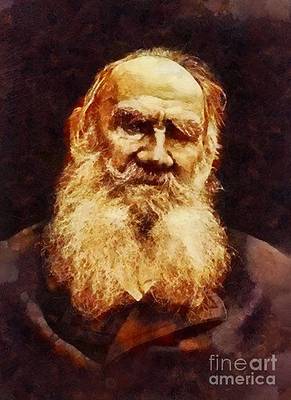

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1887

Source: "A Russian Proprietor and Other Stories," by Leo Tolstoy, translated by Nathan Haskell Dole, 1887, published by Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., New York, 13 Astor Place.

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

The next morning when Delesof was awakened to go to his office, he saw, with an unpleasant feeling of surprise, his old screen, his old servant, and his clock on the table.

"What did I expect to see if not the usual objects that surround me?" he asked himself.

Then he recollected the musician's black eyes and happy smile; the motive of the Melancholie and all the strange experiences of the night came back into his consciousness. It was never his way, however, to reconsider whether he had done wisely or foolishly in taking the musician home with him. After he had dressed, he carefully laid out his plans for the day: he took some paper, wrote out some necessary directions for the house, and hastily put on his cloak and galoshes.

As he went by the dining-room he glanced in at the door. Albert, with his face buried in the pillow and lying at full length in his dirty, tattered shirt, was buried in the profoundest slumber on the saffron sofa, where in absolute unconsciousness he had been laid the night before.

Delesof felt that something was not right: it disturbed him. "Please go for me to Boriuzovsky, and borrow his violin for a day or two," said he to his man; "and when he wakes up, bring him some coffee, and get him some clean linen and some old suit or other of mine. Fix him up as well as you can, please."[163]

When he returned home in the afternoon, Delesof, to his surprise, found that Albert was not there.

"Where is he?" he asked of his man.

"He went out immediately after dinner," replied the servant. "He took the violin, and went out, saying that he would be back again in an hour; but since that time we have not seen him."

"Ta, ta! how provoking!" said Delesof. "Why did you let him go, Zakhár?"

Zakhár was a Petersburg lackey, who had been in Delesof's service for eight years. Delesof, as a single young bachelor, could not help entrusting him with his plans; and he liked to get his judgment in regard to each of his undertakings.

"How should I have ventured to detain him?" replied Zakhár, playing with his watch-charms. "If you had intimated, Dmitri Ivánovitch, that you wished me to keep him here, I might have kept him at home. But you only spoke of his wardrobe."

"Ta! how vexatious! Well, what has he been doing while I was out?"

Zakhár smiled.

"Indeed, he's a real artist, as you may say, Dmitri Ivánovitch. As soon as he woke up he asked for some madeira: then he began to keep the cook and me pretty busy. Such an absurd.... However, he's a very interesting character. I brought him some tea, got some dinner ready for him; but he would not eat alone, so he asked me to sit down with him. But when he began to play on the fiddle, then I knew that you would not find many such artists at Izler's. One might well keep such a man. When he played 'Down the Little Mother Volga' for us, why, it was enough to make a man weep. It was too good for any thing![164] The people from all the floors came down into our entry to listen."

"Well, did you give him some clothes?" asked the bárin.

"Certainly I did: I gave him your dress-shirt, and I put on him an overcoat of mine. You want to help such a man as that, he's a fine fellow." Zakhár smiled. "He asked me what rank you were, and if you had had important acquaintances, and how many souls of peasantry you had."

"Very good: but now we must send and find him; and henceforth don't give him any thing to drink, otherwise you'll do him more harm than good."

"That is true," said Zakhár in assent. "He doesn't seem in very robust health: we used to have an overseer who, like him"....

Delesof, who had already long ago heard the story of the drunken overseer, did not give Zakhár time to finish, but bade him make every thing ready for the night, and then go out and bring the musician back.

He threw himself down on his bed, and put out the candle; but it was long before he fell asleep, for thinking about Albert.

"This may seem strange to some of my friends," said Delesof to himself, "but how seldom it is that I can do any thing for any one beside myself! and I ought to thank God for a chance when one presents itself. I will not send him away. I will do every thing, at least every thing that I can, to help him. Maybe he is not absolutely crazy, but only inclined to get drunk. It certainly will not cost me very much. Where one is, there is always enough to satisfy two. Let him live with me a while, and then we will find him a place, or get him up a concert; we'll help him off the[165] shoals, and then there will be time enough to see what will come of it." An agreeable sense of self-satisfaction came over him after making this resolution.

"Certainly I am not a bad man: I might say I am far from being a bad man," he thought. "I might go so far as to say that I am a good man, when I compare myself with others."

He was just dropping off to sleep when the sound of opening doors, and steps in the ante-room, roused him again. "Well, shall I treat him rather severely?" he asked himself; "I suppose that is best, and I ought to do it."

He rang.

"Well, did you find him?" he asked of Zakhár, who answered his call.

"He's a poor, wretched fellow, Dmitri Ivánovitch," said Zakhár, shaking his head significantly, and closing his eyes.

"What! is he drunk?"

"Very weak."

"Had he the violin with him?"

"I brought it: the lady gave it to me."

"All right. Now please don't bring him to me to-night: let him sleep it off; and to-morrow don't under any circumstances let him out of the house."

But before Zakhár had time to leave the room, Albert came in.[166]