From Socialist Review, No. 6, October 1978, pp. 3–6.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

What is happening in Iran? Here’s a 4-page analysis by Ali Ahmadi and Chris Harman

The Western press presents a very simple – and very distorted – view of the way the present wave of unrest in Iran has developed. They see its origins in an attempt by the Shah himself to introduce a few reforms, in the taking advantage of this by a few courageous liberal inclined intellectuals, and in an inexplicable growth of anti-regime religious feeling.

The real course of events is much different. After all, only two years ago the Shah, far from being ‘reform minded’ was trying to impose a single totalitarian party; the intellectuals, by and large, were completely silent.

And the religious opposition, like everyone else was cowed by the activities of the SAVAK. What broke the log jam was the action of the mass of city dwellers faced with the effects of the economic crisis.

In the summer of 1977 the Shah’s government tried to move more than a million people living in the shanty towns around Tehran. The reason, it seems, was to force them to move into the massively expensive housing schemes built by speculators inside the government.

Four months of disturbances followed as police attacked the shanty town dwellers, killing 40 of them and arresting many more.

The water and electricity supplies were cut off, as was garbage disposal. The response of the population was to find ways of providing these facilities for themselves, on a communal basis and in opposition to the regime.

The bitterness of the resistance his police faced forced the Shah finally to back down in the late summer and to cancel his decree on the shanty town.

The struggle in the shanty towns was accompanied by, and encouraged, a strike wave in the workplaces. In the spring and summer of 1977 more than 130 factories or depots were burnt to the ground – for example, the match factory at Tabriz, a paint-making factory in Karaj Road, Tehran, a seed-base oil factory of Khorasan, the General Motors assembly plant in Tehran.

In the same period there was a big strike of workers at the box making factory of Qazvim which led to the imposition of semi-martial law in the area.

The strikes expressed the determination of the workers to keep ahead of soaring cost of living – especially housing – costs, just as the Shah was introducing legislation to keep wage increases down to productivity increases.

The protests soon spread to another sector, who were given heart by the shanty town dwellers’ victory against an apparently impregnable regime.

The bank employees struck after the refusal of a salary increase. And then it was the turn of the so-called ‘national bourgeoisie’ – the intellectuals and the small bourgeoisie of the bazaars.

The intellectuals began their campaign of writing protest letters. The more courageous extended this to public poetry readings. Their agitation was joined by students throughout the country after a police attack on a poetry reading and on students at Tehran university.

Even the Financial Times admits that

‘during the past academic year the universities have been less a base for higher education than a battle ground where the Shah’s security forces, in riot gear and wielding wooden clubs, have almost daily squared off with embittered students frequently armed only with youthful enthusiasm and the occasional wooden chair’. (12 September 78).

The attacks on the students last autumn forced the religious leaders to increase their activity – especially as the small bourgeoisie of the bazaars was agitated by the increased competition of the monopolies and the attempts at price control.

The religious leaders began to join their voices to the major oppositional religious figure, Ayatollah Khomeini, who was exiled in 1963. There was a major clash in Qom between the religious led opposition and the Shah’s forces.

The Shah’s attempt to brutally smash the opposition merely led to it gaining increased sympathy and support.

For the first time since 1963 there was the closing of the bazaars throughout the country and the call to overthrow the Shah.

The centre of the opposition movement often became the Mosques, which offered a more or less legal focus for op-positional activity. The Shah’s attempts to close some of the Mosques forced more conservative religious figures to join the agitation.

The Shah was soon in a desperate panic. Forty days after the Qom clashes he had to repeat the same thing, and on a wider scale in the Northern city of Tabriz.

A brutal massacre there did not help things either. It created further unrest in other cities: Isfahan, Shiraz, Abadan, Tehran – in fact in all the major cities.

The regime then began a propaganda attack designed to split the opposition. It claimed that the religious opposition stood for a strict, puritanical Islam regime – although the religious leaders themselves had not demanded this – and tried to create panic with looting, attacks on women and religious minorities.

But the propaganda ploy failed. There was a complete one day strike in Tehran, with the Qom events repeating themselves, until the complete isolation of the regime was clear to all.

Meanwhile, as the Economic Intelligence Unit notes, ‘while the confrontations, in the streets were getting all the publicity, less advertised, but equally significant, the country has been beset by a rash of strikes directed above all at foreign companies.’

The depth and resilience of the opposition forced the Shah to backtrack for a time. He offered a number of concessions to the religious leader’s, sacking his prime ministers, first Hoveida and then Amouzegar, and replacing them with Sharif Emami, who is close to religious circles.

Emami set about establishing a ‘government of reconciliation’.

Almost overnight, 14 political parties and societies declared themselves. None sought to develop the organised power of workers, confining themselves to the demand for political liberty.

Allying themselves to the religious leaders who had up to then filled the political vacuum at the top of the mass movement they organised a series of mass rallies in Tehran and other centres.

The growing militancy of the movement had one welcome effect for the Shah. It gave a serious fright to various Western powers which had previously been pressing him to offer concessions and introduce a constitutional monarchy.

Continuing disorder presented the West with the choice between unconditional support for the Shah and chaos.

By 8 September the Shah felt strong enough to act. Early in the morning, martial law was proclaimed.

That same ‘Bloody Friday’, as it is now known, troops fired on demonstrators in Teheran. The authorities claimed that 97 people had been killed.

Opposition members of Parliament produced their own figures of thousands dead. One estimate is that between 7,000 and 9,000 people died on that single day in Tehran.

According to one source a secret mass grave has been dug in the army camp of Lashkark near Tehran.

A total news clamp down followed the shootings. However, the signs are that the struggle is far from over. Strikes are reported in Tehran, Tabriz and other centres.

One opposition MP described how he could hear machine-gun fire in the streets as he composed his speech opposing the imposition of martial law.

Unrest is reported within the army. One soldier is said to have refused to fire on the demonstrators on 8 September instead killing his commanding officer and then himself.

Support has come to the Shah from all sides: a phone call from Carter, a letter from Callaghan, a promise of ‘non-interference’ from the Russians, visits from Chairman Hua Kuo-Feng and the Japanese prime minister Fukuda. Oil, apparently, is thicker than blood.

|

The present huge wave of struggles bears remarkable similarities with previous movements against the monarchy. In each case a fantastically important role in developing the struggle has been played by the working class. But except in the years immediately after the Russian revolution of 1917 the workers have not had a revolutionary leadership capable of safeguarding their independent role in struggles they initiate. In 1941-53 and in 1958-63 the workers shook the self-confidence of the monarchy. But then the ‘national bourgeoisie’ moved into action and soon exercised hegemony over the struggle. The same thing is happening now with the same representatives of the small, so-called national, bourgeoisie playing a role – the Mosques, the intellectuals, and to some extent the National Front. But the ‘national bourgeoisie’ does not have a programme, either for the country or for the movement. Its most radical elements on occasions shout ‘Death to the Shah’, and make anti-imperialist speeches, but make no suggestion at all as to what social change should be made. They cannot, because they are no longer fighting the feudal monarchy of seventy or even thirty years ago, but a state monopoly capitalist monarchy. They are being driven down by the development of capitalism, but as representatives of a stratum that has traditionally opposed the Shah with the demand for the devlopment of capitalism in Iran, they do not know how to respond to this. Hence, despite considerable individual courage, they cannot be expected to offer any clear leadership to the movement at decisive moments of confrontation. The industrial workers could. They have a very long history of struggle behind them. But they do not have any sort of party capable of assimilating the lessons of that struggle. The remnants of the old Tudeh (Stalinist) Party can be expected to compromise with the ‘national bourgeoisie’ just as it is tempted to compromise with elements in the Shah’s camp. And those who have broken from that path to the left have also, unfortunately, tended to abandon the mass struggles of the workers for the delights of small group guerillarism. Instead of being with the class and its mass struggle, clarifying the issues at stake, they have been standing on the by-lines, waiting for the mass struggle to subside so that their individual heroism can come to the fore again. So as in 1953 and 1963, the Shah could survive – not because of his strength, but because of the confusion of his enemies. |

Iran has known two great periods of revolutionary turmoil in the present century. In both the two components of the present opposition movement, the so-called ‘national bourgeoisie’ and the working class played key roles.

The years 1906 1911 were marked by very bitter struggles between the constitutional movement and the Iranian monarchy and its feudal backers.

The monarchy and the large feudal landlords were proving themselves incapable either of developing the counter of protecting it from near absorption into the colonial empires of Britain and Russia.

The merchants, small traders and small manufacturers of the towns became increasingly oppositional.

Because of their close ties with the local mosques these (as at later dates) quickly became the focus for much of their ‘constitutional’ anti-feudal sentiment.

But some of the incentive for the ‘constitutional’ movement came from a different source – Iranian emigrants who had obtained work in Southern Russia and who had become involved in the revolutionary movements in Russia in 1905

In the aftermath of the First World War and the Russian revolution the monarchy nd the feudalists came close to defeat in bitter fighting with the bourgeois and revolutionary Communist opposition movements.

But in 1921 the British embassy arranged a coup by which an upstart Cossack officer Reza Khan – the father of the present Shah – took power, unified the country with British help, and proclaimed a new dynasty. With the support both of the feudal landowners and a section of the so called national bourgeoisie he was able to smash the flourishing working class movement and drive its leaders into exile.

Reza Khan made the fatal mistake at the beginning of the second world war of supporting the Germans.

The British, who had brought him to power twenty years before, now removed him from power with Russian help. For six years the country was divided into Russian and British spheres of influence and it was very difficult for the new monarch, the present Shah, to prevent a new flourishing of the opposition.

Movements for national independence seized power in areas inhabited by the Azar and Kurdish minorities, while huge strikes broke out among the workers, especially the oil workers.

The government was able to smash these movements – partly because of British support, partly because the most influential force within the working class movement the pro-Russian Tudeh Party refused to develop them in a revolutionary direction (even at that stage it argued for ‘gradualism’ not revolution).

However, although they smashed these movements, the feudalists, the Shah and the British were not strong enough to prevent a new growth of the ‘constitutional’ national bourgeois opposition, now organised in the National Front of Mossadeq.

There was a new wave of strikes in the oil fields in 1951 and then mass demonstrations in Tehran. The Shah was forced to appoint Mossadeq prime minister and finally, early in 1952 to give him real power to nationalise the oil fields.

Mossadeq was kept in power by the mass movement. But the effects of the movement were already frightening important sections of the ‘national bourgeoisie’: there were 200 strikes in Mossadeq’s first year in office.

Mossadeq responded by implementing a law banning certain strikes and giving he police powers to attack workers. When the Shah fled into exile fear of the news prevented Mossadeq proclaiming a republic.

On 11 May 1953 the Shah took advantage of this vacillation to hit back. Gangs of lumpen proletarian thugs invaded the centre of Tehran, and while the ‘national bourgoeis’ and Tudeh Party leaders assured people everything was alright, the Shah carried through a coup.

The coup was very much organised by the CIA, who soon afterwards together with the Israelis helped the Shah set up a new secret police, the SAVAK.

In return for aiding the coup, the US was able to begin to displace Britain as the main imperialist power in Iran: the denationalised oil fields were now run by a consortium of American and British oil companies instead of exclusively by Anglo-Iranian (now renamed BP).

The compromise between British and American imperialism was matched by another compromise: between the old feudal landlords and a section of the bourgeoisie.

The state began a process of industrial development in collaboration with certain (predominantly American) foreign corporations. This provided a monopoly market for favoured sections of the local bourgeoisie and an opportunity for the old feudal landowners to move their wealth from land to industry.

A land reform programme which involved them selling some of their land to better off peasants provided them with the cash they needed for industrial investment.

This was the ‘White Revolution’, of which the Shah’s admirers boast. In effect, it was the state aided transformation of the old feudal ruling class into a new monopoly capitalist ruling class linked to foreign interests.

Excluded from the benefits of the ‘white revolution’ were:

It is the revolt of these excluded sections which lies behind the present events.

Three or four years ago it was fashionable to talk of Iran as ‘the superpower of the future’. The Shah had set out to make the country into the fifth economic power in the world and to lead it ‘into the Great Civilisation’.

|

Sycophants throughout the world believed in his ability to do so. After all, Iran had oil, and the price of oil had just quadrupled.

Today even the sycophants are much more guarded in their claims.

‘Iran will be hard put’, says a new report for businessmen, Operating in Iran, ‘to attain its oft-proclaimed goal of becoming the world’s fifth economic power with a GNP of $190bn by the mid 1980s.’

Last year the real rate of economic growth slumped to 2.8 per cent. This compares with a claimed growth rate in 1974-5 of 41.6 per cent.

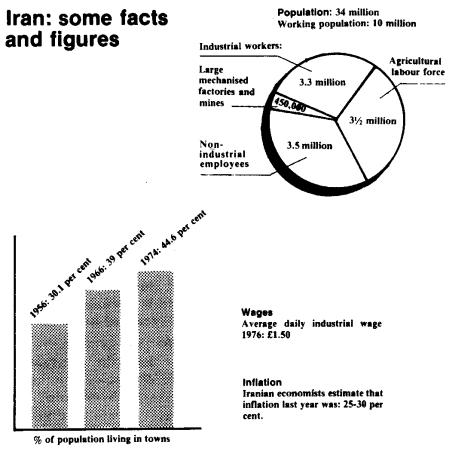

At the same time the rate of inflation has arisen to about 25-30 per cent. What’s gone wrong?

The grandiose schemes drawn up for industrialisation after the 1973 oil price rise were based on the assumption that all that was needed was to pour money into the economy and economic expansion was guaranteed.

But the pre-existing industrial base was just not big enough to feed this expansion. It soon ran into problems like those that have beset similar grandiose expansion plans in the state capitalist countries of Eastern Europe.

The raw materials and the components to keep the expansion going did not exist within Iran. They had to be imported from abroad, through congested ports and with inadequate transport facilities.

All sorts of bottle-necks arose which held up particular investments for months at a time. For instance, last year it was estimated that something like 20 per cent of industrial output was lost because of power failures (shortage of electricity).

Despite a continual flow of labour to the cities from the countryside, there was an acute labour shortage: it is estimated that there are 400,000 vacancies for skilled labour alone, despite an estimated 120,000 ‘illegal’ immigrants – mostly from Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

The problem of shortages has been made worse by a continual run down in the agricultural sector. The ‘White Revolution’ bought off the old feudalists by offering them a lucrative future in the monopolistic sector of industry.

But by the same token it removed any incentive for investment to take place in agricultural rather than industry. The most active part of the rural population has been lured to the cities by the industrial expansion, agricultural out put has slumped.

Twenty years ago Iran exported agricultural produce. Now it imports a growing amount, which is expected to eventually to half the total.

While all these problems have been accumulating, the price of oil internationally has stagnated. Iran is having to fork out huge sums for raw materials, for industrial components, for foodstuffs – and for the Shah’s massive arms bill.

Oil revenue is not rising to meet these needs. The dream of 1973-4 has turned into an economic crisis. And the crisis will get worse as time goes on: it is estimated that Iran’s oil revenue will halve in the next 15 years.

The Shah would like to get out of this crisis by exporting manufactured goods.

But here it is doubtful if Iranian industry can really compete with established foreign giants. As Operating in Iran notes, ‘Most foreign observers question the viability of developing heavy industry oriented towards exports.’

So do Iran’s own monopoly capitalists. They have preferred to put their money into speculation or, at best, producing consumer goods for the national protected market where the only competition is from the small manufacturers and traders of the bazaars.

‘Officially total investment increased 27 per cent in 1976-7 and added value of industrial production registered a real 17 per cent growth ...

‘This growth is concentrated in the petrochemical and steel sectors, thanks to public sector investment, and in the booming housing and construction sector where easy big returns are common, while private sector manufacturing industrialists have tended to complete existing investment and to be wary of launching new projects ... The reason boils down to narrow profit margins.’

The flow of funds into speculation has led to the huge increase in land and housing prices in the city, which has cut into the living standards of workers and the lower middle classes, further feeding the pressures for inflation.

Last year half the increase in the cost of living was caused by housing costs alone.

The Shah’s response has been to put the burden for slowing down inflation on those hardest hit by it. He has introduced price controls which it is easy for the monopolies and foreign companies to evade, but which hit very hard the mass of small traders and manufacturers.

This has been one of the most direct causes of the ‘Bazaar’ and religious protest movements. And he has encouraged big industrialists to resist wage demands – one of the causes of the growing working-class agitation.

‘The situation in Iran reminds one of the last days of Tzarist Russia’. That was the London Evening Standard – back in August 1962.

A new wave of struggle had begun within six years of the coup that overthrew Mossadeq, in 1958-9. Striking taxi drivers in Tehran fought with the police outside the parliament building, Isfahan’s workers struck against an inadequate bread ration, workers in Bandar Shahpur struck for higher wages.

Their example was followed in 1959 by Esfahan textile workers, by Tehran printing workers, by 30,000 building workers in Tehran.

The King of Kings did not trust his subordinates to deal with this strike. He personally took charge of police and SAVAK who were in action within half an hour of the strike starting.

He ordered the police and army to machine gun the workers, killing 50 and filling all of Tehran’s hospitals for the poor with the wounded.

But the success of the great general the Shah against the bricklayers was not complete: he was forced to concede some of their demands.

The wave of strikes continued through into 1960 and 1961 despite repeated attacks by the police and the workers example began to be followed by other groups.

The students were now in action, and there were a growing coordination of strikes and of activity between workers and students.

It was possible for a Tehran weekly paper to note that one Isfahan textile factory had been on strike 52 times between 1957 and 1961. And this was nothing compared to the tempo the strike wave reached in mid 1962.

The workers’ movement drew into the struggle the other classes – including the ‘national’ bourgeoisie (or rather, petty bourgeoisie) that had lost power in 1953.

In May–June 1963 scenes very much like those of the last few weeks took place, with traders from the bazaars going on to the streets with the mass of the population under the leadership of outspoken religious figures from the Mosques.

Yet there was no coherent political programme or leadership to the movement, and the Shah was able to play a last card to save himself. He ordered his police and army to begin shooting straight into a huge demonstration.

He was heard saying over the army radio, ‘Do not shoot over their heads, shoot to kill, shoot to kill. Don’t try to maim their legs, shoot to kill’.

The number killed on the first day was between 10,000 and 15,000. Yet it took three days of bitter fighting for the army and police to gain control of the whole capital.

The Shah was victorious however, not because of his ruthlessness, but because there was no organisation or clarity on the part of his opponents as to what they were trying to achieve.

The spontaneous workers’ movement was phenomenally courageous. But it did not have a working-class party capable of providing it with direction.

And the ‘national bourgeoisie’ could not even raise a simple slogan, as it had been able to raise the slogan of nationalisation of the oil fields ten years before.

Last updated on 13 September 2019