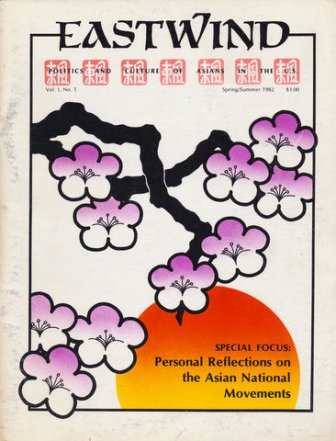

First Published: EastWind, Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring-Summer 1982.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

What motivates people to dedicate their lives to organizing Asian people? Seven activists with interesting and varied backgrounds in the student movement, community organizing, labor work and the arts share some of their thoughts on this topic in the following essays. They tell us a little about their lives, why they became involved, and, share some lessons from their experiences.

Leading off the essays is Philip Vera Cruz. Now living in retirement in Bakersfield, California, Philip Vera Cruz has been organizing Pilipino farm workers in Central California since the late 1940’s. He later served as Vice-President of the United Farm Workers Union.

Lillian Nakano, a prominent activist in the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations and a member of the Little Tokyo People’s Rights Organization in Los Angeles, offers her perspective on the Japanese American movement. She describes the long trek from life after the camps to her current political involvement.

Happy Lim has been organizing in the Chinese community since the 1930’s. Lim, who is 72 years old, is still working and actively supports the progressive movement in San Francisco Chinatown. A frequent contributor to UNITY newspaper, Lim is a well-known poet and essayist.

Lori Leong is a member of the League of Revolutionary Struggle (M-L) and has been organizing in New York Chinatown since 1969. She is an active member of the Progressive Chinatown People’s Association, a community organization, and is participating in the campaign against the gentrification of Chinatown.

May Chen has been active in the Asian American movement and the Chinese community for many years. She has been a teacher and community organizer. She currently works for the Chinese Committee of Local 6 (the Hotel, Restaurant, Club Employees and Bartenders Union) in New York City. She describes some of the lessons she learned while participating in the struggle to build a child care center in Los Angeles Chinatown.

Alan Nishio is the President of the Little Tokyo People’s Rights Organization in Los Angeles. A longtime activist in the Asian and Japanese American movements, Alan’s experiences have spanned student activism, working for ethnic studies and Third World student admissions, and community organizing.

Wes Senzaki, one of the founding members of the Japantown Art and Media (JAM) workshop in San Francisco, describes his development as an artist and examines what it means to be a political artist.

We hope these essays convey the optimism, dedication and determination that are an intrinsic part of the Asian and Pacific national movements.

I wanted to go to college but my family did not have the money. To accomplish my goal, I had two alternatives, I could come to the United States or I could stay in the Philippines and teach in Mindanao where I could earn some money to go to college. I took the alternative of coming here. They taught us in school about the many opportunities in the U.S. and of equality in the U.S. All that kind of talk gives you hope.

My parents had a little bit of land. My father was sickly and could not take care of the land so I was gradually selling it. The money from the very last part of the property was what I used (to come to America). It was not enough either. I borrowed some money from relatives. Then I paid my fare to get to Seattle. When I finally got to Seattle, I had only $25.00 left.

There were four of us who came to Seattle in 1926. When I was leaving our hotel, I met my friend from high school. He said, “You know, we were talking about you last night.” I asked, “Who?” He replied, “Your uncles. They are in Spokane, working at the lumber mill. You can find a job there.” So we left and I got a job at the box factory. They were paying 25 cents an hour for ten hours. They shifted me to the night shift but then we were laid off. Then the Pilipinos went on strike. That was my first experience to see a strike but I didn’t know what they were talking about.

Then I started to work in a cafeteria. My mind was still on school. I was a busboy. I mopped the floor and swept the sidewalk. I made $14 (a week). When the Depression came, I made $5 a week, six days a week, ten hours a day. I would go to school when I could.

Times were getting harder. I saw an ad. They said they would pay transportation to go thin sugar beets in North Dakota, so I tried. I only made $35 and could not get back to Spokane, so I went on to Chicago. I was a busboy again.

In 1928, I received a letter from home. My father had died. I thought about school again so I went back to Washington, worked in a restaurant and was able to graduate from high school in 1932. I was bothered about my brother and sister. I needed to send them money. I heard from my mother. Someone wrote for her because she could not write. She said that my sister stopped going to school because she could not afford it. But my brother was still going to school. He was in the fourth grade, so I kept on sending $25 a month. And this meant that I could not go to school.

Then I went to work at a country club. I got to play the game. The people in high places, although they do not like you, they want you to serve them. When they called me, I’d run to make them happy. They think I’m doing my job because if you antagonize them, then you lose your job. You got to play the game. You can’t say the hell with you, or you got nothing to eat.

So I found out that what they told me about the U.S. were half-truths. They didn’t tell me of the handicaps which are inherent to me because I’m not white. So their equality was a fake. I found myself in a situation where I was a scapegoat. I could not get out even if I tried. I didn’t have the means and society didn’t accept me. What happened to me happened to other Pilipinos, Chinese and Japanese.

I found two kinds of life in the U.S.: the well-off and the enslaved ones. I found that there were so many reasons why I belonged to the enslaved side. I compared myself with the others (whites) to see what was going on. You see how they live, and how you live; what opportunities they had and what you did not receive. They hated us, but they could not exclude us because of our political status. The Philippines was under the rule of the United States. [ed. note: As a commonwealth of the U.S., the Philippines technically had free emigration to the U.S.) But we were still not eligible for citizenship. They could not make a law to exclude us like they did to the Chinese and Japanese, but they did something that amounted to exclusion by putting a quota of 50 people per year to come into the country.

So my hope did not materialize like I thought. The promises of opportunities and jobs did not come. What was this American dream?

My new dream formed, that equality and freedom should belong to all. You cannot be free to step on somebody’s toes. Not everybody will make the “American dream” of being millionaires. Our dream must become the sharing of opportunities and benefits of freedom for all. I think that whatever nationality you are, you should be treated equally, otherwise you don’t have equality.

During World War II, I got drafted and went into the army. When I got released from the army, I was supposed to get a job in Vallejo at the shipyard. They said we could have one month to visit relatives, so I went to Delano to visit my relatives. I was also thinking that I could work there. So I tried, but it was hard because I was not really used to working on the farm. One time when I was weeding cantaloupe, the ground was hard and it was so hot, I hurt my back. I couldn’t straighten it. So I stayed until my back got stronger. I decided that I didn’t want to live in the city any more.

I could not be concerned just about myself or my family but also of the people who are like me. That’s why I got involved. It was the union that really brought me about. If you are alone, what can you do? When you build unity, you cannot build unity without others. You can’t just think about yourself. You’ll be too weak. You’re not big enough to carry the load; you need everybody.

The unions were coming to the fields. In Stockton in 1948, we were supposed to cut asparagus but all the Pilipinos went on strike. Again in 1950, when we worked in the vineyards, the union came again – the National Farm Workers Association led by Harry S. Mitchum. We tried to form a local in Delano but there was not yet so much support for the union. Later, the Pilipinos formed a union – the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC). They were the ones that initiated the grape strike. Cesar Chavez was organizing Chicano/Mexicano workers. Later our two unions merged to form the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, taking part of the name of the union Chavez was organizing and taking “organizing committee” from the AWOC.

Despite my disappointments, I’m optimistic. The union is the only way. Without that, you got no power. You can have power if you get together. But, of course, you got to start as Pilipinos. Organize yourselves. Then get together with other groups. The Pilipinos need organization and unity. You need to know your principles so that when you get together with other groups, you are not left out and can build stronger unity.

My husband and I joined the Little Tokyo People’s Rights Organization (LTPRO) quite by chance. Our son came home from college one summer and got us involved in the redevelopment/housing struggle in Little Tokyo. Though we were openly supportive, it took some urging on his part to pry us from our apathy and cynicism. The transition from practically a lifetime of non-involvement, non-confrontational lifestyle, coupled with a deep sense of inadequacy and apathy developed over the years since the camps, was highly disconcerting to me. I felt some ambivalence in the initial phase of my involvement. There I was, an average, quiet 49-year-old Sansei woman, never before involved in any community work, much less from a political perspective, amidst all the young activists in the community. This struck me as being so incongruous.

Through my involvement, I came to know “J-Town” beyond its glitter of touristy shops and restaurants. As I walked by the old shops and hotels where our Issei had lived and toiled decades ago, I felt proud to be part of this community. It seemed right to join LTPRO, an organization which was fighting so hard to preserve that heritage.

At the same time, it made me reflect on my own past and how the deprivation and alienation caused by the dispersal of Japanese Americans after the camps had affected us all these years. By re-examining the past, all that was in the “Nisei experience” – oppression, fear, alienation, the question “to-assimilate-or-not,” and Gaman (to accept and endure) – which was forever suppressed came back out of the mire. Slowly the jumbled pieces of the puzzle began to fall into place one by one. What I share is only a small facet out of 110,000 Japanese American lives which were inexorably altered in that one instant – Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941.

My father was arrested by the FBI on December 7, 1941. One year later, on Christmas Day, we were reunited and boarded a ship bound for San Francisco. Destination: Jerome, Arkansas, Concentration Camp, USA.

I was born in Hawai’i, raised in a middle class Japanese fashion by Nisei parents with five children. Childhood was all carefree innocence and boisterous fun. Having shown a knack for music at an early age, my parents put me to the shamisen when I was eight. Music was a great part of my growing up until the war. Suddenly after Pearl Harbor, my Japanese instrument among all the other paraphernalia were hidden from sight for the duration.

We were abruptly taken from our home to the camps. I was 14 years old. Being herded off at gun point, three mindless years behind barbed wire fences and cut off from mainstream society all had to have deep negative impact on our lives for years to come. Today, my sister still says, “As kids, we were so robust and uninhibited. It seems everything went wrong since the camps.” When the camps closed, we moved on to Minnesota, back to Hawai’i, and finally to Chicago.

All adults leaving the camps were given an insulting orientation which to my mind was also an “admission of guilt” forced upon us. We were to avoid large groups of Japanese, avoid use of our language, to develop “American habits” to become accepted, to conform to the norms of the outside world and, finally, to behave in a manner reflecting all that is “good, reliable and honest in Japanese Americans.” We were fresh out of the camps, burdened with this “parolee” mentality and left high and dry in the face of out-and-out racist hostility and exploitation.

At 17 and ill-prepared for the adjustment, I was bound for some real problems in coping. But mine somehow seems so minuscule now when compared to the situation of those a few years older who already had children to raise and jobs to establish.

My brother had moved out to Chicago ahead of us and found a job at a huge wholesale bakery. On the very next day, he was fired and run out of the company by a hostile management and union, and even today, he will not buy that particular national brand of bread. Thus when my parents first started out with a small restaurant to keep the family going, I was only too glad to stay “close to home.” In the coming years, we always went through Japanese American employment agencies rather than to face job hunting on our own, for the ordeal of humiliation and demoralization hardly made it worth the effort. Those who hired you expected 200% effort, for ”to prove our worth” was the by-word.

Manifestations of racism came out in different ways. One such incident simply started with my asking for a transfer to another department which lead me right to the manager’s office instead. He proceeded to berate me in a manner so demeaning that I’ll never forget it. The gist of it was that I should have been overcome with gratitude that they hired “our people” and to begin with, affording us the luxury of a nice modern office with a reputable firm. To add insult to injury, he offered me a piece of “good advice” before suspending me and that was to say “be grateful.” What stuck in my mind was the fact that at such an opportune moment, I was struck absolutely speechless and I despised myself and the lot of a “Jap” all at once.

Apartment hunting too was a hateful task. The expression varied from that of sheer disbelief that we “Japs” would have the gall to approach them to one of fright as in encountering someone totally alien. There was the usual smug pronouncement that the apartment was no longer available while the vacancy sign stared blankly at you for weeks after. Or a small town restaurant that had a sign in the window, “NO JAPS ALLOWED.” I was stared at out of open hostility and plain curiosity and cursed at.

These thousand and one incidents had a most insidious effect of gradually chipping away what self-worth and pride you managed to retain. Even worse was when you begin to believe that you must indeed be inferior.

In the midst of this, I was married at 21, and suffice it to say, it only complicated matters. In a sense, this was the catalyst that began the process of changes I was to undergo. Like Ibsen’s Nora, part of it was a personal rebelling of sorts against the old order of things. That aside, an array of emotions – mainly frustration stemming from this racist environment – merged into our relationship and as such brought on the inevitable tumult. Despite it all, we both recognized it to be an intrinsic part of the whole “learning” process and strived to maintain a relationship as long as we seemed to be growing and moving in the same general direction.

I had begun teaching shamisen after vacillating between that and art school. At 27 our son was born, and I enjoyed the pleasures and pain of parenthood. Soon after, I began teaching again, which entailed recitals and other performances in addition to classes. As a mother, feelings of remorse around my split devotion brought on a new series of guilt feelings. Around this time, we were very much into Zen Buddhism for several years, but we then came to realize that what we sought was not within the realm of religion. Other distractions in the way of sports, plays, concerts were pleasantries we shared in, but a sense of truly “relating” to things as Asians was always the missing link and seemed almost a lost cause. Perhaps a final “grabbing at straws” attempt was the basis for our packing up and moving to Japan. We lived in Tokyo and Yokohama for six months as “expatriates” of sorts, but as Japanese Americans we felt we were foreigners there. After our return and move to Los Angeles and over the years, we settled down in a lifestyle quite mundane and peaceful as we came to accept things as they were.

Today, our lifestyle again has gone through drastic changes. Appropriately for us, this was the final but crucial step which was so necessary to make a breakthrough in what seemed a lifetime of futility. As issues upon issues filled the void endlessly, this path continues to illuminate a relevant part of our life.

Nor do I think I am alone. The redress/reparations issue, which hit at the heart of every Japanese American in the nation, began to cause a rumble in our communities, and long suppressed anger and bitterness were finally articulated by all – Issei, Nisei, Sansei and Yonsei alike. Hundreds of Nikkei testified at the hearings and organized around the demand for reparations. This was truly a turning point in the history of Japanese Americans, a beginning of a movement encompassing every generation and all sectors of our community! The Nisei are involved now. We are not only sharing our past camp experiences, we are supporting and spurring each other on to fight for what we feel is right and just! Could this be the time for all to dispel the enigma of the “quiet Nisei” – a time when Sansei need no longer treat us with deference or awe, a time to bridge the generation gap and fight together as one strong community for redress/reparations as well as other issues? The answer is coming through action. This year at the Day of Remembrance commemoration in Los Angeles, 300 people of three generations of Japanese Americans marched together through Little Tokyo chanting, “Justice Now, Reparations Now!”

I feel overcome with pride and strength in the realization that we Nisei are coming out of the camps at last – no longer fighting “one’s own battle” in isolation, but looking to each other for support and together building a vision. There is a resurgence of Japanese American pride and a fighting spirit. It means that we are concerned about the things that are happening around us and that we intend to act upon it. It means that we are inspired by the “young people” and that we in turn must inspire them too! As I join in the fight, drawing from and sharing in our strength, organized and unafraid, I feel liberated at last. Above all, there is now a clear purpose in my life – a striving towards a vision of a society in which we, our children and our future generations can fully realize what it means to live with pride, dignity, equality and self-determination.

The U.S. society of the ’30s was one of economic depression. Confronted by this hard fact and living in a grey social atmosphere, struggling to make a livelihood, I became tempered. Some of my childish dreams were shattered, but a vision of the future lent an incandescence to the era.

The Chinese community of the ’30s was one full of economic oppression. It was a hard time to find a job and it was a time of racial discrimination. Many of the scenes of that time still stir up strong feelings within me. My strongest impression is one of many people out of work and little shops unable to survive.

Even for myself who was single, I did not know where I would stand from one day to the next. It was this kind of hardship that threw me into struggle and led me to follow a revolutionary path.

Under these conditions, many progressive-thinking young people stood up to the call of the times and became staunch fighters for the betterment of society, although there were also those who were confused and unclear. And there were even a few who strived to step on top of others for their own gain and oppose the great tide of social transformation.

Those revolutionary-minded youths who were advanced in thinking had an unshakeable determination and faith. They provided a solution to transform the social services of the Chinese community, to fight against poverty, and to answer “the problem of starvation.”

These were the youths who established a new and broad ideal. During these times, they worked with others in the labor sector to organize the “Afterwork Club” which staged frequent propaganda forums on the street corners to educate people about exploitation, oppression and the unemployment suffered by workers. They even organized demonstrations and petitioned to the Chinese Six Companies demanding unemployment assistance. Even though they were unable to get definitive results, they did reflect the basic demands and aspirations of the masses.

The corrupt society brought about those who would rebel against it. Thus, the birth of the California Chinese Workers Mutual Aid Association was like a clarion call in the darkness. It was the summer of 1937. A group of fishshop workers returning to San Francisco from far away Alaska discussed how to organize a Mutual Aid Association. Life up North was so extreme that after a few months’ seasonal work, Chinese workers felt their lives were without purpose.

Without being united, the Chinese workers would never be able to improve our livelihood and fight for rightful treatment. So when we got back to San Francisco, several of us Chinese workers resolved to form the Chinese Workers Mutual Aid Association, which was founded on October 9, 1937, at a storefront at 1038 Stockton Street, and later moved to 947 Stockton Street.

From the very beginning, the Chinese Workers Mutual Aid Association called for the unity of workers. Many workers from the restaurants, laundries, sewing trades, farms, seafaring workers and longshoremen joined. It became a workers mass organization. With this collective power, it started to engage in propaganda and education for Chinese workers.

The Association, at the same time, kept close connections with the mainstream of the U.S. labor movement, through groups such as the International Dock Workers Union, the Seafarers Union and the Dishwashers Union.

The Association assisted workers of all trades to get organized. It can be said that the Association was in the forefront of bringing the Chinese workers into the labor unions.

Because it met the needs of the times, it rapidly expanded its membership to over 600 within two years.

The Association held regular sessions to teach Chinese workers about the new world view and to help them to establish the necessary ideology for the modern-day working class.

There were many educational activities like English class, Mandarin classes and singing classes for workers to learn songs of revolution and about the War of Resistance. Most importantly, there was the Workers Movement Study Group, where people with experience in labor organizing strategies and general basic knowledge talked to the workers.

The Association published the “Cooperative Pamphlet” from the very beginning. It was a quarterly, which, other than reports of the organization’s work and the labor movement, had political viewpoints and analysis on the current situation as well as cultural pieces.

In 1938, Mao Tse-tung published the reknowned article “On Protracted War” which greatly armed the thinking of the broad masses in China and later led to the historic victories of the Resistance War and the War of Liberation. It also helped progressive people overseas by deepening the understanding of the significance and strength of ideological work and pointed out that only if we persist in struggle will we overcome any weaknesses and achieve final victory.

Looking back, the path we treaded was an extremely difficult one. As for the future, I feel that the tasks we are facing are tremendous. We have to unite more people and raise our ideological level. Based on my experience as a revolutionary, I believe that this is what we have to center our work around.

Comparing the conditions of the ’30s to today, I feel that the situation now is better than before. With the reactionaries weaker and the inspiration of new China, more and more progressive youths are springing up, although there are still some people who cannot rid themselves of the need for self-indulgence and thus cannot depart from the realm of being above the masses.

Only if we take reality as it is, do mass work, persist in the correct line and struggle relentlessly will a free, just and equal society become a reality. I will follow the advanced youths of today and keep on fighting.

I got involved in the late ’60s and early ’70s when I was a freshman in college.

What affected my involvement in the Asian Movement was being in a relationship with an Asian guy who was active on campus. But I was an oppressed woman in that relationship. I went to meetings with him, but I did not feel I could participate. He didn’t encourage me to express my ideas nor did he seek them out. Then I met other Asian sisters in the Movement, and they really helped me express my ideas for the first time in my life. I could actually feel that I had some ideas to contribute to building something. But at the same time that I began to express my ideas, I had a very difficult time with my boyfriend. He resented my participation and closeness with other Asian sisters.

For a long time, I subjected myself to a lot of physical beatings by him. Looking back on it from where I’m at now it’s hard to see why I would subject myself to that kind of treatment by a man. Like a lot of other women, I was brought up to accept your place in society – to get married, listen to your husband, basically get a man and hold on to him. Getting the courage to break out of that kind of relationship didn’t happen overnight. It only happened when I began to understand what was going on, and with the support of people around me, particularly Asian women.

I had led a pretty sheltered life. My father was a restaurant worker, and my mother worked in garment factories. I was a shy person not really feeling or knowing that I had to deal with the world situation.

At that time, the Viet Nam War was a very big issue, and whether you wanted to or not, you were affected by it in one form or another.

I began to work with a group of students at Columbia University. I had come in touch with people from Triple A (ed note: Asian Americans for Action) who were pretty active in the Viet Nam War issue as well as with other students from a couple of campuses around the city. We talked about how we felt as Chinese people as well as the discrimination and problems of Chinese people in this country, and we began to think about doing work among the poorest sectors of Chinese. And looking at it realistically, the people who suffer the most are working people, people who are in the Chinatown community, people who are garment workers, restaurant workers. They suffer extreme problems of basic living from jobs to education. So even though we were students on campus, we felt it was very important for us to go out into the Chinese community and begin to work down there. So we went to Chinatown one summer as a collective and began to work particularly among youth.

The rise of the Black Panther Party had a very big influence on my own understanding of what we should do. The Panthers pointed a certain direction which was basically that the system in this country perpetuates and controls the lives of the people in the communities. They took up work in their community through Serve-the-People programs and actually tried to organize people to fight the government. I think this really helped me see that we should also take this up in a very serious way.

At that time, I was also influenced by the situation in China. I saw how a country like China where my parents came from was able to really change something. Socialist China was actually beginning to deal with the problems of the Chinese people. It gave me tremendous inspiration. If they could do it, then we could certainly do it in the U.S. no matter how long it takes.

I Wor Kuen (IWK), a revolutionary organization, was formed in that year, 1969. It formed from the collective that went to the community during the summer and winter of 1969. We also began to put out a newspaper called Getting Together.

We took the paper out at 6 or 7 o’clock in the morning and tried to sell it to high school students, and we sold it on the streets of Chinatown. There was a very, very big response to it, and I think this was very encouraging for us. It confirmed our belief that what we were doing was right.

It was only through revolution, the basic changing of this whole system, that we could really solve the problems of our people, because basically this system does not want to help poor people. That was our ideology, and we would take it with us into the work we did in the next period of time in Chinatown.

One of the biggest issues that we got involved in was the struggle around the Bell Telephone Company which was trying to evict and basically closedown and drive out a couple thousand tenants from their homes in order to build a switching station. What came out of it was a very big organization of tenants called the We Won’t Move Committee. Basically we united not only Chinese but also a lot of Italians in the area. Eventually, Bell Telephone had to drop the plan and move out of Chinatown.

Another issue we were trying to address at the time was health care in the community, because there was a very serious health problem, the illness of tuberculosis. We felt that it was important for us working in the community as revolutionaries to understand that we can’t just talk about a long-term solution and just wait until it happens. It happens through a long, hard process. Part of the process is to fight for a way to improve people’s lives now. So we took up a campaign to do TB testing. We went out in the streets of Chinatown every weekend and gave free TB tests.

Some of the other work we did was to show movies every weekend, including films from China. Even though the KMT had a lot more control at that time, people would come to our office and sit through those movies knowing that the KMT would try to intimidate us. We also participated actively in coalitions existing in the Asian movement at the time. We did work among Asian women, students and other sectors. For example, we participated in the Asian Coalition, formed to bring Asians together to take a stand and unite to stop the war.

Looking back, I would have to say that there have been a lot of changes and development in the last 12 years in the Chinatown community. The most noticeable change is that the problems of working people have gotten worse.

In the last few years, we have seen the rise of the New York struggle of Chinese restaurant workers for unions. Conditions such as 15-hour work days, 6-day week, no sick pay, no benefits are being challenged by the workers. Uncle Tai’s was the first Chinese restaurant in New York to unionize ever – basically the first in the country. The workers stood up and said, “We’re not going to take this any more” and went on strike. They wanted a union. They wanted a basic minimum wage and to be given humane conditions to work under.

After Uncle Tai’s was able to gain success, it snowballed. So presently in New York City you have up to 10 restaurants, which are unionized into the American hotel/motel restaurant union, and this struggle has had a large impact.

A lot of the restaurants that did unionize were outside of Chinatown, but it doesn’t matter whether you are inside or outside of Chinatown. You’re Chinese people with the same working conditions, and that had a big impact on the situation for workers inside of Chinatown.

In 1979, the Silver Palace workers in Chinatown went out over the issue of tips and basically pulled a walk-out and fought real hard in a mass way, taking it out onto the street and calling for community support. They were able to get rehired. This is an issue which is a burning issue for the Chinese community now, and I think it is a very important one in the future struggle, for the livelihood of Chinese people.

I have been involved in these and other struggles through my work in the Progressive Chinatown People’s Association (PCPA) which is a mass community organization of Chinese workers, students and other progressive Chinese. We formed PCPA in 1977 – people from IWK, community workers, residents, Lo Wah Que and students – to fight in an organized way for the rights of Chinese people.

Another issue which PCPA has been actively involved in is housing. Chinatown sits next to the financial district which is Wall Street, the largest financial center in the whole world. Chinatown is basically six-story buildings which are totally unprofitable for builders in the city.

Right now, there’s a big movement in New York City overall to target certain communities to “gentrify” the community. What that means is to basically allow land developers to go into certain poor communities, develop for profit and bring back capital to the city. Last year, the city was able to secretly pass the Special Manhattan Bridge District (SMBD) plan which basically sectioned off a whole piece of Chinatown for land speculation and to give incentives to large developers to build high-rise condominiums.

This is a very important struggle because the whole question of these speculators coming to disperse Chinatown is one way to break the fighting ability and organizing potential of the Chinese National Movement. The community and its future should be controlled by Chinese people.

The sentiment to oppose gentrification is there – in the struggle of the tenants all around the SMBD, Henry Street, Market Street and Madison Street. This is capsulized in the struggle at 109 Madison Street where we are fighting the largest land developer in the whole of New York State, Helmsly Spears Corp., which is going to build a multi-million dollar condominium in the middle of Chinatown.

I think the mass movement of tenants and tenants’ associations is a very important step in the fight. The issue also has a broader impact. How will the community as a whole be affected if the tenants and working people are driven out? The soaring rents caused by land speculation will drive Chinese businesses and grocery stores to bankruptcy.

The fight against gentrification is going to take a very big effort, not only among the tenants themselves, but I think it’s going to take a very broad united effort of the different sectors of the Chinese community. The different agencies that do a lot of community work, the businesses and family associations need to sit down and say, “Wait a second, what is going to happen to Chinatown? With this move, what does this mean for all of us who have different interests?”

In one sense, the Chinese businesses, restaurant owners, for instance, have slightly different interests from Chinese working people, but there is also a common interest when you see the government moving in to destroy the community. Then, the primary question becomes, “What are we going to do? Are we going to take this on in a united front kind of way, deal with this and see how to stop this dispersal?”

I think one thing I have learned working in Chinatown for the past 12 years is that it is not easy. It’s not something that happens overnight, and when there is a success, and there have been numerous ones of them, it sets the conditions for what is possible in the future.

The housing struggles at 54-56 Henry Street, 22 Catherine Street and 109 Madison Street have been successful. And that success comes from what went on 12 years ago with the Bell Telephone struggle.

One of the key questions is how to work toward building some kind of unity among two people, two organizations or among 10 or 20 organizations. We put on a health fair ten years ago. It took a united effort of over 20-25 organizations and that wasn’t easy. It was a very good feeling that we could put something on like that. In the process of ten years it has not been easy to pull those things off again, but we have to be able to learn from this.

You have to start from what is the best way to help the situation; what is going to make the best gains for whatever you are fighting for. It may not be just your way. It may be a combination of people sitting in a room thinking about what is best. It is important to listen and learn from each other to find the best way to solve a problem. That’s what has helped the movement in Chinatown to grow as long as I have been involved.

The questions now facing the Chinese community are massive. There’s been a huge influx of immigrants from Southeast Asia and Asia. There’s a large population, yet needed services are being cut and people are losing their jobs. I think in this period of time there has been a resurgence of the desire for unity in Chinatown, of people seeing that we just can’t sit in our little holes feeling comfortable with ourselves.

There’s got to be a way to build the movement so we can fight together as Chinese people and as Asians in New York to deal with problems. I think there is a natural feeling of Chinese people wanting to band together to fight. It’s there. The potential is there. It’s a ripe situation.

I am an East Coast Chinese American born, raised, and educated in the suburbs of Boston, Massachusetts. I have been living and working in New York City for two and one-half years. However, I had the invaluable and unforgettable experience of living for almost a decade (1970-1979) in Los Angeles, California – being part of a dynamic Asian movement, attending graduate school at UCLA, working in the Chinese community, marrying another East Coast Chinese American and having two babies before moving to New York.

Culturally, socially and politically I am a product of the 1960’s, a ’60s person – as we are coming to be called – who attended high school and college during that turbulent decade and became politicized by the massive, anti-war, civil rights, student and women’s movements of those times. In ’60s lingo there was a slogan, “If you’re not part of the solution, then you’re part of the problem.” Broad consciousness was developed about fundamental problems of the system of U.S. capitalism, of the need for every person to be involved in solving these problems. People who did not or would not get involved were “copping out” or just wanted to work “in the system” – actions which ran against the social and political currents of those times. I first got involved because I was young and everyone was involved in marching, petitioning, teaching and soul searching.

I was among 3,000 students in the college football stadium holding a mass meeting to vote about going on strike, closing down the whole school in support of students killed by the National Guard at Kent State . . . Black armbands, and red fisted strike symbols filled my graduation from college in 1970!

It was during this time that I first met and worked together with “political” Asians. In fact, it was during this time that I related to fellow Asians more broadly and deeply than ever before. Socially, I stepped beyond the CSA (Chinese Student Association) “mixer” into more liberated and equal relationships with Asian men as well as lasting friendships and solidarity with Asian women. Culturally, I was sharing and part of building a new perspective on Asian experiences in the U.S. which integrated the cultures of Asia and America. Every struggle and issue in the Asian Movement gave me new and deeper opportunities for meeting and working with Asian people of different backgrounds and situations.

The fight to build and stabilize the Little Friends Childcare Center in Los Angeles left a lasting impact on me. It started as a weekly playgroup of young and married Chinese American women and immigrant mothers and children. We shared common aims of providing a service to liberate women from the sole, solitary task of housekeeping and childrearing, to socialize and educate our children in Asian cultural traditions with non-sexist, non-racist values. When I first worked with the Little Friends Playgroup, I was an intellectual, middle class, single Asian woman and approached the project with the perspective of college idealism, feminism, and a touch of a missionary attitude. I was studying to become a public school teacher. Marriage and children were completely outside of my immediate plans and imagination. At 23 or 24 years old who wanted to be “tied down.” Women in such straits had to be “saved.” Also, I was convinced that young Asian boys absolutely had to be educated in a non-sexist curriculum so they wouldn’t make such backward husbands as their fathers who left all the chores of housekeeping to the women! Such was my mentality in those days. The Chinese immigrant mothers who joined Playgroup with their pre-school children taught me more than words can describe and deeply changed my perspective and relationship to the Chinese community. These women were not ’60s people but they shared a sense of sisterhood and conviction about women’s equality and the Chinese community that paralleled ours. Though not much older than me, they shouldered a lot more “real world” responsibilities and pressures than I did and on top of this, they made time in their busy schedule to help fight for child care and other community needs. In a very concrete, personal way, they showed me a completely new model of women who worked, related to husbands, and raised a family – women who had a lot of independence and personal integrity but weren’t striving for a career or self-fulfillment in an individual sense. Instead, their background reflected struggle, survival, and step-by-step progress contingent upon the collective experience and advancement of their families and people’s status in the U.S. In other words, they wouldn’t advance unless everyone else in their situation did and progress did not mean being “saved” by idealist college students. It made me realize that in order to truly fight for Chinese people’s rights, I could no longer see myself as separate from the overall community, as “exceptional” or some kind of trained technician operating above the working people and immigrants.

Through knowing, understanding, working together with the people at Little Friends, I got an education in how struggles and politics occur in “real life.” As we developed the Little Friends Playgroup into a fulltime day care service for working mothers, we confronted a hostile city government issuing orders to close us down because we lacked a “licensable facility.” Though very diverse, our group was strongly united and we fought over several years to defend and stabilize our small program. With thousands of working women in Los Angeles Chinatown, the available child care services were pitifully few. We told the City, “Child care is our right!” And the government officials responded, “Child care is the mother’s responsibility.” Or even worse, “If you Orientals can’t take care of them, why do you have so many!” It was a real version of the “Yellow Peril” mentality with a sexist slant and it taught me a lot about where government officials were coming from. I revisited Los Angeles in 1981 and went to see Little Friends in a bright, renovated building with some of the original mothers still involved in teaching or advising the group.

Leaving the people and struggles in the Asian Movement in Los Angeles was very hard but with two small children very close in age, we began to miss families and relatives back East. So we relocated to New York closer to parents and grandparents and are still deeply involved with Asian communities and people.

A lot of people think the Asian Movement is centered exclusively in California or the West Coast. Yet in many ways, New York City is a pace setter for political struggles including many aspects of the Chinese American movement. Life and work in New York has been intense for us, especially compared to the relatively mellow pace of Los Angeles.

I remember about a whole year of East/West Coast culture shock when I moved to Los Angeles. Where were the people and the street life? What happened to the seasons – the hot, humid summers and the blustery blizzards of winter? Even the language in California was different – slower, simpler and sprinkled with strange idioms which people used seriously, like “off the wall” and “far out.” But it was wonderful to see so many Asians in all parts of the city doing all types of things. I loved Hermosa Beach, Holiday Bowl, a rock band called Hiroshima with Atomic Nancy, and fast food stands where you could buy a teriyaki burger. You could buy packaged tofu at Ralph’s and Safeway, the big supermarket chains there.

Moving back to the East Coast I was feeling the same cultural shock but in reverse. The regional differences between California and the East have an enormous impact on Asians in each area. The sheer pace and population density of New York makes people constantly hustle and struggle, sometimes together and sometimes against each other. The street life and relationships among people are intense and exciting. And the potential for people coming together, organizing around any kind of issue exists right in the streets. New York is a very literate and cultured city – people read a lot even in the subways. There are hundreds of small theaters and art centers. New York’s Chinatown has more Chinese language daily newspapers per capita than anywhere else. And there are dozens of Asian bands, martial arts, operatic and musical ensembles in the city. These conditions make Asians and the Asian Movement in New York City sophisticated and lively. Yet in contrast to the density and street life in New York Chinatown, many Asians in the East Coast, especially Asian Americans, are dispersed, isolated and alienated from Asian culture and community. Asians are perceived by others to be scattered individuals rather than a cohesive ethnic population. We are not recognized as a disadvantaged minority group in most East Coast institutions and even Third World groupings often overlook Asians. Stereotypes and myths ranging from “success story” to Charlie Chan are rampant and the Asians in these situations are forced to assimilate or to feel stifled or frustrated because they have never known any values other than East Coast status consciousness, competitiveness, paranoia and provincialism.

For this reason Asian organizations on campus and in the communities serve as a focal point for our dispersed population. More and more, New York Chinatown remains and grows as a center for Asian American groups as well as for Chinese immigrants. There is a strong sense of nationalism in the Asian Movement in New York which brings together people of many backgrounds around common issues. I love the discipline, character, and drive of Asians on the East Coast. It is exciting and challenging to live and work here, to revive and realize the training and cultural inclinations of my youth. Yet, I dearly appreciate the sense of experimentation and tolerance I learned in mellow Los Angeles. I like to look at the Chinese movement as national in scope, drawing the best from the experience and lessons of each specific area. It’s also important to look at today in the context of Asian American history – some recent history (’60s and such) back to the old days. Some young students today look at people like myself as something of a living historical relic. Now that I’ve written so many papers I almost feel like one. I don’t think I’m very unique but my experiences are part of our people’s experiences. To know and understand me is to learn about one small part of the dynamic and progressive trend among Asian people – sharing experiences, uniting together, standing up and speaking up for dignity, political power and equality.

I was born in an American-style concentration camp called Manzanar on August 9, 1945 – the day the U.S. government decided to drop an atomic bomb on Nagasaki, Japan. The concentration camps and the A-Bomb – two acts of genocide against people of color rationalized under the guise of “national security.” The circumstances and timing of my birth have since caused me to do a great deal of reflecting on what it means to be a Japanese American.

Like other Nikkei (persons of Japanese ancestry), the concentration camp experience had a significant impact upon my life and identity. Prior to the imprisonment of my family, my parents owned a small grocery store. The store was purchased after years of saving enough money to make a down payment. The store was doing well until Executive Order 9066 was issued on February 19, 1942.

When E.O. 9066 was issued, all was lost. With the expulsion from our home, our family was forced to sell the store and other goods at a tremendous loss. Other valued personal possessions that were not sold were stored at a neighbor’s house. This property was later all stolen while we were in camp. What money that was available was spent to help other relatives or was spent while in camp in order to provide for the daily needs of the family.

The camp experience made my father a bitter man. We left Manzanar after three and one-half years of imprisonment with little with which to start a new life. With the pressures of supporting a family, my father was forced to take up gardening. My father hated gardening, but his pride would not allow him to consider a job where he had to work for the people who had imprisoned him. Besides, he considered gardening only a temporary occupation until he was able to save up enough money to buy another store.

My father died twenty-three years after the close of the camps. He died as a gardener – never realizing the aspirations that he had once held. His death was attributed to alcohol which he had consumed in large quantities as a means of dealing with the anger and frustrations he felt.

It was not until I was in college that I learned about the camp experience. Prior to this time I was told that Manzanar was a small town in California where Japanese people lived. When I learned more about the camps, many aspects of my life and identity as a Nikkei person began to fit into place – the family pressure to “blend” into the society and not rock the boat; the pressure to act the right way and the stress upon education as a means to overcome racial hostility.

It was while I was in college that I became politically involved in the movement for social change. During my first year in college, I was involved in the Free Speech Movement (FSM) at UC Berkeley. The FSM challenged the right of the college administration to determine what could be said on campuses. Today, much of this freedom of expression is taken for granted. This was largely a result of students organizing a campus-wide strike to shut down the campus until concessions were granted. This was my first experience in understanding the power and potential of people acting together in a common effort.

While my identity as a student was affected by the Free Speech Movement, it was the movement of Blacks and other Third World people for equality and justice that affected my identity as an Asian American. What began as a movement for civil rights in the South quickly spread throughout the nation with demands of political power and self-determination for oppressed nationalities. The urban revolts of the ’60s and the fight for justice brought home the fact of institutional racism and that the U.S. was a society where the benefits and privileges were divided by color.

The issue that most affected my political development during the 1960’s was the struggle against the war in Viet Nam. It was the war that brought out the most blatant forms of the contradictions within the society. It was racism that sent a disproportionate number of Third World people to fight and get killed in a war killing other people of color to defend profits for the few. There was the contradiction of seeing billions of dollars being spent each month to maintain a military machine while at home there were claims of not having enough money to feed, clothe, and house the poor.

The student movement, Third World movement, and anti-war movement all helped to crystallize for me the need for a fundamental and basic change within the society. There is a need to change a society that valued profits over people, material goods over human life, and elitism over equality.

From my initial involvement in the struggles of the ’60s came the realization of the need for organization. Thus, many of us worked together to form the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA). The purpose of AAPA was to form an organization that would take progressive stands within the Asian American community – stands in support of other Third World movements, stands against the war in Viet Nam, and stands in favor of developing unity amongst Asian Americans. While AAPA took up a number of issues, its existence was short-lived. The organization was made up primarily of young activists arising out of the movements of the ’60s. Activists who were not rooted within the community. Thus, the base of support for AAPA’s efforts was narrow, and the impact upon the broader community was limited.

With the realization of the shortcomings of efforts such as AAPA, many began to become involved in efforts to integrate within the community. I was involved in the efforts of the JACS-Asian Involvement office in Los Angeles. We rushed headlong into Serve the People programs and created a number of social service programs dealing with drug abuse counseling, food co-ops, child care programs and welfare rights. Many activists became community workers in collectivizing their resources and efforts in order to better serve the community.

As with AAPA, these Serve the People programs met with initial success but were short-lived in their impact. Much of the work was based upon idealistic notions and was divorced from the reality confronting most people in the community. Many of the services and programs initiated were taken over by government-funded agencies.

From the lessons learned from the work with AAPA and the JACS-Asian Involvement office, came a recognition of the need for an organization that would combine politics with integration within the community – a mass-oriented politically progressive organization that would take principled and consistent stands on behalf of Japanese Americans and other oppressed nationalities.

In 1976, the Little Tokyo People’s Rights Organization (LTPRO) was formed to fight against the forced destruction and dispersal of the Little Tokyo community of Los Angeles. We witnessed Japanese corporate businesses in collusion with the federal government and local politicians taking over property held by long-time residents and small businesses. LTPRO was formed in order to facilitate the participation of as many people as possible in defending Little Tokyo. We won some concessions that helped preserve our community, but more importantly, LTPRO provided a long-range strategy for such protracted struggles. Eight years later now, we are still working for more housing, and we continue to uphold the rights of small businesses and community/cultural groups in Little Tokyo. At the same time, LTPRO has expanded its political scope to demand Redress and Reparations, unconditional residency and full rights for Japanese immigrant workers, and no human service cuts in our community.

The issue of Redress/Reparations has come to symbolize the growing strength and maturity of LTPRO. A few years ago, the fight for reparations was but a dream in the minds of a few people. Through the work and efforts of LTPRO and other individuals and organizations, we helped found the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations and we have seen how the dreams of a few have been transformed into a vital movement that has brought together Nikkei people from throughout the country. We have also seen the power and sense of pride that has arisen from this movement.

The development of LTPRO has come to reflect the continuing effort to build a progressive movement for change. The principles and ideals held by many of us during the ’60s and ’70s continue to hold true today: full equality for Japanese Americans and other Third World and working people, full rights for workers and immigrants, and reliance upon democratic principles and mass participation.

The effort to build a better future will be a long and arduous one. It will require a long-range view of achieving social change and a commitment to political principles and perspectives. As I look back at the ’60s and ’70s, I remember many idealists who thought social change would come about quickly. These people soon became discouraged or “burned out” and left the movement. I also remember many individualists who tried to go it alone in creating social change. These people soon found that they could not change the system as individuals and became cynical and defeated.

There are many others, however, who have persevered in the struggle, who have integrated their political ideals and principles into their lives, who have continued to work in a collective manner in the fight for equality and democratic rights. We, in LTPRO, recognize that Nikkei people all across the country share a common history, a common bond, and a common destiny. We are working to unite and organize for the long-term fight against national oppression. As a Japanese in America, I stand proud because by participating in a broad, progressive organization like LTPRO, I’m taking a stand for justice and equality, pride and dignity for our people.

After high school, I went into college and studied biochemistry. I was into a hippie stage ... I was an idealist; you know, “peace, everyone should love one another and everything’ll be alright.” I went to U.C. Santa Barbara in 1968 when the first Third World strikes started happening. We were demanding our rights to an equal education, one that dealt with our people’s histories rather than just falsified European male history. That was the crystallizing thing for me. I took part in anti-war and anti-draft marches. I had watched the Civil Rights Movement and ghetto riots while growing up. It brought changes on and that’s when I decided to drop out of biochemistry to re-think my direction in life.

I got a job in a factory and got involved in my first unionizing effort. Later on, and it took a while, I realized that peace and justice don’t happen by just waving the peace sign, smoking dope, kicking back and being good to your friends. Being good to people is basic but the only way to stop oppression and exploitation is by fighting actively against it in whatever way you can. Seeing people not only in the U.S. but around the world struggling and dying fighting for liberation made me realize that the oppressors will never stop exploiting people because you ask “Please stop . . . gimme a break.” It ain’t gonna happen. I know we have to actively struggle to make progressive changes, and I feel that everyone has a skill or talent to give to making positive change. For myself, I’ve enjoyed art since I was a child, so I felt that’s something that I should pursue.

I really started to make a serious effort in that direction after I moved to San Francisco in 1974. I became involved with the Committee Against Nihonmachi Eviction (CANE) and joined their newsletter committee. I started doing illustrations. From that it progressed and grew. I started doing things for the October First Celebrations, for normalization of relations between the U.S. and China. That’s when I was introduced to the Kearny Street Workshop which was flourishing.

I felt there was a real need on the cultural level to develop skills and promote a Japanese American community art. A couple of us on CANE’s newsletter committee frequently talked about art. We used to talk with others too about the need for some place, a facility we could work out of. A place where we could develop politically conscious art and offer art classes that people normally could not afford. They wouldn’t get the same perspective going just to an art school like the Academy of Art in San Francisco. We wanted more of a grassroots thing basically. So the idea of having an arts workshop in the community came about, and we were able to get some seed money from the Japantown Art Movement, a coalition of community groups that was formed to get funding for community art programs. We got use of the empty space at 1852 Sutter from the Redevelopment Agency. There were people interested at that time, most of whom are still involved: Doug Yamamoto, Rich Wada, Mitsu Yashima, Gail Aratani and others. So we began in early ’76 to rehabilitate the building. By early 1977, around springtime, it was starting to take shape. We put the word out about this art workshop in the community. We had a formal organizing committee and started dealing with what we were going to call ourselves and where we were coming from. We opened on October 1, 1977. That’s how the Japantown Art and Media (JAM) Work-shop came into being.

When we first started, there were basically just classes. We started doing silk-screen posters and that evolved into graphic services. It’s expanded beyond posters to leaflets, brochures and other art services to community organizations. There are special art projects such as the Asian Women Artists Project, Senior Citizen Art Project and Nihonmachi Garden Project. We’re also involved in exhibitions and cultural events like the Oshogatsu Festival and Nihonmachi Street Fair.

When we first started we were totally volunteer. We had some funding from private foundations. At one point we had state money and paid people to work at JAM. But there have been cutbacks. It just means that we will rely more on volunteers and collaborate closer with other progressive art groups.

I feel fairly comfortable with my work now. As the years have gone by I can see the improvement in my work and hopefully that’ll continue. Not being formally trained, the only way you can do it is to keep producing. I think the greatest leaps I have made in the quality of my art have been since working with JAM. This is what PROGRESSIONS (an exhibit of posters and drawings by Wes Senzaki and Richard Tokeshi at S.F.’s Chinese Cultural Center in March, 1982) is all about. We’re not working in isolation. We’re working with other artists and organizations in the context of a community and it’s a process of constant sharing. I learn much from other people as I hope they learn from me.

Up ’til now, I’ve been focusing more on my art in terms of developing craft and skills. I think at one time my political understanding was at a much higher level than my technical art skills. I’ve been feeling though that my art skills have come up to a level pretty much on par with my political understanding. In order to get any further, not only in my art but in my politics, I have to do more study to get a deeper understanding of what’s going on and what needs to be done. My art will always get better as I practice it, but the same holds true for my politics. It will only get better as I practice it.

The Asian Movement, if you look at it historically, is still very, very young. It’s been progressing all along; it’s been expanding. At the beginning, it was almost exclusively a political movement and it’s expanded in the last few years by recognizing the role and power of culture. That’s real encouraging.

Whenever other art/cultural groups like the Asian American Resource Workshop in Boston or Thousand Cranes in New York City are in the area, they stop by JAM and we have some really good discussions. We keep in contact; we send each other literature. It’s funny because you can get the feeling that you’re alone, that no other artists out there know what you are doing. But when other groups start popping up, there’s a sense of a movement happening. It’s encouraging for us, so at JAM we try to be as supportive and helpful as possible.

Though social and economic conditions are deteriorating, I have hope. On an important level, things are getting better. Better because people who have progressive political consciousness, their consciousness is deepening, and for those who didn’t before have that consciousness, they’re beginning to get it. There’s also a growing sense of unity among the Asian nationalities. That’s one thing I’d like to point out about JAM. Even though we focus on the Japanese community because we’re located in Japantown, we work with and for groups of different Asian and Third World nationalities around the Bay Area. Our staff isn’t just Japanese. In the future, we want to get more in touch with other Asian/Pacific nationality communities and build a stronger network of progressive artists.