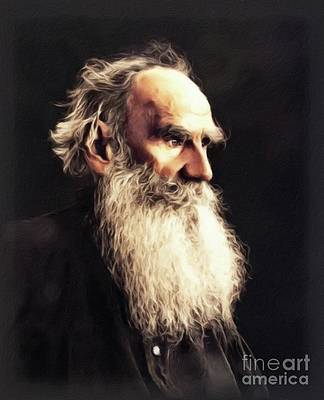

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1888

Source: Translated by Nathan Haskell Dole

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

At the time when I was about to leave the Caucasus, war was still in progress, and it was hazardous traveling by night without an escort.

I was anxious to start as early as possible in the morning, and therefore I did not go to bed at all.

A friend of mine came to keep me company, and we spent the whole evening and night sitting in front of my khata, or hut, on the street of the stanitsa, or Cossack outpost.

It was a misty, moonlight night, and so light that one could see to read, though the moon itself was invisible.

At midnight we suddenly heard a little pig squealing in a yard on the other side of the street. One of us cried :

"There 's a wolf throttling a young pig."

I ran into my khata, seized my loaded musket, and hastened out into the street. All were standing at the gates of the yard where the young pig was squealing, and they shouted to me, " Here ! here ! "

Milton came leaping after me, evidently thinking that as I had my gun I was going hunting; and Bulka pricked up his short ears and bounded from side to side, as if inquiring what it was that he should grip.

As I was running toward the wattled hedge, I saw a wild animal coming directly for me from the other side of the yard.

It was the wolf.

He was running toward the hedge, and gave a leap at it. I retreated before him and got my musket ready.

As soon as the wolf leaped down from the hedge on my side, I leveled the gun at him, almost touching him, and pulled the trigger; but the gun only gave a "chik" and missed fire.

The wolf did not stop, but darted down the street. Milton and Bulka set out in pursuit. Milton was near the wolf, but evidently did not dare to seize him ; while Bulka, though he put forth all the strength of his short legs, could not catch up with him.

We ran as fast as we could after the wolf, but wolf and dogs were now out of sight.

But we soon heard near the ditch at the corner of the stanitsa a barking and whining, and we could make out through the moonlit mist that something was kicking up a dust, and that the dogs had tackled the wolf.

When we reached the ditch, the wolf was gone, and both the dogs returned to us with tails erect and excited faces. Bulka growled and rubbed his head against me ; he evidently wanted to tell me about it, but was not able.

We examined the dogs and discovered that there was a small bite on Bulka's head. He had probably overtaken the wolf in front of the ditch, but had not dared to tackle him, and the wolf had snapped at him and made off. The wound was small, so that we had no apprehension in regard to it.

We returned to the khata, sat down, and talked over what had happened. I was vexed enough that my musket had missed fire, and I could not help thinking that, if it had gone off, the wolf would have fallen on the spot. My friend was surprised that a wolf had ven- tured to make its way into the yard.

An old Cossack declared that there was nothing wonderful about it ; that it was not a wolf, but a witch, and that she had cast a spell over my gun !

Thus we sat and talked.

Suddenly the dogs sprang up, and we saw in the middle of the street, right in front of us, the very same wolf ; but this time he made off so swiftly at the sound of our voices that the dogs could not overtake him.

The old Cossack after this was entirely convinced that it was no wolf, but a witch ; but it occurred to me whether it was not a mad wolf, because I had never heard or known of a wolf returning among men after once he had been chased.

At all events, I scattered gunpowder over Bulka's wound and set it on fire. The powder blazed up and cauterized the sore place.

I cauterized the wound with powder so as to consume the mad virus, in case it had not yet had time to reach the blood.

In case of the spittle being poisonous and reaching the blood, I knew that it would spread all over his body, and then there would be no means of curing him.