At first glance, anti-revisionism has a mixed pedigree in Ireland. Whereas the Cork Workers Group upheld the Irish national liberation struggle as the principle one for Communists to engage in, the British and Irish Communist Organisation (BICO) was to pursue a line of capitulation to British rule in Ireland. Yet it was these activists, émigrés in London, and English students studying in Dublin, that contributed to the first expressions of organisational anti-revisionism on the Irish isle.

Starting from scratch, the anti-revisionist elements were faced with the unresolved national question, a pre-existing republican movement committed to armed struggle in the North, a two-party political system dominated by the bitter legacies of Republican historical rivalries, and a Labour movement, radical in history but revisionist in leadership. Against the background of Ireland’s theocratic culture and conformity, all these factors narrowed the political space for other radical organisations to develop to the left of the existing Republican and Communist movements in Ireland. Nineteen Sixties’ Ireland had less the features of a developed industrial society and more a neo-colonial relationship with Britain which remained in occupation of the arbitrarily-drawn six counties of Ulster.

Notable antecedents of Irish anti-revisionism included Irish communists like Hamilton Neil Goold-Verschoyle, an Irish Communist who moved to England in the early 1950s, and was active in the Connolly Association in London. In 1956 Goold published a pamphlet, The Twentieth Congress and After: A Vindication of J. V. Stalin and His Policy. A sprinkling of other Irish anti-revisionists, like Noel Jenkins, populated the London émigré scene, yet there was no substantial organisational expression within Ireland itself. For a moment in the mid-Sixties it was some how identified with the Irish Communist Group, an amalgamation of Stalinists, Maoists, Republicans and Trostkyists based in England as much as Ireland. The organisational evolution of the “Maoist” element into the British and Irish Communist Organisation – the title itself an indication of its lack of Maoist presence (where is that familiar ML suffix?) – is indicative of the difficulties in placing it within that political tendency.

The self-declared Maoism of the Trinity College student radicals, the Internationalists, who formed the basis of what was to emerge as the Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist) in the early 1970s is much clearer, even if it only lasted seven years at most, before Maoism was abandoned in favour of allegiance to Enver Hoxha and the Party of Labor of Albania.

In the 1980s Dublin saw the fleeting existence of another anti-revisionist formation, An Spreach, [The Spark]. The new century saw references to the Irish Maoists of the World People’s Resistance Movement.

And throughout it all there was the red thread of another, once inspired by the Maoist arguments of the early 1960s, the Irish revolutionary republican from Cork, Jim Lane. Active in the Irish Republican Army, establishing anti-imperialist solidarity movement, resurrecting the rich radical political heritage in Irish history through publishing activity via the Cork Workers’ Club, defending the Hunger Strikers in the north and becoming national chairperson of the Irish Socialist Republican Party in the 1980s, his politics reflected the Maoist way of doing things in that island.

For a wider exploration of the Irish left, and a rich source of various organisations’ publication visits the Irish Left Archive. The added bonus is that many documents are accompanied by a commentary from The Cedar Lounge Revolution website and its knowledgeable visitors. These introductory notes draw unashamedly upon them in acknowledgment of their valuable contribution to the public record.

Mao and The IRA’s Chinese Takeaway

Brendan Clifford left the Communist Party of Great Britain in October 1963, and while working in London, joined the anti-revisionists of the Committee to Defeat Revisionism, for Communist Unity (CDRCU). It was a brief commitment. As veteran Trotskyist Sean Matgamna tells it,

In 1963, Liam Daltun initiated a series of on-going discussions involving a wide spread of Irish leftists in London – Trotskyists like himself, “anti-revisionist” Communists, and left Republicans.” About the same time, at the behest of the CDRCU, Clifford and his wife Angela began to organize an Irish sub-section intended to compete with the Communist Party-influenced Connolly Association and perhaps lay the basis for a Marxist-Leninist group in Ireland.

The two small streams converged, or were already overlapped, and by May 1964 formed an organisation called the Irish Workers’ Group, which very soon changed its name to the Irish Communist Group (ICG). It was an independent organisation, not the front which the CDRCU had projected. From October 1964, the ICG would produce a small duplicated weekly news-sheet, Irish Workers’ News, and from February 1965 a monthly magazine, An Solas.

Few observers would challenge Matgamna’s view that,

The ICG evolved as a strange conglomeration of Stalinists, incipient Stalinists, Maoists, Republicans, and “Trotskyists”. One of its “Trotskyist” participants, Gery Lawless, would later justify himself to me on the grounds that the ICG was committed to “the workers’ republic” – socialism – as the “next stage” in Ireland, as against the typical Maoist-Stalinist assertion that the “next stage” had to be the “completion” of the “bourgeois-democratic” revolution there. That, I think, though it did not justify what Lawless did in the ICG, was true. The Maoists would retreat from it.

It seems that all the participants agreed to leave contentious political, historical and theoretical questions between them to be resolved later: meanwhile they would study Ireland and respond to public events as they arose…. They would suspend not disbelief but their beliefs.

Of course, they couldn’t and they didn’t.

In September 1965, the ICG split into Trotskyite and anti-Trotskyist factions. Clifford and “half a dozen” others endorsed the anti-Trotskyist position and formed the Irish Communist Organization (ICO) in November 1965.

What remained of the ICG was, according to Matgamna “a politically inchoate conglomerate, kept together by the fact of being émigré Irish. The “Trotskyist” ICG soon changed its name to the Irish Workers’ Group.”

The ICO’s London section formed a part of the city’s anti-revisionist current, publishing the first issue of “The Communist” in March 1967, and engaging in the political cut and thrust debates. ICO engaged in discussions and activities with other groups, including initiating a meeting with the leadership of the Communist Federation of Britain (ML) in November 1970. In the heated atmosphere of the anti-revisionist struggle, however, shifting alliances and splits occurred.

Bad relations soon arose between ICO and another emerging Irish anti-revisionist formations, the Internationalists organized around Hardial Bains. This was clearly demonstrated when the ICO walked out of the “Necessity for Change” conference organised by the Internationalists. That set the tone for their political relationship. In 1975, the Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist), successor to the Internationalists, produced the pamphlet “Differentiate between sham & genuine Marxism-Leninism”, a scathing attack on the BICO and Brendan Clifford.

ICO maintained the regular publication of “The Communist” magazine from 1967-1986. The journal rarely shied away from controversy with headlines written to attract attention, such as “Is Mao A Fascist?”. Clifford provoke a 15,000+ worded reply from Ted Grant (extract published in his The Unbroken Thread), entitled “A Reply to Comrade Clifford” on the question of the difference between Stalinism and Trotskyism. Clifford would repeatedly return in print to the question of Stalin as with “The Communist” July 1979 “Special Stalin Centenary Issue”.

While the ICO generally took a pro-Chinese and Albanian position in international politics, its views were largely motivated by a defence of Stalin and the Soviet experience. In fact, the ICO undertook an investigation into the development of Maoism, and concluded that it was not a suitable model for an anti-revisionist group because, it claimed, Mao had supported the development of Khrushchev’s ”revisionism”. Anti-revisionist maybe, but the ICO was far from a “Maoist” group. This was clearer when the organisation began to produce an analysis on the issue of partition and its work on the “historic Irish nation” that contradicted any notion of a national liberation struggle existing in modern Ireland. Instead it was argued that there were two distinct people in the isle of Ireland who constituted “two nations” each entitled to the expression of its structural existence.

The change of organisational name from ICO to British and Irish Communist Organisation in 1971 was said to reflect an operational reality with members on both islands. However it also marked a distinct political reorientation that had occurred in the thinking of the ICO leadership after the promotion of its “two nations theory,” a reorientation which led in an increasingly less Marxist direction.

In addition to its original take on the Irish national question, BICO, through its member, Bill Warren, proposed an alternative approach to issues of imperialism. His work argued against the grain that:

the period since the Second World War has been marked by a major upsurge in capitalist social relations and productive forces (especially industrialization) in the Third World; that in so far as there are obstacles to this development, they originate not in current imperialist-Third World relationships, but almost entirely from the internal contradictions of the Third World itself; that the imperialist countries’ policies and their overall impact on the Third World actually favour its industrialization; and that the ties of dependence binding the Third World to the imperialist countries have been, and are being, markedly loosened, with the consequence that the distribution of power within the capitalist world is becoming less uneven. [“Imperialism and Capitalist Industrialization” New Left Review [Sept-Oct 1973]]

This was an analysis that generated many polemical responses and reinforced the questioning of the group’s Marxist credentials which had evaporated as the years progressed.

BICO’s evolving positions, particularly on the Irish national question, were met by dissension from within. Members in southern Ireland who opposed the new direction on the Irish struggle (including Jim Lane) resigned to form the Cork Workers’ Club.

In 1974 more dissidents with the BICO’s policy initiatives, which at the time included support for the Ulster Workers Council Strike, left and formed the Communist Organisation in the British Isles (COBI).

The BICO was never officially disbanded. In the 1990s its members remained prolific publishers, with the Irish Political Review as the direct lineal descendent of British and Irish Communist Organisation publications including Workers’ Weekly and Northern Star. Also in the stable of online and print publications are Labour & Trade Union Review, Church & State, and Problems of Capitalism & Socialism. Clifford and his diminished band of co-thinkers came to work solely through the Ernest Bevin Society, maintaining the publishing outlet of Athol Books, and increasing, having produced over 30 publications, worked through the Aubane Historical Society, which essentially concentrates on the local Aubane and Millstreet area as well as North Cork generally but, through linked sites, still comments on a wider stage.

EROL thanks the Irish Left Archive for its work in making many of the following documents available on their website.

We also want to acknowledge that some of the texts here have been reproduced from the Athol Books website.

Notes on the Evolution of the B&ICO by Sam Richards

British and Irish ’Communist’ Organization – Trotskyite thugs, sham Marxist-Leninists and agents of British imperialism by the Marxist-Leninist Institute, Ireland

Irish Communist Organisation and China by the Communist Unity Organization

Nina Fishman obituary by Donald Sassoon

Nina Fishman, 1946–2009 by Manus O’Riordan

The Economics of Partition by the Irish Communist Organization

On the “Usefulness” of “Economics of Partition” by G.M., Communist Federation of Britain (Marxist-Leninist)

Obituary on Micheal McCreery by the Irish Communist Group

The Economics of Revisionism by the Irish Communist Organization

In Defense of Leninism by the Irish Communist Organization

The Communist Party of China and the 20th Congress of the C.P.S.U

Capital and Revisionism [Irish Communist Organization pamphlet #9]

The British Road to Socialism by Nina Stead [Nina Fishman]

The British Road to Socialism – A Reply to Criticisms by Nina Stead [Nina Fishman]

The Irish Communist, Issue #94

The Ulster General Strike (1974) [including Strike Bulletins of the Workers’ Association]

The Politics of Revolutionary China

The Question of the Stalin Question

Whither Northern Ireland? by Brendan Clifford

Communist Comment, No. 17, August 15, 1970

Comment, Vol. 2, No. 3, June 22, 1973

Comment, Vol. 3, No. 4, March 29, 1974

Problems of Capitalism & Socialism

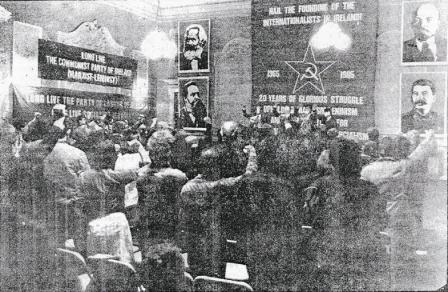

The Internationalists, later the Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist) (CPI-ML), emerged at Trinity College, Dublin in November 1965 from a group centred around an Indian academic named Hardial Bains. Through the Internationalists, Bains also set up parties in England, Canada and elsewhere, all of which were noted for their frenzied ultra-leftism.

When the Internationalists were first organized, they were not a fully-formed Marxist-Leninist organization, but a radical student group. In August 1967 they held a conference in London with other elements of the anti-revisionist left focused on the ideas expressed in Hardial Bains’ pamphlet the Necessity for Change! The Dialectic Lives!. The Conference lasted two weeks, and among the groups invited were the Irish Communist Organisation. Talks of a merger between the two groups came to nothing, and in fact a serious animosity developed, seen in the following years, in the pages of their respective publications.

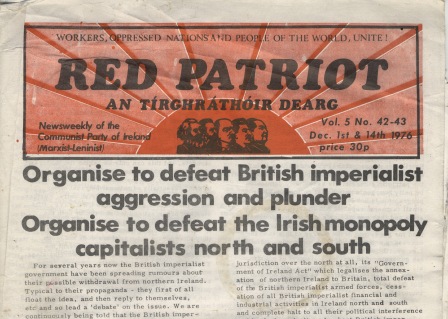

Towards the end of 1967, after the London conference, the Trinity Internationalists became more radical and politically active. In August 1969 under the name, Irish Revolutionary Youth, they began issuing a monthly newspaper entitled Red Patriot. The following year, in July 1970, the Internationalists relaunched themselves as the Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist).

Like its sister parties in England and Canada, the CPI (ML) gave rise to a variety of organisations associated with the Party: the Communist Youth Union of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist), the youth section of the CPI (ML); the Workers and Unemployment Movement; and the Party-initiated Spirit of Freedom Committee to work with Irish republicans.

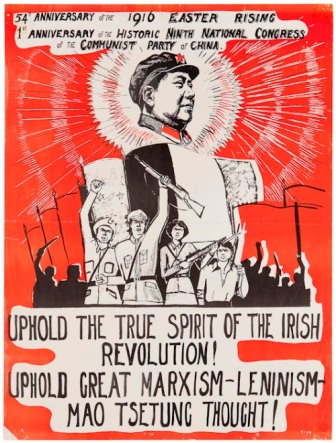

The CPI (ML) initially distinguished itself by its fervent Maoism. The following quote is typical of their materials in the early years (as is the extensive use of capital letters):

The experience of the Bolshevik Party, and of the Communist Party of China, particularly of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and also the experience of our own movement shows that there are three fundamental building blocks for building the party. 1st and most important, UNQUESTIONING FAITH IN THE REVOLUTIONARY WILL AND CAPACITY OF THE PEOPLE. 2nd COMPLETE FAITH IN MARXISM LENINISM MAO TSETUNG THOUGHT. 3rd AND ABSOLUTE LOYALTY TO THE PARTY OR PARTY ORGANISATION!

However, the rupturing of the ’anti-revisionist movement’ occasioned by the Sino-Albanian political divorce in 1977, saw the CPI (ML) denounce China and then Mao Zedong Thought in an echo of sister parties in the ’Internationalists’ stable of organisations. CPI (ML) representatives duly attended international rallies to confirm the repudiation and condemnation of what they had been promoting for the previous decade. The CPI (ML) organised several delegations to Albania, the first in June 1979, meeting Albania leader, Ramiz Alia, and these visits continued in the 1980s.

The Special Consultative Conference of the CPI (ML) in September 1979 restated the denunciation by the Party of ’Mao Zedong Thought’, and its adoption alongside Marxism-Leninism when the organisation was founded on 4 July 1970. This was characterized as ’understandable mistake,’ but the Party never provided an analysis or explanation of why such a ’serious mistake’ was ’understandable’.

However, having overcame the adverse effects of ’Maoist revisionism’, the CPI(ML) faced a concerted attempts by ’revisionist cliques amongst the former leaders of the CPI(ML) to subvert and liquidate the party’ in the early 80s. Prominent CPI (ML) leaders – Carole Evans (nee Reakes), Alan Evans and David Vipond – were charged with acting as a faction in a long drawn out struggle over two years. Once the internal struggle finally ended, the CPI (ML) was re-launched at a Special Consultative Conference on the occasion of the Party’s Twelfth anniversary on July 4th, 1982.

1982 also saw the reappearance of the Red Patriot after a hiatus of more than two years as the Organ of the Central Committee. It was replaced in 1984 by The Voice of Revolution. By the end of the decade there was another name change when The Voice of Revolution was replaced by the four-page Marxist-Leninist Weekly. A single issue of a theoretical journal, The Marxist-Leninist Journal appeared in 1988. A bookshop was opened in Essex Street, but things were not as they had been earlier.

With the collapse of Albanian socialism, the CPI (ML) established relations with the Workers’ Party of Korea and signed the 1992 Pyongyang Declaration. General Secretary Rod Eley visited the DPRK in 1999. The Party was now only a shadow of its former self: smaller, less active, and more marginalised. It was not immune to the malaise and shrinkage that had affected the political Left generally throughout Europe.

The Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist) was formally dissolved on Sunday, 16 March 2003, bringing an end to the Internationalists trend in Ireland.

EROL thanks the Irish Left Archive for its work in making many of the following documents available on their website.

Short History of the Irish Internationalists/Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist), Part One: 1965-1970 by Conor McCabe

On the 20th anniversary of the Internationalists: The Myth of the Glorious Past–CPC(M-L)’s Pretext for International Factionalism by the Marxist-Leninist Party of the U.S.A.

Communism in the Schools by Michael Heney

The 1970 Springboks Tour and Local Politics in Limerick

Words by the Internationalists

Necessity for Change! by Hardial Bains

Mass Line in Education: Revolutionary v. Reactionary Line by the Internationalists

Communists Resist Harassment by British Imperialist Mercenary Troops in the North of Ireland

An Analysis of the Significance of the Ulster Workers’ Strike, May 14-30, 1974 [A series of articles from the Red Patriot]

Statement of the National Executive of the Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist) [Kevin Gately]

Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist) Hails the Internationalists

Basis of Struggle: For a Nationally Independent and Unified People’s Republic of Ireland 1976

The Theory of "Three Worlds" Is Not Consistent with Marxism-Leninism but with Opportunism

Unity and Freedom to the Irish People! Against Fascist 'Divide and Rule' Anglo-Irish Agreement 1986

Voice of the Youth: Uphold Democratic Principle! No to Apartheid-Style Anglo-Irish Agreement!, Communist Youth Union of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist) 1988

Announcement: Dissolution of the Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist)

The Irish Student, No. 1, May 24, 1967

Red Patriot/Voice of Revolution/Marxist-Leninist Weekly

The Cork Workers Club emerged from the Cork Communist Organisation. The latter had itself been formed in 1972 in reaction to the Irish Communist Organisation’s shift from a Republican standpoint to a ’two nations’ and functionally pro-Unionist one.

Running through these different organisations, and others, is the presence of an individual who encapsulates the various threads within the radical left scene in Ireland. That individual, Cork-based Jim Lane, joined the (IRA, Sinn Fein and the Cork Volunteers’ Pipe Band in 1954. He subsequently participated in Operation Harvest in 1956 (an operation involving up to 150 Volunteers during which the IRA attacked targets in all of the Six Counties).

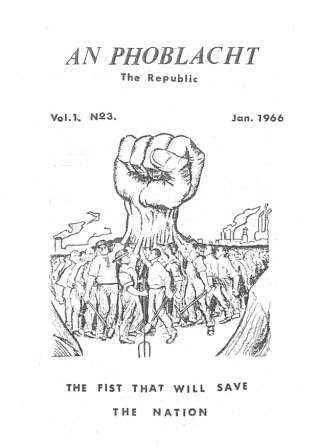

Jim Lane was also involved with the Unemployed Protest Movement in the late 1950s and was instrumental in establishing the Cork Vietnamese Freedom Association in the 1960s. He was a leading figure throughout the 1960s in a group called the Irish Revolutionary Forces, the Cork-based group that produced an influential publication called An Phoblacht.

This paper openly criticised the Republican Movement for its lack of action on the north and for reneging on republican principles. There was considerable tension between the IRF and the IRA, which turned into raids and armed counter-raids. In 1963, for example, a group of eight armed IRF members raided the Cork Sinn Féin headquarters and threatened the city’s IRA leaders at gunpoint because of the IRA’s seizure of the IRF’s newsletter from the printer where it was being produced. The group also seized thousands of copies of the United Irishman, the Sinn Féin paper, as it arrived in the local railway station.

In the IRF publication, The Road To Revolution in Ireland, produced in 1966, it was argued that the republican nationalist current had to face “that the old approach to revolution wherein Republicans could rally a mass support for their efforts without the necessity of committing themselves to a social and economic programme of revolutionary proportions, no longer applied”. This marrying of the struggle of national liberation with the struggle of the working class was not a new current in the republican struggle, but one that was fully adhered to by the activists, like Jim Lane, within the Cork group, and carried with them in the membership of successor organisations. Relations between the group and the IRA were strained for much of the 1960s with the IRF regularly criticising the politics of the Republican Movement and arguing for a socialist way forward.

Jim Lane explained his relationship with Maoism as follows:

Sean Daly (ex IRA at the time) and myself met Hardial Bains and the other leaders of the Internationalists in 1968. .. We met with the intention of working together to build a Marxist-Leninist type party in Ireland. We certainly had a great issue with them about their methods of work in Ireland, among other matters. Suffice to say, we didn’t reach an agreement on the way forward. However, we did agree to remain in touch. Prominent in their group then and in the years that followed were; David Vipond, John Dowling, Arthur Allen and Carole Reekes. Hardial Bains of Indian birth was based in Canada.

As I may have said to you in our conversations last year, we were attracted to the line of the Chinese Communist Party, after we had studied the publication, The Polemic on the General Line of the International Communist Movement, (China, 1965). For us here in Ireland in the 1960s, we saw Mao and his party as advocates of armed revolutionary struggle, whereas the Soviet Union favoured the ’peaceful road to Socialism, by Parliamentary means’. Is it any wonder why Irish Socialist Republicans began to take an interest in the writings of Mao Tse-Tung back in the 1960s. Mythology has led many students of republican development in the 60s, to believe that all those who opposed ’the left-wing drift’, were ’right-wing red necks’. Not so, many who were conveniently referred to as ’Maoists’ within and without the Republican fold, were in fact those who were struggling to uphold true socialist revolutionary concepts.

In addition the Irish Revolutionary Forces established Saor Éire (Cork) in 1968 and produced a paper called People’s Voice. The Cork-based Saor Eire was largely made up of former IRA members, including several who had actively participated in the 1950s border campaign and were working-class left-republicans who moved towards Maoism in the mid to late 1960s. Saor Eire had contacts around Ireland, particularly among those republicans disaffected with the political drift of the Republican Movement. Members went north to ’help out’ when the ’troubles broke out at the end of the 1960s. “In fact”, Fintan Lane, an Irish labour historian, thought that “despite their Maoism, they were probably more connected to the Republican tradition than the orthodox communist tradition.”

Subsequently Jim Lane joined with others in forming the Cork Workers’ Club, which operated out of the same premises in St Nicholas Church Lane that Saor Éire had used since 1968 as its headquarters. The premises acted as a meeting place and bookshop which published a series of historical reprints of classic texts of Irish socialist republicanism, including James Connolly.

Jim Lane was central in the anti-H-Block movement in the Cork in the 1980s and became the chairperson of the Cork City and County National H-Block Committee. He joined Irish Republican Socialist Party becoming its national chairperson in 1983. He was influential in steering the Irish Republican Socialist Party/Irish National Liberation Army towards explicitly Marxist politics.

Lane was chief shop steward in Cash’s of Patrick Street, his place of employment for many years, until he retired in the 1990s. He stood unsuccessfully as an IRSP candidate in the 1982 general election, garnering a few hundred votes.

EROL thanks the Irish Left Archive for its work in making many of the following documents available on their website.

Miscellaneous Notes on Republicanism and Socialism in Cork City, 1954-1969 by Jim Lane

The Road to Revolution in Ireland by the Irish Revolutionary Forces

An Phoblacht A journal of the Irish Revolutionary Forces

On the Resignation of the Cork Branch of the Irish Communist Organisation by the Cork Communist Organization

On the IRA: Belfast Brigade Area by Jim Lane

Irish Socialists, Partition and the Struggle in the North

The Republican Movement and Socialism, 1950-1970 by Jim Lane

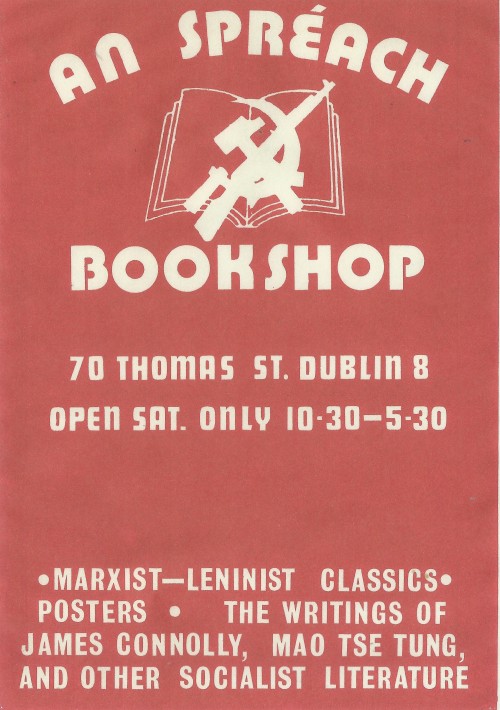

When the Communist Party of Ireland (ML) sided with the Albanians in the late 1970s, Maoism was pushed even further to the margins of the Irish political scene. Individuals may have been active in other political groups, but there was little chance of an encounter with organised Maoists outside of Dublin. At the start of the Eighties, however, The Finsbury Communist began advertising Marxist-Leninist publications from Ireland and China available from An Spreach book service, PO Box 965, 70 Thomas Street, Dublin 8 (Finsbury Communist, 188, September 1980).

An Spreach [The Spark], an Irish Marxist-Leninist group sent observers to the 2nd Congress of the Revolutionary Communist League of Britain. The RCLB’s Class Struggle reported in August 1981. “The comrade from An Spreach pointed to the connection between the Irish struggle and the struggle of the national minorities in Britain. She stressed that there were two organizations waging the armed struggle in Ireland and that both should be supported. She stressed the need for communists to involve themselves in the nationalist struggle that had as its strategic goal a united Ireland. She said that any possibility of work amongst the protestant section of the Irish working class was conditional on the defeat of British Imperialism in Ireland. In Ireland, the broad support for the Prisoners’ five demands contained the embryo of an anti-imperialist front. British revolutionaries must support the Irish people and not allow Thatcher to get away with murder.”

Apart from this intervention and a historic poster of James Connolly celebrating the 1916 Uprising which appeared in 1985, there has been little trace of any other activity on the part of this group.

The latest manifestation of Maoism in Ireland has been the World People’s Resistance Movement (Ireland), based in Dublin, which established a web presence going by the name “John Cornford” [wprmIreland.webs.com]. The WPRM (Ireland) has sided with the WPRM (Britain), reproducing articles opposed to the line of the Revolutionary Communist Party, U.S.A.’s “new synthesis”, and reposted the WPRM (Britain)’s The Criterion of Truth, which refers to the RCP,USA as a “completely failed and… grossly insignificant [group],” which “provides a good example of what not to do.”

Leading Light Communist Stand-In Line on Ireland

Nepal: The Martyrs Road: An Interview With An Irish Based Maoist On A Visit To Nepal (2006) by the World People’s Resistance Movement (Ireland)

Final Report: Nepal Visit 2009 by the World People’s Resistance Movement (Ireland)

First as Tragedy... by the World People’s Resistance Movement (Ireland)