English oppression”. In fact it was part of a concerted effort in favour of the Yorkist Henry IV in the Wars of the Roses, and the beginnings of the Tudor line in 1485, and at the close of the Wars of the Roses, it brought to the throne the only indigenous monarchs ever to have sat on the throne – and they were Welsh. In fact the hated 1536 Act of Union described by Plaid “as a destructive policy of the British Government” was instigated by a Tudor, Henry VIII.

The Act of Union was the foundation stone of the infant capitalist state: as Marx said ... primitive capitalist accumulation began in the 16th Century. The Act rationalised property rights in Wales, and the judicial system and the outlawing of Welsh in official circles was avidly seized on by the Welsh squire class to cheat and evict Welsh peasants from land. No tears or morals were – present here and no loathing existed in using ’English Law’ to effect bourgeois gain. The end result of these evictions was the 1601 Poor Law and these movements were not confined to Wales.

The birth of capitalism in Wales corresponded with the growth of industry throughout the rest of Britain. The continued influx of evicted labourers off the land, due to enclosure, provided a ready supply of labour for the developing iron industry in the northern reaches of the South Wales coalfield around Merthyr, which also offered large iron ore deposits. This was the era of the ’Big Five’, and created the largest town in Wales out of Merthyr Tydfil. It’s pre-eminence in 1758 continued into the next century with names like Guest of GKN coming into being. This same pre-eminence was reflected around Swansea by the copper smelting industry – unrivalled throughout the world in the latter half of the l9th Century.

These developments drew not only indiscriminate capital but also drew in a varied workforce of Scottish, Irish and English migrant workers to the South of Wales. The growth of industry, particularly iron, later steel and coal, is reflected in the population trends. In 1801 the population of Wales was half a million equally spread between North and South, but by 1851 the two industrial counties of Glamorgan and Monmouth outnumbered the rest of Wales put together, and this shift was hastened by the development of the coal and steel industry in their own right.

The imbalance in industrial development, still marked today, between the South and South-East corner of Wales and the central and Northern rural areas, had come into being. The growth of railways and communications in general underlined this split, the central Welsh hills forming a barrier to economic unity of Wales but cementing the integrity of the British economic unit.

In fact in the latter half of the 19th Century the ironworks of Merthyr moved south to the coast as the iron ore deposits failed. It was at Swansea that Siemens carried out his innovations to the steel-making process, and Cardiff grew up as the major city of Wales on the valleys coal trade. Geography, not English colonialism, created the economic links and ties of the two sections of Wales. The development of industry in the South not only drained the population of the rural areas of Wales but drew in a vast immigration from the rural area of S. W. England and from those people dispossessed and harried by British capital in the Scottish highlands and Ireland. The Welsh proletariat is indeed a joint product of British capitalism, and its joint struggles in reaction to capitalism’s attacks have been indiscriminate and have never, as the nationalists would have us believe, been narrowed to any sectarian or racial division.

A short look through the major British working class struggles – will show that the South Wales and North East Wales proletariat were to the fore; this is the unified bond the poison of nationalism intends to destroy. Some examples include:

Robert Owen and the General National Consolidated Trades Union – Owen was a Welshman.

1831 – in response to the working conditions in Merthyr, a strike followed by a riot after troops were brought in resulted in the taking over of the town and the red flag being raised.

1839 – Chartists – Llanidloes was taken over and an attack on the garrison at Newport staged.

1830 – Workhouses – Rebecca riots against both turnpikes and the workhouses and the wider burning and attacks on landlords over rents and the security of tenure (Captain Swing).

Unions – the miners in South Wales were in the forefront of the Miners Federation with many long and bitter struggles against the Welsh coal-owners.

1900 – Merthyr elected first Labour MP – Keir Hardie.

The list could be extended.

The evidence so far brought forward gives the lie to the fact that a Welsh economy was destroyed by English capital and that the division of Wales was due to this process. Wales suffered as did the rest of the country from the anarchic development of British capitalism, in which Welsh as well as English played their role.

The industrial proletariat has never been fooled by racial origin in its struggle against capitalism.

We have seen that Wales is an integral part of Britain and being so it is false to posture an independent Wales as Plaid Cymru does. Their policy to the multinationals shows that there will be no change of economic systems. The Welsh Language Societies have no policies other than the defence of the language. Whether language movements are capable of doing good work in helping to save from extinction the precious national history, language and characteristics of our people, is not in question; the danger is of neglecting vital living issues and of crystallizing nationalism into a tradition – this can never be strong enough to be a force for a successful revolution.

Any country’s language and culture suffers under capitalism. Many nations during the late 19th Century became part of a European movement struggling to restore their languages. Many were successful (Lithuania, Estonia, Finland etc.) but the most successful because of grasping the real enemy and dealing with it, was Albania – the only Socialist country in Europe today. Unless the decline of the Welsh language is seen in the same light as capitalism’s general attack on British culture and industry through its holders and guardians, the working class, then the language movements will end up isolated from their cause and means, the working class.

Let us have a look at a former potentially revolutionary period. At the peak of struggle in the early 1920’s, following nearly two decades of growing working class struggle, the Clyde Shop Stewards movement, the deportations, imprisonment, Churchill’s ordering the tanks into Glasgow in the 1919 strike, the mutinies of the troops in Glasgow’s Maryhill Barracks, the Marxist leader John McLean ended up in a cul-de-sac of nationalism, eventually to be broken and killed by the state.

We must never forget this sad and negative example. What is clear in Britain is that there is a national capitalist class and opposing it a national proletariat, this; nevertheless possessing areas of distinctive cultural traditions. Through a thorough knowledge of the traditions and characteristics of all sections of our class, working class unity in today’s period where revolution is on the agenda, is for us to achieve, treasure and preserve.

It is clear that capitalism cannot afford the British working class as a united force in the world today and it is out to destroy it. They intend to destroy our nation which is the creation of our own working people at the very time that for Socialism to break through, we will have to bring into full play, and muster towards revolution, all areas of this most proletarian country. EEC membership, devolution, IMF and World Bank agreements are all part of British capitalism’s counter-revolution on the political front.

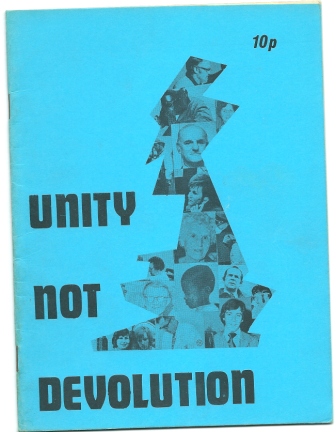

The British working class whether in Scotland, Wales or any other part of Britain should declare a resounding NO to devolution, or any other policies which will come in the future, aimed at dividing and weakening our class. We as Marxist-Leninists are totally opposed to divide and rule. -We have to make the ruling class’s divide and rule inoperable by our unite and liberate.

The task before us is a vast one – the workers of Britain need to take on the entire ruling class without regard for ethnic divisions. As we state in our Congress ’76 pamphlet, “Recrimination and division within our class is a constant danger. Disunity is the high road to further defeat”.

Working class unity makes it impossible for the capitalists to go on in the old way of divide and rule. Working class unity enables us to combine our tactics for defending our class with the strategy of liberating our class. Working class unity is revolutionary.

Chwyldroad nid Trosglwyddiad.

We are for REVOLUTION not DEVOLUTION.