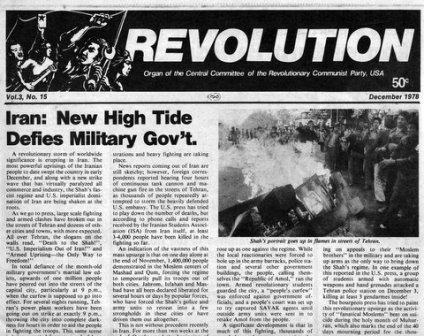

First Published: Revolution, Vol. 3, No. 15, December 1978.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

With every passing day, the revisionist rulers of China are stepping up the tempo of their attacks on Mao Tsetung and the revolutionary line that Mao stood for and fought for all his life. Article after article in the press stresses that Mao must not be seen as a “god,” that Mao Tsetung Thought must not be regarded as “dogma,” and a flurry of officially tolerated wall posters claim that he made “mistakes,” especially in the later years of his life. This is a necessity for them because Mao’s line–especially as it developed through the Cultural Revolution–does in fact pose a mortal danger to their revisionist line and to the all-out drive they have launched to dismantle socialism and restore capitalism.

A crucial part of these attacks on Mao and the Chinese revolution is building up Chou En-lai as a great national hero, and in fact raising him above Mao in stature as a model “communist” to be emulated for the “new historical mission” of modernizing China by the year 2000. As Peking Review 47 recently gushed, “The people highly respected and loved him, and pinned their hopes on him for realizing the lofty ideal of the four modernizations and making their motherland strong and prosperous.”

While the second anniversary of Mao’s death in September 1978 rated less space in Peking Review than an article calling for achieving world levels in textile production, there has been a steady stream of articles heaping mountains of praise on Chou En-lai and insisting (correctly) on the close ties between him and the current rulers. A major 14-page article appeared in Peking Review in January, 1977 on the first anniversary of Chou’s death, followed by articles throughout 1977 and 1978 on his great achievements during the Cultural Revolution, in foreign policy, and “his personification of the Party’s style of work.” The latest, and perhaps most revealing, of these articles is part of a speech given by Chou En-lai himself in 1949 to the First All-China Youth Conference titled, “Learn from Mao Tsetung.” This is given front page billing in PR 43 of this year.

In this speech Chou warns the youth not to view Mao as a “godhead” and devotes considerable effort to explaining how Mao was superstitious and had many backward ideas when he was young, and that he of course made mistakes. Though no one can be free of making mistakes and Mao frequently pointed to his own, the current rulers are clearly using this speech to throw open the door for criticizing and attacking Mao’s line as a whole.

Chou says that Mao did not accept the advice of a Comrade Yun Tai-ying to start doing work in the countryside in the mid-1920s since he was “preoccupied with work in the cities”; under present conditions the effect of this is to throw in doubt the fact the Mao did lead the Chinese Communist Party in developing and carrying out the strategy of encircling the cities from the countryside and by implication to question Mao’s role in the socialist stage of the revolution as well.

Furthermore, nowhere in this speech does Chou En-lai explain that he himself went along with the “left” lines in the late 1920s and early 1930s that caused serious losses to the Party and the Chinese revolution, and which Mao had to struggle against and defeat in order for a correct line to win out in the Party. Chou did not throw his support firmly behind Mao’s line until the critical Tsunyi Party conference in January, 1935 during the beginning of the Long March.

This speech also fits in neatly with the revisionists’ present approach of downgrading Mao to being an important leader, yes, but just one of the many veteran leaders of the Chinese revolution. (This is the none-too-subtle message of a 1955 picture reprinted with Chou En-lai’s speech, which has obviously been cropped to place Chou in the center, with Mao on his right and Chu Teh on his left.)

According to the present rulers, Mao was all right before 1949 but became increasingly out of touch with the “new tasks” of the revolution–to the point of making the big “mistake” of launching and leading the Chinese people in waging the. Cultural Revolution and allowing himself to be “misled” by the “gang of four.” Immediately after they pulled off their counter-revolutionary coup d’etat in 1976 the revisionists went to great lengths to place Mao in opposition to his four closest comrades, the so-called “gang of four,” in order to sow confusion among the masses and consolidate their power. (This was especially true of the revisionist forces grouped around Hua Kuo-feng, whose positions and authority rest heavily on Mao’s supposed “behests.”) Now, they are saying all but openly that the “gang of four” was in fact a “Gang of Five.”

Thus it is not surprising that the latest correct verdict to be reversed and the most open attack on Mao to date concerns the large-scale riot staged by counter-revolutionaries at Tien An Men Square in Peking on April 5, 1976. Claiming that lack of respect was being paid to Chou En-lai (who had died a few months earlier), they directly attacked Mao and those in Party leadership who stood with him and loudly declared their support for Teng Hsaio-ping’s attempts to carry out Chou’s revisionist program for “modernizing” China and reversing the Chinese revolution. Overturning and burning cars and physically attacking the people’s militia units, they raised the cry: “We spill our blood in memory of the hero [Chou En-lai]; raising our brows we unsheathe our swords. China is no longer the China of yore, and the people are no longer wrapped in sheer ignorance; gone for good is Chin Shih Huang’s feudal society [meaning the rule of the working class under Mao’s leadership].”

Though this reactionary riot was put down by the people’s armed forces and Teng was dismissed from all his posts in the Party because of his role in instigating the riot, it did serve as a signal to the Rightist forces to step up their counter-revolutionary activities, and it also made clear who their overall leader had been and who remained their rallying point even in death–Chou En-lai.

In the middle of November, 1978, the Peking Party leadership described these reactionary riots as “completely revolutionary” (PR 47). Numerous articles in the papers and even a new film lauded “The Heroes of Tien An Men Square.” At the same time, wall posters appeared in Peking, clearly with the approval of the Party leadership, attacking Mao directly. One 14-page poster, prominently displayed in the middle of Peking, stated: “Because Chairman Mao’s thought was metaphysical in the last years of his life and for all sorts of other reasons he supported the four in getting rid of Teng Hsiao-ping.” The poster went on to say, “After Tienanmen, the four made use of Chairman Mao’s errors of judgment concerning the class struggle and capitalized from the situation to launch a general offensive against the cause of revolution in China.”

In Peking Review 46, the revisionists emphasize that by, the time of the Tien An Men incident, “the attitude towards Comrade Chou En-lai had become a touchstone for distinguishing revolution from counterrevolution and genuine Marxism from sham Marxism.” And indeed it had, for by the beginning of the 1970s Chou En-lai had developed into the overall leader and main rallying point for the Right–especially the capitalist roaders headquartered in the Party–in direct opposition to the proletarian revolutionary headquarters led by Mao and with the Four as its active core.

Chou En-lai was one of the chief representatives of an entire layer of veteran Party officials and leaders who had supported the democratic revolution but failed to advance and became counter-revolutionaries, capitalist roaders, in the socialist stage, especially the farther the socialist revolution advanced and the deeper it struck at the vestiges and inequalities left over from the old society. It was exactly about such people that Mao explained,

After the democratic revolution the workers and the poor and lower-middle peasants did not stand still, they want revolution. On the other hand, a number of Party members do not want to go forward; some have moved backward and opposed the revolution. Why? Because they have become high officials and want to protect the interests of the high officials.

As Mao stressed many times, the development of people, particularly leading Party members, from bourgeois democrats into capitalist-roaders was a big phenomenon in the Chinese revolution. Since in China the struggle passed through a long stage of bourgeois-democratic revolution, though of a new type, led by the proletariat and the Communist Party, many people hitched their wagon onto the Chinese Communist Party without making a radical rupture with bourgeois ideology and taking up the revolutionary outlook of the proletariat. For these bourgeois democrats, the goal of the revolution was to overcome China’s backwardness and the near total strangulation of China by the imperialist powers. Therefore they turned to “socialism”–public ownership–as the most efficient and rapid means of turning China into a highly industrialized, modern country. As the socialist revolution advanced, they fought for this development to take place along increasingly bourgeois lines–which under China’s conditions would not only restore capitalism but would also lead to bringing China back under the domination of one imperialist power or another.

As early as 1964, Mao said that the main target of the socialist revolution had become “those Party persons in power taking the capitalist road.” In 1976 Mao laid great emphasis on a correct understanding of this question. He pointed out:

With the socialist revolution they themselves come under fire. At the time of the co-operative transformation of agriculture there were people in the Party who opposed it, and when it comes to criticizing bourgeois right, they resent it. You are making the socialist revolution, and yet don’t know where the bourgeoisie is. It is right in the Communist Party–those in power taking the capitalist road.

To make it clear that this was a life-and-death struggle over which class would rule China, the proletariat or the bourgeoisie, Mao concluded, “The capitalist roaders are still on the capitalist road.” This and many other statements by Mao were directed not only against Teng Hsiao-ping (about whom Mao also said “he represents the bourgeoisie” and that he made “no distinction between imperialism and Marxism”) but against other capitalist-roaders, including Chou En-lai himself–who had served as the chief mentor of the Right. This was widely known inside China and amply demonstrated by his all-out campaign to rehabilitate unrepentant capitalist roaders such as Teng Hsaio-ping who had been knocked down in the Cultural Revolution and to promote both them and their revisionist program to the highest levels of government (for instance, Teng was groomed and handpicked by Chou to be acting premier when his health deteriorated during 1975).

Besides being chosen to downgrade and attack Mao, Chou En-lai’s 1949 speech “Learn from Mao Tsetung” reveals a great deal about Chou’s political line and bourgeois-democratic world outlook at that time. The most striking feature of Chou’s speech, delivered in May, 1949–when countrywide liberation was both certain and imminent–is that it does not deal with the upcoming socialist stage of the revolution at all. It makes but one token reference at the end to “make preparations for the shift to a socialist New China” as just one of the many questions confronting youth.

This is exactly the viewpoint of the bourgeois democrats in China who could not see beyond defeating the “three great mountains” of imperialism, feudalism and bureaucrat-capitalism, and for whom the main task lying ahead was hard, practical work in building China into a great, modern country. As demonstrated repeatedly over the course of the next two decades and more, this kind of outlook would feed directly into the revisionist line that the role of the masses is to put their noses to the grindstone and leave politics and affairs of state to the veteran leaders and high officials.

On the question of pushing the revolution forward, Chou repeatedly emphasizes that it is necessary to “wait and do some persuading.” His emphasis is not on mobilizing the masses and relying on their conscious activism to advance the revolution. Chou’s message is to go slow–the democratic revolution will be a long period, and only when we have united “the great majority” will it be opportune to start talking about the socialist revolution. Using the demagogic line of a bourgeois democrat, Chou argues that “when the great majority do not agree, we must follow the majority organizationally.”

Furthermore, just as Chou claims that, in terms of struggle within the ranks of the Party, “the War of Liberation has been plain sailing, more or less,” he apparently expects smooth sailing in the future. Concerning the development of erroneous lines Chou states that “the possibility of such situations occurring in future work will be reduced.” There isn’t even the slightest glimmer of understanding here that class struggle continues under socialism.

On this question of how to view the new revolutionary tasks confronting the Chinese people in 1949, there is a world of difference between Mao’s and Chou’s political outlook–the difference between a proletarian revolutionary and a bourgeois democrat. Throughout the various stages of the new-democratic revolutionary struggle, Mao constantly stressed the need for the Party to keep its sights set on the socialist revolution and eventually communism lying ahead, exactly because of the overwhelming spontaneous tendency and great danger of identifying the ideology of the Party with the immediate democratic stage of the revolution. In early 1949, Mao explicitly pointed out that the principal internal contradiction after the liberation of China would become “the contradiction between the working class and the bourgeoisie.”

Though Mao could not then predict the actual form that the class struggle would take in the future as the socialist revolution advanced and deepened, his whole approach was based firmly on materialist dialectics and called on the masses and Party members to “cast away illusions, prepare for struggle.”

At an important Party CC meeting held in March 1949, at roughly the same time as Chou’s speech, Mao warned that

After the enemies with guns have been wiped out, there will still be enemies without guns; they are bound to struggle desperately against us; we must never regard these enemies lightly. If we do not now raise and understand the problem in this way, we shall commit very grave mistakes.

Later in this same report, Mao made his famous statement that

There may be some Communists, who were not conquered by enemies with guns and were worthy of the name of heroes for standing up to these enemies, but who cannot withstand sugar-coated bullets; they will be defeated by sugar-coated bullets. We must guard against such a situation. To win country-wide victory is only the first step in a long march of ten thousand li. (Mao, Selected Works, Vol. 4, p. 374.)

Two months later, Chou’s speech referred only to the last part of Mao’s statement “To win country-wide victory...” and explicitly tied it to more “difficult and arduous work,” completely divorcing it from the continuing class struggle.

In this same report Mao blasted people, both inside and outside the Party, who were arguing for working out a deal with U.S. imperialism, even though it had armed Chiang Kai-shek to the teeth and was still intent on strangling and dominating China. According to them, on its own, and even with assistance from the Soviet Union, China could not develop its economy. Mao argued back that by relying on the masses of Chinese people and first and foremost the working class, and with the support of the working class of the countries of the world and chiefly the socialist USSR, “there is absolutely no ground for pessimism about China’s economic resurgence.”

As for accusations that the Party was leaning too heavily towards the Soviet Union, Mao replied, “all Chinese without exception must lean either to the side of imperialism or to the side of socialism. Sitting on the fence will not do, nor is there a third road.” Then as well as now this statement of Mao’s exposes a consistent feature of the revisionists in China–their “leaning” and ultimately their falling completely over backward into the clutches of one or the other bloc of imperialist countries.

Such people, Mao pointed out, were like the bourgeois democrats of the turn of the century who always looked to the imperialist West and its model of capitalist modernization for China’s salvation. In opposition to this Mao said that China would and must take the socialist road–“only socialism can save China,” as he was to repeatedly insist. This was a direct rebuke to people like Chou, whose line not only would not lead the struggle forward to socialism but would not even succeed in accomplishing the democratic and anti-imperialist tasks of the revolution, just as the line of Chou and his counterrevolutionary successors is leading to China once again becoming a feasting ground for imperialist vultures.

It is significant to note here that the U.S. government recently released an alleged memorandum kept secret for almost 30 years that in June of 1949 Chou En-lai made a secret overture to the U.S. government through a third party, saying that he (Chou) represented a “liberal” faction within the Chinese Communist Party that wanted to be “independent” of the Soviet Union, and requesting U.S. aid to develop the economy, which Chou reportedly saw on the brink of collapse. This report needs to be investigated further, but such an overture is consistent with the policies of Chou’s that showed up repeatedly in the following years–most graphically with his championing, in the early 1970s, together with Teng Hsiao-ping, of the strategic “Three Worlds” line of capitulating to and relying on the Western imperialist countries in order to obtain the technology and capital necessary to “modernize” China on a capitalist basis.

Chou’s speech to this important Youth Conference in 1949 also literally reeks with a totally perverted conception of the relation between leaders and the masses. In the first paragraph of what is reprinted of this speech, Chou says: “We must have a leader accepted by all of us, for such a leader will lead us in our march forward” (PR 43, p. 7; emphasis added), and he later claims that the Party will not have as much two-line struggle in the future because “the overwhelming majority of our comrades accept him [Mao] as our leader and have real faith in him; moreover, he enjoys the support of the people.” (p. 12) In other words, his conception is that the role of a leader is to get himself “accepted” by everyone, and now that we have a leader with such universal acceptance, we won’t be bothered with these problems of two-line struggle like we used to be. This is indeed a good picture of how Chou functioned–trying to win universal acceptance and avoiding open two-line struggle like the plague–but it is thousands of miles removed from the way of functioning of a real communist leader like Mao Tsetung.

Very significant is the fact that, in exhorting the youth to “learn from Mao Tsetung,” Chou chooses to stress two things: (1) that Mao applies Marxism-Leninism concretely, in the particular situation of China, and (2) that it is always necessary to “win over the great majority” before anything can be done. Why, in allegedly explaining Mao Tsetung Thought does Chou lay all his stress on these, and only these? Although he “modestly” notes that “what I have said is only a very small part of Mao Tsetung Thought” (p. 14), the effect of his speech is to reduce Mao Tsetung Thought to a pedestrian pablum of keeping your eyes on the concrete and patiently persuading the great majority before attempting to take any action. The vanguard role of communists is perverted into the role of condescending saviors or Confucian sages who patiently keep dispensing their pearls of wisdom until the backward masses finally wake up and pick them up. Throughout, Chou throws his whole emphasis on practice as opposed to theory, on the immediate over the long-range, on “facts” as against theoretical understanding of the essence, on the new-democratic and not the socialist, etc. His line is thoroughly rightist.

Chou constantly warns the youth against being superficial, arrogant and rash; but this is really the height of hypocrisy coming from Chou En-lai. “I too was rash in the past,” admits Chou in a show of false modesty. He continues, “Of course, it is not easy for the younger generation to acquire these good qualities.” (Ibid., p. 14.)

In contrast, Mao directed his criticisms of arrogance chiefly at those veteran leaders who thought that since they had made contributions to the revolution they deserved special treatment and could rest on their laurels.

In 1939, Mao gave a well-known speech in Yenan on the 20th anniversary of the May 4th Movement titled, “The Orientation of the Youth Movement.” He asked, “How should we judge whether a youth is revolutionary? How can we tell? There can be only one criterion, namely, whether or not he is willing to integrate himself with the broad masses of workers and peasants and does so in practice.” (SW, Vol. 2, p. 246.) This is what Mao emphasized and this is what Chou “forgets” to mention. (And naturally this is one of the features of Chou’s speech that the current revisionist rulers must find particularly appealing for realizing their plans of bringing up a new generation of “talented youth” that will spearhead the “four modernizations.”)

While Mao recognized that youth lacked experience, he emphasized that “In a way they have played a vanguard role–a fact recognized by everybody except the die-hards.” (Ibid., p. 245.) From Chou’s all-knowing lecture to these youth gathered in Peking in June, 1949, how could they ever “take the lead and march in the forefront of the revolutionary ranks”–as Mao called on China’s youth to do in 1939. In later years, Mao extended his thinking on the role of youth to point out explicitly that unleashing the daring and rebelliousness of youth was crucial to continue transforming and revolutionizing society and deepening the socialist revolution. Chou’s admonition to the youth is to emulate great individuals like Mao, work hard, and “be careful and conscientious and make as few mistakes as possible.” (PR 43, p. 14.)

Thoughout Chou En-lai’s speech Mao Tsetung Thought is reduced in substance to “new-democratic thought” and is gutted of its revolutionary content and essence, and the Mao that Chou calls on the youth to “learn from” is presented as a common liberal and a “practical-minded” communist. Chou portrays Mao as Chou saw himself–that of a wise man who has gained possession of the “truth of Marxism-Leninism,” and with this accomplished is solely concerned with the problems of implementation. As Chou himself repeatedly emphasizes, “the principles you have worked out must be put into concrete terms,” “Chairman Mao does not engage in empty talk but truth,” etc.

This is precisely the kind of pragmatic “communist” that Chou En-lai represented–and why he stands as a model to emulate for the new revisionist rulers of China. Mao in fact did stress practice and linking theory with practice, but what he stressed was linking revolutionary theory with revolutionary practice. Mao’s whole philosophical outlook stressed dialectics, that contradiction, the unity and struggle of opposites, was the motive force in the universe; he applied materialist dialectics to studying society and on that basis transforming the world through struggle. Mao criticized the “vulgar practical men” who “respect experience but despise theory, and therefore cannot have a comprehensive view of an entire objective process, lack clear direction and long-range perspective, and are complacent over occasional successes and glimpses of the truth. If such people direct a revolution they will lead it up a blind alley.” (“On Practice,” SW, Vol. 1, p. 303.)

Chou’s attempt to paint Mao as a “get things done” man is closely linked to picturing Mao as a democratic-minded liberal who was quite willing to let all viewpoints contend while he “waited and did some persuading” until the majority eventually came around to his viewpoint. But this again completely reverses Mao’s role as a tireless and implacable foe of every kind of revisionism and opportunism. Throughout the course of the Chinese revolution, from the mountains of Chinkang in the late 1920s to the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s, and the Cultural Revolution in the ’60s and ’70s, Mao very often found himself in a minority among his old comrades, who were almost all veterans of the war of liberation. What characterized Mao was that he never stopped struggling against incorrect lines and that he had confidence, based on a deep understanding of the laws of society and the class struggle, that the masses of people were fully capable of grasping a revolutionary line and transforming the world.

Chou’s liberalism also comes out in his claim that too many people were being executed–which was certainly not Mao’s line when, in 1949, the PLA was liberating vast amounts of territory and the masses of workers and peasants were settling scores with the tyrants and oppressors who had ridden on their backs for so long. Mao pointed out that without suppressing counter-revolutionaries, and executing those of them who had committed serious crimes against the people, the masses of people would not fully stand up. This was a point Mao stressed repeatedly during the early ’50s and the movement to suppress counterrevolutionaries.

The revisionist rulers obviously think that reprinting such a speech by Chou En-lai will build him up–and themselves, by association–in revolutionary stature. However, what it really does is provide a clearer picture of Chou’s bourgeois-democratic outlook on the eve of liberation in 1949, which is all the more valuable since Chou did not write very much (a typical trait of many pragmatic “communists” whose “principles” must change rapidly as conditions require).

In a major article that lavishly praises Chou En-lai’s contributions to the Chinese revolution, written by the State Council’s theoretical group in early 1977, the revisionists claim that “Premier Chou always attached importance to uniting with, educating and remoulding the intellectuals.” As evidence they explicitly refer to a special conference on the question of the intellectuals called by the Party Central Committee in 1956 where “Premier Chou made an important report which played a significant role in promoting the ideological remoulding of intellectuals and mobilizing their enthusiasm for socialism.” (PR 3, 1977, p. 15.)

However, if we look at Chou’s actual report (which was translated by the U.S. government after its release by New China News Agency in 1956), we find that its line is the exact opposite of this. While paying lip service to remolding the intellectuals, it seriously downgrades the importance of this task and completely divorces it from the continuing class struggle under socialism, as well as from the intellectuals integrating themselves with and learning from the workers and peasants; it openly caters to the intellectuals’ “ambition for advancement” and calls for providing them with more pay, privileges and “respect”; and it puts forward the revisionist view that science and technique, and the “highly trained intellectuals” necessary to wield them, occupy the central role in the construction of socialism.

There is good reason for the current Chinese rulers to promote this report of Chou En-lai’s, for it puts forward fundamentally and in many specific aspects the same revisionist line on the question of intellectuals and science and technology which they are presently putting into practice with a vengeance. Mao’s speeches on the same questions during 1956-57 and, even more pointedly in future years, stand in fundamental opposition to Chou’s line.

Here it must be pointed out that the task of carrying out economic construction along the socialist road in China–an economically backward country with a legacy of imperialist domination and feudal stagnation–has been a crucial question for the Chinese Communist Party. Especially right after 1949 there was a need to rely on intellectuals, technical “experts,” even industrial managers–all of whom had been trained in the old society and enjoyed a great deal of privilege over the masses of working people, who had been maintained in illiteracy and had been barred from this kind of knowledge under the division of labor in the old society. This necessity of relying to some degree on the intellectuals, whose outlook was still largely bourgeois, inevitably strengthened bourgeois influences and bourgeois forces in society and within the Party as well.

Mao recognized the necessity of uniting with and utilizing many intellectuals–especially in the mid-’50s, when China was coming into increasingly sharp conflict with the Soviet Union and the need to quickly train and utilize large numbers of Chinese intellectuals was becoming more urgent to decrease dependence on the Soviets. However, Mao insisted that the intellectuals must be remolded in their thinking and must take part in productive labor and political struggle together with the masses. Mao repeatedly emphasized at this very time that without such ideological remolding the intellectuals would turn into a dangerous force for reaction because of their strategic positions and influence in society.

This sweeping view of Mao’s–that of a proletarian revolutionary–is completely absent from Chou’s report. For Chou the fundamental question is that certain sectarian errors in dealing with the intellectuals, “the most valuable assets of the state,” are preventing them from fully contributing to the task of socialist construction. Other than the, task of “weeding out” the few remaining counter-revolutionaries and bi elements, the class struggle is not a critical question anymore, according to Chou. Instead of warning Party members and intellectuals about the danger of the bourgeoisie’s sugar-coated bullets, Chou calls for more of such bullets and for making them as sweet possible.

Mao, on the other hand, presented the question in a fundamentally different manner. In “On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People” in early 1957, Mao recognized that the class struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie would be “protracted and tortuous and at times even very sharp.” Mao stated that

It will take a fairly long period of time to decide the issue in the ideological struggle between socialism and capitalism in our country. The reason is that the influence of the bourgeoisie and of the intellectuals who come from the old society, the very influence which constitutes their class ideology, will persist in our country for a long time. If this is not understood at all or is insufficiently understood, the gravest of mistakes will be made and the necessity of waging struggle in the ideological field will be ignored. (SW, Vol. 5, pp. 409-10.)

In order to downplay the importance of waging just such ideological struggle, Chou claims that “The overwhelming majority of the intellectuals have become government workers in the service of Socialism and are already part of the working class.”’ Among the “higher intellectuals,” about whom Chou is particularly concerned, he quotes statistics that say that 45% “actively support Socialism,” 40% support the government but are not “sufficiently progressive”, while the remaining are backward elements and counter-revolutionaries. With this in mind, Chou called for recruiting 1/3 of the higher intellectuals into the Party by 1962.

Mao had something to say on this question as well. In early 1957 he said that only 10°/o of the country’s five million intellectuals take “a firm stand–the stand of the proletariat.” As for the great majority, Mao classified them as “wavering.” They “still have a long way to go before they can completely replace the bourgeois world outlook with the proletarian world outlook.” While Mao supported recruiting political advanced intellectuals into the Party, he still noted that “even these Party intellectuals constantly waver and ’fear dragons ahead and tigers behind’” and he continued to emphasize making advanced workers and peasants the backbone of the Party. (“Speech at the Chinese Communist Party’s National Conference on Propaganda Work,” SW, Vol. 54, pp. 424-425)

And as for Chou’s statement that the intellectuals have joined the working class, Mao clearly states that they are part of the petty bourgeoisie, whose remolding “has only just started.” Not surprisingly, Chou’s line here is quite similar to that of Teng Hsiao-ping, who gave the report on the Constitution at the Party’s 8th National Congress in the fall of 1956. As part of his revisionist line that class struggle was dying out and rigid class distinctions no longer reflected China’s new situation, Teng argued that “The vast majority of our intellectuals have now come over politically to the side of the working class, and there is a rapid change in their family background. The conditions in which the city poor and the professional people used to exist as independent social strata have been virtually eliminated.”

As for Chou’s policies for reeducating the intellectuals, he calls for organizing more visits to socialist construction projects, working in their professions, and general theoretical study, which he emphasizes should not conflict with their “professional duties,” for which “at least five-sixths of the working day” must be reserved. Further, the cornerstone of Chou’s program for the intellectuals calls for catering to their “ambition for advancement”–which can only “educate” the intellectuals in a fundamentally bourgeois direction.

Just one year later, Mao called attention to the fact that “Among students and intellectuals there has recently been a falling off in ideological and political work, and some unhealthy tendencies have appeared. Some people seem to think that there is no longer any need to concern themselves with politics...” In his speech at the Party National Conference on Propaganda Work in March 1957, Mao referred to visiting an occasional factory or village as “looking at the flowers on horseback.” While calling this better than doing nothing at all, Mao advised more intellectuals to “settle down” among the workers and peasants and thoroughly remold their world outlook. For as Mao stressed, “In order to have a real grasp of Marxism, one must learn it not only from books, but chiefly through class struggle, through practical work and close contact with the masses of workers and peasants.” (SW, Vol. 5, pp. 426-27.)

For Chou, the fundamental question is how to “stimulate” the intellectuals to help build China into a great modern country. In an eclectic formulation that the current revisionist rulers constantly use, Chou’s solution is to combine political education with material rewards. Chou calls for giving them more pay and better living quarters, giving them the necessary assistants and “respect,” restoring titles and promotion systems–in short, the bottom line is to cut out all this crap about “politics” and unleash the intellectuals’ “ambition for advancement.”

Showing his Confucian tender loving care for their privileged position over the great majority of the people, Chou says that “in order to enable the higher intellectuals to devote greater energy to their work, their treatment should be appropriately raised. Some higher intellectuals have to spend unnecessarily much time over trifling matters in their living and this must be considered a loss of the state’s labour power.”

The intellectuals’, especially the “higher intellectuals’,” confidence in Chou’s concern for them is well rewarded:

First, we should tell the administrative personnel of all the departments concerned to regard the living conditions of the intellectuals as a matter of importance. Second, we should educate the trade union organizations in all the departments concerned and the consumers’ cooperatives to strive to expand their services for the benefit of the intellectuals. Third, we should make suitable adjustment in the salaries of intellectuals on the principle of remuneration according to work, so that their earnings are commensurate with their contribution to the state. The tendency of equalitarianism in the systems of remuneration and other irrational features should be eliminated.

And Chou notes another “irrational” feature of the treatment of intellectuals:

This irrational system of promotion greatly obstructs the ambition for advancement on the part of the intellectuals, and obstructs especially the fostering of new forces and the selection of intellectuals generally for better positions. This system must be rapidly revised. In addition, an important measure for the encouragement of intellectuals’ ambition for advancement and the stimulation of scientific and cultural progress is to be found in the conferment on intellectuals of degrees and titles... (emphasis added)

When Chou turns to the workers and peasants, immediately after this naked call to heap new privileges on the intellectuals, the ugly side of his Confucian “concern” for the people is revealed quite starkly:

we must carry out education among the workers, and let them understand how to correctly deal with intellectuals, so that their proper sense of self-respect may not be unwittingly impaired, since all righteous laborers be unwittingly impaired, since all righteous laborers should have self-respect.

In other words, Chou’s message to the workers is: “Learn your place and like it.” Like all revisionists who preach the dying out of the class struggle, this is strictly a one-way street. While they call on the masses to put an end to their struggle against the bourgeoisie and its reactionary ideology, they implement new ways to control and suppress the workers.

Not surprisingly, Chou’s program for the intellectuals, especially the highly trained intellectuals, reappears in all its revisionist splendor in the “Party CC Circular on Holding a National Science Conference,” prepared by Teng, Hua & Co. in September, 1977:

We must see to it that those scientists and technicians who have made achievements or who have great talent must be assured proper working conditions and provided with necessary assistants. Titles for technical personnel should be restored, the system to assess technical proficiency should be established and technical posts must entail specific responsibility. Just as we ensure the time for the workers and peasants to engage in productive labour, so scientific research workers must be given no less than five-sixths of their work hours each week for professional work. (Peking Review 40, 1977, p. 10.)

Chou’s line, echoed here by the current revisionist rulers, is exactly the Confucian doctrine of “restoring the rites” and completely in line with the Confucian–and generally the exploiting class–notion that those who work with their minds govern while those who work with their hands are governed. As Mao and other proletarian revolutionaries in the Chinese Communist Party were to point out repeatedly in the future, under socialism the question of how to deal with the inequalities and the bourgeois division of labor inherited from the old society, of whether to expand or restrict “bourgeois right,” becomes a critical dividing line for continuing the revolution or opposing it.

For several years before his death, Mao emphasized that the new socialist society is in many ways not much different from the old society, especially as regards inequality among the people, the mental-manual contradiction, worker-peasant differences, differences in rank and pay, etc. He analysed how the bourgeoisie emerges and draws its very lifeblood from the contradictions of socialist society itself and how the main danger comes from bourgeois headquarters that will repeatedly form in the Party itself to defend and expand these differences and inequalities and to protect and unleash a social base of more privileged strata. Building socialism and going onto communism, Mao showed, depends on unceasing class struggle against the bourgeoisie, especially the capitalist-roaders within, the Party; and it requires mobilizing the masses politically and increasing their mastery over all aspects of society, thereby digging away at the soil from which the bourgeoisie and its reactionary ideology constantly reemerges under socialism.

On just this question, Chou En-lai was taking a fundamentally revisionist line as early as 1956. When faced with the new tasks of advancing the socialist revolution, the bourgeois democrat of the earlier stage of the revolution can now be seen turning into a “Party person in power taking the capitalist road”–who is in a strategic position to institute revisionist policies throughout society, gradually usurp portions of power from the working class, and serve as the overall commander of the bourgeoisie’s social base for capitalist restoration, of whom the more privileged strata of intellectuals, government officials, and technical “experts” and so forth form a key part.

This is exactly the overall role that Chou En-lai ended up playing in the 1970s, when the class struggle centered on what stand to take towards the Cultural Revolution and the question of what road China would take was being raised more sharply than ever. However, this clearly went through a process of development. During the mass movements of the 1950s and ’60s, Mao was able to win Chou’s support at key points–though this was often given begrudgingly since Chou never fundamentally united with the revolutionary thrust of these struggles.

This was primarily because Chou and other bourgeois democrats like him did support some of the transformations which cleared away China’s economic and cultural backwardness, particularly if the victories could later–after the mass movements had subsided–be turned into capital to bolster their power and authority. In an important pamphlet released in 1975, On Exercising All-Round Dictatorship over the Bourgeoisie, Chang Chun-chiao touched directly on this subject. Referring to “some comrades among us who have joined the Communist Party organizationally but not ideologically,” Chang wrote:

They do approve of the dictatorship of the proletariat at a certain stage and within a certain sphere and are pleased with certain victories of the proletariat, because they will bring them some gains; once they have secured these gains, they feel it’s time to settle down and feather their cosy nests. (Page 18.)

Furthermore, when faced with the rising tide of mass struggle, especially at the beginning stages of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, Chou and others could sense which way the political winds were blowing and had enough sense to jump on for the ride in order to protect their positions. But by the early 1970s, Chou no longer saw this as necessary.

In fact a great opportunity presented itself to “get off the bus”–to make a decisive stand against the forward march of the revolution. The Lin Piao affair, the growing Soviet threat to China and the growing resistance among many Party leaders and cadre to the unprecedented breakthroughs and transformations of the Cultural Revolution all brought out Chou’s longstanding revisionist tendencies and crystallized them into a fully counter-revolutionary line–placing Chou and other veteran Party leaders allied with him directly in opposition to Mao and the proletarian headquarters he led.

In his famous speech at Lushan in 1959, Mao said that Chou En-lai had “wavered” in 1956-57 during the beginning stirrings of the mass upheavals that broke out with full force in the Great Leap Forward in 1958-59. In ideological terms, Mao labeled this “the sad and dismal flatness and pessimism of the bourgeoisie.” At the same time, Mao noted that Chou was an example of people who were conservative earlier but now “stand firm.” (Chairman Mao Talks to the People, Talks and Letters: 1956-1971, edited by Stuart Schram, p. 138.)

However, only several years later–in the situation of the sudden pull-out of Soviet aid and a string of natural calamities–Chou “wavered” once more, joining forces with the revisionists centered around Liu Shao-chi and Teng Hsiao-ping to reverse many of the revolutionary transformations made during the Great Leap Forward. Chou apparently had a hand in formulating the infamous “70 points” for industry in the early 1960s (which among other things reinstituted bonuses and piece-work, adopted rules and regulations putting profit and industrial “experts” in command, and cut back the time workers spent in political study and struggle).

Mao often pointed out that at the start of the Cultural Revolution the majority of the old guard on the Central Committee disagreed with him, calling his views “outdated.” In fact, Mao later said, “I was the only one to agree with my opinion at times.” While Mao struggled with and eventually won over Chou and many of the other crusty Party officials grouped around him to go along with the Cultural Revolution, he clearly felt it was necessary to pass over most of these people in forming a leading group to carry forward the revolution. Mao and the revolutionary Left–in which the four proletarian revolutionaries now vilified as the “gang of four” played a leading role–mobilized the masses to strike down the pro-Soviet revisionist headquarters centered around Liu Shao-chi and later the headquarters of Lin Piao and to assert their control and increase their mastery of every sphere of society. But, at the same time, the veteran Party leaders centered around Chou En-lai tried to narrow the scope of the Cultural Revolution and at times attempted to outright put a stop to it (as they did in early 1967). To a large extent, Chou’s role consisted of guarding against “excesses” and protecting and shielding many of these same conservative Party bureaucrats from mass criticism.

By this time Chou En-lai and other top Party leaders allied with him had concluded that China’s defense and economic construction depended on accommodation and alliance with the Western imperialist countries–a consistent feature of Chou’s thinking since perhaps as far back as 1949 or even further. Chou’s policies–that of placing modernization above class struggle, putting bourgeois experts and “efficiency” in command, telling the workers and peasants to stay in their place, and like it, and throwing the door open to the exploitation of China by foreign capital in exchange for advanced technology–had much in common with the revisionist lines that came under fire during the first few years of the Cultural Revolution (with the main difference being that Liu Shao-chi, “China’s Khrushchev,” and Lin Piao after him, were advocating capitulation to the Soviet social-imperialists instead of to the imperialist West). Chou En-lai and others saw that their interests would be best served by the defeat of these Soviet-style revisionists; thus they joined forces with Mao and the revolutionary Left, who saw that Liu and later Lin Piao posed the most immediate danger of usurping power and dragging China back to capitalism.

By the end of 1971, a bourgeois headquarters which increasingly had Chou as its prime sponsor was in an extremely powerful position, due to both the internal and international factors. Lin Piao’s treachery threw many of the achievements of the Cultural Revolution into question, the possibility of a Soviet attack on China had increased considerably, and there were many Party cadre and some sections of the masses who were tiring of the mass struggle.

In the name of opposing Lin Piao, the Right–led by Chou En-lai–argued for rehabilitating the overwhelming majority of cadre knocked down during the Cultural Revolution, including unrepentant capitalist roaders such as Teng Hsiao-ping, with little more than a token self-criticism. In the name of fending off a Soviet attack, the Right–again led by Chou–jumped on the necessity of making an “opening to the West” to advocate forming a strategic alliance with U.S. imperialism and its bloc and dropping support for revolutionary struggles around the world. (See “Three Worlds Strategy: Apology for Capitulation” in November 1978 Revolution for more on Chou En-lai’s role in developing and implementing this reactionary international line.)

At this point in time, Mao saw the need to rehabilitate many cadre, but only on the basis of the Party maintaining a firm proletarian line, and certainly not on the basis of reversing the correct verdicts of the Cultural Revolution. Mao apparently agreed to bring back Teng Hsiao-ping because of the need to consolidate things after the Lin Piao affair, but Mao insisted Teng make a self-criticism and pledge to support the Cultural Revolution–which could be and later was used against him when he jumped out again. Mao also saw the need to make certain agreements and compromises with the West to deal with the growing Soviet threat to China. However, Mao was agreeing to some of Chou’s policies with completely different objectives in mind, as was to become clear later.

According to the Right it was now time to restore order, cut out all these mass political movements, and get back down to what really counts–the task of building China into a great modern country. The Cultural Revolution not only had to be declared over, but the many revolutionary transformations that it brought about–including revolutionary committees in factories to replace one-man management, the settling of educated youth in the countryside, and open-door scientific research–had to be attacked and reversed. Though Teng Hsiao-ping served as the Right’s open hatchet man, the current rulers give Chou full credit for spearheading a move to restore the old educational policies criticized during the Cultural Revolution, particularly calling for “raising standards” and for the enrollment of part of the college students directly from “talented” senior middle school graduates.

Mao undoubtedly struggled with Chou to reverse his reactionary line right up until Chou died in January 1976–particularly because Mao recognized that Chou had a powerful social base among Party cadres, intellectuals and sections of the masses, and Mao recognized the necessity of winning over as much of those as possible. However, Mao harbored no illusions about Chou and what he was up to.

Immediately after the Tenth Party Congress in late 1973, Mao, allied closely with the Four, opened up fire directly on the rightist headquarters led by Chou and most aggressively championed by Teng Hsiao-ping. This life-and-death struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie intensified right up to October 1976, when the Right took advantage of Mao’s death and mustered their forces to pull off a counterrevolutionary coup d’etat.

In each of the campaigns initiated by Mao–from Criticize Lin Piao and Confucius in 1973, Study the Theory of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat and Combat and Prevent Revisionism, Criticize Water Margin, to Criticize Teng and Beat Back the Right Deviationist Wind in 1976–Mao and the Four were in various forms attacking Chou’s counter-revolutionary political line and all but explicitly attacked him in name. This was particularly true of the Lin Piao/Confucius and the Water Margin campaigns, which indirectly targeted Teng, and Chou behind him, as modern-day Confucianists and renegades who were intent on opposing the revolution, restoring capitalism and capitulating to imperialism. (See The Loss in China and the Revolutionary Legacy of Mao Tsetung, an important speech by Bob Avakian, Chairman of the Central Committee of the RCP, pp. 61-93, for a more thorough analysis of this period.)

In these final years, Chou was acting behind the scenes, using his considerable bureaucratic powers to place leading Rightists in important Party and government posts, and unleashing a social base for capitalist restoration under the signboard of “modernization.” Mao, just as typically, was initiating mass campaigns to criticize the capitalist roaders and get at the roots of revisionism; he threw his support squarely behind further socialist transformation, particularly the “socialist new things” brought about through the Cultural Revolution and he treid every possible means to politically arm and mobilize the masses to guard against revisionism, take the road of revolution and keep their sights set on the lofty goal of communism.

Thus, Mao Tsetung and Chou En-lai–and the proletarian and bourgeois headquarters they represented–ended up in fundamental and total opposition to each other. Even two decades earlier, as shown by an analysis of their differing speeches in 1949 and 1956, their world outlooks differed radically. As Mao pointed out in the last years of his life, with the advance and deepening of the socialist revolution, it was an objective law that “ghosts and demons”–especially top Party leaders such as Chou En-lai and his revisionist predecessors like Liu and Lin–would jump out every few years for a trial of strength with the proletariat.

It is only within the last year that our Party has correctly summed up the actual role played by Chou En-lai in the Chinese revolution. In January 1976, just after Chou’s death, Revolution carried an article calling Chou a revolutionary and a communist all his life. Though the Party followed the line struggle in China closely, and placed its support squarely behind the revolutionary line, we did not understand thoroughly the role that many individuals, including Chou En-lai, were playing at that time. This was also compounded by the influence of the revisionist Jarvis/Bergman headquarters in the RCP, who shared the revisionist line of the current rulers and who all along looked to Chou as their idea of a “model communist.”

Through the decisive defeat of these revisionists in our Party in late 1977, the RCP reached correct conclusions about the class nature of the current Chinese rulers, as well as about Chou’s role–which has been revealed all the more clearly by the Chinese revisionists themselves in the last year, with more certainly to come.

Therefore we obviously have to repudiate the position we took on Chou En-lai in 1976. Instead of being “a communist all his life,” Chou was in fact a bourgeois democrat all his life, who ended up commanding, and then in death became the rallying point for, the counter-revolutionary forces that have re-imposed the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie on the Chinese people and are now dragging China back to the living hell of capitalism.

The full glory of Chou En-lai’s line is now being displayed in China, enshrined in the “four modernizations” and the “three worlds” strategy of capitulating to imperialism. This is truly a fitting conclusion to Chou’s life, for he will go down in history as a bitter enemy of the proletariat and a leading representative of the Chinese bourgeoisie who tried to turn back the forward march of the international working class towards communism.