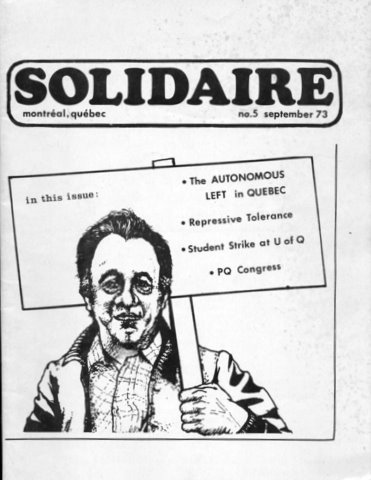

First Published: Solidaire, No. 5, September 1973.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Malcolm and Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

Over the last ten or so years in Quebec, numerous citizens’ and community groups have come into existence in order to deal with problems facing ordinary working people in their day-to-day lives. In the course of this process some individuals and groups have moved in a more political direction i.e. toward realizing that it is the economic and political structure of society as a whole that must be changed, rather than dealing solely with specific problems. This has led to the formation of various political groups and coalitions with differing ideas on what road to take toward a socialist Quebec.

Some of these groups with a clearer class analysis have come to the position that only an autonomous workers’ movement based directly on the organization of working people, where they work and live, can build a real socialism and a truly independent Quebec. This article focuses on the development of this latter position in the context of popular-based groups.

The article is divided into two major parts: the first deals with the development of the community and popular-based groups in the Montreal area; the second with similar organizations in the rest of Quebec. We felt that events inside and outside Montreal were usually different enough that it was better to deal with them in two sections. Montreal can easily be treated as a unit because of relatively high levels of communication between people and groups as well as often overlapping activities. Outside Montreal, struggles tend to be isolated from each other but they can be treated as a unit because they tend to happen under similar conditions. It should be realized that there has always been some level of communication between struggles in Montreal and in the rest of Quebec through the media, the union structure, personal contacts, and so on. Nonetheless the effects of this communication have been limited.

We consider that there are various limitations on this article as it stands. From reading it people could perhaps get the impression that the groups and tendencies we are talking about are stronger and more developed, both ideologically and numerically, than they actually are. The numbers of people in the groups discussed is relatively small. On the other hand, they are growing in both size and importance and they are just beginning the process of developing a clear analysis.

At times the article may seem general and sketchy. We sometimes lacked necessary information, particularly in terms of events outside Montreal. Most of our information has come from personal contacts and accounts published by the various groups involved. Published accounts often give no more than a group’s general and minimal consensus on an issue, rather than an account of the ideological and political struggles that led up to such a position. Finally, at times we felt it was necessary not to go into too great detail about specific events.

This article is an attempt to present and analyse a continuing process, and such an analysis is only just being developed by the groups involved here. We feel that the events we describe have significance not only for Quebec but for the practice of socialist movements elsewhere

Through the fifties and sixties, outside investment in Quebec’s economy, both American and Anglo-Canadian, grew at an ever-increasing rate. This growth created a demand from the big corporations for skilled technicians and managers that the existing Quebec educational system was not providing, and for a general modernization of Quebec society that would serve modern capitalist needs. The newly elected Liberal government (1960) instituted reform in all areas – government, social welfare policy, and education, among others – aimed at “bringing Quebec into the twentieth century”. One result of this so-called “Quiet Revolution” was a rapid expansion of educational opportunities for working people. Quebec’s “cheap labour” needed to be modernized like everything else. The government, meanwhile, began to develop an ideology of “citizens’ participation” and consultation in the solution of their immediate problems.

The period of 1963-68 saw the formation of community citizens’ groups (“groupes populaire”) in various “low-income” areas of Montreal. They were often formed on the initiative of “social animators” – social workers, sociologists, and other professionals – some of whom were paid by government welfare agencies. These people tended to be progressive members of the new professional petty bourgeoisie that was emerging from Quebec’s reformed universities, and often enough came from working class backgrounds themselves.

The animators saw poorer citizens being neglected by the government. Their goal was to give them a voice in determining their own living conditions. Usually their tactic was to set up programs that would help people recognize some of their immediate problems – poor housing, lack of leisure space, inadequate schooling and so on and involve them in finding solutions. They often worked in cooperation with the local petty bourgeoisie: clergy, small merchants, etc. As many of the animators were working class in origin, they genuinely hoped that conditions in their neighbourhoods could be qualitatively improved through these programs.

A number of small scale victories were won – a long-needed school was built in one area, a parking lot was converted to a childrens’ playground – and the number of citizens’ groups grew rapidly in working class districts of the city. But at the same time, frustration began to develop inside the citizens’ organizations for various reasons. People began to realize that a new school did not do much good if the quality of education inside it was still poor.

People in the groups, and some of the animators, began to question whether the solution of short-term,isolated problems could bring about any real qualitative change in people’s lives. They began to question the value of the citizens’ groups in their existing form. It became clear to many that ordinary people weren’t really gaining any influence on government policy, but only the possibility of consultation, and that depended on the whim of the government. People were coming up against the contradiction of attacking short-term and specific problems without dealing with the overall problem – the basically exploitative nature of capitalist society and the state’s role in maintaining that exploitation – although few people at the time were viewing things in precisely those terms.

Within the citizens’ groups, class differences began to show up. Working people realized in practice that their interests were not always the same as those of the petty bourgeois people involved. Not only did their interests differ from those of local establishment figures (clergy, merchants, etc.), but also more and more people gradually started to reject the professional, “social work” approach of the social animators. In a growing number of cases the two tendencies came into direct opposition, and this led to the formation of some separate “workers’ committees”. (It should be realized that these new committees were not made up mainly of “typical” workers, but were generally composed of young workers, students, and some petty bourgeois intellectuals already having a clear class analysis.)

Out of the frustration of the early citizens’ committees, these more militant people and groups tried to explain the general failure of the committees. They began to see the necessity of a more long-range political perspective on which to base their programs. At this stage – around 1967 – this involved a general criticism of the way the capitalist system operates, but without developing any clear alternative to it.

The first practical results of this developing analysis were the setting up of alternative structures which attempted to deal with peoples’ immediate needs while at the same time placing these needs in a political perpective. In various parts of the city one saw the establishment of food cooperatives, tenants associations, community health clinics and so on. Probably the best and most advanced example of this is Clinique St. Jacques, founded by the St. Jacques Citizens’ Committee in 1968 after aid was refused them by both the provincial and federal governments. The political purpose of the clinic was to create an awareness among people using its services that their health problems were related to the conditions in which they were living – poor housing, bad working conditions, inadequate schooling and so on. (See article in this issue.)

From the beginnings of citizens’ and workers’ organizations in Montreal, union militants had often had an important influence. Individuals active in the unions were often members of local community groups. By 1968 the union federations as a whole were becoming interested in social and political action outside of the usual limits of syndicalism. In the forefront of this move was the CSN (Confederation des Syndicats Nationaux – Confederation of National Trade Unions) with its “Second Front” – an attempt to organize around workers’ needs outside of the workplace. This and similar developments in the unions reinforced the tendency of union militants to play an important role in citizens’ and workers’ groups.

Between 1968 and 1970, discussions began among the citizens’ groups about co-operation and the possibility of forming some kind of wider political organization. CSN and other union militants in the groups were beginning to push strongly the idea of direct political action, along with militants who had previously been active in the student movement.

In the summer of 1970, the citizens’ committees, with financial and organizational help from the CSN, formed the Front d’Action Politique – FRAP (Political Action Front). It was to be a municipal party, primarily to run in opposition to Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau. This first political grouping of the citizens’ organizations took the form of a municipal opposition because it was Montreal’s unresponsive city government that had jurisdiction over most of the problems the citizens’ groups had tried to deal with – urban renewal, distribution of welfare services, and so on. The following is a statement of policies and goals reprinted from FRAP’s first newspaper: The Front d’Action Politique wants to bring democracy back to City Hall. For this reason, FRAP will run candidates for councillor in the October 25th municipal elections. FRAP wants to give salaried workers the place they deserve on the municipal council. Over 90% of the present councillors are professionals, businessmen and merchants, while 80% of the population is made up of salaried workers.

FRAP wants citizens to be aware of what is going on at City Hall.

The rest of the newspaper talked about what FRAP saw as Montreal’s five major problems: housing, health, social and economic development, transportation, and leisure and culture.

FRAP was a general umbrella structure made up of fourteen neighbourhood political action committees – CAPs (Comites d’Action Politiques). Six of these grew out of already existing citizens’ committees, but the rest were created expressely for the elections.

As a unit, the CAPs issued a document outlining their basic position:

In Montreal, the Workers Move on to Political Action

The ultimate goal of the CAPs is to create a society built on the will of the workers and based on priorities which they themselves establish. Our aims are:

1. to establish a real urban democracy in Montreal, based on the participation of workers on all levels of decision-making.

2. to allow the greatest number of workers possible to participate in the political life of Montreal.

3. to unite all workers in Montreal, whether unionized or non-unionized, unemployed or on welfare, tenants or students.

(n.b. We do not mean participation of the type offered by governments, but rather the kind a political organization of workers would allow.) We will refuse to participate in ways which will let us be controlled, or which would restrict our freedom.

Thus our present and future plans are to organize struggles in three areas:

1. in the area of consumer problems and co-operatives: housing, health, food, credit, etc. organize workers according to their immediate interests and needs.

2. in the area of work: salaries, working conditions, workers1 control in factories and offices, etc. Organize solidarity at work.

3. in the area of politics on the municipal level: Organize ourselves on the municipal level to make politics function in the interests of the majority. Check up on municipal candidates, run candidates in districts, confrontations through public meetings, etc.

Above all, FRAP stressed the necessity to expand the organization to include as many salaried workers as possible; through their programs, through the creation of new CAPs, and by concretizing their links with the unions.

Within the citizens’ groups that had developed directly into CAPs, FRAP had a good basis for establishing contact within the community. However, this meant that FRAP generally inherited the weaknesses of these communities – their tendency toward short-term, defensive actions against specific problems, and their lack of an overall political analysis. In the areas where CAPs were created primarily for the election, contacts within the community were weak.

Up until the October ’70 civic election, the dominant ideology in FRAP was reformist and did not make any real economic analysis of society. A pamphlet issued by FRAP in October ’70, entitled Power to Salaried Workers, discussed a series of social problems such as housing, transportation, health care and so on, without attempting to explain the causes of these problems. It emphasized the fact that only a small number of workers are in decision-making positions, whether at work, in their communities or at City Hall. It led to the conclusion that workers’ problems would be solved by electing more workers to positions of power.

FRAP at this time never went beyond attacking the secondary effects of capitalism, such as problems of consumption and the distribution of urban services within the context of the municipal elections. It was this political orientation which led away from an emphasis on workers’ struggles in the workplace or even in the community, and helped shape the internal structure of FRAP. Decisions on major actions tended to be made from the top down, and experience gained in these actions was not adequately passed on from most militants to the base. This situation parallels developments taking place in the unions with whom FRAP was forming strong ties and where the idea of a workers’ party, led by the union bureaucrats, was beginning to take shape.

The FLQ kidnapping crisis of October 1970 seriously weakened FRAP for the upcoming elections. The FLO manifesto had described in clear and concrete language the oppression and exploitation of Quebec’s workers by capitalism and imperialism. While disagreeing with the FLQ’s tactics, FRAP supported their general aims and the manifesto and condemned the “everyday violence of the capitalist system.” Both the federal government and Montreal mayor, Jean Drapeau, used this as an excuse to try to destroy FRAP’s credibility by accusing it of being no more than a front for the FLQ. Although there had been no possibility of a really big win for FRAP, the effect of this attack made sure that it did not win even one seat in the municipal government.

After the election, FRAP began to fall apart. Those CAPs created primarily for the election no longer had any basis for existence and dissolved. Within the remaining CAPs ideological splits became apparent. At FRAP’s second congress in the spring of 1971, ideological conflicts continued to manifest themselves. The congress adopted positions presented by CAP St. Jacques designed to change FRAP’s electoral, social democratic orientation; i.e. its tendency to favour large-scale, reformist struggles based on widespread propaganda, unrelated to the real strength of the movement and without any clear long-term strategy.

CAP St. Jacques’ intention was to rebuild FRAP from the base in line with a Marxist analysis. The propositions:

1. presented social problems as the manifestations of capitalism;

2. broke down FRAP’s base according to class ( production workers, service workers, unemployed, etc.)

3. designated the owners of the means of production ( i.e. the bourgeoisie ) as the primary enemy ’ thus changing the priority for action from the community to the workplace;

4. emphasized the development of active militants and their actual implantation in the various milieus;

5. favoured different types of decentralized local actions rather than large actions unrelated to the strength of FRAP.

The fact that these propositions came from CAP St. Jacques was significant. CAP St. Jacques was the largest CAP in terms of active militants and popular support in the elections. Because of its longer experience in community organizations, it could see more clearly the limitations of such action and the necessity of beginning to build a more solid base among working people.

Mainly because of CAP St. Jacques’ numerical superiority, their propositions were accepted by the congress. At the same time this did not reconcile the various positions within FRAP and the contradictions were becoming more divisive. CAP St. Jacques and CAP Maisonneuve ( another CAP with relatively strong support in its neighbourhood), began to focus their attention on the ideological development of militants working at the base. This was done in the context of a greater stress on actually having people at work in the factories and other workplaces (called in French “implantation”), and through more contact with local citizens’ organizations. At the same time they were beginning to work internally toward a better method of self-analysis and self-criticism.

The two CAPS were becoming less a part of FRAP and more a structure through which militants in different milieus could develop a political analysis based on what they were doing. In January, 1972, CAP Maisonneuve put out a document criticizing a fundamental FRAP working paper. In the working paper FRAP maintained that it was the structure providing unity and cohesion to workers and their struggles. However, it said this without assessing its actual strengths and limitations. Thus Maisonneuve felt that the paper expressed only in very vague terms how and on what basis unity should be built. Maisonneuve also thought that FRAP was assuming that there was unity of political orientation, without recognizing the real contradictions and divisions that exist within the working class (unionized vs. non-unionized, skilled vs. unskilled, men vs. women, etc. ). Basically, the division between CAP St. Jacques and Maisonneuve and the rest of FRAP was one of orientation – how do we build a socialist movement? FRAP saw itself as the workers’ party, while CAPs St. Jacques and Maisonneuve felt that the workers’ political organization should develop more organically out of the struggle at the base.

In March, 1972, at a debate on financial reorganization, CAPs St. Jacques and Maisonneuve split with FRAP.

Since the split in FRAP, elements in CAPs St. Jacques and Maisonneuve have developed criticisms of their handling of the whole affair.

At the Spring ’71 congress, CAP St. Jacques’ propositions were presented in a generally theoretical form and were not clearly enough related to the experience of FRAP’s members. Before the congress, CAP St. Jacques had neglected to adequately discuss their propositions with sympathetic members of the other CAPs, thus failing to win much potential support.

After the congress, CAPs St. Jacques and Maisonneuve failed to really develop an ideological struggle within FRAP around the new principles in an attempt to rebuild unity. As a result, the various CAPs continued in their own differing directions and the split of March ’72 became virtually inevitable.

As elsewhere, there are a number of sectarian groups in Quebec whose development is linked more closely to their affiliates outside Quebec than to any organic relationship with the community – as in the case of community action groups or citizens’ committees. (This is neither to oppose or support these groups, but just to point out an important difference.)

The two foremost such groups are the “Parti Communiste du Quebec (Marxiste-Leniniste)” and the Ligue Socialiste Ouvriere – Ligue des Jeunes Socialiste”, the first “maoist” oriented and the Quebec wing of the “CPC(ML)”, the second affiliated to the Trotskyist “League for Socialist Action”.

As elsewhere in Canada, the CPQ-ML sees itself as the vanguard party of the workers and bases all its actions on this role. It has little relationship with what is usually thought of as the left. Within the last two years CPQ-ML had a series of major splits, with several non-vanguard groups as a result.

The Trotskyists have also had several splits recently. However, as with the CPQ-ML, the main group continues to operate. It bases its actions on taking part in wider “mass movements” with a view to politicizing them. Thus it has continued as an active participant in the “Mouvement pour un Quebec Francais” (practically all other left groups have left it) and, as in Canada, is active in the abortion repeal movement.

The revisionist Communist Party of Canada continues to exist but is largely irrelevant, despite some connections in the unions.

At the present time, the activity of CAPs St. Jacques and Maisonneuve is directed toward developing organizations of workers controlled by workers and serving their needs. This is a progressive step toward the building of a socialist movement since many previous organizations had lacked contact with daily workers’ struggles, both in the workplace and in the community.

The first step in building this contact saw militants from the CAPs getting jobs, primarily in production, with the goal of helping to organize groups in the plants (“implantation”). Many of the militants were workers radicalized by their experience in citizens’ groups and their workplaces. Others,however, were from petty bourgeois intellectual backgrounds and had to face the difficulty of integrating into a work situation. All recognized the necessity of preferably working in large shops and realized that even beginning groups in their workplace would take a long time. Thus “implantation” was seen as a long-term process involving constant analysis and evaluation on the part of the militants involved.

St.Jacques and Maisonneuve recognized that there have been and continue to be militant workers’ struggles in Quebec, but these struggles generally centre on specific demands (salary, working conditions, unionization, etc.) and lack long-range political goals. Thus the purpose of “implantation” is to attempt to politicize existing workers’ groups and generate new ones.

At the same time, CAP militants are also working in various citizens’ groups such as tenants associations and health clinics, and in student groups.

Because implantation is only in its beginning stages, the CAPs have been faced with specific problems coming out of their inexperience. They have tended to single out prospective militants among the workers and brought them into the CAP, rather than working with them to form workers’ groups within the factory. This is a reflection of St. Jacques and Maisonneuve’s tendency to continually consolidate their own ideology without sufficiently sharing the lessons they have learned from their political experiences.

At the same time there is also the problem of coordinating the different sectors. Because militants are working in areas varying as widely as factories and health clinics, their experiences have been very different. This has often led to different conceptions of what tactics should be pursued. In the workplace, workers are most directly confronted with the reality of exploitation, ie. long hours, low pay, unsafe conditions, layoffs, speedups, and so on. Because workers in a given factory work under similar conditions and sometimes belong to a union, the awareness of the need to organize to defend their interests is more obvious. This differs from community work, e.g. tenants associations or health clinics, which deals with the secondary effects of capitalism and and depends on spreading propaganda in the context of providing a service. This tends to make militants involved in community work much more inclined toward mass work and wide-scale organizing while people working in factories tend to emphasize the building of concrete contacts with other production workers with related problems.

Community work is important in showing people that they can build alternative structures which they control and which serve their own needs. However, these structures run the risk of becoming just another service and can be coopted by the government unless they relate their service to the wider political context.

The difference in orientation created because militants are working in various sectors should not be taken as a black and white split, but forms part of the basis of much current debate in the CAPs on future strategy.

This debate over mass work and base organizing relates to the problem of defining the CAP as an organization. Should the CAPs, presently quite decentralized, attempt to build themselves into a strong organization, taking positions as a whole and intervening in situations; or should the organization itself be de-emphasized in favour of encouraging the formation of autonomous workers’ groups? This question remains to be resolved.

Though many local political groups call themselves “political action committees” (CAPs), the name does not imply any specific ideological position or strategy except a developing opposition to capitalism. After St. Jacques and Maisonneuve left, the other CAPs remained under the loose umbrella of FRAP. As their practice developed in their communities, they began to be more critical of FRAP.

FRAP involved itself in many struggles – but their were few victories. It concerned itself with issues such as transport and housing conflicts and tried to organize city-wide or sector-wide alliances (e.g. all the transport workers in the city). This was doomed to failure given the level of class consciousness at the time and FRAP’s lack of solid ties with these workers.

FRAP’s failures made it more apparent to many more of its militants that there would have to be a strong base before any work of this kind could be successful. This led to dissatisfaction with FRAP’s undefined ideology and its resulting undefined strategy. Several CAPs split from the organization and began to develop their own analysis and their own work, based on the specific needs of their communities. Many have come to some of the same conclusions as St. Jacques and Maisonneuve on the need for integration at the workplace(“implantation”), as have several newly formed CAPs which were never part of FRAP.

At this point there are few organizational ties between CAPs St. Jacques and Maisonneuve and the other CAPs which are independent of FRAP, despite their similar outlook. This is due on the one hand to a certain level of bad feeling and personality conflict dating from the split in FRAP, and on the other hand to the different stages the work of each CAP has reached.

In the past two years, partly due to mass confrontations such as the general strike and partly to anti-working class and anti-union reactions by the government, a number of autonomous workers’ groups have developed inside factories. By autonomous we mean small groups of workers who as a group are unaffiliated with any outside group or union. Some of these groups were aided by the work of militants from CAPs working in factories.

Because these groups are autonomous they can be critical of the unions and offer concrete proposals for contracts and changes in working conditions. They sometimes produce an internal newspaper concerned with directly mobilizing workers around specific issues in the plant. They stress democratization of the unions and control of the local unions from the base. The more developed groups are trying to relate these issues to the broader problems caused by capitalism outside the factories, and some have gained enough support in the plants to strongly influence their local unions.

In discussing political and community-based groups outside Montreal, we are not dealing with agricultural movements, but with small town and small city industrial movements. (It should be remembered that all of Quebec is industrialized, if in varying degrees; its industry being primarily extractive, processing, and light manufacturing.)

Small towns in outlying areas are usually dominated by one company which provides most of the employment. The economy of the entire town is dependent on the one company, which is invariably controlled by non-local interests, in many cases American. Decisions affecting the future of the company’s plant are made without regard for the welfare of the town. There is an increasing tendency for big corporations to close down unprofitable operations in outlying regions. Therefore, groups, composed of most citizens, are generally organized around the question of the plant and its survival because closure means disaster not just for the plant workers, but also for the entire town and surrounding area.

There are also industrialized cities and industrial parks located not far from Montreal or around important ports and hydro-electric projects. They occupy a position between highly urbanized Montreal and the small one-company towns, and thus their community and citizens’ groups exhibit characteristics of both these areas. Issues such as tenants’ and welfare rights, recreation facilities, and so on, are more independent from the primary issue of survival than they are in the small towns. With more sectors of their economy developed, the larger towns and cities lack the homogeneity of a central issue that unites all classes and needs.

Political organizations develop a bit differently outside of Montreal. Explicit political groups tend to come more directly out of labour struggles rather than the struggles of citizens’ groups. Also because such a large percentage of the people are unionized outside Montreal, citizens’ and popular groups are, themselves, highly influenced by union issues.

It is important to realize that the Parti Quebecois has been an important political force within unions and popular groups outside of Montreal. Before the general strike of May, 1972, the PO was supported by substantial numbers of union bureaucrats and rank-and-file. Union leadership, being in well-paid “professional” positions, share the technocratic petty-bourgeois outlook of the PQ. Rank-and-file union members, while not necessarily supporting all of the PQ programme, saw it, partly through the urging of their leaders, as a viable alternative to the Bourassa Liberal regime. With the general strike, however, many workers saw that the PQ could be just as anti-labour as the Liberal regime. The PQ anti-labour stance caused a backlash which stimulated the development of independent progressive political groups. This does not mean that all unionists and progressives left the PQ, as people still tried to influence the PQ convention of last April to more strongly represent workers’ interests.

We have chosen two examples of political development outside of Montreal to give a more concrete picture of the forms of organization, kinds of struggle, developing ideology, and contradictions found in Quebec. The first case is that of Mont Laurier, a one-company town. The second is that of Sept-Isles, which is the third largest port in Canada and has a variety of industry.

Mont Laurier is located in the Laurentian Mountains, 150 miles northwest of Montreal. The major industries of the area are pulp and paper, wood – and more recently, unemployment insurance and welfare. It is not heavily industrialized.

Mont Laurier has a long history of militant struggles involving solidarity among the CSN, FTQ and CEQ (teachers) unions. But if Mont Laurier workers show much solidarity among themselves, they seem isolated from workers in the rest of Quebec. For example, during the general strike of May 1972, participation here was quite weak and limited.

The major industry in Mont Laurier is the Dupan plant, which produces wood paneling. It has a most interesting history. In 1963 Dupan was sold to the government agency, SOGEFOR. Under SOGEFOR it was so badly mismanaged and maintained that the roof caved in once and there were two explosions leading to a total of five deaths and eight injuries. Despite Bourassa’s promise not to close down the plant, it was closed without warning in June, 1971. The government’s lack of response – 8,000 tons of raw material plus delicate machinery lay rotting while the government refused to allow buyers to see the plant – finally led the townspeople to barricade the highway. The government called in the riot squad.

The workers summed up their feelings about the affair in a manifesto:

Re-open Dupan

....above all, what concerns the workers of the Common Front is the availability of work: we want work, and work in our own factories.’ That is why we demand the immediate reopening of the Dupan and Dube (a sister plant) factories.

The employees have been out of work for three months already and we know it will take several weeks before the Dupan plant can be ready to operate. It is vital that measures are taken immediately to put the factory back into operation. Winter is approaching, and we refuse to suffer the misery of unemployment in winter.

In a region like ours, more unemployed is a tragedy. And 150 more is a catastrophe that will cause agony to the whole region.

How can the Bourassa government tolerate such a situation in a sector where they are directly responsible? It seems that their employment policy (“100,000 jobs”) is nothing but false promises.

However, at a higher level, what seems more serious to us, is the government’s abandoning of an agency whose goal was to give Quebec the means of taking its rightful place in the lumber industry. They are preparing to bury SOGEFOR; what did it die of? Malnutrition, criminal negligence, was it urged to suicide, or, more brutally, was it murdered? One thing is certain. With all the resources it is supposed to have, it is very strange that the government failed to support its child of the woods.

Did the government hold back in favour of private industry which did not want to see SOGEFOR grow? That seems evident, and symptomatic of the spirit that reigns in Quebec.

The employees of the Common Front of SOGEFOR are aware of the importance of the problem, not only for Mont Laurier, but for the future of the lumber industry in Quebec. The sabotage of SOGEFOR, intentional or not, is a definite backward step for Quebec in the search for its autonomy, especially in a sector so typically Quebecois: forestry.

Nevertheless, the Common Front has decided to continue the struggle until the Dupan and Dube plants are reopened. The Common Front will continue to inform the public about what is happening at SOGEFOR in Mont Laurier, so that they can follow more closely the waste of resources and the sabotage of a Quebec experience which might have been very worthwhile.

WE WILL WIN!

The Common Front of SOGEFOR,Sept. 1971 Reprinted from APLQ #30, pp.19-20.

Eventually an offer to buy the factory came from MacMillan-Blodell, a notoriously anti-labour company. In opposition to this offer, a coordinating committee of townspeople was formed to look into buying the plant. It consisted of the woodcutters’ union, the union of SOGEFOR workers in the plant, Citizen’s Committee of Mont Laurier, regional affiliates of the CSN, CEQ and the Union Catholique des Cultivateurs and various other popular associations. Their plan would be to sell shares to raise $400,000, half the money necessary to purchase the plant.

There is now a struggle between three tendencies over the financing of the remaining half of the required money. One group, consisting of members and supporters of the Parti Quebecois, the mayor of Mont Laurier, the local Chamber of Commerce, and some government officials, wants to raise the balance of the money from Quebec banks on the open market. Another group, made up of woodcutters and factory workers, wants to arrange cooperative financing, demanding that the workers control the factory. A third intermediary position, suggested by the provincial ministry of industry and commerce, was for financial involvement of the government which would “eventually” allow workers to “progressively retake” control of the plant.

What seems evident from the three positions is that even though the coordinating committee represents almost all elements of the town working together toward one objective, there are definite class contradictions within the group. The workers’ position, while accepting the fact that they have to pay for the plant, is progressive in the sense that they want to control the plant themselves and thus insure that they will have some control over their survival. On the other hand, the petty-bourgeois nationalists want the money and control to rest in Quebecois hands, but not necessarily those of the workers.

Mont Laurier shows the level of workers’ consciousness and militancy as well as the contradictions in their alliances with the local petty bourgeoisie and bourgeois nationalist forces (the PQ). The workers have learned that they cannot trust the government but must help themselves instead through their own organizations. Attempts have been made to do this through the formation of cooperatives, common fronts, etc. However, these organizations are dominated by bourgeois values and methods. Even if the workers succeed in buying and controlling the plant themselves, they will still have to operate within the bounds of the capitalist economy. This will mean quotas set from the outside, managers, and an “efficient” capitalist industry. In effect,’ a few of the financially ambitious workers would become small entrepreneurs (i.e. the administrators) and will have to recreate the organization of a capitalist industry in order to compete. The question of distribution of the returns is also not dealt with.

What happens to cooperatives has been shown time and time again in the development of the cooperative movement in Quebec, which is the strongest in North America. Cooperatives are invariably controlled by the petty bourgeoisie. Many of the cooperatives have reached a level of being important capitalist enterprises in the Quebec economy (and are just as alienating to work for).

Mont Laurier exemplifies some of the isolation and unfocused militancy of small towns in Quebec. Issues affecting the town as a whole channel workers’ needs and discontent into groups heavily influenced by other classes. The undeveloped class consciousness and the isolation from more political struggles in the industrialized centres accounts for much of this ideological confusion. As struggles develop with the worsening economic situation in these towns, class struggle within popular groups, like the Mont Laurier Dupan committee, will intensify.

Sept-Iles is an important port of about 35,000, situated 700 miles northeast of Montreal on the Gulf of the St. Lawrence. Its population doubled during the 1960’s as the result of rapid development of hydroelectric projects and iron-ore resources nearby. About 70% of the town is unionized.

In late 1970, the United Workers’ Front (FTU) was formed of CSN, FTQ, CEQ and many non-unionized workers. The FTU’s goal was to safeguard workers’ interests by watching over the government. Their major project was to prevent government land speculation by having the government sell the land to a town committee which would, in turn, sell it cheaply to the workers. The FTU would oversee the building and selling of these homes and insure that workers’ needs were being met.

Although the FTU began to develop contacts with political groups in Montreal, there was apparently no change in their orientation until the general strike in May, 1972.

During the general strike, Sept-Iles was the scene of some of the most militant action in Quebec. The town and radio station were seized and held until the occupiers were forcibly evicted (see Solidaire III). As the result of the action, committees made up of small shopkeepers, the chamber of commerce and other businessmen, were formed in opposition to the workers. This in turn resulted in a reply from the Common Front, which recognized the existence of class struggle in Sept-Iles:

We are fed up, Mr. Ryan

...The mercenary forces of Sept-Iles have chosen one of the most loyal spokesmen of our traditional elite, which every day betrays the most legitimate aspirations of the workers.

The Common Front of Sept-Iles denounces the initiative of the do-gooders and the steps taken by the establishment to see that the editorialist of the Devoir [the Devoir is an intellectual left-liberal Montreal paper edited by Claude Ryan, a well-known and influencial analyst] comes here to preach peaceful co-existence between groups, class collaboration, obedience and slavery.

We are fed-up, Mr. Ryan, with respecting laws that crush the people in the name of an order defined by the rich.

In Quebecois society today, you cannot play on both sides; you have to choose which side to fight on. We are warning the workers of Sept-Iles and Quebec against the bewildered theologians of Quebec’s political and social life, against a representative of our traditional elite like Claude Ryan, propagandist of the established law and order, against such a poor defender of the social and national struggle of Quebec, since he has not committed himself to one side or the other.

The struggles, real or underhanded, that it seems Mr. Ryan wants to lead against the Trudeaus and the Bourassas cannot mask his natural tendencies toward the status quo in Quebec and his disdain for the working class which, itself, leads a struggle for worldwide liberation.

(APLQ # 66, 1-2)

Though there may be workers who recognize the need for struggle on a class basis (unlike Mont Laurier) there is no agreement on how to carry this out. At a regional convention of the teachers’ union, a group of Sept-Iles teachers walked out, with complaints that the convention was not justly responding to their propositions iconcerning local action, etc:

Toward a New Orientation

During the course of intensive preparation, it became clearly apparent to the Sept-Iles delegation that action for the following year should be oriented toward socio-political objectives. The past several months of struggles have shown us, as well as many others,(whether they are the majority or not) that traditional unionism is no longer good enough. Not to engage in a fundemental reform of society is to leave the organization of our society in the hands of others (the rulers and exploiters) for their own profit. They in turn give us, in collective bargaining, only the crumbs from their table.

This socio-political action requires the decentralization of union activities. There are two reasons for this. First, because it would be illogical, and even criminal, for the unions, in the name of human dignity, to claim more power for the workers and independence in opposition to the bosses and the state while at the same time keeping their members in a feudal or police-type of structure. Secondly, even though it is sometimes important to mobilize all forces for conflicts on the national level, it is no less important that the struggle try to achieve immediate results in each region. In Sept-Iles, these objectives are quite evident, since the enemy imposes his power with such offhandedness that he appears in hideous clarity. In opposition to this, the workers (70% of the population is unionized) form such a group that one can hope to obtain major results by mobilizing them. Therefore, the teachers of SEN [the teachers’ federation in Sept-Iles] have bitter memories of provincial negotiations that have frozen their salaries since 1964, that have lost their cost-of-living and moving bonus, as well as a crowd of other acquired rights.

The delegates from Sept-Iles, therefore saw the obligation to strongly underline the importance of social action at the same time as stressing a redesign of the union structure to meet the new objectives. They did not go to the congress with the intention of electing or re-electing such and such a member, but with the intention of choosing from among all those at the congress, the persons most likely to act on the major positions of the congress. Perhaps a little idealistic and naive, but justifiable when one counts on others good faith. We came in good faith....

Our griefs in respect to the SEN also apply, with some slight differences, to the CEQ [Quebec Teachers’ Union).

We blame it also for its rigid centralist structures, its lack of clarity about its objectives, and its election structure which degenerates to backstage manoeuvers and political deals.

Centralized structures, on the model of Sun Life insurance and other capitalist monsters; centralization of personnel, of money, of projects; it is necessary to leave much more to local initiatives.

Lack of clarity on objectives: the CEQ, for example, fought for urgent but secondary objectives; conditions of work,salaries; it exhausted itself by bargaining for a collective aggreement which included a multitude of clauses which, by their large number alone, transforms relations between teachers and bosses into a nightmare. With such a situation, neither of the two parties has enough free time to seriously work on such things as teaching....

(APLQ # 68, p. 13)

Although the document points out many of the contradictions of the union movement – its defensive position, its bureaucracy and its role of integrating workers into capitalism – it also shows basic tendencies, toward concentration on local issues and local control, to the detriment of solidarity among workers. In this way, it also fails to tie teachers into workers’ struggles as a whole.

One of the most important tendencies in Sept-Iles now, which is quite similar to Quebec City, St. Jerome and Hull, is the recent development of a CAP (political action committee).

We here show two reprints from the journal printed by the CAP, the first from issue #1 in October, 1972, and the second from issue #2 in March, 1973. There is quite an obvious difference between the two styles of writing, and the subject matter. October was election time, and that was what the issue aimed at. In March, however, the CAP had apparently decided that one of its tasks was to combat reformist unionism and to put unions into a broader Marxist context. We have very little idea of what went on in the CAP in this time period, how it was received, what sort of workers are in it, etc. However, we present these reprints as concrete evidence to the type of ideological struggle going on on one level in Sept-Iles. Following it is a reprint from a worker-oriented St-Jerome paper that has been in existence for over a year. It indicates the kind of relations existing between the paper and its milieu.

Sept-Iles and Mont-Laurier show many of the characteristics of struggles going on outside Montreal. Mont-Laurier, being dependent for its survival on the Dupan plant, is very much the model of many small towns. The same defensive struggle against closings is occurring in Cabano, Cadillac, Temiscaming, etc. Within the movement to defend the town there exist conflicting class interests which are subordinated to the primary issue of economic survival. The merchants and Chamber of Commerce, as well as the workers, are dependent on the plant. The workers in these small towns are in different stages of development but the workers of Mont-Laurier indicate the level of militancy that can exist among workers in spite of a lack of their own strong autonomous organizations. As well, as the struggles in small areas develop, there will also develop more contact with the more advanced industrial centers. This will help break down the isolation and lack of ideology of places like Mont-Laurier.

Sept-Iles shows a more advanced stage of development of the workers’ movement. It is less isolated than many other remote industrial areas because so many of its workers are from Montreal. Industrial cities, like Sept-Iles, follow more closely a development similar to that of Montreal, from citizens’ committee-type organizations to political groups, except that outlying citizens’ committees are much more tied into the union movement. Because these cities have many plants and secondary industries, we find the growth of regional and local common fronts that tie together workers’interests in different plants These groups involve different levels of workers and union officials, as well as influences from the P.Q. However, the interests of workers, as opposed to those of the merchants and bankers, is more clearly defined than in small towns like Mont-Laurier.

Within the workers’ movement in places like Sept-Iles there are different levels of political consciousness. For example, many workers took part in the general strike only because their unions were participating not because of any principled commitment. Some of the local papers and documents develop positions far to the left of the P.Q. but still see it as their party because often there is little else in terms of a political force.

There are different levels of struggle outside Montreal but there is a growing interchange of information and experience between citizens’ groups and political groups across Quebec. These seeds of political groups are crucial in giving direction to the high militancy and growing struggles continuously developing outside Montreal.

In past Solidaires we discussed two of the basic forces of opposition in Quebec – the union movement and the Parti Quebecois – and tried to present their limitations. This issue has talked about various political groupings that have developed over the last few years out of the many community-based groups that exist in Quebec. In our opinion, the most significant tendency among these groups, both inside the Montreal area and in the rest of Quebec, is aimed at the construction of an autonomous workers’ movement – independent of both the unions and the PQ, and based on the organization of workers in the workplace and the community. This tendency is gradually developing towards a position that a truly socialist and independent Quebec can only be created through a revolution led by the working class, that will destroy both capitalism and imperialist domination. But this position is only in its embryonic stages and is only one of those influencing the Quebecois workers.

The influence of the union movement has become increasingly important due to the growth of militancy over the last few years. Although the unions have taken a step in the right direction by seeing the struggle of the workers in political terms and realizing that fighting on purely economic grounds usually gets them nowhere, they are unable to formulate a coherent strategy to bring about social change. They have attempted to transcend union divisions, as can be seen by the Common Front in the public sector, but these efforts have met with limited success. Inter-union rivalries continue, sometimes quite viciously (e.g. in the construction industry).

Despite the growth of militancy, there are contradictions in the union structure itself that have prevented the unions from developing into organizations that can fight for real economic and political power for the working class. The split between union leaders and the rank and file is such that leaders, who are paid by the unions, no longer experience the direct oppression and exploitation of wage slavery. Their bosses are the unions, not companies. Thus they don’t share the experiences of the workers they are negotiating for. The leadership has too much invested in the existence of unions as they are to become revolutionary.

The basic function of the unions is to fight for higher wages and better conditions within the capitalist structure. No matter how unwillingly, the unions serve to integrate the workers into the system, and to control conflict between classes. This is not to say that the unions in Quebec have not recently provided a framework for a certain level of politicization and organization of workers. This is likely to continue and may be very important, especially in certain locals, in particular workplaces. But nonetheless, no matter how radical the unions may become, their structure and activity prevents them from being the framework for revolutionary organization.

The “left” of the union bureaucracy, as can be seen in their close connections with FRAP, are looking for “socialism through negotiation”. Their orientation seems to be one of getting a “better deal” for workers and changing the system from within. They tend to support the idea of a union-based electoral “workers’ party”. They want workers in office, higher wages, “workers’ control”, an independent Quebec, citizens’ participation in government, and so on. They are very unclear about the means of destroying capitalism, and of building socialism.

It is precisely this lack of direction of the unions that has led some unionists into a friendship with the Parti Quebecois – if a somewhat uneasy one. Many union bureaucrats see the PQ as more democratic than the other parties, and therefore more responsive to the needs of the workers. They see the PQ as the most realistic choice of the opposition forces because it is the best organized and has the best chance of gaining power.

In reality, the PQ has not shown itself to be a friend of the workers in times of crisis, but rather has joined the other parties in condemning worker militancy, breaking strikes, and supporting anti-union legislation. This can be seen in the PQ’s reactions to the LaPresse conflict and the May ’72 General Strike (see Solidaire 3). At most, the PQ talks about “humanizing capitalism”. It denies class struggle through the use of radical-sounding nationalist rhetoric. The image of being flexible, progressive, and democratic that they have created for themselves has attracted many progressive people. Many still remain, even after the PQ has begun to show its true nature. This is especially true outside Montreal, where there are fewer left alternatives.

The PQ is quite firmly controlled by the petty bourgeoisie, who desire a planned “humanized” capitalist Quebec; independent of Canada. Continued attempts to influence the party in a left direction have failed. (See article in this issue, and Solidaire 4) Workers are becoming more aware that the PQ is basically a bourgeois nationalist party, but nonetheless, it still exerts a lot of influence among the working class.

It is in the light of the limitations of the unions and the Parti Quebecois that independent leftist forces have emerged. We have shown in this article the origins of this tendency and the struggles associated with the development of an autonomous workers’ movement. There remain many problems to be overcome and questions to be resolved.

A major obstacle is the isolation and lack of unity between the various working class oriented groups – the Comites d’Action Politiques, the workers’ committees, etc. This isolation is accentuated outside of Montreal. At the same time there is an increasing debate within the CAPs about what their role should be, particularly with the growing number of workers’ committees and groups that are independent of or only vaguely connected with the CAPS. There are those who feel that the role of the CAPs as organizations giving direction should be downgraded and that the emphasis should be laid on building links between organized groups of workers in the factories and other workplaces. This position tends to be held by people already in workplace situations who see the CAPs as transitional organizations that could quite well disappear as working class organization increases at the base. On the other hand, there is a tendency among people working in community organizations to favour a stronger and more concrete political leadership from the CAPs. Another question inside the CAPs that must be dealt with is the petty bourgeois background of many of the militants and the isolation from the mainstream of the working class that can often result from it.

The most important debate at present is over what direction the movement should take: how should an autonomous organization of the working class be built? There are some militants who feel that the priority should be the development of an ideological consensus between the various groups (e.g. via a newspaper) as a prerequisite to the building such an organization. Others say the priority is the continued organization and consolidation of workplace and other base-level groups, and that although wider level propaganda work is necessary it must be closely linked and coordinated with the primary task of organization at the base. This debate is only beginning and the two alternatives given are just approximations of peoples’ varying positions, but the fact that this discussion has started shows the growing consciousness of the need for a revolutionary strategy and unity among the working class movement in Quebec.