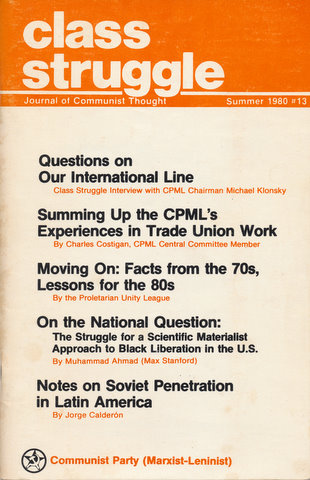

First Published: Class Struggle, No. 13, Summer 1980.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

Class Struggle Note: Charles Costigan is a member of the Central Committee of the CPML and is in charge of its trade union work. As part of the Party’s preparations for its second congress, its trade union activists have been engaged in an extensive examination, critique and sum-up of communist experiences in the labor movement over the last several years.

* * *

The CPML, as well as the October League (M-L) and other organizations which preceded it, has always placed great significance on factory, shop and trade union organizing. From the beginning we have strived to become a factory-based organization with the maj ority of our units based at the point of production.

These efforts span only some 10 years or so. Nevertheless, through such struggles as the Mead strike, the building of the UAW Brotherhood caucus, the right-to-strike and right-to-ratify struggles in the USW, numerous wildcats and contract strikes in the coalfields; right up to the recent fight for a democratic union in Local 2 of the Culinary Workers and an 1199 organizing drive at Georgetown Hospital–through all this work, we have gained some rich and varied experience.

Of course, we have made our share of mistakes in attempting to organize in the trade unions. But all our experience, both positive and negative, has helped bring our work much more into line with the actual conditions in the U.S. workers movement–thus enabling us to gain a much better understanding of our tasks and goals in the trade unions.

Recently the CPML has spent a great deal of time summarizing this experience and carrying out an extensive examination and evaluation of our trade union policies and general line. We are attempting to develop not only a better understanding of the issues and demands in the shops and unions, but also a more accurate and realistic assessment of the consciousness of the workers and the various forces who control the trade unions. In this way we aim to correct wrong views which were evident in both our tactical and our strategic concepts of communist work in the trade unions.

I would like to use this opportunity to state my opinions on some of the main tenets, correct and incorrect, comprising our line and policies on the trade union question. Though not comprehensive, I hope this will contribute to the debate and to further unity among Marxist-Leninists and trade union activists on this very important question.

From the beginning we have seen the trade unions as the most basic, comprehensive organizations of the workers. We build them, defend them from capitalist attack and fight to transform them into organizations of class struggle. In the course of organizing in the shops and unions, we strive to win the broad masses of workers to see the need for socialist revolution and communist leadership.

Further, we recognize that the U.S. trade union movement is presently dominated by bureaucrats who have a basic interest in defending and preserving the capitalist system, rather than mobilizing the working class to fight it consistently or overthrow it. As part of the effort of the working class to successfully defend its interests and achieve its revolutionary goal of socialism, class collaborators in power in the unions must be replaced with genuine class fighters. The trade unions must be transformed into organizations that not only defend the daily interest of the workers, but also must be used as weapons in the hands of the workers to help overthrow the very system that exploits them.

We also view the trade unions as a vital component in establishing the alliance and merger of the workers movement and the liberation movements of the oppressed nationalities and for building working class unity. As such they must work in support of the fight against discrimination, support the struggles of the peoples of the world fighting for independence and liberation, oppose superpower war preparations and play an active role in building the united front against hegemonism.

I believe these aspects of our line on trade union work to be correct and applicable to the direction the labor movement needs to take if it is to successfully mobilize the millions of organized and unorganized workers in a common fight against oppression and exploitation.

Yet there has also been an ultra-“left” deviation from Marxism in our line and policies, which has hindered our Party’s ability to organize. It has resulted in isolation and sectarianism in situations where we could have made gains. While its source dates back farther, this ultra-“left” deviation was formalized during a labor campaign which the OL initiated just prior to the founding of the CPML in 1977. This campaign took as its guiding principle the general line which was set forth in our Party Program’s trade union section. It was further elaborated in a pamphlet, “Building Class Struggle Unions,” which originally appeared as a series in The Call in the spring and summer of 1976.

Both the pamphlet and the section on trade unions in the Program contain wrong analysis and a number of incorrect formulations which led to an ultra-“left” practice. The campaign was summarized in the fall of 1978 in a Class Struggle article which, while criticizing some aspects of ultra-“leftism,” still did not recognize the basic problem.

There were some positive aspects to the Labor Campaign in that we stressed the decisiveness of the Party being factory-based. We emphasized the need for communists to carry out consistent revolutionary education among the workers, maintain our independence and initiative, and recruit class-conscious workers to the Party. We reaffirmed our revolutionary stand on the national question and its immediate as well as strategic importance to the labor movement. We also clearly stated our task as one of building class struggle unions and gained a better understanding of the common class character of the top labor bureaucrats controlling the unions.

But doctrinaire thinking infected both the initiating and carrying out of the labor campaign and resulted in our ignoring certain fundamental truths:

First, that the starting point of our work must be to proceed from actual conditions, not general or abstract formulations. During the labor campaign we overestimated both the consciousness and level of activity of the workers. Relying on formulas, we failed to make a scientific analysis of the forces and trends within the trade union movement and, on that basis, to understand more concretely the road to class struggle unionism.

Second, the recognition that our aims and policies change through different periods and stages of the struggle. We lacked such flexibility in the campaign.

And third, that the trade union bureaucrats are not one monolithic section of the labor movement. Both minor and major differences exist among the bureaucrats and between the bureaucrats and the bourgeoisie. We belittled these differences rather than taking advantage of them. For a time there was a tendency to view all union officials–from the international to the locals–as enemies. This not only cut us off from some militant and progressive union officials, but also led to our abstention from running for office ourselves.

In large part, on the basis of this incorrect analysis, an ultra-“left” approach was developed which was manifested in both our line and policies, and guided our work for a period of time. The main features of this ultra-“leftist” deviation and its application were:

1) That we aim the main blow against the reformist and revisionist bureaucrats and further that we especially target the most liberal or “left” social-democratic union leaders. This theory of the main blow was a dogmatic application of some of Stalin’s writings to the U.S. labor movement. It’s not applicable today and has been a premise for cutting us off from alliances which would have furthered the class struggle.

Communists and union activists, of course, should have the objective of replacing class collaborators in power with class fighters. By class fighters I refer to those workers, holding union office and not, whose thinking and actions represent the interests of the broad masses and have their support in the fight against exploitation. But to aim the main blow at the entire stratum of trade union leaders negates the task of communists to make use of contradictions in both an immediate and long-range sense and to support and build the progressive trend which is growing within the labor movement. This progressive trend is not “pure.” The vast majority of workers in it are reformist-minded rather than revolutionary-minded. And whether we like it or not, it also includes a number of new-style opportunist leaders who have their own contradictions with the brand of opportunism of the dominant and die-hard sections of the labor bureaucracy.

The only usefulness for the concept of aiming the main blow is in isolating and targetting those die-hard class collaborators who are the principal roadblock to advancing the struggle and organization of the workers in any given situation.

The most vivid example of the practical results of incorrectly aiming the main blow (with a particular emphasis on attacking the most social-democratic union officials) was our boycott of the Sadlowski election in the steelworkers union.

Our overall analysis of Sadlowski as an opportunist bureaucrat and our criticisms of his lack of a program and organization were correct. But our basic premise for the boycott was that he was not a “real alternative” to McBride; that he was becoming exposed in the eyes of a significant section of workers and that through the boycott we could win these workers–particularly the advanced–to our cause and party.

In fact, Sadlowski was not exposed to any significant amount of workers (especially outside District 31), and actually many class-conscious workers actively supported him. As for Sadlowski being a “real alternative”: the differences between Sadlowski and McBride are not over their class outlook, but at the time of the election, Sadlowski, his program and the reform movement around him did represent an alternative of which we should have united with.

But boycotting his election served to temporarily isolate us from the reform movement in the USW. Sadlowski was the recognized leader of that movement. By working in the campaign, by fighting for organization and programmatic opposition to McBride and the steel monopolies, and by carrying out our right to criticize and to do independent education, we would have contributed both to expanding our influence, and furthering the reform movement in the USW.

2) That we only make alliances with reformist or revisionist bureaucrats from a position of strength, or as we said in the pamphlet, “when we had the ability to sever the workers from the influence of the bureaucrats.” Further, that we make these alliances only in order to expose the opportunist union leaders.

This isolationist policy negates the necessity of having a united front approach to organizing in the labor movement. The implementation of this policy placed us in opposition to progressive caucuses and coalitions which were forming.

At present, communists are certainly not strong enough to sever the workers from the opportunists’ influence. This is a protracted process. We should utilize alliances with the trade union bureaucrats. In doing so we gain access to larger numbers of workers and our experience has shown that through these alliances we can also strengthen the fighting ability and organization of the workers, win some victories and win the respect of workers as well. In many situations these alliances actually provide better conditions for exposing opportunists when they turn against the rank and file.

3) That it is wrong to “pressure” the bureaucrats to take actions that are in the interest of the workers. We had the view that to do so would foment illusions about the true class nature of the bureaucrats. This is idealistic. The bureaucrats run the unions and we should demand that they implement policies that are in the interest of the workers and mobilize the rank and file to fight around those policies. Our policy should be: unity around those issues which advance the workers struggle, develop their organization and struggle against class collaboration.

In the same vein, our program contained a one-sided critique of trade unionism, which in practice led to opposing militant fighters who were for building a strong trade union movement but did not agree with the communists’ program on every issue. Trade unionism is a reformist rather than revolutionary ideology, but it can also concretely oppose capitalist policy and attacks. In the course of our work we should show the limitations and basic inability of trade unionism in attaining working-class political power and emancipation. In particular we should oppose the Meany-Fitzpatrick brand of trade unionism which attempts to convince workers that through cooperation with the capitalists they can attain a bigger piece of the pie. But in a country where 80% of the workforce is unorganized and the existing unions relatively weak, militant trade unionism plays a progressive role in combatting an anti-union perspective and building and strengthening the labor movement.

And finally on this point, our analysis and critique of the labor aristocracy was also one-sided and too sweeping. There is a privileged strata within the working class that has benefited from U.S. imperialism’s superprofits. But its size, strength and the stand of different forces within it can shift with changing conditions. It was wrong for us to place all full-time labor officials in the ranks of the labor aristocracy and further incorrect to state that they as well as “labor aristocrats are all enemies of the working class....”

This resulted in a sectarian policy toward some highly skilled white workers who did have privileges, racist ideas and supported the role of the U.S. government abroad; but who, nevertheless, have contradictions with the bosses and some sell-out union leaders. At present, we are doing some organizing among some highly skilled workers in industries like auto and steel who are fighting cutbacks, job eliminations and inaction on the part of union officials.

4) Another example of ultra-“leftism” which affected our work was a one-sided emphasis on revolutionary education over day-to-day organizing. We quickly recognized and criticized this tendency; however, after correctly adopting a policy of “combining education with action,” problems still persisted. We had a tendency to focus on communism in an abstract fashion as the objective in our popular education. Much of our shop agitation suffered from stereotyped writing and phrase mongering. Too often, our literature addressing national oppression raised demands which were not backed up by practice aimed at organizing a multinational fight against discrimination.

Not enough attention was paid to producing literature on some of the immediate issues facing the workers. Our final aims often were separated from our day-to-day organizing. This was particularly true of independent party leaflets. These need not be confined to the fight to overthrow capitalism; rather the party should popularize its views on important struggles the workers are engaged in. We should try to be more selective and proficient in leaflet work, and at influencing the content and direction of agitational materials which have a broader audience–and even materials controlled by the opportunists. For instance, over the past two years, we have consciously participated in a good number of official union newsletters and shop papers, apart from our own. A number of our comrades are now editors of these papers.

It is our view that The Call can eventually become accessible to the broad masses of workers. At times in the past, while our comrades worked hard to sell as many Calls in the shops as possible, distribution was sometimes seen in conflict with organizing around trade union and shop issues. We sold a lot of papers but our readership was not really that stable. Our factory units should approach distribution of the paper in more of a planned way– utilizing good opportunities to do mass distribution while persistently building up a stable readership, largely through subscriptions. We should also aim to organize the workers inside the shops to become actively involved in distribution, discussing and writing for The Call.

Unquestionably, these errors hindered our Party’s trade union organizing during the first two years following our Party Congress. Despite these errors, we still carried out some successful organizing in the shops and unions and recruited workers to the CPML. The materials we published, while containing errors, also elaborate on correct views and contain many good points.

Through our experience we’ve come to recognize that ultra-“leftist” errors can damage our Party’s ability to organize just as much as rightist errors. Leftism can shackle excellent factory organizers, promote sectarian attitudes towards important reform movements, promote disdain towards the economic struggle and work within the trade union structure as well as the fight for progressive legislation. Ultra-“leftism,” like rightism, is a blockade to building class struggle unions and winning the workers to communism.

This is not to say that we do not recognize the danger of rightism in our work, in both an immediate and long-range sense. We have adopted the approach of fighting on two fronts while emphasizing the fight against doctrinaire thinking. I believe a thorough-going critique and break with ultra-“leftism” is essential if we are to effectively fight liquidationism, tailism and economism.

Within the CPML, the struggle to overcome ultra-“left” deviations and rectify our work has provided a great impetus to expanding our labor work on a good footing. Our West Coast organizing provides two good examples of this. A year and a half ago in both Local 2 of the Culinary Workers and Local 923 of the UAW we pursued an isolationist and sectarian approach to the trade union struggle, aiming the main blow at reformist leaders and boycotting important elections and we were left standing on the sidelines. In criticizing this approach, we moved towards a policy which could better unite the progressive forces, win over the workers to a common program and narrow the target of our attack. This change in policy resulted in our comrades becoming much more active in organizing, gaining access to and winning the respect of many more workers, thus aiding the advancement of the struggle and winning some positions in the union.

In making an overall estimation, I believe the workers’ movement to presently be in a relatively defensive position. The lack of rank-and-file control of the unions, the low level of unionization and revolutionary influence, the stepped-up attacks by the capitalists and increased chauvinist propaganda all threaten the livelihood and unity of the working class.

But there is also a growing discontent among the workers and outbreaks of struggle are not uncommon. Further, the schism between different forces in the trade union bureaucracy and between a section of the trade union leadership and the bourgeoisie is widening.

While our analysis of the forces presently controlling the trade unions is not complete, we are paying particular attention to the growing “left” social-democratic trend within the labor movement. How should we assess this trend and its call for fighting “corporate power,” for organizing the unorganized and opposition to discrimination? On the one hand, we consider this a positive development which should be pushed forward. We organize in, to the best of our abilities, activities such as Big Business day, opposition to the Schweiker Bill, and conferences like the one in Ann Arbor addressing the direction of the labor movement in the ’80s. We are also increasing our work in support of specific legislation, such as the Conyers Bill for a shorter work week and the Ford-Riegle Bill against plant shutdowns.

On the other hand, we recognize that the leadership of this trend is not revolutionary and in fact is opposed to Marxism-Leninism, and we must be vigilant against its influence in our ranks. Further, gains in any of these areas will only come about through mobilizing the rank and file to fight. While speaking of this trend in a general sense we know that differences exist among the trade union leaders who represent it–on international as well as domestic questions.

Transforming the trade unions necessitates that communists and progressive trade unions take up the immediate economic issues facing workers today in order to link them up with politics. And while the trade unions are organizations which mainly defend and advance the workers economic interest, it is my belief that a large number of workers will respond to political issues if leadership and organization is provided.

The CPML believes that in our trade union work we have a special duty to build internationalism, oppose war preparations and defend world peace. We have tried to do this through campaigns such as support for the liberation struggles in southern Africa as well as in our criticisms of the anti-import campaign of the U AW leaders. Recently we have been successful in fighting for and having union resolutions passed in opposition to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and against the deportation of Iranians in the U.S.

Because of these differences and the fact that this trend and the overall momentum among the rank and file is at an embryonic stage, I believe it’s wrong to call for a “left-center coalition” strategy for the trade union movement. Among Marxist-Leninists who do so, there is a danger of trying to apply historical formulations to present conditions which are very different in many ways. Our movement lacks an accurate historical summary of communist work in the U.S. labor movement as well as an understanding of who constitutes the left and center in a strategic sense. As for the revisionist CPUSA and their left-“floating” center strategy, they use it principally to define the pro-appeasement or pro-Soviet section of the labor bureaucracy which they try to promote.

But I do believe that there is a need for communists to have a more long-range view of how to make use of these existing contradictions among the union leadership and between the union leadership and the ruling class. Should our alliances have only an immediate and temporary character, or is there the possibility of splitting off a section of the trade union leadership, pushing them more in the direction of class struggle and in opposition to the capitalists and their parties?

I believe this is not only possible but an absolutely necessary part of a communist strategy for transforming the trade unions. Without such a split it will be impossible to organize a progressive labor movement. It is in this context that we should examine the viability of building up a labor party which could provide a mass alternative for the progressive trend within the trade union movement and those disenchanted with the capitalist parties.

The CPML takes multinational unity as the cornerstone of our trade union work and as such has tried to consistently fight for the special demands of the oppressed nationalities in the shops and unions. This has included the fight for affirmative action, bilingual translations and opposition to deportations.

We believe that the vast majority of white workers can be won to support not only the immediate demands against discrimination but the general fight against national oppression because it is in their class interest to do so. On this basis we can take fights such as the defense of Smitty and Bennie Lenard in the UAW, Terrence Johnson at Georgetown and the fight against the Ku Klux Klan in Greensboro right into the workplace and unions in order to more effectively organize and educate the workers. This work is protracted and we must be careful not to take these campaigns up in an abstract way or create an artificial separation between the fight against national oppression and for internationalism and economic and trade union issues.

Over the past year we have taken steps to expand our work with white workers. Within our Party we attempt to carry out a division of labor, with our white comrades doing the bulk of our organizing among white workers.

We are also beginning to put out special agitation directed to white workers with the aim of building multinational unity and combatting chauvinism. In developing these materials we try and take into account differences in culture and experience. One recent example was in a contract struggle at a hospital in Boston. White workers from South Boston made up 40% of the workforce. We put out special literature exposing the ties that a racist city councilman from South Boston had with the Klan. This same councilman was calling for cutbacks in the city budget which would result in layoffs and wage cuts at the hospital and a weak contract. We showed the relationship between the two and on that basis united white and minority workers in a common fight for a good contract and against the racist politician.

We have also tried to improve our work in fighting for the special demands of women on the job who now make up some 44% of the workforce. In a number of unions we have initiated or are working in women’s committees. Wherever possible we have fought for official union recognition of these committees. Men and women workers of all nationalities are feeling the effects of the economic decline, growing layoffs and plant closures. Minority and women workers face a special discriminatory effect. Under these conditions, some of the demands we are fighting for include: voluntary inverse seniority during layoffs, indefinite recall rights for all workers, extended unemployment, SUB and health benefits during layoffs, retirement at 25 years with full pension, (20 years or less in the case of plant shutdowns) and special affirmative credits to women and minorities for retirement, where they had been denied employment earlier in the industry. As stated earlier we are also organizing in support of specific legislation. A legislative struggle where we’ve had the most success is the fight for implementation of the Pregnancy Disability Act in industry.

Taking up these broader issues assists us in combatting the narrow business unionism promoted by a section of the bureaucracy. Further, it provides a good arena for carrying out our independent work and doing mass revolutionary education among the workers. Of course our independent work is not confined to political questions, but many times it’s on these issues that workers can distinguish the communists’ program from the program of the social democrats and revisionists.

In conclusion I’d like to say that not only should we have an all-sided approach to our organizing (economic and political) but a multi-level approach as well. That is, we organize on the shop floor; we organize the unorganized into unions; we organize within the trade union structure, including holding positions as well as building caucuses where there is a basis for them; and we organize in the labor movement overall including support, staff, coalition and legislative work.