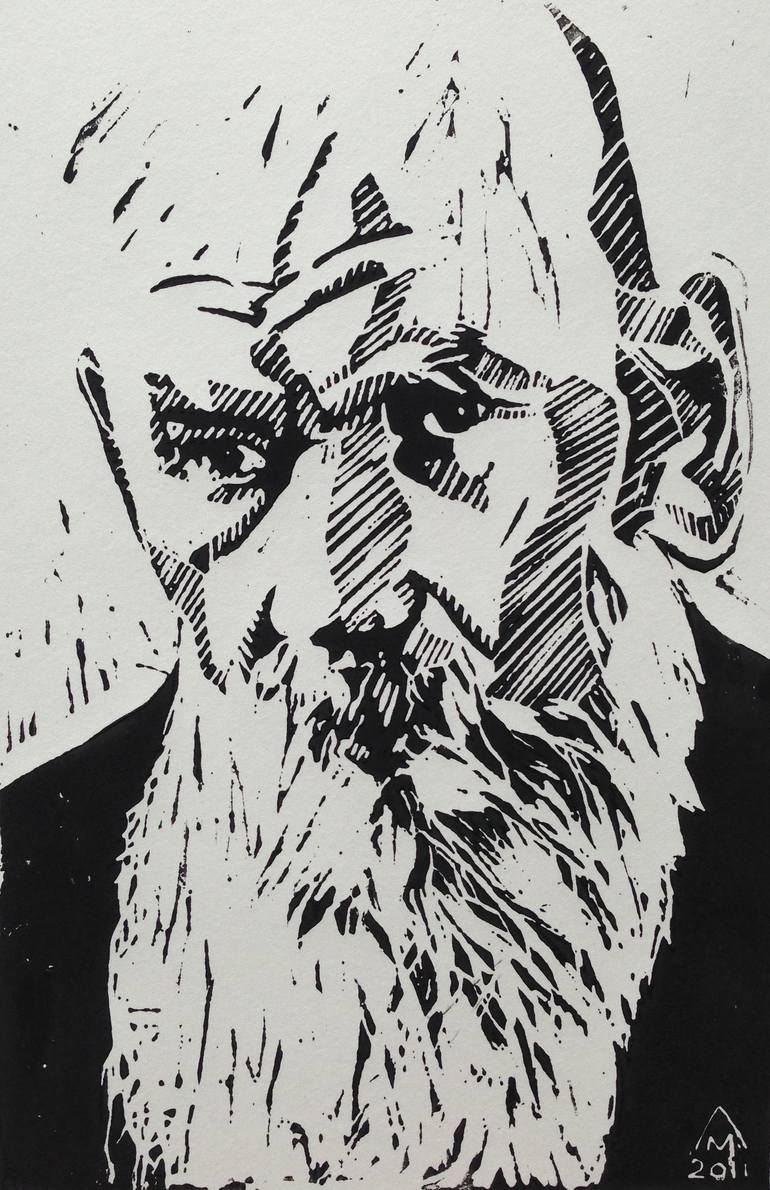

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1899

Source: Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy, translated from Russian to English by Constance Clara Garnett

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

The justiciary finally finished his speech and handed the list of questions to the foreman. The jury rose from their seats, glad of an opportunity to leave the court-room, and, not knowing what to do with their hands, as if ashamed of something, they filed into the consultation-room. As soon as the door closed behind them a gendarme, with drawn sword resting on his shoulder, placed himself in front of it. The judges rose and went out. The prisoners also were led away.

On entering the consultation-room the jury immediately produced cigarettes and began to smoke. The sense of their unnatural and false position, of which they were to a greater or less degree cognizant, while sitting in the court-room, passed away as soon as they entered their room and lighted their cigarettes, and, with a feeling of relief, they seated themselves and immediately started an animated conversation.

"The girl is not guilty, she was confused," said the kindhearted merchant.

"That is what we are going to consider," retorted the foreman. "We must not yield to our personal impressions."

"The judge's summing up was good," said the colonel.

"Do you call it good? It nearly sent me to sleep."

"The important point is that the servants could not have known that there was money in the room if Maslova had no understanding with them," said the clerk with the Jewish face.

"So you think that she stole it?" asked one of the jury.

"I will never believe that," shouted the kindhearted merchant. "It is all the work of that red-eyed wench."

"They are all alike," said the colonel.

"But she said that she did not go into the room."

"Do you believe her more than the other? I should never believe that worthless woman."

"That does not decide the question," said the clerk.

"She had the key."

"What if she had?" answered the merchant.

"And the ring?"

"She explained it," again shouted the merchant. "It is quite likely that being drunk he struck her. Well, and then he was sorry, of course. 'There, don't cry! Take this ring.' And what a big man! They said he weighed about two hundred and fifty pounds, I believe."

"That is not the point," interrupted Peter Gerasimovich. "The question is, Was she the instigator, or were the servants?"

"The servants could not have done it without her. She had the key."

This incoherent conversation lasted for a long time.

"Excuse me, gentlemen," said the foreman. "Let us sit down and consider the matter. Take your seats," he added, seating himself in the foreman's chair.

"These girls are rogues," said the clerk, and to sustain his opinion that Maslova was the chief culprit, he related how one of those girls once stole a watch from a friend of his.

As a case in point the colonel related the bolder theft of a silver samovar.

"Gentlemen, let us take up the questions," said the foreman, rapping on the table with a pencil.

They became silent. The questions submitted were:

1. Is the peasant of the village of Barkoff, district of Krapivensk, Simon Petroff Kartinkin, thirty-three years of age, guilty of having, with the design of taking the life of Smelkoff and robbing him, administered to him poison in a glass of brandy, which caused the death of Smelkoff, and of afterwards robbing him of twenty-five hundred rubles and a diamond ring?

2. Is the burgess Euphemia Ivanovna Bochkova, forty-seven years of age, guilty of the crime mentioned in the first question?

3. Is the burgess Katherine Michaelovna Maslova, twenty-seven years of age, guilty of the crime mentioned in the first question?

4. If the prisoner Euphemia Bochkova is not guilty of the crime set forth in the first question, is she not guilty of secretly stealing, while employed in the Hotel Mauritania, on the 17th day of January, 188—, twenty-five hundred rubles from the trunk of the merchant Smelkoff, to which end she opened the trunk in the hotel with a key brought and fitted by her?

The foreman read the first question.

"Well, gentlemen, what do you think?"

This question was quickly answered. They all agreed to answer "Guilty." The only one that dissented was an old laborer, whose answer to all questions was "Not guilty."

The foreman thought that he did not understand the questions and proceeded to explain that from all the facts it was evident that Kartinkin and Bochkova were guilty, but the laborer answered that he did understand them, and that he thought that they ought to be charitable. "We are not saints ourselves," he said, and did not change his opinion.

The second question, relating to Bochkova, after many arguments and elucidations, was answered "Not guilty," because there was no clear proof that she participated in the poisoning—a fact on which her lawyer put much stress.

The merchant, desiring to acquit Maslova, insisted that Bochkova was the author of the conspiracy. Many of the jurymen agreed with him, but the foreman, desiring to conform strictly to the law, said that there was no foundation for the charge of poisoning against her. After a lengthy argument the foreman's opinion triumphed.

The fourth question, relating to Bochkova, was answered "Guilty," but at the insistence of the laborer, she was recommended to the mercy of the court.

The third question called forth fierce argument. The foreman insisted that she was guilty of both the poisoning and robbery; the merchant, colonel, clerk and laborer opposed this view, while the others hesitated, but the opinion of the foreman began to predominate, principally because the jury were tired out, and they willingly joined the side which promised to prevail the sooner, and consequently release them quicker.

From all that occurred at the trial and his knowledge of Maslova, Nekhludoff was convinced that she was innocent, and at first was confident that the other jurors would so find her, but when he saw that because of the merchant's bungling defense of Maslova, evidently prompted by his undisguised liking for her, and the foreman's resistance which it caused, but chiefly because of the weariness of the jury, there was likely to be a verdict of guilty, he wished to make objection, but feared to speak in her favor lest his relations toward her should be disclosed. At the same time he felt that he could not let things go on without making his objections. He blushed and grew pale in turn, and was about to speak, when Peter Gerasimovich, heretofore silent, evidently exasperated by the authoritative manner of the foreman, suddenly began to make the very objections Nekhludoff intended to make.

"Permit me to say a few words," he began. "You say that she stole the money because she had the key; but the servants could have opened the trunk with a false key after she was gone."

"Of course, of course," the merchant came to his support.

"She could not have taken the money because she would have nowhere to hide it."

"That is what I said," the merchant encouraged him.

"It is more likely that her coming to the hotel for the money suggested to the servants the idea of stealing it; that they stole it and then threw it all upon her."

Peter Gerasimovich spoke provokingly, which communicated itself to the foreman. As a result the latter began to defend his position more persistently. But Peter Gerasimovich spoke so convincingly that he won over the majority, and it was finally decided that she was not guilty of the theft. When, however, they began to discuss the part she had taken in the poisoning, her warm supporter, the merchant, argued that this charge must also be dismissed, as she had no motive for poisoning him. The foreman insisted that she could not be declared innocent on that charge, because she herself confessed to giving him the powder.

"But she thought that it was opium," said the merchant.

"She could have killed him even with the opium," retorted the colonel, who liked to make digressions, and he began to relate the case of his brother-in-law's wife, who had been poisoned by opium and would have died had not antidotes promptly been administered by a physician who happened to be in the neighborhood. The colonel spoke so impressively and with such self-confidence and dignity that no one dared to interrupt him. Only the clerk, infected by the example set by the colonel, thought of telling a story of his own.

"Some people get so accustomed to opium," he began, "that they can take forty drops at a time. A relative of mine——"

But the colonel would brook no interruption, and went on to tell of the effect of the opium on his brother-in-law's wife.

"It is five o'clock, gentlemen," said one of the jury.

"What do you say, gentlemen," said the foreman. "We find her guilty, but without the intent to rob, and without stealing any property—is that correct?"

Peter Gerasimovich, pleased with the victory he had gained, agreed to the verdict.

"And we recommend her to the mercy of the court," added the merchant.

Every one agreed except the laborer, who insisted on a verdict of "Not guilty."

"But that is the meaning of the verdict," explained the foreman. "Without the intent to rob, and without stealing any property—hence she is not guilty."

"Don't forget to throw in the recommendation to mercy. If there be anything left that will wipe it out," joyfully said the merchant. They were so tired and the arguments had so confused them that it did not occur to any one to add "but without the intent to cause the death of the merchant."

Nekhludoff was so excited that he did not notice it. The answers were in this form taken to the court.

Rabelais relates the story of a jurist who was trying a case, and who, after citing innumerable laws and reading twenty pages of incomprehensible judicial Latin, made an offer to the litigants to throw dice; if an even number fell then the plaintiff was right; if an odd number the defendant was right.

It was the same here. The verdict was reached not because the majority of the jury agreed to it, but first because the justiciary had so drawn out his speech that he failed to properly instruct the jury; second, because the colonel's story about his brother-in-law's wife was tedious; third, because Nekhludoff was so excited that he did not notice the omission of the clause limiting the intent in the answer, and thought that the words "without intent to rob" negatively answered the question; fourth, because Peter Gerasimovich was not in the room when the foreman read the questions and answers, and chiefly because the jury were tired out and were anxious to get away, and therefore agreed to the verdict which it was easiest to reach.

They rang the bell. The gendarme sheathed his sword and stood aside. The judges, one by one, took their seats and the jury filed out.

The foreman held the list with a solemn air. He approached the justiciary and handed it to him. The justiciary read it, and, with evident surprise, turned to consult with his associates. He was surprised that the jury, in limiting the charge by the words, "without intent to rob," should fail to add also "without intent to cause death." It followed from the decision of the jury, that Maslova had not stolen or robbed, but had poisoned a man without any apparent reason.

"Just see what an absurd decision they have reached," he said to the associate on his left. "This means hard labor for her, and she is not guilty."

"Why not guilty?" said the stern associate.

"She is simply not guilty. I think that chapter 818 might properly be applied to this case." (Chapter 818 gives the court the power to set aside an unjust verdict.)

"What do you think?" he asked the kind associate.

"I agree with you."

"And you?" he asked the choleric associate.

"By no means," he answered, decidedly. "As it is, the papers say that too many criminals are discharged by juries. What will they say, then, if the court should discharge them? I will not agree under any circumstances."

The justiciary looked at the clock.

"It is a pity, but what can I do?" and he handed the questions to the foreman.

They all rose, and the foreman, standing now on one foot, now on the other, cleared his throat and read the questions and answers. All the officers of the court—the secretary, the lawyers and even the prosecutor—expressed surprise.

The prisoners, who evidently did not understand the significance of the answers, were serene. When the reading was over, the justiciary asked the prosecutor what punishment he thought should be imposed on the prisoners.

The prosecutor, elated by the successful verdict against Maslova, which he ascribed to his eloquence, consulted some books, then rose and said:

"Simon Kartinkin, I think, should be punished according to chapter 1,452, sec. 4, and chapter 1,453; Euphemia Bochkova according to chapter 1,659, and Katherine Maslova according to chapter 1,454."

All these were the severest punishments that could be imposed for the crimes.

"The court will retire to consider their decision," said the justiciary, rising.

Everybody then rose, and, with a relieved and pleasant feeling of having fulfilled an important duty, walked around the court-room.

"What a shameful mess we have made of it," said Peter Gerasimovitch, approaching Nekhludoff, to whom the foreman was telling a story. "Why, we have sentenced her to hard labor."

"Is it possible?" exclaimed Nekhludoff, taking no notice at all this time of the unpleasant familiarity of the tutor.

"Why, of course," he said. "We have not inserted in the answer, 'Guilty, but without intent to cause death.' The secretary has just told me that the law cited by the prosecutor provides fifteen years' hard labor."

"But that was our verdict," said the foreman.

Peter Gerasimovitch began to argue that it was self-evident that as she did not steal the money she could not have intended to take the merchant's life.

"But I read the questions before we left the room," the foreman justified himself, "and no one objected."

"I was leaving the room at the time," said Peter Gerasimovitch. "But how did you come to miss it?"

"I did not think of it," answered Nekhludoff.

"You did not!"

"We can right it yet," said Nekhludoff.

"No, we cannot—it is all over now."

Nekhludoff looked at the prisoners. While their fate was being decided, they sat motionless behind the grating in front of the soldiers. Maslova was smiling.

Nekhludoff's soul was stirred by evil thoughts. When he thought that she would be freed and remain in the city, he was undecided how he should act toward her, and it was a difficult matter. But Siberia and penal servitude at once destroyed the possibility of their meeting again. The wounded bird would stop struggling in the game-bag, and would no longer remind him of its existence.