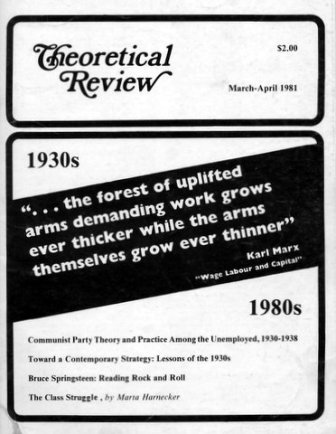

First Published: Theoretical Review No. 21, March-April 1981

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The developing economic crisis of US capitalism, and the significantly new state policies being implemented in response to it by the Reagan administration, present unprecedented opportunities for mass activity and left intervention. The growth of unemployment; the intensification of racism, sexism and anti-communism; the attempts to roll-back the gains made by the civil rights movement and the liberation movements of women and gays; the campaign to liquidate many government services and aid programs, all require our urgent attention. The difficulty is not in finding issues which demand a response from the left, but in developing a general political line within which these various struggles can be articulated.

Without such a general political line, specific to the current conjuncture, it is impossible to assess the intensity of the numerous capitalist contradictions, their relative importance and their relation to each other. Without such a line it is difficult to determine the possible gains and/or limitations inherent in each struggle. Finally, a general political line gives to each struggle a strategic vision and a range of appropriate tactics which it can put into practice, and a framework from which to evaluate if errors are being made in the process.

The need for a correct method and approach to the issues posed by the present crisis is urgent. Our relative lack of contemporary experience obliges us to look elsewhere, to draw on history for lessons of past practice in similar fields. The Communist Party, USA in the 1930s played a leading role in nearly every mass struggle of those years. Without the Party’s efforts many of the social reforms won at that time might not have been obtained. Today, when the current economic crisis appears in certain respects to parallel, or at least foreshadow a replay of some of the economic difficulties of the depression years, it is very tempting to imitate the theory and practice of the Communist Party in its era of greatest success in the hopes that we might achieve similar results.

The accompanying article in this issue of the Theoretical Review on Communist work among the unemployed points out some of the strengths and weaknesses of this particular area of Party activity. The Communists did not take up the battle against unemployment in isolation; their tactics were shaped by their general political line and the strategic response they felt it required. In this sense the way the Communists fought unemployment, racism and war must be judged not only in terms of each of these specific struggles, but also in relation to this general political line, its strengths and weaknesses.

This article cannot examine the totality of specific struggles the Communists helped to lead in the 1930s. That would require several volumes. The accompanying article on unemployment is a contribution toward that study. We hope to have others, on the struggle against racism, and on Communist work in the CIO, in future issues. In this article we can only look at the principal features of the Communist Party’s general political line with an eye to examining how it affected the way the Party took up the various specific struggles in which it was involved. In the process we hope to make clear the nature and importance of a general political line and to stress its importance for serious communist activity today. Because we feel that the political line of the Communist Party in the 1930s was basically flawed, this article will inevitably be concerned with the negative lessons of that period. This is in no way meant, however, to denigrate the many positive contributions which can be learned from the specific struggles in which communist participation was a vital and leading force.

The second half of this article examines the present situation in the United States from a strategic perspective. Here we evaluate the view, prevalent in certain left circles, that the policies of the Reagan administration represent a rising fascist danger, which requires, by way of response, a United Front Against Fascism. Against this perspective we counterpose the Marxist-Leninist theory of fascism which, when applied to current American conditions, shows that the characterization of the principal features of the new administration as fascist is incorrect. Finally we provided an initial formulation of an alternative strategy which we feel more accurately corresponds to the requirements of the present moment. Before going into this contemporary strategy, however, it is necessary to have a beginning perspective on the historical development of the general political line of the Communist Party, USA in the 1930s.

A general Political Line has three principal components: (1) an overall conjunctural analysis; (2) a strategic and tactical line which corresponds to that analysis; and (3) a specific plan of work for the Party itself to render it capable of successfully taking its line to the masses. Let us look at each of these components generally, and as they operated in the theory and practice of the Communist Party, USA in the 1930s.

A conjunctural analysis consists of two inter-related aspects: (a) an assessment of the balance of class forces and the intensity of class and other social contradictions of a society (in its world context); and (b) an assessment of the possible and likely directions of its development as a result of these contradictions and the outcome of class struggle.

In this regard the thinking of US Communists on the nature of the depression, and the economic crises which followed it, underwent a radical shift in the decade of the 1930s which directly affected all the Party’s work. In the first period, 1929-1934, American Communists, like all members of the Communist International, held the view that the world capitalist crisis was creating a potentially revolutionary situation in a great many countries. That is, the Party insisted that class contradictions and the economic “breakdown” of US capitalism were combining to create the possibility of the overthrow of the ruling class.

At the same time it also asserted that the acute character of the contradictions which the crisis revealed was opening the way for another solution to the crisis: fascism. Because it considered these to be the only two solutions to the crisis, the Party slogans in this period were: “Against fascism and war! For a revolutionary way out of the crisis!”[1]

Unfortunately, while fascism and social revolution were possible outcomes of the great depression, they were, in no sense, the likely ones. In reality the economic crisis of capitalism, while real enough, was not a revolutionary situation. Capitalist economic collapse was not inevitable,[2] and capital had vast reserves which it had yet to call up to find alternative ways out of the crisis. Nor were the economic difficulties so severe nor the political power of capital so weakened that some form of the exceptional state (fascism or military dictatorship)[3] was seriously considered as necessary to maintain bourgeois hegemony. Likewise the revolutionary left was far too small and isolated from the masses to pose a serious threat to the social order.

In short, the Communist Party imposed upon the situation in the United States a schema which only took into account two possible outcomes of the crisis, neither one of which was likely, and it ignored other alternatives which were more realistic and probable, given the actual conditions which prevailed at the time. Since the Party’s analysis was based on the economist catastrophist assumption that capital had reached its objective limits and could find no way out of the crisis for itself short of fascism, it failed to seriously consider the alternative of a far-reaching restructuring of the capitalist economy and state as a different possible outcome of the depression.

If the Communists ruled out this possibility from the beginning, the struggle within the capitalist power bloc and the state was largely fought over that very issue: the nature and extent to which capitalism would have to change in order to overcome the structural obstacles to capital accumulation. Herbert Hoover’s traditional austerity offensive had proven its inability to cope with the depression; now it was the turn of the Keynsians, the “social planners,” the New Deal. The most far sighted among them saw the need for a new capitalist social order which would couple massive state aid and state intervention in the economy with programs to organize and integrate the masses into the state system in order to co-opt and neutralize their independent initiatives. Other sections of the power bloc resisted the full application of this program and the rest of the decade was shaped by the continuing conflict over how far to go, how fast, and by what means.

In the 1929-1934 period the Communist Party failed to appreciate this conflict and spent its time absorbed in illusions about the unfolding situation. It denounced the threat of a fascist takeover in Washington: “American capitalism is more and more fascising its rule. This is particularly being performed by the Roosevelt administration under the cover of the ’New Deal’.” It called for the transformation of mass struggles against unemployment and hunger into “general class battles for the overthrow of capitalist dictatorship and the setting up of a Soviet government.”[4] Not only did this illusory perspective lead to erroneous and “ultra-left” tactics, it also prevented the party from actively influencing the actual historical process as it unfolded. By the time the Communists realized that its “fascism or revolution” scenario was wrong (1934-35), the New Deal restructuring was well under way.

In line with the thinking of the Seventh Congress of the Communist International, held in Moscow in 1935, the Party now shifted gears and came up with a different conjunctural analysis. It concluded that the United States was no longer in a revolutionary situation, and that therefore the struggle for a Soviet America was no longer on the agenda. But, as before, rather than make its own careful assessment of the actual direction in which capitalism was going, the Communist Party again imposed another schema on this country. This one, developed by the Seventh Comintern Congress in response to European conditions (where the fascist danger was very real) concluded likewise that in the United States the only paths open were either “fascism or democracy.”

Fascism was and is always a danger under conditions of advanced capitalism. But a correct conjunctural analysis and strategy must do more than merely note the presence of dangers. It must, above all, determine the principal aspect of a situation (“grasp the key link”), and from there, the relative significance of other, lesser links. Fascism was the principal danger facing the German workingclass in the years 1929-1933.

Fascism was also a serious danger in other European countries in the 1930s. So too was military dictatorship, for that matter (Spain and Portugal are examples). But fascism was not a primary or the primary danger in other countries at that time, including the United States. That is, the necessary factors for a qualitative shift to fascism never matured in this country in the 1930s, for reasons we will discuss later in this article.

The error of the Communist International and the Communist Party, USA after 1929 was to ignore Lenin’s conception of the uneven development of capitalism, which saw capitalist development proceeding differently and at a varying pace in different countries. Instead the Communists adopted the view that all capitalist countries were developing toward fascism at an equal pace, and according to the same general plan. From this identity of development was naturally deduced the necessity of uniform strategy and tactics in the Communist response.

Although it could be disregarded in theory, uneven development continued to govern the reality of the world situation. US Communists were ultimately saddled with an analysis and line which did not correspond to the actual conditions they were facing. The Party saw contradictions within the ruling class, but it failed to correctly identify the protagonists because the schema “fascism or democracy” obscured the issues which were at the heart of these contradictions. The struggle within the power bloc was not between supporters of fascism and supporters of democracy, but rather over the new forms that bourgeois democracy should take in order to pull the country out of the crisis.

Unfortunately, the Communists did not perceive this. They viewed the parties to this conflict in a different light. On the one side were those forces which they identified as “fascists,” or as Browder was fond of calling them, after Roosevelt, “economic royalists.” Ultimately all anti-New Deal politicians were included by the Party in this camp, even the Republican presidential candidates nominated to run against Roosevelt. Yet, as noted above, fascism was never the issue around which these forces were mobilized. In fact, their central concern was always to limit and curtail the restructuring program of the New Deal. This was certainly a reactionary orientation, but it would be a mistake to call it fascism.

If opposition to the New Deal was equated with fascism, support for it, and Roosevelt himself, increasingly came to be equated with the struggle for democracy in the eyes of the Communist Party. In 1938 it did not run its own candidates in the elections but threw its support to the Democrats. In Browder’s words:

“Victory for the New Deal Party means keeping our country on the path of progressive and democratic development .... That is why the Communist Party clearly and without hesitation declares its support of the New Deal Party and policy, proposes and works for the unity of the majority of the people behind a single progressive candidate for each electoral office, subordinates itself and its own particular ideas to the necessity for this broadest unity of the majority of the people.”[5]

All the Party’s best wishes to the contrary, the New Deal did not represent a democratic impulse, but rather the realistic political perspective of advanced sections of capital, moderated by compromises and concessions demanded by other sections. Abstractly characterizing these forces as “democratic,” the Party fostered illusions about the true nature of the New Deal and the class nature of bourgeois democracy.

While capitalism was being reconstructed on new foundations, Communists failed to guard against the neutralization and integration of mass struggles under the impact of New Deal reforms. How this was done is our next topic.

A strategic and tactical line is an overall plan of action which corresponds to the likely direction of development of a society and reflects the interests and demands of the workingclass and oppressed people in response to it. A strategic and tactical line sizes up the possibilities inherent in every stage of capitalist development and formulates a battle plan that will ensure the maximum extension and/or defense of workingclass interests. When capitalism is going through a period of necessary restructuring, as it was in the 1930s, and as it is now, a strategic line seeks to organize the intervention of the masses in the process to compel concessions and a restructuring most favorable to their interests and the strengthening of their position vis-a-vis other class and social forces.

A strategic and tactical line has two components: (a) a political program which specifically articulates the various social struggles which it seeks to guide in their hierarchy of importance, and which sets goals and tactics appropriate for each; and (b) a mass line which conceptualizes and concretizes the relationship (learn from/teach) between the party and the masses.

In the 1929-1934 period the Communist Party, thinking that revolution was on the agenda, adopted a corresponding revolutionary strategic and tactical line. Following the erroneous, ultra-left line imposed upon the Communist International by the victory of the Stalin group in the Soviet Communist Party, American Communists abandoned the Leninist policy of the united front which they had been patiently pursuing and, henceforth, rejected all joint activity with other left and progressive forces. Since the alternatives could only be fascism or revolution, and only the Party represented the revolutionary way, all the other left and labor groups were relegated to the “swamp of social fascism,” including the American Federation of Labor (AFL), and the Socialist Party. In line with this strategy for revolution the Communists pulled the bulk of their cadre out of existing unions and mass organizations and set up exclusive dual unions and revolutionary groups of their own.

Had there been an actual revolutionary situation, revolutionary tactics would have been a clear necessity, although it is hard to see how the sectarian and mechanical tactics which the Party actually implemented could be described as revolutionary. In the absence of such a situation, however, they were even more damaging. Communists found themselves isolated from many struggles and isolated within many others. In their work among the unemployed, sectarianism prevented a broad united front of all unemployed organizations from developing a unity which would have made the movement stronger and more effective. Finally, the unrealistic ultra-left orientation limited the Party’s size and ensured a high membership turnover.

Even though the ultra-leftism of the Party’s line crippled its ability to understand the unfolding historical process and isolated it from broad sections of the masses whom it sought to win in revolution, the Party’s militancy, commitment and leadership skills had a catalytic effect in many fields of struggle. The Communist Party took the lead in championing the battle for social security and unemployment insurance. It pioneered in the formation of industrial unions. Its work around the Scottsboro case brought the struggle for Black liberation to millions. However, except in the movement of the unemployed, the Party was never able to create viable mass organizations supporting its views in this period. Rather, it forged small, militant fighting units whose members, in the next period, were thrown into the broad mass arena where they frequently rose to leading positions.

In 1935 the Communist Party recognized, with Comintern help, the need for a change in its strategic and tactical line. The obvious dynamism of the on-going capitalist transformation demanded that the Party examine, the direction of development of this transformation, its possibilities and limitations. What was needed was a strategic and tactical line which could take advantage of the transformation to at least wrest significant economic and political concessions from capital to the benefit of the workers and oppressed peoples. Such a line was also required to ensure that, in the course of this struggle, the independence, flexibility and fighting role of the workingclass not be sacrificed or subordinated to other class interests, and that capitalist illusions being spread by the New Deal reforms be successfully combated. Armed with such a strategic weapon the Communist Party and the tens of thousands who followed it could have been able to exert pressure on the transformation process from the “left,” to push it in a direction more favorable to the long term interests of working and oppressed people.

Unfortunately the Communist Party chose a different course, or rather, a different course was chosen for it by the Communist International. This was the line of the United and Popular Fronts which developed after the Seventh Comintern Congress. Although the need for unity of all anti-fascist forces had been clear for many years, the strategic recognition of this necessity had been forbidden to the Communist Parties in the years 1929-1934. Now it was once again on the agenda, and for Communists fighting against a rising fascist danger, or fascism in power, it was a great step forward. For all communists the change was also important in that it brought an end to the sectarianism, the label of “social-fascist,” and the dual unionism which had characterized the strategy of the 1929-1934 period.

At the same time, however, in countries dominated by a political process other than fascism, such as the United States, the anti-fascist strategy was inappropriate. It failed to grasp the key link: capitalist restructuring within the limits of bourgeois democracy, while it elevated a lesser factor, fascism, to first place. With these misplaced priorities the Communist Party directed much of its energy against the lesser enemy and allowed the central factor, the New Deal restructuring to proceed with a free hand.

But there were more problems with the Popular Front strategy than the fact that it was applied to countries which required an alternative approach. The actual practice of this strategy represented a significant departure from the Leninist strategy of the United Front, advanced by the Comintern in the early 1920s. The Leninist strategy had been based on a class policy, positing a united front of workers’ organizations which would then rally the non-proletarian masses to its banner (the forging of a national-popular bloc). It presumed the necessity of proletarian hegemony within this broader formation which would direct itself against the capitalist system. While recognizing that sometimes there would be an objective coincidence of interests and action between the national-popular bloc and certain sections of the bourgeoisie, Leninism rejected the notion of binding alliances with capital or its political parties as class-collaborationism.

The Popular Front line, as practiced after the Seventh Comintern Congress, significantly departed from this tradition. The Popular Front of all anti-fascist parties, including sections of the bourgeoisie, took precedence over the united workers’ front. Dimitrov’s definition of fascism at the Seventh Congress had opened the door to this turn of events. As was pointed out at the time,[6] Dimitrov’s restriction of the class base of fascism to only the “most reactionary, most chauvinistic, most imperialistic” sections of finance capital, implied that other sections of capital could be won to an anti-fascist policy. In practice the abandonment of the class-based united front strategy for a non-class one of alliances with bourgeois parties soon led to class collaboration and the subordination of workingclass interests to those parties in the interests of “anti-fascist unity.”

Present-day defenders of the Popular Front line insist that without this anti-fascist unity, world fascism would not have been defeated. Everyone can agree with that statement. The issue that divided the communist movement, however, was how best to achieve that unity: through subordinating the masses to an inconsistent and vacillating bourgeois section which would not fight, or through the organization of the masses around a clear anti-fascist political program. Genuine Leninists, who had fought for anti-fascist unity in the 1929-1934 era when it was labeled a “social-fascist trick” continued to fight for it after the Seventh Congress.[7] They never opposed united action. What they were against was unity on terms favorable to the bourgeoisie and bourgeois democracy, the strengthening of capitalism at the expense of the popular movement.

After briefly considering the possibility of some kind of independent labor party in 1935-1936 as the best expression of the Popular Front, the Communist Party turned in 1936 to a line of critical support for Roosevelt and the New Deal. This support became increasingly less critical in the next two years so that by 1938 the strategy was renamed the Democratic Front, a sign of its closer alignment with the Democratic Party’s liberal wing. Basing this change on an abstract defense of “democracy” and concrete support for the Democratic administration, the Communists were swept up and carried along as the “left-wing” tail of the New Deal restructuring, explaining their behavior by the pressing need for anti-fascist unity.

Browder did not attempt to conceal this subordination (liquidation) of communist politics. After repeating the Party’s commitment to support the Democratic Party candidates in the 1938 election “without hesitation,” he added:

“It should not be necessary to repeat here that there is nothing of Communism or socialism in the platform of the broad democratic front, of the New Deal or of its main support. Nor do we of the Communist Party propose to insert anything communistic or socialistic in it. We do not propose to ’push Roosevelt to the left.’”[8]

Nowhere was this abandonment of communist politics clearer than in the Party’s mass work, and nowhere else were its effects more damaging. The Communists more clearly than anyone else recognized the importance of winning basic economic reforms in the course of mass struggles. The fault was not in the energy or the organization which Communists brought to these struggles, but in the line which they sought to impose on them. The advanced elements of capital were willing to grant unemployment insurance and social security when forced by mass pressure, but they sought to use these economic gains for the workingclass to capital’s own political advantage: the cooptation and integration of these struggles into the State system, the destruction of their independent character, and their harnessing in the service of the Democratic Party. In this regard the Communist Party’s subordination of all its efforts to the New Deal agenda and its State system perfectly coincided with the requirements of capital that mass struggles be brought into line behind Roosevelt.

The example of the battles of the unemployed is a case in point. Once the State set up an unemployment insurance system the Democratic Front line dictated that the Party give primary attention to the unity of all democratic forces, which meant working within the state administrative apparatus. The center of Communist activity shifted from mass struggles to administrative procedures, from the organization of neighborhoods to the filing of grievances. From an independent and combative mass process with its own dynamic, the movement of the unemployed under communist leadership was channeled into a safe and docile appendage of the Democratic Party.[9]

If, in the previous period, the Communists had made “left” errors in fighting for a revolution which was not on the agenda, in this period, it consistently made “right” errors, by failing to make use of the possibilities inherent in the situation to push things to the left. A strong movement of the industrial unions, the unemployed, the organizations for Black liberation, against war, and for student’s rights, united and independent of the Democratic Party, could have exerted the necessary pressure to win political concessions and make a more progressive restructuring than the New Deal a reality. The failure of the Communist Party to use its considerable influence and prestige to forge such an independent left coalition was the basic flaw in its general political line of this period.

How was it possible for the Communists to influence mass organizations which they dominated to follow a policy which was antithetical to their long term interests? The answer to this question can be found by examining the Communist Party’s mass line, its conception of the role of the masses in the revolutionary process.

A mass line is indispensible for any communist activity. Communists can give organization and heightened consciousness to mass movements only by closely linking themselves with the people, learning from them, and helping to give direction to the tremendous energy of their spontaneous struggles. As Louis Althusser says, “a party must be judged in accordance with its capacity to give attention to the needs and the initiatives of the popular masses.”[10] A living, open and attentive attitude toward these struggles is an indispensible aspect of the mass line.

The Communist Party in the 1930s, however, had a different conception of the mass line; for it accepted without question the Stalinian notion of mass organizations as mere “transmission belts,” mechanisms for transmitting the line of the party to the broad masses. Primary attention was paid to the organizational measures necessary for facilitating smooth communications between party and mass organizations and for ensuring that the line of the Party was promptly implemented in them. Scant attention was paid to ensuring that these organizations developed a real, active life of their own; and signs of independent activity were often viewed with indifference, suspicion or hostility.

For the Stalinian deviation, then as now, it is not the masses who make history, but the Party. The masses are reduced to being the instrument through which the Party works, bringing about revolutionary change.

For a Communist Party, guided by the Stalinian conception of history, the transformation of the masses from passive subjects into active agents in the historical process was not essential. It was enough that they looked to and followed the Party line. Communists were largely content with ensuring the existence of large mass organizations which would: (a) faithfully follow the line, no matter what the twists and turns; (b) be useful for mobilizing people behind the numerous Party campaigns; and (c) provide a favorable terrain for recruitment. The practice of constructing mass organizations of this type, controlled from outside, and lacking an active internal life of their own, was the essence of the Party’s mass line in this period.

The rank and file of these organizations played an invaluable role in the great class battles of the time. Yet within the organizations themselves they were not afforded sufficient opportunity to actively participate in line formation and interpretation, at leas; on the national level. Instead, they were frequently confronted with top-down bureaucracy and an organizational machinery which did not provide adequate channels for effective proletarian democracy. This problem, the lack of on-going democracy, was not only present in the Party’s mass work, but in its internal life as well, which is our next topic.

The third component of a general political line is a specific plan of work for mobilizing the Party itself to undertake the implementation of its strategic and tactical line. This plan involves two organically related aspects; political and organizational. The former includes establishing and guaranteeing the necessary conditions for theoretical practice, and the constant development, refinement and rectification of the political line. The latter involves the organizational mechanisms for cadre training and development, and the reproduction of the mechanisms of democratic discussion to ensure the maximum participation of the entire party membership in political practice and its evaluation and rectification.

Throughout the 1930s the Communist Party’s internal political practice was crippled by the acceptance of the Stalinian caricature of the Leninist Party. The victory of this caricature was bought at a heavy price: the expulsion or resignation of a majority of the Communists who had joined the Party in the 1920s. In 1934 Browder admitted that ”a majority of our Party members are less than two years in the Party.” He also noted a serious fluctuation in the then current membership, pointing out that ”two out of every three recruited members have not been retained in the Party.”[11] This same problem, if not the same percentages continued to plague Communists throughout the 1930s.

The reasons for this problem are complex, and it would be too simplistic to try to reduce them to a single cause. Nonetheless, the enumeration of the general features of the “monolithic party” of the Stalin era points to a number of the most obvious factors. The Party was ruled by bureaucratic centralism, which meant the absence of meaningful inner-party democracy. As a result there was a sharp dichotomy between leaders who determined policy and members who carried it out, inadequate theoretical and political training of the rank and file, and a remoteness of the leadership from actual conditions at the base.

Theoretical practice was never a high priority of the US Communist Party in the 1930s. What little theoretical work there was, was provided largely by the Communist International and its representatives, by Comintern-trained students, or by a small circle of top leaders. Any deviations from official positions were viewed with profound suspicion and creative independent thinking was encouraged in name only. The recurring polemics against “American exceptionalism” blocked any authentic conjunctural analyses of the basic features of US capitalism so that only the official view of the evolution of American society prevailed.

“American exceptionalism,” the way the Communist Party described it, never existed. What was called “American exceptionalism” was, in fact, the development in the Party in the mid-1920s of an open and critical attempt to concretely analyze US reality free of pre-conceived dogmas. These efforts were directed toward the production of theory and tactics of immediate relevance to US conditions. When this theory and tactics did not correspond with the “universal” conclusions proposed by the Comintern, their authors were accused of believing that the United States was an exception to the “universal” laws of capitalism. In fact, they were only arguing that American conditions did not correspond to the ”universal” schema which the Comintern had constructed. These “American exceptionalists” were defeated in 1929, and a conjunctural analysis based in the particularities of US conditions was put off indefinitely by the Communist Party. From then on the Comintern’s word was unquestioned authority when it came to problems of strategy.

The specific application and reformulation of strategy for implementation by the Party membership was accomplished by the leadership core of the Central Committee, with the help of Cominterm representatives. The duty of the rank and file was not to question the line or its correctness, but only to undertake the most effective means of its implementation. This passivity and uncritical spirit fostered at every level of the organizational hierarchy, as well as the replacement of democratic discussion and debate by ritual speechmaking, and the adulation of the leadership, all took their toll on the Party’s inner life and its fighting spirit. Seen in this light, the ability of Browder to liquidate the entire Party from the top-down in 1944, with only token resistance on the part of the membership, is perfectly understandable.

If democratic centralism did not function, cadre development was also given a low priority. True, the Party ran a number of important cadre schools and Party districts had their own leadership training programs. Teaching was done almost exclusively from the classics and the writings of Stalin, Dimitrov and Browder. This exposed the student to a great deal of important literature, but, as a rule, they were taught to read the texts uncritically and to learn to use theory to explain political decisions after the fact rather than as a guide to political practice.

Many cadre did not even get the opportunity to go to these schools or training classes. Whatever they learned, they learned it in the mass struggles in which they were involved. These cadre, particularly those in leadership positions in the mass movements, more than anyone else, needed advanced political training to enable them to keep their bearing in the complex and rapidly changing conditions of their work.

Unfortunately many of them who were recruited out of the mass struggles remained at their posts without this education in Marxism. They gave the whole of their lives as representatives and recruiters for the Party, but often failed to make the transition from mass fighter to communist cadre which a genuine vanguard party requires. Nowhere was this failure to sufficiently develop the Party membership clearer than in the trade union movement. For all the honest communists who stuck to their post through the 1930s and into the McCarthy period, there was an equal number who deserted the Party once the going got rough.[12]

Even so, in their time, these latter trade union militants provided the Party with the kind of communists it needed in mass work: loyal supporters who would faithfully carry out the line in their own organizations, yet who would be lacking the necessary theoretical and political development to ever effectively challenge it. This was the division of labor which the Stalinian party produced: between full time political leaders and mass activists who found a whole series of reasons to work together for their mutual benefit. With the Taft-Hartley Act and McCarthy there came a parting of the ways, not for reasons of politics, but for reasons of narrow self-interest. The Communist Party suddenly found itself a general staff without an army.

Summing up the lessons of the 1930s we should say that the Communist Party and its members made an invaluable contribution to the struggles of those years. Without their energy and sacrifice many of the gains achieved might not have been won as fully or as quickly as they were. Yet, at the same time it must also be said that the full potential of those years was never realized by the Communists and that many gains could have been expanded and strengthened and many others won if the party had been guided by a more accurate general political line. Energy, enthusiasm, commitment and sacrifice are necessary, but only a clear and concrete analysis of a situation which recognizes the full potential inherent in it can set those positive traits of communists to work in the best possible way.

The importance of a general political line to guide the activity of US communists hardly needs emphasizing. Without it our practice lacks effective guidance and our perspective a clear vision. Without it we have no framework within which to evaluate events, no strategy to help us to see beyond our day-to-day work. “A concrete analysis of a concrete situation is the living heart of Marxism,” said Lenin. Coming to terms with the shift to the right in the United States today and its implications for the future requires just such an analysis if we are going to meet the challenge.

As we see from the history of the Communist Party, USA in the 1930s, one of its central weaknesses was the failure to make that kind of analysis. Instead of a correct approach: starting with an analysis of the objective situation, its contradictions and trends, and then developing corresponding strategy; the Communists were given a strategy by the Comintern and then attempted to understand reality based on its directives. When reality did not develop the way this strategy predicted, events took the Party by surprise, or passed it by entirely.

The 1930s were a period of fundamental crisis and transformation for American capitalism, during which it underwent structural changes with long term strengths that have lasted a quarter of a century, but with weaknesses that are only now becoming fully apparent.[13] Today we are in the midst of another such structural crisis for which cosmetic changes and stop-gap measures are inadequate. Capitalism is changing, economically, politically and ideologically. The shift to the right shows the extent to which some sections of capital are willing to go in order to resolve the crisis at the expense of working and oppressed people. Whether the entire power bloc will unite with this reactionary program still remains to be seen.

The present period urgently demands from us more than warnings and platitudes. We need a general political line to orient our work: a conjunctural analysis and a strategic and tactical line which accurately assesses the changes we are now seeing and the likely direction they will take in the future. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the ultimate test of every revolutionary organization in this country is going to be its ability to find its bearing in the present crisis and to chart a correct course for the struggles ahead.

Everyone on the left has recognized that militarism is on the rise and the danger of war is increasing, Everyone recognizes that class, racial and sexual contradictions have intensified and are going to further intensify in the foreseeable future. Everyone also recognizes that the present economic crisis and all the suffering which accompanies it are not going to disappear without far-reaching changes in every sphere of life. At the same time the left is cognizant of its own small size and ineffectiveness and the undeniable need for the broadest unity of forces to mount a counter attack against the austerity offensive which is being unleashed. The principal ingredient which is lacking is an accepted conjunctural analysis of the situation and a strategy acceptable to a wide array of organizations and individuals.

That is why a general political line is so important. It alone can provide the overall context in which we would be able to situate each particular contradiction and struggle and evaluate its relative importance. We all have a general understanding of the nature of the class contradiction, of racism, and of women’s oppression. What we need now is a specific statement of the forms these contradictions are taking in the present moment of the crisis, how capital can exploit them to its advantage, and the most effective ways of fighting back.

Take the issue of racism. We need a general political line to accurately characterize its importance for the production and reproduction of capitalism in the present conjuncture and to specify the articulation between racism and other capitalist contradictions. We need this orientation to provide guidelines in terms of what gains can realistically be wrested from capital in the present crisis and what previously won gains may be lost if mass struggles do not develop in time. We need this orientation to give us the basis of a strategy for anti-racist struggles and for the correct tactics appropriate to that strategy.

The danger of attempting to take up a single struggle in the absence of such a general political line should be clear. Last year the Organizing Committee for an Ideological Center (OC-IC) set itself the task of mounting a struggle against racism without the necessary political framework. The OC-IC did not start from a concrete analysis of the state of US capitalism and the need for a struggle against racism in capitalist society, but from its own perspective on the state of the communist movement and the need for a struggle against racism within the OC-IC. The lack of a correct political orientation led the OC-IC into a bitter internal struggle which did not help the mass anti-racist movement but went a long way toward destroying the OC-IC itself.[14]

Different forces on the left have provided varying responses to the Reagan election and the general shift to the right. Democratic Socialists, including the New American Movement (NAM) and a number of writers for In These Times, have generally underestimated the depth and structural underpinnings of the current changes. Other democratic socialists such as David Plotke have made a more serious study of the unfolding crisis. Plotke’s perceptive commentaries[15] are marred, however, by a theoretical eclecticism and the ambiguous treatment of a number of central concepts in Marxism. Nonetheless, they show that sections of the democratic socialist movement are serious about exploring new theoretical and strategic avenues of potential benefit to all Marxists.

The Leninist Left has by and large reacted to recent events by overestimating the change: viewing the rise of the right as an example of the rise of fascism. The most extreme expression of this response is the conclusion that Reagan’s election means that a fascist movement has captured control of the national government.[16] Most groups prefer to see the situation in terms of a rising fascist danger posed by Reagan’s policies and the new right. All of which is very reminiscent of the way some Marxist-Leninists saw a fascist movement on the rise during the Nixon years.

Why are so many of these groups raising the question of fascism once again? Is there merit to the attribution of fascist characteristics to the new Reagan administration and its policies? Having looked at the experience of the Communist Party, USA in the 1930s, we can better answer these questions with regard to the present conjuncture.

The shared legacy of pre-1956 Marxism seems to be the principal reason why the bulk of the Leninist left in the United States, from the Communist Workers Party to Line of March, have embraced the theme of a “rising fascist danger.” Just as the Communist Party, USA in the 1930s started from a strategy and then adjusted reality to make it correspond to a pre-given scenario, so too with contemporary groups. They begin either with the Third Period strategy (“for a revolutionary way out of the crisis”) like the Communist Workers Party, or with the United Front Against Fascism, like Line of March. In either case they find fascism everywhere on the rise and urge others to join them in their strategy against it.

These groups are specifically alleging that the Reagan administration’s policies of war and racism are the “bedrock” of a rising fascist danger. Before evaluating this claim it is necessary to have an adequate understanding of fascism itself. Not so much the ever-present fascism of the KKK, the Nazis, etc., but rather fascism as a particular outcome of class and political struggles in the replacement of a form of bourgeois democracy by a fascist state. Before looking at the necessary conditions favoring the rise of fascism, it can be useful to examine a number of erroneous assumptions prevalent on the left about the nature of fascism.

(1) Every organized attack on the conditions of the masses is an expression of fascism.

This view reduces the political policies of capital to two choices: either bourgeois democracy and social concessions, or fascism, repression and social cutbacks. The problem with this perspective is that its definition of fascism is too broad, while its understanding of bourgeois democracy is too narrow. In fact bourgeois democracy is a relatively broad and flexible system of class rule which allows for capital to advance and retreat, for both concessions and austerity measures. Fascism is not reducible to every assault on the people, but rather is a particular, exceptional form of political and state power which only arises under specific conditions. To interpret every overt attack on the people as fascist is to ignore the various reactionary and authoritarian forms of bourgeois democracy. In fact, this view actually reproduces ruling class ideology within the left because it conveys the impression that bourgeois democracy is some kind of neutral or passive form of political power which is constantly threatened by fascism, rather than seeing the germs of fascism that are the organic product of bourgeois democracy itself. The history of capitalism is full of austerity offensives, military campaigns, and the intensification of social contradictions which were carried out fully within the limits of the bourgeois democratic form.

(2) There is an “inherent tendency” toward fascism, “ever present” in bourgeois democracy.[17]

It is important to see that the germs of fascism are present within bourgeois democracy, and that there is a tendency for these germs to develop. But taken out of context this tendency is highly misleading. The tendency toward fascism exists subordinate to another tendency: the tendency of bourgeois democracy to reproduce itself.

The most effective, most flexible and most stable form of the capitalist state, under conditions of advanced capitalism, is bourgeois democracy. It provides the most favorable conditions and suitable forms for the reproduction of capitalist hegemony: the organization and consolidation of the ruling class, and the disorganization and disorientation of the masses. In short, bourgeois democracy in all its varieties is the state form which most closely corresponds to the capitalist mode of production.

For these reasons the dominant tendency in capitalist politics is to produce and reproduce bourgeois democracy. Modern forms of the exceptional state (fascism, military dictatorship) are the product of a subordinate tendency which becomes dominant only under specific conditions of acute crisis in which bourgeois democracy has become an obstacle to the reproduction of capitalist hegemony. Because of its extreme character, its instability and its explosive contradictions, a fascist solution is something capitalism tends to avoid, except as a last resort. Only exceptional conditions give rise to forms of the exceptional state.

(3) The question of fascism is “never far from the minds of monopoly capital’s political representatives,” or, put another way, under conditions of crisis capital’s “preference” for bourgeois democracy “begins to wane” and it increasingly turns to fascism as the “political instrument” best suited to its class interest.[18]

This is the voluntarist-instrumentalist conception of fascism in a nutshell. Whether we have bourgeois democracy or fascism is not a matter of class and political struggles (the balance of social forces), but one of the ruling class’ will–its “preference.” Bourgeois democracy and fascism are not seen as complex political processes, condensations of class powers and class contradictions, shaped by the sum of social struggles in a society. Rather they are simple “instruments” which capitalists employ when it suits their interests.

This erroneous analysis shows that voluntarism and instrumentalism are deviations which express themselves beyond the abstract level of the “general theory of the state.” They also appear at much more concrete levels: our everyday analyses of the functioning of bourgeois politics. Voluntarism and instrumentalism produce a vulgar caricature of Marxist theory which can produce serious errors when attempts are made to put it into practice. In demarcating ourselves from these deviations on the Marxist theory of fascism we must always keep in mind the important political stakes involved in this struggle.

Briefly stated the Marxist theory of fascism can be summarized as follows:[19]

(1) Fascism is a form of the exceptional state which corresponds to the imperialist stage of capitalism. It is a qualitatively different form of state power than bourgeois democracy and it arises only under specific conditions.

(2) Fascism is one particular outcome of an organic crisis of capitalism in which an economic crisis, coupled with grave political and ideological difficulties, cannot be resolved through traditional forms of political practice. But not every organic crisis results in the victory of fascism. An organic crisis in Russia in 1917, for example, led to the Bolshevik revolution. Just as a revolutionary situation has essential preconditions which create it, so too, the rise of fascism can only take place under particular conditions.

Fascism develops out of the presence of two principal factors. First, a crisis in which the power bloc finds itself unable to resolve or neutralize the contradictions between itself and the masses by bourgeois democratic means. Second, a crisis in the workers movement which, while strong enough to constitute a threat to capital, is incapable of creating the national-popular bloc of forces to overthrow capitalist hegemony. The convergence of these two factors, and the rise of fascism in response to them are manifested at all levels of society.

(3) At the level of the power bloc, capital’s bourgeois democratic structure and organizational forms for coping with its own internal contradictions now constitute an obstacle to the effective resolution of the organic crisis. A new power bloc is required and fascism proceeds to provide one through the creation of an alliance between the petty bourgeoisie and monopoly capital under the hegemony of the latter.

(4) At the level of the petty bourgeoisie and other middle strata the crisis leads to a rupture in the hegemonic relations between them and traditional bourgeois parties. Having detached themselves from their former political leaders, these middle strata become a mass base for the developing fascist movement.

(5) At the level of the workingclass the crisis has put the masses on the defensive, but has not frontally defeated them. Fascism provides the basis to bring the masses back under the control of the power bloc: organizing and integrating them into the new fascist state system by means of ideological mobilization and regimentation; disorganizing and atomizing them by means of physical repression.

This was the situation which developed in Italy in the early 1920s and in Germany in the early 1930s. Both these countries were, like Russia before them, weak links in the world imperialist chain. In both Italy and Germany the traditional power bloc found itself incapacitated by the onset of an organic crisis. The disproportionate presence within the power bloc of historically anachronistic class forces (semi-feudal large landowners, Junkers) created structural obstacles which prevented the all-sided transition to monopoly capitalism within the limits of bourgeois democracy. The only way for monopoly capital to reorganize the power bloc in a way favorable to resolving the crisis on its own terms was to forge an alliance with the petty-bourgeois masses against the traditional bourgeois democratic system. The way was opened for fascism and the divided and demoralized workingclass was too weak to provide an alternative pole to attract the middle strata disenchanted with the old parties and looking for a way out of the crisis.[20]

This same scenario was not repeated in Britain or the United States in those years. The reasons for this may be summarized as follows. Although the United States experienced an economic crisis similar to the one which affected Germany and Italy, the political crisis of the US power bloc took a different form. Here there were no anachronistic class forces represented in the power bloc to create a structural obstacle to the reorganization of power in favor of a necessary restructuring of the state and its role in the economy. Hence there was no breakdown of bourgeois democracy, requiring a fascist solution. The structure and mechanisms of the US power bloc were sufficiently flexible to allow for the triumph of the interventionist New Deal state within the framework of bourgeois democracy. The petty bourgeoisie and the workingclass were neutralized or integrated under capital’s hegemony in this process of transformation by the Democratic Party and the host of social reforms initiated by the Roosevelt administration.

Clearly, it should not be argued that the development of contemporary fascism must proceed by way of the same circumstances which produced it in the 1920s and 1930s. Nonetheless, the central focus of our analysis presented above retains its vitality. Fascism becomes a serious threat only under specific determinant conditions. The most important conditions relate to the requirements of a capitalist solution to the organic crisis in which the system finds itself. If the necessary solutions can not be taken up and implemented through bourgeois democratic channels, whether traditional or new, then some form of the exceptional state, fascism or military dictatorship, becomes a serious possibility.

Looking at the present situation in the United States, all evidence points in one direction. Stepped up militarism and intensified class, racial and sexual contradictions are increasing the depth and extent of the overall social crisis. Traditional structures of hegemony and power have already been modified: the government’s role in the economy, the role of fundamentalist religion in politics, the resurgence of national chauvinism and sectional politics. The limited gains made in the field of civil rights and civil liberties are facing significant new restrictions at the hands of the Reagan administration and its Congressional supporters. Increasingly, power is being concentrated in the executive branch, and governmental secrecy and indifference to public needs are on the rise. US imperialism promises to intensify its intervention abroad and to shore up and extend its hegemony wherever it is threatened.

The basic problem for the left is one of evaluating these developments and their political significance. These programs could be the beginning of the rise of fascism to power in the United States. On the other hand, this program could equally be conducted entirely within the tradition of US bourgeois democracy. Which in fact is it? The answer to this question is determined by the nature of our conjunctural analysis and in turn determines our strategic and tactical line.

We could hardly promise to provide a definitive answer to this question on the basis of our own limited research. At the same time we think that we can safely draw a number of general conclusions which appear to us to provide the most accurate picture of the direction in which events are proceeding. The United States is undergoing a crisis of capital accumulation which is structural in character and which can be resolved only through a basic restructuring of capitalist social relations.

We believe that US capitalism has not reached its ultimate limits and that the current blockage of accumulation can be overcome within the confines of capitalism itself. That is, there is no fundamental structural obstacle within capitalism to the resolution of the present crisis. There is also no prospect that a revolutionary situation will develop in the foreseeable future. The way out of the crisis is most probably going to be a long-term restructuring of capitalist relations of production. It appears that for now, as in the 1930s, the decisive question is: what kind of restructuring is it going to be?

Our opinion, based on the work of Nicos Poulantzas, Manuel Castells, Christine Buci-Glucksmann and others, is that the resolution of this crisis in the developed capitalist countries is proceeding, not through fascism, but through a new, more repressive, form of bourgeois democracy, authoritarian statism.[21] It is our view that the drive toward militarism, austerity measures and increased employment of racial divisive policies are not aspects of rising fascist danger, but rather expressions of the new face of bourgeois democracy: authoritarian statism. Further, in our opinion the position that these current policies are signs of imminent fascism fosters the erroneous view that somehow militarism and racism are not fundamental features of bourgeois democracy, but fascist exceptions to it.

As we all know, this is not the case. The exploitation of militarism, nationalism, racism and sexism have always figured prominently in the arsenal of US capital. What we are seeing now is a qualitative intensification of this traditional policy, articulated within a new and dangerous restructuring plan, which proposes to dismantle the gains won by the workingclass and oppressed people in the last fifty years of struggle, at the same time that it is reasserting US imperialism’s hegemonic role in the international order.

Either capital’s austerity offensive (restructuring/ dismantling) can be carried out by the power bloc through mechanisms of bourgeois democracy, or this state form has reached its limits and monopoly capital requires fascism for its rule to continue. It appears to us that authoritarian statism provides the means to readjust bourgeois democracy to new policies and still maintain hegemony over the workingclass and the middle strata. Let us measure the degree of development of the factors which would contribute to the rise of fascism in the present situation to assess the extent to which conditions favoring a rise of fascism are maturing.

(1) At the level of the power bloc it appears that capital is divided over just how far and how fast to proceed with dismantling the governmental system which is the legacy of the New Deal. Considerable differences also exist on the nature and appropriate forms that aggressive foreign policy decisions should take: in regard to the Soviet Union, to the national liberation struggles, and to other imperialist rivals. All of these differences have been highlighted in the recent struggles between Democrats and Republicans, within the Republican Party itself and even within Reagan’s own staff over such issues as the Kemp-Roth tax-cutting plan, aid to El Salvador, and Salt II and detente.

Even with these divisions there is no indication that there exist basic structural obstacles to the working out of these differences which would require the abandonment of bourgeois democracy in favor of fascism. All significant sections of the power bloc have an objective interest in some kind of restructuring as a capitalist solution to the crisis; where they differ is on the best way to accomplish this goal.

(2) At the level of the petty bourgeoisie and the middle strata there has not been a significant detachment of these forces from the Democratic and Republican parties that they have traditionally supported. In fact the ability of the Republican Party to absorb the forces who have polarized to the right has been matched by the ability of the Democratic Party (through Kennedy, DSOC and others) to retain those who have become disenchanted with the two parties from the left.

This is illustrated by the limited character of the Anderson campaign, which did not constitute a real break from the two-party system, and the poor electoral showing of the Libertarian and Citizens parties, all of which demonstrate how strong the hegemony of the two major parties continues to be, and with them, the strength of bourgeois democracy itself.

(3) At the level of the workingclass, fascism becomes a serious possibility when bourgeois democracy is no longer capable of absorbing or neutralizing their activities and struggles to constitute an alternative pole of hegemony. In the United States today the activity and consciousness of the workers and oppressed people has not developed to the extent that this situation exists, or will reasonably exist in the foreseeable future. Neither the AFL-CIO bureaucracy, nor the Social Democratic labor left (Winpisinger and Fraser) are leading the workers anywhere except to a halfhearted battle against the austerity offensive, as the recent Chrysler settlement with UAW shows. The spontaneity and combativeness of the US workingclass should not be discounted, but without consciousness of purpose, clearsighted leaders and new forms of organized struggle, the immediate future shows no sign of a radical departure from traditional practice.

In short, all factors point to the conclusion that the conditions favoring the rise of fascism as the political movement of capital have not matured. This does not mean of course that the conditions favoring the rise of fascist organizations such as the KKK, Nazis, etc., do not exist. As we noted above, they are a constant presence under advanced capitalism and their ranks are certainly increasing as a result of the present crisis.

This danger of fascism is very real and requires urgent attention. While it would be an error to see these groups as the simple instruments of capital, it is an equally serious error to ignore the extent to which sections of the state apparatus have acquiesced to the growth and activity of these groups and even encouraged them. This is not because, as the “ultra-left” alleges, monopoly must have fascism and keeps such groups waiting in the wings until they are needed, but because they play a definite role in the disorienting and dividing of people to the advantage of capital. The struggle against these fascist groups is always important, whatever our primary strategy turns out to be.

A number of leading forces within the Leninist left who argue that the policies of the Reagan government represent a rise of fascism, have logically put forward the United Front Against Fascism as the appropriate strategic response for the entire left to adopt. Or rather, we should say that these forces, having adopted the united front against fascism strategy, have derived from it the prospect of a rising fascist danger.

In any case it would seem that those who put forward this view would critically study and struggle over the theory and practice of the United/Popular Front strategy in the 1930s to determine its strengths and weaknesses, contributions and errors. But the dogmatic repetition of official texts is always easier than the study of real history. Unfortunately, a Dimitrov quote from 1935 is a very poor substitute for the concrete examination of how that quote was practiced in 1936, 1937 and 1938.

If the principal motion of the United States today appeared to be in the direction of fascism, it would be our responsibility to seriously examine and resolve a number of historical problems associated with the United/Popular Front line of the 1930s before we could confidently attempt to practice it in contemporary conditions. Problems such as:

(1) To what extent is the United Front Against Fascism strategy a general and universal one, and to what extent is it specific to countries moving in the direction of fascism? Was the Comintern’s universal application of it correct or not?

(2) Is Dimitrov’s definition of fascism, which was an important theoretical basis of the strategy, correct? Did it unnecessarily narrow the class base of fascism? Is it adequate for dealing with contemporary fascism? Can it be improved in the light of contemporary Marxist studies?

(3) Did the practice of the Popular Front lines in France, Spain, the United States and elsewhere lead to an expansion of proletarian influence, or its subordination to the bourgeoisie, class collaboration etc.? Were the errors which were made in this period a result of the line itself, or deviations from it?

(4) To what extent did the United/Popular Front line encourage the growth of bourgeois nationalism in the Communist Parties?

(5) To what extent is the “united front against monopoly” (antimonopoly coalition) line of modern revisionism a direct descendant of the United Front Against Fascism line, modified for conditions in the post-World War II world?

(6) In what respects was the post-1935 United Front line similar to that proposed by Lenin in 1921? In what respects was it different?

If our main strategic concern were fascism, we would have to look into all of these problems, which have been noted by too many serious Marxists to be simply dismissed or ignored. However, since we at the Theoretical Review have concluded that the primary direction of development of US capitalism is not towards fascism, we see the need for an alternative strategy.

An alternative strategy[22] is necessary because the United States is not moving toward fascism at the present moment, nor are the increased racism and militarism signs of a turn to fascism on the part of the ruling class. The view that fascism is an immediate threat is fundamentally ultra-left in character and must be rejected. What we are witnessing instead is the development of a new stage in the history of world capitalism which requires new theoretical, political and strategic approaches.

Not ancient dogmas imposed on a reality which rejects them, but a concrete analysis of a new, concrete situation is essential. A nationally organized and coordinated investigation of the trends and contradictions of this unfolding process therefore becomes imperative, since no one group has sufficient forces or national resources to undertake it alone. Naturally, simple study is not enough: equally necessary is actual participation in this process–in the emerging struggles and mobilizations of the workers and oppressed peoples which are beginning to build.

Based on the results of these studies and our involvement in the events themselves we can begin, together with other left and progressive forces, to develop an alternative strategy against capital.

While we are convinced that the specific form and features of this alternative strategy awaits a national investigation, we feel confident that its general character can begin to be sketched out. Our own initial summation of its general features is as follows.

American imperialism is facing a structural crisis of capital accumulation. Because this system has not reached the limits of its development[23], the present crisis can be resolved within the limits of capitalist relations of production. For that reason, and because a revolutionary situation does not exist, the crisis is, for the moment, proceeding by way of restructuring of social relations under the ultimate hegemony of the existing ruling class.

The general framework within which restructuring is now taking place has assumed the form of an economic austerity offensive coupled with a dismantling of Keynsian governmental services; the political development of authoritarian statism, and an across-the-board ideological offensive based on the exploitation of racism, sexism and anti-communism. While this is the current direction restructuring is taking, it is by no means the only form of restructuring available. Historically, a structural crisis of this type has lasted for ten or twenty years. Whatever the ultimate form (or forms) of restructuring will be, depends in the last instance, upon the class struggle.

For this reason, left intervention in, and organization of mass struggles can play an important role in shaping the direction that restructuring will take. This is why we would formulate the general strategic tasks of the present period as follows: (a) to organize mass resistance to the current restructuring process; (b) to wrest whatever concessions are possible out of this confrontation; and (c) to ultimately force an alternative restructuring program, one more favorable to the interests of the workingclass and oppressed peoples. Let us look at each feature of this strategy in more detail.

Capital’s program necessitates a certain degree of popular support, or at least acquiescence, in order to be implemented. Currently the state is actively trying to convince the people to tighten their belts at the same time that the most favorable conditions are being provided to big business. Because a central part of this campaign is the effort to ideologically disorient people, and put the blame for the crisis on foreigners, minorities, the poor and the left, it is imperative that the most vigorous campaign be initiated to defeat racism, bourgeois nationalism, sexism and anti-communism as an essential component of the effort to overcome popular disunity and the divisions within the workingclass.

Other organized activities which would block the smooth implementation of the present policy include the following: disruption of the dismantling of needed social services and related government programs; mobilization of workers to reject national chauvinist “buy American” campaigns and to resist wage reductions, unemployment, and plant closings; community organizing to resist the further deterioration of urban life; revival of the anti-draft and anti-war movements; etc. Naturally, many of these struggles will emerge spontaneously, as they have already. The role of the left is to provide then a more organized character and a higher consciousness, but most importantly, it is to link all of these struggles together and to give them a strategic vision as to what they can accomplish beyond their own particular goals. Mass resistance is the defensive aspect of the alternative strategy.

In a restructuring crisis which lasts for many years, capital can sometimes be forced by social and class struggles to grant concessions in the shape of reforms. Some of the reasons for acceding to these reforms are as follows:

(1) to maintain the legitimacy of the existing economic and political order; (2) to maintain social peace and a certain ideological consensus; (3) to come to terms with the economic power of the workers and their unions; and the social power of other groups through their mass organizations and communities; (4) out of recognition that certain reforms are necessary as part of the restructuring (the economic benefits for capital provided by Keynsianism, in the 1930s for example).

The obligation of Communists with regard to these reform struggles is to determine just what kinds of reforms are historically necessary and conjuncturally possible, and to organize the most effective movement to win them. The Communist Party championed necessary and possible economic reforms during the Depression such as unemployment insurance and social security, but failed to do the same in terms of fighting for political concessions. Today the left needs to go beyond abstract talk about revolution and to develop a concrete program of necessary and possible reforms which can be fought for and won, in a revolutionary manner, within the context of the present crisis. Only such a concrete program of realizable reforms will enable us to break out of our sectarian isolation and build real ties with popular struggles. Forcing concessions is the offensive aspect of the alternative strategy.

If the masses do not actively intervene in the restructuring process with their own agenda, it will necessarily proceed in a way most favorable to capital. If, however, popular resistance can halt or sufficiently slow down capital’s favored restructuring, then the possibility exists that this resistance, coupled with other contradictions and divisions within the power bloc itself, can force on capital an alternative program, more favorable to the people. An historical antecedent of this turn of events is the replacement of Hoover’s austerity offensive by Roosevelt’s New Deal. In that case Monopoly did not relinquish its hegemony, it was only forced to proceed through different means, relying more heavily on concessions and policies whose objective effect was to create better conditions for mass struggle (acceptance of industrial unionism, government social programs, etc.).

Today the left cannot sit on the sidelines refusing to fight for a more progressive restructuring, simply because this goal falls short of revolution. The struggle for reforms cannot be abandoned; it must be taken up in a revolutionary manner. So too with the class battle over restructuring. If successfully conducted it can create more favorable conditions for an eventual revolutionary situation and prepare the masses for that “final conflict.” When discussing alternatives to the present reactionary restructuring we must be careful to realistically assess what are the most likely alternatives and not simply the ones we would like to see implemented.

In the present context a more progressive restructuring of US society would most likely proceed by way of some form of governmental nationalization along the lines of British Laborism or the more conservative European Social Democratic Parties, which would enjoy the support of sections of capital, the middle strata and the workingclass. This is only a guess; any actual alternative will probably represent a combination of contradictory features. The important thing to recognize is that alternatives exist and the workingclass cannot remain indifferent to them; exploiting the contradictions of the present crisis to its own advantage is essential to improving its ability to confront capital in the post-crisis period, and for preparing the workingclass to consolidate and lead a national-popular bloc of anti-capitalist forces.

The challenge for the left is to provide a strategy and aid in the popular mobilization for a more progressive restructuring while maintaining its independence and critical facilities. There is little argument that Reagan’s policies will not work. If they are eventually defeated and the Democrats come to power on a more liberal program, we must be prepared for a shift in strategy and tactics. We cannot afford to get swept along as the left-wing tail of a progressive restructuring the way the Communist Party, USA was carried along behind the New Deal. With a clear conception of the nature of the restructuring process and the heterogeneous class forces which can be mobilized behind different approaches to it, we will be prepared to fight for the long-term interests of working and oppressed people regardless of the direction which US capitalism takes. This is the long-term aspect of the alternative strategy.

What we have written here is only a first and tentative expression of our thinking on the question of strategy. It is being issued now to contribute to the debate currently unfolding on the left in regard to this question. We look forward to discussing and debating it with others.

[1] See The Way Out. Manifestos and Resolutions of the 8th Convention of the CPUSA (Workers Library, 1934).

[2] See “Leninist Politics and the Struggle Against Economism,” in Theoretical Review, No. 15.

[3] On the exceptional state see Poulantzas, Fascism and Dictatorship (NLB, 1974), Part 7.

[4] The Way Out. Also, Earl Browder’s Communism in the United States.

[5] Earl Browder, Fighting for Peace, (International, 1939), pp. V, 144-45.

[6] See the articles which appeared in the newspaper Workers’ Age by August Thalheimer, immediately following the Seventh Congress.

[7] See Jay Lovestone, The People’s Front Illusion, (Workers Age, n.d.).

[8] Fighting for Peace, p. 147.

[9] In addition to Irene North’s article in this issue, see Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, Poor People’s Movements (Vintage, 1979), Ch. 2.

[10] “A Fundamental Critique of the Communist Party of France,” in Theoretical Review, No. 6, p. 35.

[11] Communism in the United States, pp. 89 & 71.

[12] On the problem of desertion see Henry Winston, “Gear the Party for its Great Tasks, Political Affairs (Feb. 1951), pp. 43-46.