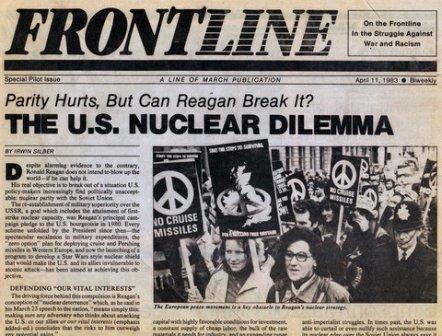

First Published: Frontline, Special Pilot Issue, April 11, 1983.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The phrase, “Fan the Flames,” is taken from the motto–“Songs to Fan the Flames of Discontent”–which used to preface the “Little Red Song book” published annually by the old Wobblies. In the mid-fifties I began writing a column of political commentary under that title in Sing Out! magazine. Years later, I resumed such commentary in the pages of the Guardian, writing a regular column which focused on controversial ideological questions before the left. “Fan the Flames” continued in the pages of the Guardian until the growing political differences I had with the Guardian staff on a whole number of questions led to its discontinuation–and the termination of my employment–in the summer of 1979.

So, as I was saying before I was so rudely interrupted....

* * *

Just as an army depends on reliable military intelligence to develop a plan of battle, so do political movements require accurate assessments of the objective conditions they face. In both cases, any tendency to underestimate the strength of the enemy or to overestimate one’s own strength can lead to disaster.

So crucial is this point to battlefield success or failure that the bearers of false military intelligence are usually shot on the political terrain of class war, similar offenders are treated much more kindly–not infrequently being accorded university degrees or, what is worse, rising to positions of authority in working class parties. And if such intelligence largely consists of glowing reports purportedly demonstrating the spontaneous militancy and political enlightenment of the masses, it is usually deemed the better part of valor to leave such estimates unchallenged.

Unfortunately, the U.S. working class has paid dearly for the fact that those who would lead it seem so addicted to such an irresponsible approach to political analysis. The U.S. communist movement has not been immune from this inclination to avoid the hard-nosed assessment of forces that the war with capital requires. All too often it has settled for that ritualistic optimism which Voltaire once aptly characterized as “a mania for maintaining that all is well when things are going badly.”

The irony in this situation, of course, is that we Marxists pride ourselves (or at least we should) on our materialism. Yet when it comes to taking a tough look at the class realities in the U.S., our movement tends to first put on its rose-colored glasses, as a result of which it frequently comes up with rose-colored assessments.

It’s not that we have an especially hard time figuring out what the bourgeoisie is up to. At the least, our starting assumption is that they’re dangerous and up to no good–a premise which manages to keep most of us on the right side of the barricades most of the time. It’s when we try to assess where the working class is at that we run into trouble.

On the theoretical level, the problem can be simply stated. Marxism holds that the working class and the capitalist class are in a fundamentally antagonistic relationship which inevitably will be resolved when the workers do the capitalists in. Nevertheless the U.S. working class–or at least a major portion of it–seems to acquiesce in, if not enthusiastically support, the very policies which the U.S. bourgeoisie deems essential to its strategic class interests.

How is this apparent paradox to be explained? Unfortunately the most common explanation of this phenomenon is simply to deny it. It’s not the workers who are supporting imperialist policy, we are told, it’s only a handful of labor “mis-leaders” who have managed to insinuate themselves into the trade union movement by various nefarious schemes. Given half a chance, the workers will always opt for progressive politics that oppose imperialist policy.

Sometimes, when the support for imperialist politics is so blatant that it cannot be denied–or when the defense of racism breaks out into open physical attacks on minority workers–the explanation is that certain workers have been temporarily tricked by bourgeois propaganda. Something’s wrong, perhaps, but it won’t last long. That this “temporary” befuddlement has dominated U.S. working class politics for more than 30 years is usually considered inadvisable to mention.

While such evasions of reality have become commonplace among virtually all brands of U.S. communists, undoubtedly the worst culprit is the Communist Party USA. Not only are the CPUSA’s glasses more rose-colored than most; as the largest and most influential organization within the U.S. communist movement, its errors have the widest impact. Particularly at the present moment, when the working class is scrambling to beat back an unrelenting assault, it is especially damaging that the CPUSA insists on acting, not as political leader of the working class, but as its advertising agency. And despite the obvious signs that the resistance to capital is sorely inadequate, the CPUSA seems wedded to putting the best possible face on everything the working class–or any section of it–says or does.

Take the 1982 elections, for instance, which produced a recession-engendered tilt away from Republican candidates. As a result, the Democrats increased their majority in the House of Representatives by approximately 25 seats, though they gained nothing in the Senate. Not surprisingly, Republicans breathed a sigh of relief when the returns were all in. Considering the length and severity of the recession–and especially the highest rate of unemployment since before World War II–the most startling thing about the 1982 elections was the limited political damage they did to the Reagan Administration.

To the CPUSA, however, “the 1982 elections were a serious setback for the forces of reaction” and refuted the view that Reagan’s election two years earlier had been “a mandate for the reactionary, racist and nuclear-confrontationist policies of the Reaganites” (Gus Hall, Political Affairs, Dec. 1982).

This intelligence is of a piece with the CPUSA’s appraisal of the 1980 elections, which ran: “The election returns show that far from a landslide for Reagan, the voters expressed a landslide against Carter and his trail of broken promises, his militarism and his anti-people economic policies.”

From this assessment, one would think that Reagan’s platform of a major boost in military expenditures, a new “get-tough” policy in foreign affairs, thinly disguised racist attacks on “welfare cheats,” and an explicit pledge to cut funding for social programs was a secret document rather than a message that filled the airwaves throughout his presidential campaign.

Contrary to the CPUSA’s wishful thinking, large numbers of workers had a pretty good idea of what Reagan stood for–and that was why they voted for him! And those votes definitely did reassure the bourgeoisie that it could proceed with a program of war preparations and attacks on the minority sectors of the working class without fearing a massive popular upheaval. (Of course, Reagan’s support was uneven across the color line, with Blacks and other minorities lending the President only a small proportion of their votes. But this only underscores the fact that the overwhelmingly white upper strata of the working class gave Reagan a substantial measure of support–much as they supported Nixon in 1972.)

Unfortunately, this is not a recent development or merely an occasional phenomenon. Much of the U.S. working class has been either actively endorsing or passively accepting as their own the politics of U.S. imperialism ever since the end of World War II.

While this may disorient those whose grasp of revolutionary politics does not go beyond the assertion that the working class is the revolutionary class in modern society, Lenin argued that such a development was inevitable in the epoch of imperialism. He pointed out that the greater concentration of capital in monopoly and its expansion on a world scale produced a scale of profits for the bourgeoisie in the imperialist countries that would make it possible for them to strike a deal with sections of the workers–and not small sections at that–for considerable periods of time. (Lenin called this arrangement “bribery,” by which he did not mean simply money passed under the table; he meant that sections of the working class enjoyed numerous privileges and a standard of living so much higher than the rest of the proletariat that they had developed a material interest in defending the status quo.)

Lenin’s conclusion from this analysis, however, was not that the working class had lost its revolutionary potential, but rather that in order to realize that potential a struggle would have to be opened up within the working class itself to expose and isolate the opportunist forces who sided with the bourgeoisie. This view outraged many of the leading socialists of the time who charged Lenin with trying to split the working class. But the point, as Lenin noted, was that the working class was already split and ”certain groups of workers have already drifted away to opportunism and the imperialist bourgeoisie.”

The relevance of this brief excursion into communist history is apparent. The hold that anticommunist, pro-war, national chauvinist and racist politics have on large sections of the U.S. working class is of a scale that thoroughly overshadows the opportunism of sections of the labor movement in Lenin’s time. This opportunism has a stubborn material base rooted in the hegemonic role of the U.S. within the world imperialist system. Therefore it will not be broken without a most determined struggle that must be led by the most conscious forces in the workers’ movement.

Which brings us back to our differences with the CPUSA. The point is, the CPUSA’s rose-colored assessment of the political consciousness and activity of the U.S. workers is not simply a momentary misreading of events. Rather, it is a fundamental political error, rooted in the mistaken notion that the U.S. working class is basically homogeneous and that it can be smoothly united without a protracted and bitter fight against opportunism within its own ranks. Lenin dubbed such romantic sentiments “official optimism,” and argued, “We must have no illusions about ’optimism’ of this kind. It is optimism in respect of opportunism; it is optimism which serves to conceal opportunism.”

Breaking with “official optimism” of this variety is an absolute necessity if U.S. communists are to gain reliable intelligence about the actual balance of forces in the class struggle, and take up the arduous task of identifying and leading the struggle against opportunism.

Will such an undertaking split the working class? To the-extent that the U.S. working class is already under the ideological hegemony of opportunism, yes it will split the class; and a good thing that will be. For until the U.S. working class splits away from opportunism–and in particular from its concentrated expressions in racism and national chauvinism–it can never attain the revolutionary unity it requires to hold up its front in the fight against imperialism.