First Published: 1986.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The significance of the miners’ strike 1984-85 has not been fully comprehended, let alone absorbed, by the Labour Movement. Hence this pamphlet.

Like any other pivotal conflict, this one contained episodes of heroism (and instance of betrayal) that have been recounted many times and will not be told again here. The miners’ true achievement was political. They began to change the climate of opinion in Britain, they opened up divisions in Thatcher’s government that have not healed, and they revealed This latter-day would-be “populist leader” as a populist without popularity, a leader with no one to lead.

Their struggle met with a surge of support from every corner of Britain. But it also revealed grave weaknesses among workers both at the time and in the aftermath. Many still fail to appreciate the nature and gravity of the new situation facing the working class. Many fail to see how to fight.

Everyone hailed the miners’ part in the victory over the Heath government a decade earlier. Their great contribution in the protracted struggle against Thatcher, much deeper in its significance, has eluded some.

Britain is unique among capitalist countries. As the first industrial country with the first proletariat and the first trade unions, its development has always been in advance of others. There is no model for Britain to follow.

This is true for the capitalist class as well as the working class and their respective institutions. The transformation of feudalism into capitalism, consolidated by revolution in the Seventeenth Century was an advance of unmatched proportion and quality, relative to which all subsequent economic development has been downhill.

Today, capitalism is in unrelenting, absolute decline. It has gone full circle; from land enclosure to factory closure. Its incessant need to develop new productive techniques, create demands and satisfy wants, its very raison d’etre, is today its Sword of Damocles. It no longer can cope with its own development. New technology, information technology, high technology, the products of working class ingenuity, far from being the saviour of capitalism are being employed to accelerate closure, continue and exacerbate the decline.

Absolute decline did not commence with Thatcher’s election in 1979. It long predates Thatcher. Yet Thatcher’s regime created a new situation in Britain. Whilst previous governments, Wilson’s, Heath’s, Callaghan’s, attempted to cope with decline, Thatcher not only recognised its absolute nature, she embraced it and welcomed it. Her policies are simultaneously driven by it and driving to it, an orgy of destruction far beyond anything contemplated even by her supporters and the masters who put her in power.

Thatcher sees no future for capitalism in Britain; hence the increasingly desperate attempts to destroy the remnants of manufacture, technological know-how and industry, hence the sale of public assets, and the handing over of British advanced industry to the US and Japan.

Given this situation, which way to struggle?

Thatcher’s philosophy has imbued all aspects of government policies and everyday life in Britain.

Everyone, every worker and every trade union, is being confronted with a fundamental choice: accept or reject Thatcher’s philosophy.

All issues from tea breaks to redundancies, from demarcation to wages at once arise from and lead to that basic choice of philosophy. Those who accept Thatcher’s strategy are reprieved with temporary peace, like lemmings enjoying the walk to the cliff edge. Those who reject absolute decline inevitably come face to face with the Government.

Tory and Labour governments alike have acted in the service of the bourgeoisie - this is an historic fact. In the past two decades we have witnessed Labour’s “In place of strife”, the Tory “Industrial Relations Act”, “counter inflation” policies, wage restraint and so on. All were attempts to shackle the working class, undermine trade unionism and reduce standards of living. State legislation to regulate trade unions and control wages gave political character to working class struggle to defend living standards. Under Thatcher such struggle is assuming a more fundamental character, a struggle for power.

When no lesser object than state power itself is at stake, the Government cannot shift, let alone give way. This is the character of all tyrannies as they struggle upwards their inevitable end. Thatcher’s embrace of absolute decline, her strategy of destruction of’ the manufacturing base was her strength, her claim to the political leadership of the bourgeoisie. Today, that very strength is turning into its opposite, to which the carefully cultivated Thatcherite edifice is becoming vulnerable. She came to power with the promise of ridding Britain of trade union power; not unlike Hitler. That this in Britain means nothing less than the destruction of the country as an industrial nation became clear only after her policies had been put into effect.

While Thatcher welcomed and hastened this destruction she began to alienate sections of her class, her party, and her cabinet. Here was the classical dilemma of a dying ruling class which creates a saviour only to find its creation uncontrollable. Heath was always in opposition but then came Lord Stockton. Then there were the captains of industry. Today the opposition includes cabinet ministers as well as ex- cabinet ministers. Her leadership is openly challenged by any Tory MP capable of making a coherent speech.

The advent of Thatcher brought ideological clarity to the ruling class. Attacks on wages, jobs, trade union and democratic rights have all been conducted by previous governments. Thatcher welded these issues together and has launched a coherent onslaught, derived from and ’directed by a single strategy of sustained decline and destruction.

The response by the working class has not matched the ideological clarity of the ruling class. Until the miners began their struggle in 1984, few workers had grasped the nature of the new situation under Thatcher. Although some regiments had entered the fray, in general the army of the working class decided to keep their heads down until the shooting stopped. Clearly, the methods of the sixties and seventies, of guerrilla struggle and the fight for a limited objective, of relatively little sacrifice, were no longer adequate.

The miners launched a new phase of class struggle, protracted struggle. In the first place, they fought because they had to. They dug in and said, “we stand and fight”.

Their struggle was for the very survival of their industry. But defence turned to attack as the miners issued a direct challenge to the heart of Thatcher’s philosophy. They demanded a future.

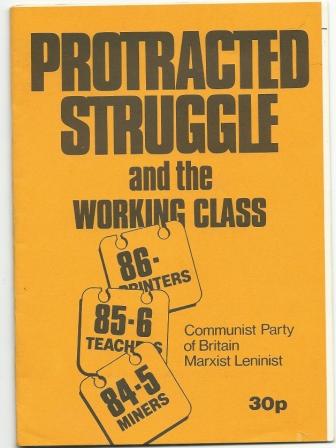

Though prolonged and arduous, the essential character of protracted struggle is not its longevity. Its essential character is ideological. The miners would not have fought so hard with such determination and for so long without the ideological commitment to a future, a future denied to them by Thatcher. They see a future, want a future, demand a future. It is this understanding which underlies the miners’ strike 1984-85 and the teachers’ struggle 1985-86, and the print workers 1986.

The school teachers of Scotland and in England and Wales followed the path of protracted struggle blazed by the miners. This in the teeth of claims from throughout the political spectrum that the miners had “failed”.

And now the print workers 1986 pursue their fight for survival.

Our response must be as coherent and as clear as the attack is comprehensive and penetrating.

The miners’ familiar demands for higher pay, better conditions and no closures were linked together in a battle to save the mining industry. It was “pits, jobs and communities”, and the women joined the men.

Similarly with the teachers; it began over pay, but then pay and conditions were linked in the campaign to save education. Parents joined the teachers.

Issues linked together and winning ever-broadening support; such is protracted struggle.

The protracted struggle of today has emerged from a period of guerrilla struggle. It was the distinctive contribution of the teachers to show that protracted, struggle does not deny guerrilla struggle. There is guerrilla within the protracted. The teachers never embarked on an all-out, indefinite strike. They preferred short strikes at selected times and in selected areas arid they employed sanctions, which caused maximum impact with minimum cost, classic guerrilla tactics.

Guerrilla methods were employed but the objective of reversing the long-term erosion of teachers pay was never abandoned. The fight goes on.

The characteristics of guerrilla struggle are localism, limited objectives, and isolation. In protracted struggle localism gives way to a unified strategy and a unified command. Local demands are joined in a single campaign against the enemy.

Protracted struggle is not an end in itself. Its objective must be to halt Thatcher’s offensive, drive her back and throw her out. Protracted struggle only makes sense if it paves the way for a higher phase of struggle. There is a need for struggle on all fronts. No single section of workers can be left isolated. As each regiment engages the enemy on its own front, the creation of a common ideology, a common strategy and command is but a natural development.

Absolute decline has thrown the question of revolution into the centre of working class struggle. By embracing absolute decline Thatcher has settled the age-old question, “Can workers live with capitalism?”

The answer must now be clear to all. For with sustained decline as the declared policy of the Government, with the destruction of manufacture as the crucial step, with capitalism turning upon itself in a frenzy of destruction, the only future for workers is the destruction of capitalism itself.

Long before the strike began, Government policy towards coal was one of progressive closure and decline. The tool, MacGregor, had his brief directly from Thatcher. His task was to repeat the butchery he carried out in British Steel where, with a token resistance from the workers, he succeeded in chopping 100,000 steel jobs and capacity by 60%. Whole towns were reduced to empty shells practically overnight.

A different attitude confronted MacGregor when he was appointed as Chairman of the National Coal Board on September 1, 1983. The build-up to fighting closures and saving the coal industry which the National Union of Mineworkers leadership had been engaged in over a number of years began to show results. An NUM Special Delegate Conference on October 21, 1983 voted for a ban on overtime against pit closures and the 5.2% pay offer. The link of pay and closures was of strategic significance, laying the ground for the fight for industry to follow.

A tense period then ensued with the miners still reluctant to challenge the NCB’s Government-inspired policies. On March 1, 1984, in the most provocative action, the NCB announced the closure of the Cortonwood pit in Yorkshire, a pit that still had five more years of productive capacity, an example of industrial hooliganism that characterised the management throughout the dispute.

In response, miners in Cortonwood walked out, the spark which started a prairie fire. They were followed by 55,000 Yorkshire miners. The strike quickly spread to Kent, South Wales and Scotland. The one area that refused to join in and kept on working throughout the strike was Nottingham. Irrespective of the call by their own leadership as early as March 18 to join the strike, the Notts miners, with honourable exceptions, kept faith with their reactionary history, preferring to follow the scab Lynk and his ilk.

The miners took their case to the working class. They asked for donations to feed the strikers and their families, and they were not disappointed. Miners support groups sprang up everywhere. Money was collected at every trade union meeting, in the streets, wherever workers passed. The case of the miners was unassailable in spite of the unrestricted use of the mass media to undermine their argument and their strike.

Support came from abroad with train and lorry-loads of food, clothing and presents for the children at Christmas. The more the Government stepped up its action against the miners the greater the support the miners received. The courts were used to cripple the NUM financially. Huge fines were imposed and their assets were seized. But the union kept going and the strike went on.

The trade unions responded to the miners’ strike by giving support and assistance. The two rail unions, the NUR and ASLEF, blacked all movement of coal and continued to do so till the end. The Government never dared to take the unions to court over their “unlawful secondary action” for fear of opening a second front.

The seamen and the Transport and General workers also blacked coal, although in the case of the latter the blacking was largely ignored by lorry drivers who carried lorry loads in and out of steel works and power stations, ignoring the pickets, terrorising road users and endangering life. Scab non-union drivers also carried coal, lack of organisation by unions having permitted the growth of these cowboys. The mass picketing that followed the transfer of coal from rail to road was met with draconian measures by the police in stopping movements of miners from one county to another, the deployment of local police forces through the “national reporting centre” in London, attacking and arresting pickets , terrorising pit villages and assuming extraordinary powers of stop and arrest. No mercy was shown. No mercy was or should have been expected.

The Iron and Steel Trades Confederation (ISTC) and the electricians’ union (EETPU) spurned the approaches of the NUM. The steelmen, having succumbed to MacGregor and accepted the destruction of their industry, stayed loyal to their betrayal and announced their willingness to accept coal from anywhere. Steel workers in some plants fought to keep alive the spirit of the shattered Triple Alliance of steelmen, railmen and miners (ISTC-NUR-NUM).Meanwhile, General Secretary Sirs of the ISTC did all he could to kill it. The original agreement between the NUM and the ISTC was for coal deliveries to keep the furnaces just ticking over British Steel took the offensive and Sirs was glad to capitulate. The hundreds of lorry loads of coal and coke deliveries were never used by BSC, but they were the justification for the police to be unleashed.

Within the coal industry itself, the deputies union (NACODS) had an opportunity to clear their conscience and take a decisive stand against Thatcher but they turned it down. Having voted overwhelmingly for a strike, the leadership quickly called it off on the pretext of an acceptable pit review procedure. The rank and file did not revolt and their vote was exposed as a bluff which was seen as such and called by Thatcher. The deputies, to their discredit, continued to collect full pay for staying at home. The miners, grateful for any support, were pleased that the NACODS members made no serious attempt to cross picket lines and start production.

The psychological warfare employed by Thatcher was to create, or be seen to create, split trade unions. The creation of the Midlands fifth column (embracing all trade unions in coal power and rail) was one example, the “neutralising of the ISTC another, the use of the EETPU another – though Fleet Street electricians came through, and EETPU stewards on the Yorkshire power stations struck twice on supportive regional days of action. In the North East and North West no power was contributed to the national grid despite scab deliveries of coal because TGWU members on site stopped it dead.

The miners’ strike was a challenge to capitalism’s absolute decline. The miners demanded a future for coal, for themselves, for their children and their communities. Capitalism demanded destruction and decline. It was a clash of two outlooks, two philosophies.

That there can be no future under capitalism is fully realised by Thatcher, though not yet fully comprehended by workers. The future the miners demanded layout of capitalism. They fought for their industry because they could not fight for revolution. The only way to the latter is by fighting for the former.

The miners thus were in irreconcilable collision with Thatcher. To win, Thatcher must go. For that, more than gestures· of support and solidarity were necessary. The need was for a second, a third and a fourth front against Thatcher. Far from opening these new fronts for higher wages, better conditions, more jobs and, above all, for investment in industry, trade unions preferred to watch from the sidelines. Some even took advantage of the Government’s preoccupation with the miners to “win” pitiful increases in pay and promises about jobs.

Throughout the year-long strike, every union had an opportunity to open the fight on their own front; they preferred not to. The only exception was the dockers’ leadership. They called the dockers out on strike on two occasions, in July and August. Their strength, both organisational and ideological, was insufficient to sustain a second front under the hostile conditions endured by the miners.

The miners challenged absolute decline and rocked Thatcher. In doing so they made great sacrifices. The Government suffered immense physical loss, but its chief loss was political. This becomes evident as we witness the dissension within the cabinet and the deep discontent within her party. The roots of the Thatcher’s weakness lies in the walkout by the miners in Cortonwood.

The railmen were geared up to take strike act ion following the breakdown of pay talks in June 1984. At the eleventh hour, and at the direct instruction of Thatcher, a better offer was made. To their eternal shame, the railmen’s leaders could do nothing other than recommend acceptance and call the strike off.

They failed to show the same carry as those they were fighting hard to support. The question of “no settlement with Thatcher” was never raised, let a lone understood. The railmen repeated the same exercise three months later, preferring to settle upon promises of future jobs than to open that vital front.

The miners went back to work with heads held high, banners flying and bands playing. Thatcher was unable to gloat. There was no agreement, no settlement, which sums up the balance of power between the contending classes.

The tactics adopted by the NUM leadership were a product of the strategy of the strike, the fight for their industry. In that they could not be faulted those who preferred other tactics and advised compromise and settlement tacitly accepted industrial decline.

Before the miners’ strike ended, the school teachers in Scotland began their campaign for an independent salary review. School teachers in England and Wales soon followed with a protracted campaign to improve their pay and protect conditions. Seemingly different, the teachers’ struggle 1985-86 is, in essence, the same as that of the miners – both fighting to save Britain from Thatcher’s destruction in one case coal, in the other, education, both vital to the industrial future of Britain.

Despite continuing difficulties, the teachers achieved a remarkable degree of unification within their own ranks. The Educational Institute of Scotland and the National Union of Teachers in England and Wales succeeded in embracing organisations whose only reason for existence hitherto had been their opposition to progress. So effectively did the teachers present and argue their case that even head teachers’ organisations for a long time were dissuaded from opposing, and even gave a measure of support.

A major feature of the teachers’ struggle, which appealed to “white-collar” and service workers at large, was the assertion of professionalism.

Professionalism is as central to the services as skill to manufacture. In both the expert hand and brain is applied to the task of the moment to produce something of quality, not because market forces demand it but because pride in work, the dignity of labour requires it to be done. As such, it is anathema to capitalism which tries to de-skill, de-professionalise all work, thus to reduce the value of labour power and to force all workers into a pool of interchangeable unskilled labourers.

What distinguishes a “profession” is not the nature of the work itself but the belief of workers in it. They will fight to the end to preserve and protect it. This is their castle, others keep out! And within the walls only work of a certain quality is tolerated.

Thatcher attacked the teachers’ action as “unprofessional”. The truth is t he very opposite: by showing their commitment to education. The teachers did more to establish teaching as a profession than a hundred years of respectable docility. Their fight was about securing professional level of pay. But other issues that arose during the action - of conditions of work, of the quality of education, of changes in the examination system are necessarily professional issues that can only be settled by the profession.

The task of the public, guilty of long having taken education for granted, is to demand professional standards from the profession, to ensure that its members receive adequate remuneration, and to give them the buildings and resources to do the job.

So well have teachers handled their campaign that parents, for the first time since the beginning of state education, have become aware of their responsibility and have taken up the cudgels in support of the teachers. All this to the evident dismay of Thatcher who attributes to the rest of the population her own philistinism and narrow, short-term selfishness.

It was the protracted struggle of the teachers that achieved this transformation. Parents, formerly unorganised, are now becoming organised, not to oppose the teachers as Thatcher hoped, but to demand professional rates of pay for teachers as the key to the preservation of education.

For three decades after the War the initiative in class struggle world-wide was with the working class. The point of origin can be traced back to the Battle of Stalingrad, the decisive moment of defeat of the forces of capitalism in their quintessential form of Nazism by the forces of socialism in their quintessential form of the Soviet Red Army.

In these decades there were two great currents of advance – the expansion of the socialist camp and the victories of national liberation over colonialism in many countries. Vietnam’s comprehensive defeat of USA imperialism was the epitome and culmination historical of both these currents. The spirit of the times was summed up in Mao’s slogan, “Revolution is the main trend in the world today”.

No comparable advance occurred in the older capitalist countries. What concerns us most, it did not occur in Britain. Here also, many gains were made in many struggles and the working class army was enlarged and strengthened, not least through the founding of the Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist). The Labour Party, though only in power for half this period, became the reforming architect of capitalism, putting into effect policies which, though to some degree undermined by Tory governments, were never reversed. These gains however, never seriously challenged the capitalist system; the initiative that workers held was squandered.

Thatcher’s election in 1979 signalled the end of this phase of relative progress in Britain and the onset of a phase of out-and-out reaction. Counter revolution is now in temporary ascendancy in Britain and the world at large.

The prospect now before us is appalling. We have the hag-ridden Thatcherite nightmare of an impoverished, de-industrialised Britain, dependent on the fickle hills of the tourist trade, our sons as waiters and our daughters as prostitutes, a dependency of the USA – a Puerto Rico without the sun.

Others suggest that Britain will take her place as one of the “United States of Europe”; the economic details are never spelled out, but the one certainty is that it would mean an end to 1000 years of successful defence against conquest by our neighbours.

Such subjugation of the working class is unthinkable.

Yet others dream of a return to the 50’s or 60’s presented now as a golden age of prosperity and full employment. Capitalism’s absolute decline makes this an unattainable utopia: we must move forward for we cannot go back.

Protracted struggle is necessary for the survival and recovery of a working class. It is serious, sober and long-term. There can be no theory of a “big bang”. It must be class action, united action. No more shall others sit back and watch as they have done with the miners and the teachers. Still less shall they seek to exploit the valour of fellow workers. Every front must fight.

Protracted struggle requires an end to squabbles and petty divisions within the Labour Movement, such as attempts to split the TUC, or the jockeying for position of various sects within the Labour Party. No more shall workers permit fashionable slogans about race and sex to usurp the fundamental issue of class. The parts can never be greater than the whole. Only in the course of class struggle and revolution will all forms of chauvinism and other distortions of thinking and feeling be at last eliminated.

All struggle must be directed against Thatcher – fights to defend and rebuild industry, education, the health service and other services, whatever their local target, have the removal of Thatcher as their goal. In every local or by-election, defeat for the Conservative candidate is defeat for her. Vote Labour to get Thatcher out.

Return to the basic elements of working class struggle, the fight for wages. The defence of skill, the dignity of labour, the defence of professionalism are rocks on which protracted struggle can be founded.

Marxists are above all realists. The only practicable solution is the destruction of capitalism and the rebirth of Britain as a civilised country in which all will work because work is life’s prime need. Industry and education shall survive! Out with the wreckers! Out with Thatcher! Protracted struggle win!

May 1986