From Socialist Review, 1981 : 1, 19 January–15 February 1981, pp. 9–10.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

|

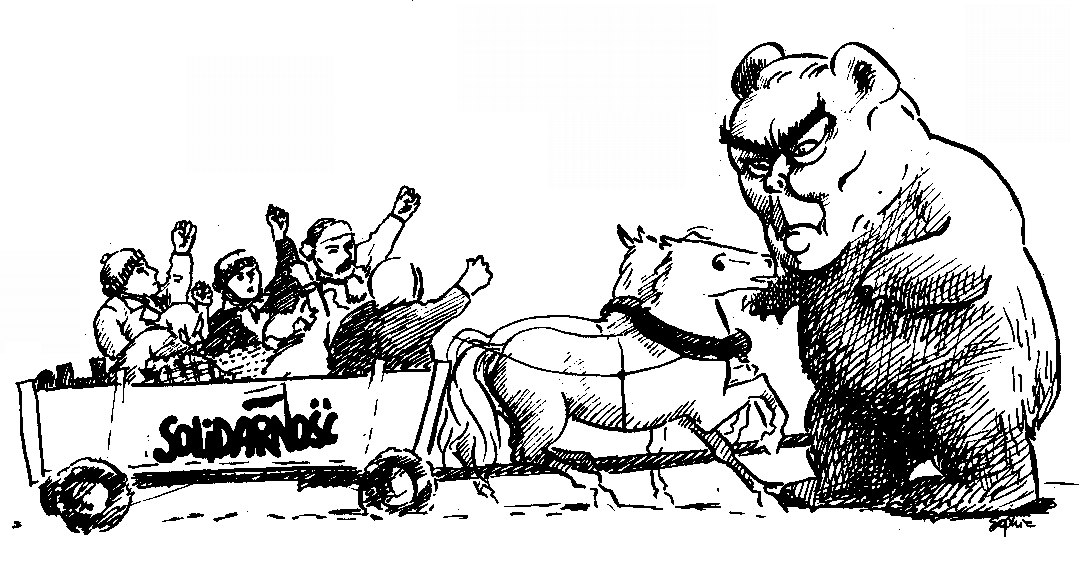

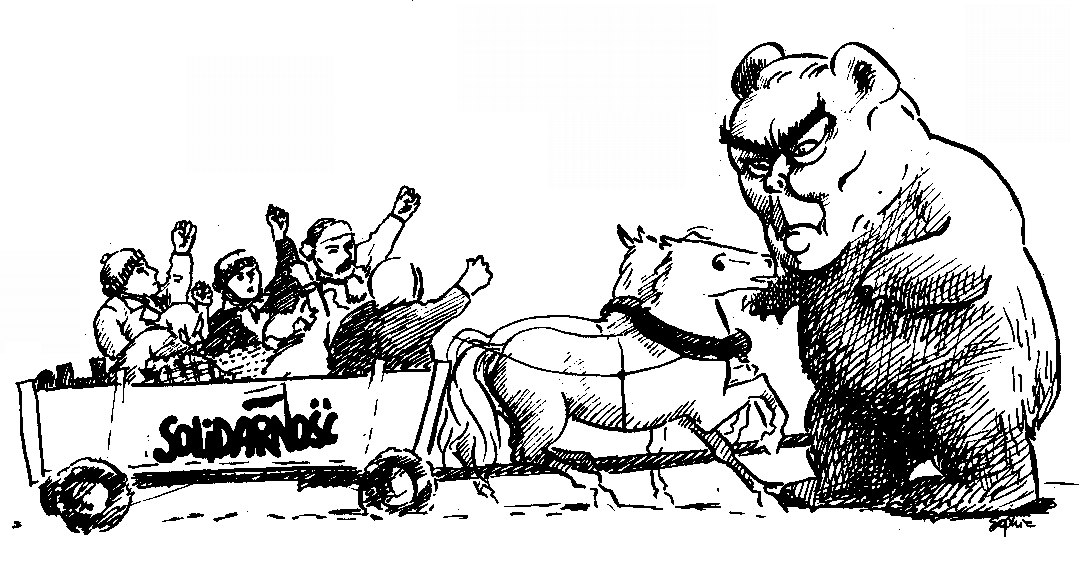

An absolutely solid response to the call to refuse to work Saturdays. The first use of police – fully equipped, with gas masks – to break workers’ occupations of public buildings. Threats of protest strikes in the South East of the country. Press attacks on the peasant branch of Solidarity. The ‘Christmas truce’ in Poland didn’t last long. What are the rulers of Poland – and Russia – going to do now?

Hardly was the Christmas break over than there were reports of new strikes in South-East Poland. Six months after the movement began last July, the power of the workers’ new organisations is still the biggest headache the rulers of Poland – or of Russia – can remember having.

The scale of the problem facing the Russians can be seen if you ask a simple question: Why have they not intervened militarily yet?

They went into Czechoslovakia in 1968 when faced with political and social unrest far less deep seated than that in Poland today. In Prague, it is true, the intellectuals and the students were questioning the one-party state and were beginning to influence many workers. But the ‘reform movement’ was still very much under the influence of Communist Party leaders who deplored ‘anarchy’ and pledged loyalty to Moscow. The official unions remained intact, even if some bureaucrats were being replaced. The intellectuals’ document 2000 Words that so infuriated the Kremlin did not actually organise strikes, it only suggested token work stoppages might be necessary.

The Polish movement is completely independent of all sections of the regime. The official unions have been displaced by new structures based, usually, upon regular meetings of delegates from the workplaces. Strikes take place all the time. The last attempt by the regime to limit the freedom of the Solidarity union – the attempt by the court to deny its legal registration until it changed its rules – ended with the regime having to use a higher court in order to cover a humiliating climb down.

Indeed, Kania is finding that the only way to avoid defeat when Solidarity pushes its demands is to pretend that his goals are the same as the union’s.

The result has been consternation in Moscow. The Russian, Czech and East German press again and again bemoan the ‘anti-socialist’ forces at work in Poland and especially in Solidarity – the same tone as before the entry into Prague in 1968. Indeed, only once before have the Russians faced a movement comparable to the Polish one today. That was in Hungary in October 1956.

Events are unfolding more slowly now than they did then. But the direction is the same. Seasoned bureaucrats are having to make so many concessions to give the appearance of being in control of things as to threaten all the structures by which they’ve got their way in the past. As the structures are weakened, so other groups like writers and journalists are beginning to assert their independence from the regime, thus making any eventual reassertion of bureaucratic power more difficult.

If the Russians have not invaded, it is not because they believe any claims from Kania that things are well under control. It is because they are frightened of intervening as yet.

They are frightened, in the first place, of the resistance the Polish workers may put up. Poland is a much larger country than Hungary or Czechoslovakia, and its people have a tradition of armed resistance to foreign domination. What is more, the country is strategically well placed to mount such resistance. The Russians do not want a repeat of Budapest 56 in a country with five times the population and a much larger and more sophisticated working class, straddled right across Moscow’s communication lines with its forces in East Germany and the supply lines for its high technology imports from West Germany. They remember that the Warsaw uprising of 1944 held out against Hitler’s empire for 63 days and they don’t want to face similar resistance.

They are aware, too, that the crisis throughout their bloc is much more serious than in 1968 and even than in 1956. Last year all the Eastern European countries experienced their lowest growth rates since the war, and in a few cases there were negative growth rates, real recessions. The various regimes have announced ‘plans’ for the next five years that involve at best stagnating real living standards, at worst cuts in real wages. People are grumbling not only in Warsaw, but in Budapest and Prague, Sofia and Moscow. The Russians recall only too well the strikes in their own huge auto factories at Togliattigrad, Gorki and Karma River last summer. There have been strikes and demonstrations since in Estonia and reports of discontent among tens of thousands of Czech miners close to the Polish border.

The Russians are in a dilemma. As news filters through to workers in the rest of the bloc of what Solidarity has won in Poland, the pressure is going to grow for similar organisations. But if the Russians move into Poland and do face massive resistance, the cost to themselves can be such as to provoke even more explosive disturbances behind their lines.

That is why at the time of writing they have not moved. Instead, they have allowed Kania a free hand to try a different strategy. It is one that relies on the threat of Russian invasion on the one hand, and on the other on co-opting the Catholic church and a section of the Solidarity leadership at the same time as scraping around in order to get enough resources together to alleviate the worst food shortages. The strategy is not a new one. It was, for instance, the one used by the former fascists who ran Spain to avoid a Portuguese-style explosion after Franco’s death. They offered a place in the political limelight to the leaders of the main organisations of the anti-fascist underground – the Communist Party, the Workers Commissions, the Socialist Party, the Basque and Catalan nationalist parties – in return for keeping the workers calm. And they ensured that rank-and-file workers were in a mood to accept the deal by pointing to the (exaggerated) danger of intervention by the extreme-right controlled army.

In Poland the Catholic church especially has shown itself willing to deal with the regime. In return for increased recognition for itself, it has begun preaching conciliation between the authorities and the mass movement. Early in December, as Moscow stepped up its pressure, the Polish bishops issued a statement condemning ‘actions which might expose the homeland to the danger of losing independence’. A church spokesman spelt out that the statement was aimed specifically at the leading dissident group, KOR, and the anti-Russian Confederation for an Independent Poland (Guardian, 13 December). Cardinal Wyszynski ‘appealed for restraint and social peace’. Prayers along these lines were said in every church in the country (Guardian, 15 December).

Shortly afterwards, a section of the Solidarity leadership repeated the same message. The best known leader, Lech Walesa told reporters, ‘Society wants order right now. We have to learn to negotiate rather than strike.’

So when the government arrested some Catholic nationalist oppositionists, Solidarity took no real action, although it formed a sub-committee in support of the prisoners. And when the courts deferred recognition of the Solidarity peasants’ union, the industrial leadership took no immediate national action – although workers in the South-East took token strike action.

Such calls for ‘social peace’ are very dangerous. Solidarity has gained its present strength because it has channelled behind it all the frustrations that have grown up under state capitalist rule – the resentments of millions of people at economic hardship, bureaucratic bullying, continual speed-up, petty corruption. If it tells those bearing such resentments to keep quiet, it is weakening its own base and preparing the ground for Kania or the Russians to move in to destroy the movement at a later stage. It is making the same mistake that the Dubcekites made in Prague immediately after the Russian invasion, of agreeing to oversee themselves the bureaucratic ‘normalisation’ that Brezhnev wanted.

Yet the chances of Kania’s strategy succeeding are not very great. In the case of Spain the transition to ‘democratic’ rule took place while the economy was still prospering, and the ‘sacrifices’ demanded of the workers was not very great. Perhaps more importantly, the social peace was enforced by a bureaucratised party, the Spanish Communist Party, with tens of thousands of dedicated, disciplined, followers and immense prestige after nearly 40 years of underground struggle. Solidarity is not (yet at least) that sort of bureaucratised, disciplined body. Its leaders were unknown workers six months ago and cannot cut themselves off from the rank and file that quickly, even if they want to. Although they bend one way under the pressure of the Russians, Kania and the church, they bend the other under the pressure of anger from below.

At the same time, the organisation of economic aid is not going as well as Kania would wish. The West Europeans want to help him out – both because they are afraid an upheaval in Poland would damage their growing trade with the Eastern bloc and because their bankers want to get back the money they’ve already lent. But the Russians are distrustful of any greater dependence of Poland on the West. They fear that this will begin to translate itself into political independence from themselves. They have been trying to exploit the crisis so as to push up Poland’s trade with the rest of Comecon (currently only two thirds of its trade with the West).

In such circumstances, it, is by no means certain even that Kania will get the food he needs to stop the queues in the streets of Warsaw turning nasty, with more strikes and, perhaps, riots.

The odds are that his overall strategy will fail. There will be more upheavals and confrontations. The regime will be faced again with the choice between diluting its own power and organising for repression. The Russians will get more and more jittery.

When this point is reached, the likelihood of Russian military intervention will be very great indeed. The costs will be high to the Russians, perhaps disastrously high. But that does not mean they will not intervene. It only indicates that the crisis in the Eastern bloc has reached a point where any option could open the door to revolutionary upheaval.

One final point. If the Russians do go in, the Americans are going to respond very differently to 1956 and 1968. They want an excuse to escalate the Cold War still further and to disrupt what they see as the potential danger of West Germany becoming too dependent upon Russia for its supplies of energy. And so, although they will not move militarily, they will mount a huge ideological barrage, portraying Russia as the greatest danger in the world.

It will be up to socialists to resist this barrage by joining opposition to Russian imperialism in Poland to opposition to US imperialism in Central America and elsewhere. We will need to polish up the old slogans: ‘Imperialism Out, East and West’, ‘Neither Washington Nor Moscow, But International Socialism’.

Last updated on 21 September 2019