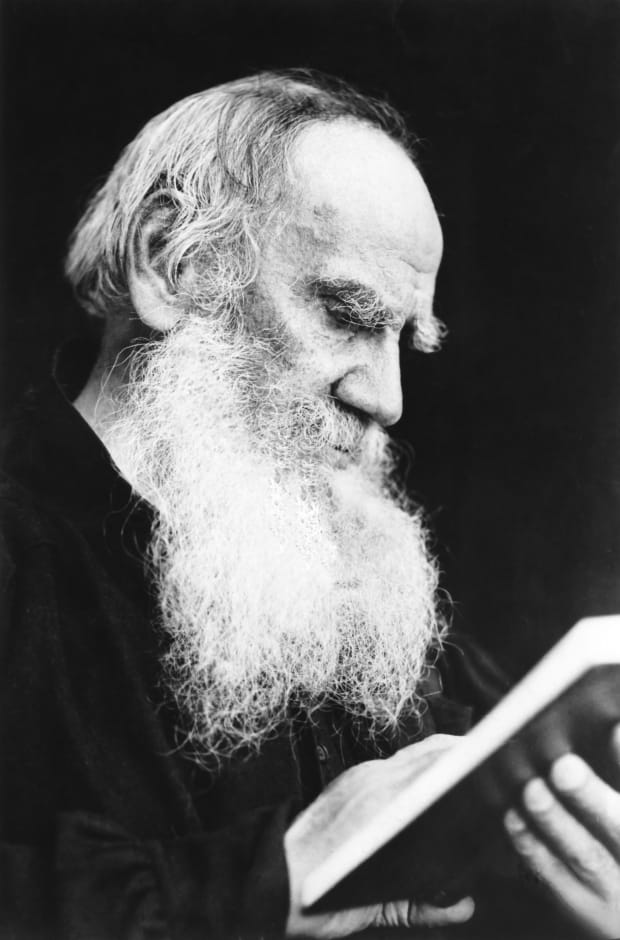

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1908

Source: From RevoltLib.com

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

It is far more natural to conceive of a society of people governed by reasonable, advantageous laws, that are recognized by everyone, than of the society in which people live today, obeying only violence.

The man who has not yet awoken to the truth sees political power as various sacred institutions, like the organs of a living body forming the essential conditions of life. For the man who has awakened to the truth, these people appear very mistaken, for they have attributed to themselves some kind of fantastic significance without any rational justification for it, and they fulfill their desires through violence. The awoken person also regards the lost and for the most part bribed people doing violence to other people just as highway robbers, who grab people on the road and violate them. The antiquity, scale and organization of violence cannot alter the nature of the deed. The man awakened does not believe in the thing called the State and sees no justification for all the acts of violence performed in the name of the State: therefore he cannot participate in them. State violence is eradicated not as a result of external factors, but only through the awareness of those who have woken to the truth.

Perhaps political violence was necessary to man’s former existence, perhaps it is still necessary now, but people cannot help seeing, and foreseeing, a way of life where violence can only interfere with peaceful existence. And, seeing and foreseeing this, people cannot help striving to realize such an order. And the means of realizing it lie in inner perfection and nonparticipation in violence.

‘But how can we live without a government, and without authority? People have never lived this way,’ is the retort to this.

People are so accustomed to the political structure in which they live that to them it seems an unavoidable, everlasting form of human existence. But it only seems so: people have lived, and do live, outside the political structure. All the primitive peoples who have not yet reached what we call civilization have lived and still live in this way. So also do people who have reached an understanding of life that is higher than civilization: Christian communities exist in Europe, in America and particularly in Russia, where the members have rejected the State; they feel no need of it and only put up with interference from it, when they cannot avoid doing so.

The State is only a temporary thing and in no way a permanent feature of human life. Just as the life of an individual person is not static, but is continually changing, moving forward and perfecting itself, so too the life of the whole of humanity does not cease to change, to move on and perfect itself. Each separate individual has at some point in his life drunk from his mother’s breast, played with toys, studied, worked, married, raised children, freed himself from passion and grown wiser with age. And the life of a nation grows wiser and perfects itself in the same way, only not within a period of years, as with people, but over the course of centuries and millennia. As with people, the main changes occur in the spiritual, invisible realms, so too with humanity the main changes occur, first and foremost, in the invisible sphere of religious consciousness.

And just as in the individual these changes take place so gradually that it is never possible to pin-point the hour, the day or the month when a child ceased to be a child and became a youth and then a man, we nevertheless know for certain once this transition has occurred. Likewise we can never pin-point the period when humanity, or a particular part of it, has outlived one religious age and entered into another one. But just as we know that the former child has become a youth, we know that humanity, or a part of it, has outlived one period of religious growth and entered into another, higher one, once the transition has taken place.

This sort of transition from one period of human development to another is ocurring today in the life of the Christian nations.

We do not know the hour when a child becomes a youth, but we know that the former child no longer plays children’s games. Similarly we cannot name the year, nor even the decade, when the Christian world passed from its earlier form of life and entered another age, distinguished by its religious awareness, but we cannot help knowing and seeing that the people of the Christian world can no longer seriously play at war games, monarchical audiences, diplomatic artifice, or at constitutions with chambers and dumas, or at party politics whether socialist-evolutionary, democratic, anarchic, or revolutionary. And, above all, we cannot continue to do all these things, basing them on violence.

This is especially noticeable now here in Russia with our outer changes in the political structure. The serious-minded Russian people can now no longer help feeling towards all the new forms of government that have been introduced, as an adult would feel if he were given a new toy, that he had not possessed as a child. However new and interesting the toy may be, he does not need it and can only regard it with amusement. This is how it is with us in Russia; it is the attitude all thinking men, as well as the vast masses of the population, have towards our constitution, the Duma, the various revolutionary parties and unions. Although it is not obvious, I believe I am not mistaken in saying that the Russian people of our time can no longer seriously believe that man’s vocation in this life is to employ the short interval allotted him between birth and death in making speeches in the chambers, or to gatherings of Socialist comrades, or in judging one’s neighbors in law courts, or in capturing, imprisoning and murdering them, or in throwing bombs and seizing their land; nor in worrying about whether Finland, India, Poland and Korea can be made part of what is called Russia, England, Prussia, Japan; nor in liberating these countries by force and being prepared for mass murder of one another. A man of our times cannot, in the depths of his soul, help recognizing the absurdity of all these activities.

The only reason we fail to see the full horror of the life we lead, so contrary to human nature, is because all the horrors in the midst of which we quietly live have crept in so gradually that we have failed to notice them. It befell me in the course of my life to see a neglected old man in the most dreadful state: his body was teeming with worms, he could not move a single limb without suffering, yet he did not realize the full horror of his predicament because it had crept upon him so imperceptibly. He asked only for tea and sugar. The same happens in our lives: we do not see the horror simply because the approach to the situation has been made with such quiet little steps that we do not notice the full extent of the horror, but simply take pleasure in new cameras and motor cars, as the old man took pleasure in tea and sugar. Apart from the fact that there is nothing to lead us to suppose that the abolition of violence men use against each other and which is so contradictory to reasonable, loving human nature, would worsen rather then ameliorate the human predicament, apart from that society’s present condition is so utterly dreadful that it would be hard to imagine anything worse.

Therefore, the question of whether people can live without governments is not frightening, whatever way the defendants of the existing order like to imagine it, but it is as farcical as it would be to ask a tortured man how he would live if they were to stop torturing him.

People who stand in exclusively privileged positions, as a result of the existing political structure, impose an opinion that people without government would be in tremendous strife and that everyone would be at war with everyone else. It is just as if they were speaking of the co-existence not of animals (animals live peacefully without any political coercion) but of some dreadful creatures whose behavior is governed by nothing except hatred and madness. But they only paint people to be like this because they attribute to them qualities contrary to their nature, but which have been nurtured by that very same governmental structure under which they themselves have grown up and which they continue to support, despite its being absolutely unnecessary and harmful.

Therefore, to the question of what life would be like without government and authorities, the answer can only be that there would certainly not be all the evil which government creates. There would be no private landownership, no taxes spent on things needless to people, no division of nations, no enslavement of some by others, no more wastage of the best human resources on war preparation, no more fear of the bombs on the one hand, of the gallows on the other; and there would be none of the insane luxury of some, and still more insane poverty of others.