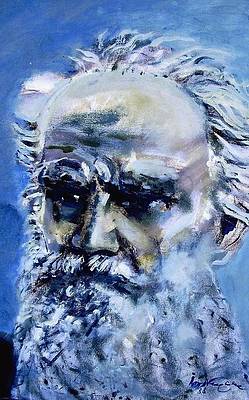

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1899

Source: Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy, translated from Russian to English by Constance Clara Garnett

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

As if to spite him, the case dragged out to a weary length. After the examination of the witnesses and the expert, and after all the unnecessary questions by the prosecutor and the attorneys, usually made with an important air, the justiciary told the jury to look at the exhibits, which consisted of an enormous ring with a diamond rosette, evidently made for the forefinger, and a glass tube containing the poison. These were sealed and labeled.

The jury were preparing to view these things, when the prosecutor rose again and demanded that before the exhibits were examined the medical report of the condition of the body be read.

The justiciary was hurrying the case, and though he knew that the reading of the report would only bring ennui and delay the dinner, and that the prosecutor demanded it only because he had the right to do so, he could not refuse the request and gave his consent. The secretary produced the report, and, lisping the letters l and r, began to read in a sad voice.

The external examination disclosed:

1. The height of Therapout Smelkoff was six feet five inches.

"But what a huge fellow," the merchant whispered in Nekhludoff's ear with solicitude.

2. From external appearances he seemed to be about forty years of age.

3. The body had a swollen appearance.

4. The color of the pall was green, streaked with dark spots.

5. The skin on the surface of the body rose in bubbles of various sizes, and in places hung in patches.

6. The hair was dark and thick, and fell off at a slight touch.

7. The eyes came out of their orbits, and the pupils were dull.

8. A frothy, serous fluid flowed continuously from the cavity of the mouth, the nostrils and ears. The mouth was half open.

9. The neck almost disappeared in the swelling of the face and breast, et cetera, et cetera.

Thus, over four pages and twenty-seven clauses, ran the description of the external appearance of the terrible, large, stout, swollen and decomposing body of the merchant who amused himself in the city. The loathing which Nekhludoff felt increased with the reading of the description. Katiousha's life, the sanies running from the nostrils, the eyes that came out of their sockets, and his conduct toward her—all seemed to him to belong to the same order, and he was surrounded and swallowed up by these things. When the reading was finally over, the justiciary sighed deeply and raised his head in the hope that it was all over, but the secretary immediately began to read the report on the internal condition of the body.

The justiciary again bent his head, and, leaning on his hand, closed his eyes. The merchant, who sat near Nekhludoff, barely kept awake, and from time to time swayed his body. The prisoners as well as the gendarmes behind them sat motionless.

The internal examination disclosed:

1. The skin covering of the skull easily detached, and no hemorrhage was noticeable. 2. The skull bones were of average thickness and uninjured. 3. On the hard membrane of the skull there were two small discolored spots of about the size of four centimeters, the membrane itself being of a dull gray color, et cetera, et cetera, to the end of thirteen more clauses.

Then came the names of the witnesses, the signature and deduction of the physician, from which it appeared that the changes found in the stomach, intestines and kidneys justified the conclusion "to a large degree probable" that the death of Smelkoff was due to poison taken into the stomach with a quantity of wine. That it was impossible to tell by the changes in the stomach and intestines the name of the poison; and that the poison came into the stomach mixed with wine could be inferred from the fact that Smelkoff's stomach contained a large quantity of wine.

"He must have drank like a fish," again whispered the awakened merchant.

The reading of this official report, which lasted about two hours, did not satisfy, however, the prosecutor. When it was over the justiciary turned to him, saying:

"I suppose it is superfluous to read the record of the examination of the intestines."

"I would ask that it be read," sternly said the prosecutor without looking at the justiciary, sidewise raising himself, and impressing by the tone of his voice that it was his right to demand it, that he would insist on it, and that a refusal would be ground for appeal.

The associate with the long beard and kind, drooping eyes, who was suffering from catarrh, feeling very weak, turned to the justiciary:

"What is the good of reading it? It will only drag the matter out. These new brooms only take a longer time to sweep, but do not sweep any cleaner."

The associate in the gold eye-glasses said nothing, and gloomily and determinedly looked in front of him, expecting nothing good either from his wife or from the world.

The report commenced thus: "February 15th, 188—. The undersigned, in pursuance of an order, No. 638, of the Medical Department," began the secretary with resolution, raising the pitch of his voice, as if to dispel the drowsiness that seized upon every one present, "and in the presence of the assistant medical director, examined the following intestines:

"1. The right lung and heart (contained in a five-pound glass vial).

"2. The contents of the stomach (contained in a five-pound glass vial).

"3. The stomach itself (contained in a five-pound glass vial).

"4. The kidneys, liver and spleen (contained in a two-and-a-half-pound glass vial).

"5. The entrails (contained in a five-pound earthen jar)."

As the reading of this report began the justiciary leaned over to one of his associates and whispered something, then to the other, and, receiving affirmative answers, interrupted the reading at this point.

"The Court finds the reading of the report superfluous," he said.

The secretary closed reading and gathered up his papers, while the prosecutor angrily began to make notes.

"The gentlemen of the jury may now view the exhibits," said the justiciary.

The foreman and some of the jury rose from their seats, and, holding their hands in awkward positions, approached the table and looked in turn on the ring, vials and jars. The merchant even tried the ring on his finger.

"What a finger he had," he said, returning to his seat. "It must have been the size of a large cucumber," he added, evidently amused by the giant figure of the merchant, as he imagined him.