First Published: Unity, Vol. 5, No. 5, May 26-June 8, 1982.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

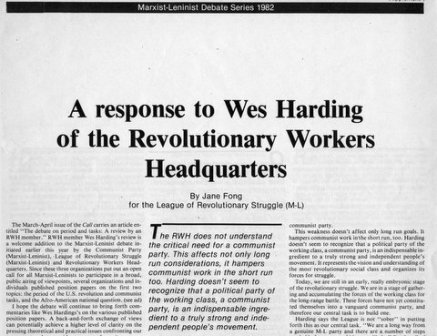

The March-April issue of the Call carries an article entitled “The debate on period and tasks: A review by an RWH member.” RWH member Wes Harding’s review is a welcome addition to the Marxist-Leninist debate initiated earlier this year by the Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist), League of Revolutionary Struggle (Marxist-Leninist) and Revolutionary Workers Headquarters. Since these three organizations put out an open call for all Marxist-Leninists to participate in a broad, public airing of viewpoints, several organizations and individuals published position papers on the first two topics: the period of the U.S. revolution and communist tasks, and the Afro-American national question. I hope the debate will continue to bring forth commentaries like Wes Hardings’s on the various published position papers. A back-and-forth exchange of views can potentially achieve a higher level of clarity on the pressing theoretical and practical issues confronting our movement and open wider prospects for unity.

Harding raises two main disagreements with the League’s position paper on the period and communist tasks, Repression, Reaganomics, War and Revolution. His principal disagreement, it seems, is with the League’s view of party building as the central task of communists today. Harding argues that the League takes party building as its starting point, not the “objective conditions” and the “actual struggles of the American people.” He believes that placing party building as its central task leads the League to see the advanced elements from the mass movements as those who are more open to being recruited by communists, rather than those who would play the “biggest role in national resistance to Reagan and his class.” Harding says that he thinks because of these reasons, “the LRS puts its organizational needs above those of a sober analysis of the needs of the people and the movement.”

The other disagreement concerns policy on where communists should concentrate our forces at this time. I would like to respond to each of the points and elaborate some on the views the League published in our series of debate pamphlets.

In the League’s debate paper, Repression, Reaganomics, War and Revolution, we present our assessment of the stage of development of the U.S. revolutionary struggle. We lay out what we think our principal tasks should be given this stage of development. The revolutionary forces in the United States are relatively weak at this stage. While the system of U.S. imperialism has been in extended and serious crisis, the enemy is tremendously powerful and the system is not at, or near, a stage of collapse. The majority of people do not yet see the need for revolutionary social change.

The people’s struggles are developing, though, and in some cases are quite vigorous. There is increasing struggle against the ruling class’ attacks against the people’s standard of living, more repressive government policies, stepped-up national oppression and the growing war danger posed by global superpower contention.

Socialism is not an immediate goal. The struggle to overthrow the class enemy and establish a socialist system will be very protracted in this country and its exact course can’t be predicted. We shouldn’t project socialism as a quickly achievable goal, but we do have the immediate task of developing a clear socialist alternative to the ruling class and an independent people’s movement.

In the League’s A Response to the RWH’s Realignment, Reagan and Our Tasks, we pointed out a fundamental weakness in the RWH’s approach to our tasks today. They say our main task is to build an anti-Reagan Administration front without regard for how we should gradually and systematically build up the people’s consciousness and strength for revolution and communism. Since this is not in their perception, they also belittle the need for an independent working class or socialist alternative, perspective, programme and communist party.

This weakness doesn’t affect only long run goals. It hampers communist work in the short run, too. Harding doesn’t seem to recognize that a political party of the working class, a communist party, is an indispensable ingredient to a truly strong and independent people’s movement. It represents the vision and understanding of the most revolutionary social class and organizes its forces for struggle.

Today, we are still in an early, really embryonic stage of the revolutionary struggle. We are in a stage of gathering and accumulating the forces of the working class for the long-range battle. These forces have not yet constituted themselves into a vanguard communist party, and therefore our central task is to build one.

Harding says the League is not “sober” in putting forth this as our central task. “We are a long way from a genuine M-L party and there are a number of steps needed before one would become likely.” But for all of his stress on the need to be “sober” and “concrete,” there is nothing in his article about what concrete steps he advocates. His rhetoric can sound very glib, but underneath there’s nothing of substance.

RWH does, however, advocate something. They advocate building a Marxist-Leninist organization that would be stripped of its revolutionary principles, goal and character. They say social democrats and centrists can be included in a Marxist-Leninist organization. (Reaganomics, Realignment and Our Tasks, pg. 15) In the League’s view, such an organization could no longer base itself on the theory of Marxism-Leninism and would rapidly become an intellectual debating circle for various non-Marxist trends. It is not the kind of organization that could attract working class people.

Are these the kind of “steps needed before a party would become likely?” Such a “step” as the RWH is advocating would serve to liquidate, confuse, demoralize and disperse the forces that comprise the communist movement at this lime. It would set back the struggle for a true communist party for a long time.

It is true that there has been confusion in the communist movement in the past about how to build a communist party. Some have thought it meant merely grouping some forces together and declaring themselves the party, apart from acquiring a concrete grasp of conditions in the U.S., distinguishing clearly a Marxist-Leninist line and programme, building stable and deep ties among the masses, winning over the advanced elements to socialism and uniting the majority of Marxist-Leninists. The alternative to these wrong conceptions, however, is not to negate party building or what amounts to the same thing – putting party building off for such a long time into the future that one thinks it is irrelevant today.

A more correct approach is to make party building a real, living question in every aspect of our work. To make party building our central task doesn’t mean that it is our “only task.” It doesn’t mean that all we should do is go from one Marxist-Leninist conference on party building to another. It does mean making it a pivot for our day-to-day activities.

For example, if we proceed from the assessment that the revolutionary movement is in an early, embryonic stage of development and needs to gather its forces and prepare for the formation of a party at the correct time, then it is obvious that we must pay particular attention to winning over the fighters in the mass movements most open to socialism. This should be part of our work in helping build an independent people’s movement. This process furthers the fusion of the communist and mass movements. It strengthens both. The advanced elements give strength, vitality and lifeblood to the communist forces. When they embrace the scientific theory of Marxism, apply it and work as part of a unified, communist organization, they become better, more effective fighters in the mass movements.

At a later stage of the revolutionary struggle, when the revolutionary forces are stronger, the consciousness of the people higher and conditions more ripe for revolution, it would be correct to go out and try to win over the majority of the working class to socialism. If we confuse the two stages, this will lead to many problems in our work.

In the experience of the League, this approach to our revolutionary tasks today is more in keeping with a sober analysis than the approach proposed by Harding and the RWH. His assertion that the League “puts its organizational needs above those of a sober analysis of the needs of the people and the movement” comes from a serious misunderstanding of what the needs of the people really are. The League believes that the people need revolution, ultimately, to solve the basic contradictions facing their lives. We are committed to building up the organized forces of the working class for revolution, not “ourselves.” To say that the building of a communist party is “placing organizational needs” above the people’s needs is just another indication that the RWH is losing sight of who we are fighting and what we are fighting for.

Perhaps the type of cynicism that leads one to say party building is “placing organizational needs” above the people’s needs comes, in part, from Harding’s concern for the “survival, if not for the whole trend, at least a sizable part of it.” The impression one gets is – how can you talk about building a party when we can’t even keep ourselves together in our present state?

The past few years have witnessed a considerable growth of cynicism in certain sections of the communist movement. The effects have been extremely damaging. It has been one of the many factors causing the loss of some forces to the revolution and setbacks of whole organizations. But that is not the only effect. Within some revolutionary organizations, a mentality has developed where “our survival” is talked about devoid of clear revolutionary principles. When this mentality and atmosphere have come to dominate an organization, anything is justified to keep one’s organization “together,” including abandoning a commitment to revolution and a clear vision of the requirements for revolution in the United States. It doesn’t save our movement, but causes disorientation and pessimism. Whether intentional or not, it amounts to placing one’s “organizational needs above those of a sober analysis of the needs of the people and the movement.”

I believe that among the various communist organizations and groups that emerged from the decades of the 1960’s and 1970’s the League today is relatively more consolidated and stable because we have always tried to “proceed from the actual terms of the struggles confronting the American people, building them up, developing line through this, and on that basis building up Marxist organization” – to use Harding’s words. It is ironic for him to say that the League’s emphasis on party building “leads away from the steps that could consolidate, stabilize and define our trend.”

The League and its predecessor organizations have been able to develop relatively more stable, ongoing mass work and ties – in many cases working in a particular struggle or mass organization for over 14 years – because of our constant attention to the needs and struggles of the people. The League has continued to develop this work, while at the same time calling on all Marxist-Leninists to struggle for communist unity and persevere in party building. I think this does more to help stabilize, consolidate and define a Marxist-Leninist trend in the United States than the liquidationist steps proposed by the RWH.

The second major disagreement Harding raises is over the League’s policy on where communists should concentrate our forces in mass work. We stated in Repression, Reaganomics, War and Revolution that we believe communists should concentrate our forces in the lower stratum of the working class and among the oppressed nationalities.

Our concentration policy is based on our analysis of conditions in the U.S. and our estimation of what will be needed to develop the revolutionary struggle of the people. We are in the process of deepening our study and analysis of conditions in the U.S. at this time and trying to develop a more sophisticated line and strategy. The policy on where to concentrate work is part of the strategic perspective we are developing.

We believe that in the working class, communists should concentrate our forces in the lower stratum, though not exclusively. We identified three sectors in the lower stratum where we place a priority in allocating forces: the unskilled production workers in basic industry; workers in light industry and manufacturing, particularly in the unorganized South and Southwest; and workers in the lowest paying, labor-intensive industries like sweatshop production and farm labor. The lower stratum includes both unionized and nonunionized workers.

The workers in these sectors have been less affected by the privileges of imperialism, are less connected to the labor bureaucrats, and in general face more difficult living and working conditions. These factors make them more inclined to struggle. By placing a greater concentration of forces there, communists can make the greatest gains in rooting socialism in the working class and winning the advanced in order to be able to develop the labor movement in the U.S. in a militant and revolutionary direction.

The lower stratum of the working class is of tremendous strategic importance, too, because oppressed nationality workers are concentrated here. The oppressed nationality workers are part of the multinational working class and also comprise the vast majority of the peoples of the oppressed nations and oppressed nationalities inside the United States. They will occupy a crucial position in helping forge the strategic alliance of the working class and national movements in the U.S. revolution. They will raise the national democratic demands of the oppressed nations and nationalities within the labor movement; and they are the most revolutionary class within the national democratic movements themselves. All these factors point to the centrality of the national question in a strategic view of the U.S. revolution.

Historically, the lower paid and most oppressed sectors of the working class have played, at crucial junctures, a critical role in determining the tempo and level of struggle of the labor movement. Some examples were the immigrant textile workers in the early twentieth century; the unorganized industrial workers in the 1920’s and 1930’s (many of whom were European immigrants); the Afro-American auto workers in the 1960’s; and Chicano and Mexican farm workers in the 1960’s and 1970’s. They will continue to do so in the future.

In addition to the lower stratum workers, our concentration policy includes the oppressed nationality movements. Any communist strategy for revolution in the U.S. must take into full account the role the national democratic movements will play. The late 1960’s showed the power of the Afro-American liberation movement in U.S. domestic life as well as internationally. We live in an imperialist superpower containing two distinct oppressed nations on its borders: the Afro-American nation in the South and the Chicano nation in the Southwest; and with several oppressed nationalities, including the Chinese, Japanese, Puerto Rican and others. Compared to the labor movement, it is important to realize that the oppressed nationality movements in this country are still the relatively more active and conscious sector.

We realize that in identifying the lower stratum of the working class and oppressed nationality movements for concentration of our forces, we are not following what many may see as an “orthodox” view. Harding’s view is closer to the traditional view of many U.S. communists and leftists. His view that workers in the highly unionized, relatively higher paid sectors “have the greatest leverage and potential consciousness” corresponds to a vague, simplistic and dogmatic notion of revolution adopted mechanically from what some think happened in revolutions in other countries. This view holds that the U.S. revolution will happen when workers, mainly in the industrial belt, rise up and “shut down” the economy.

Certainly, the workers in basic industry, especially production workers, will play a major role in the developing U.S. labor movement and in the socialist revolution. The unskilled production workers in basic industry comprise a major sector of the lower stratum workers. The economic position and the high degree of socialization of labor lends the production workers, generally, a sense of power, discipline and organization. The League has always placed a large proportion of our cadres doing labor work among the production workers and within the trade unions in these industries. We have cadres working among the unskilled workers, and also among the semi-skilled and skilled trades. We do not pull them out of the skilled jobs because we want to concentrate in the unskilled sectors.

Harding is wrong in his blanket assertion: that the “highly unionized, relatively higher paid sectors have the greatest leverage” and “potential consciousness” of all U.S. workers. He is also wrong in saying that the “greater amount of oppression and weak union representation also means greater intimidation and hesitation to stand up for basic rights.”

This way of thinking is simplistic and dogmatic. It fails to understand the dynamic and complicated social and political factors that will give rise to revolution in the United States. It looks mechanically at the degree of socialization and unionization as the only factors in giving rise to political consciousness. It relegates to a secondary or marginal role a crucial and large sector of the working class, whose conditions of life and work are most oppressive; whose consciousness of the fundamental problems of capitalism consequently develops relatively faster. The lower paid and relatively more oppressed sectors of the working class, in our estimation, will be a great “lever” in the development of the revolutionary struggle in the United States.

In many instances, the political consciousness among lower paid and most oppressed workers is higher about the system of imperialism and the need for militant struggle. The long-fought and militant struggle of the Chicana women workers at Farah for a union in the 1970’s was an inspirational example that shouldn’t be ignored, belittled or forgotten.

There are also racist overtones to Harding’s statements. Oppressed nationality workers have historically suffered discrimination and exclusion from entering the higher paid and skilled sectors of the working class. While there have been some gains in affirmative action, overall these sectors are predominantly white. To say the higher paid sectors have the “greatest potential consciousness” dovetails with the racist view the labor aristocracy has always promoted that the masses of unskilled workers, as well as immigrant and oppressed nationality workers, are “scum,” “not organizable” and “easily intimidated.”

His view also belittles the role of the lower paid white workers. In the South, for example, we think it is important for communists to develop work among the lower paid white workers in unionized and nonunionized industry. They occupy an important position not only in the economy, but politically as well. The role they take in relation to the Afro-American people’s struggle for self-determination in the future will be a major factor in the forging of multinational working class unity.

The League’s difference with the RWH on the strategic role of the lower stratum of the working class and the national movements in the U.S. revolution has broad implications. We believe the comrades in the RWH have failed to analyze the specific feature of the U.S. revolutionary struggle – the historical, political, economic, geographic and social features which can’t be lifted out of Forbes, U.S. News and World Report or Marxist-Leninist classics.

As we pointed out in the League’s debate paper, we cannot know for sure how the seizure of power will come about in the U.S., but we think “the bourgeoisie in the U.S. will most probably have to be weakened by a combination of uprisings in the imperialist empire, war and domestic struggle. Even with these factors, the proletariat and revolutionary people in the U.S. will have to take the path of armed struggle at the correct moment, that is some form of urban workers’ uprising together with the insurrections of the oppressed peoples and nations in this country. It is even possible that the “evolution will be sparked by a national uprising in the U.S.” (Repression, Reaganomics, War and Revolution, p. 14) Underestimating the role of the lower stratum workers and oppressed nations and nationalities in the U.S. revolution is a tremendous mistake.

Harding concludes his review of the League’s debate paper by way of innuendo, rather than making principled political criticism. He starts by saying he disagrees with the League’s evaluation of right opportunism posing a greater danger than “left” opportunism from a long-term point of view, historically and at present in the communist movement.

But then he says, “My point in raising this is not to all for rehashing debates over which error was primary in the past, nor do I want people to crystallize too quickly over what trends these days are and are not opportunism. But it seems that the LRS misanalysis of the past must be reflected in their current practice and inevitably has to catch up with them.”

This method of criticism by veiled insinuation is objectionable and sectarian, since it really sheds no light on the truth, is he saying the League’s line and current practice are ultraleft? What does he mean when he says he doesn’t want people to crystallize too quickly over what trends these days are and are not opportunism? Does he mean the League might be opportunist based on what error we see as primary? Whatever he means, he should just say it. This method is the opposite of the “non-sectarian” debate to “bring clarity” which he makes a point of advocating in the beginning of his article. If Harding has criticisms of the League for ultraleftism, we would welcome an honest presentation of them. If the criticisms are on target, we’ll try to correct the mistakes.

But he doesn’t offer a single fact, nor does he even attempt to evaluate, or even speak to, the actual practice of the League and our predecessor organizations over more than a decade.

As for Harding’s forecast for the future, I believe that the League has established a good basis to develop and meet the challenges facing the communists in the 1980’s. We haven’t yet met these challenges, and we don’t have all the answers. But we believe the understanding, mass ties and organization we have developed puts us in a good position to begin to take them up.

The League is hopeful, too, that the challenges facing all communists in this decade can be taken up together by all the Marxist-Leninist organizations and individuals in the U.S. as much as possible and that a higher level of communist unity can be achieved through principled struggle. Many of the differences being aired right now in the debates are serious and fundamental. We should distinguish those from the relatively minor ones. If unity is to be achieved, we do have to air the serious ones, debate and discuss them. There must be a willingness to examine all views seriously, to draw conclusions on the basis of Marxist principle and the evaluation of practice, and to have an open mind.

I hope this will be the approach taken by all the organizations and individuals as the debates continue. A higher level of communist unity achieved through principled struggle can bring greater advances in the struggle of the peoples’ of the United States for peace, democracy and socialism.