(Source: R. A. Gordon: Business Fluctuations, New York 1961, p. 272)

From International Socialism 2:1, July 1978, pp. 79ff.

Transcribed by Christian Hogsbjerg.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

We are four and a half years into the worst world crisis since World War II and there seems to be no end to it in sight.

An understanding of this crisis is central to the strategy and tactics of revolutionary socialism. Are we faced with a temporary hiccough in the upward curve of capitalism? Or are we in for decades of decline for the world system?

Ernest Mandel claims this book provides some of the answers. He offers, he claims,

‘A Marxist explanation of the causes of the long post war wave of rapid growth in the international capitalist economy ... and at the same time to establish the inherent limitations of this period which ensured that it would be followed by another long wave of increasing social and economic crisis.’

Belief that Mandel has accomplished this task has led at least one of his acolytes to suggest, in the blurb to the Penguin edition of Marx’s Capital that ‘Late Capitalism is the only comprehensive attempt to develop the theoretical legacy of Capital.’

The book is certainly comprehensive – it deals in nearly 600 pages with the growing internationalisation of production, the relations between advanced and ‘backward’ countries, the increasing role of the state, the role of arms in the economy, the increased rate of technical innovation, the problems for markets and the rate of profit – to name but a few of the characteristics of ‘late capitalism’.

And yet it fails to come to terms with the central problems we face – to grasp the dynamic interaction of these different features, in a way that enables us to see why the crisis is like it is, why the system is cracking more at certain points (Poland, Egypt, Ethiopia, South Africa, Italy, perhaps Britain) than at others (West Germany, US).

The failure expresses itself in a failure to take a clear, unequivocal stand on controversial questions that divide Marxists from would-be Marxists. Mandel wants to accept the theory of ‘unequal exchange’ and to reject its most prominent proponents; he wants to use chunks of the permanent arms economy, but reject its theoretical underpinning; he wants to reject Rosa Luxemburg’s reproduction schema (proving that capitalism must break down through its inability to provide itself with markets) at one point only to bring them into play again through the back door at a later point; he wants to talk about the enhanced role of the state, but to ignore the extent to which it has shifted the anarchy of the system to the international level; he wants to say that imperialism has changed since Lenin’s time but also insist that it hasn’t; he wants to point out the bureaucratic inadequacies of the East European economies, but also to pay homage to the myth of a ‘higher economic system’ than capitalism. In short, he always wants to have his theoretical cake and eat it.

Lack of precision in Marxist politics leads to vacillation between the classes at crucial moments of struggle, what is usually called centrism. Lack of precision in Marxist theory leads to confusion as to what the practical tasks of the moment are. Mandel’s book encourages precisely this confusion.

In the last few years a whole array of would-be Marxists have emerged who tailor their alleged theoretical insights to the fashions in political practice – the theorists of ‘Third Worldism’, of ‘The new working class’, of ‘neo-capitalism’, of ‘socialism with a human face’, or ‘internal colonialism’. Mandel always seems to end up in a pose of loving up to these would be theorists (and some of their practical conclusions), but ‘critically’.

Mandel’s very method of work is misplaced.

He aims to show how modern capitalism can be fitted into the categories deployed by Marx in Capital.

‘To demonstrate that the “abstract” laws of motion of ... capitalism discovered by Marx in Capital ... remain operative and verifiable in and through the unfolding “concrete” history of contemporary capitalism.’

According to Mandel, capitalist crises are the result of the coming together of the various different factors pointed to by Marx. Analysis, according to him, consists in merely identifying these factors, and then having a chapter or two in which their various expressions are piled one on top of the other.

But Marx’s own approach was in reality very different. It was to identify the individual elements of the system through analysis, and then to show how they interacted dynamically, changing one another in the process. That is why he insisted his method was dialectical, concerned with interaction and mutual transformation.

Once you miss these interconnections, you miss the dynamic of the system; you can see the system in the manner of the bourgeois economist as made up of the different components of a smooth running machine, even a machine that is subject to accidental breakdowns (in Mandelese ‘conjunctural’ crises). But you cannot grasp the intrinsic contradictions of the system, contradictions based upon the way in which the total system accumulates, with accumulation producing an aging of the system, and the aging destroying the mainspring of the system’s own dynamic.

For Marx, the categories he developed were significant because they enabled you to see the system as a self-contradicting totality, which is in a permanent process of transformation – a transformation that must affect the very categories of analysis themselves.

For Mandel, the categories are a list to be measured up against the system, to prove that ‘Marxism’ is still valid. The method is the opposite of Marx’s own – and, for that matter, of those who really developed Marxism after Marx. Thinkers like Lenin or Bukharin or Luxemburg were often wrong. But they did use theory to illuminate the development of the system. They could do so because they were prepared to modify Marx’s categories in the process of applying them. They never indulged themselves in pedantically listing categories off one by one against the system.

The man who did do such listing was the ‘Pope of Marxism’, Karl Kautsky. But Kautsky’s obsession with the letter of Marxism made him lose its spirit. He was unable to refute the shallow criticisms of the revisionists because the method of ‘listing’ does not explain how the dynamic of capitalism has produced new features. The revisionists could point to the novelty and claim it contradicted Marxism. The ‘Pope of Marxism’ could only point to the letter of Marxism and claim that it contradicted the novelty.

The fashionable Marxists of today are very like the revisionists of Kautsky’s time (except that to protect their left flank they usually claim that their ‘improvement’ of Marxism is a version of the real thing). Mandel has not the method to refute them. Yet he cannot deny the existence of some of the superficial phenomena to which they point. And so he ends up half agreeing and half disagreeing with them. It is this that leads to repeated self contradictions, to an underhand revision of Marxism – as when in order to make concessions to the ‘unequal-exchangists’ Mandel talks of value based upon ‘labour’ rather than socially necessary labour time (pp. 345 & 351) – to absurd claims, and to random predictions.

In the space of a relatively short review, I cannot point to-all these examples here. I will instead concentrate on a couple of sections – the sections where Mandel tries to analyse the post-war boom and its breakdown and where he criticises the analysis of this put forward by this journal over the years.

Mandel’s attempt to explain the long boom of the 1950s and 1960s begins by referring back to a Russian (Menshevik) economist of the 1920s, Kondratieff.

Kondratieff argued that just as there were short term boom-slump cycles, there were also long-term cycles of several decades. For a number of decades the system would show an upward movement, with relatively long and high booms and relatively short and shallow slumps. Then a turning point would be reached, followed by shallower booms and more intense slumps. But eventually another turning point would be reached, and the system would start moving upwards again.

Kondratieff was a Menshevik precisely because he saw the ups and downs as ‘major cycles’ – a cycle is something that by definition repeats itself, with the down-turn giving rise to the upturn, giving rise to the down turn etc. For the system, Kondratieff’s notion of ‘cycles’ was very optimistic: however bad things were, they would eventually get better! That was why Trostsky denounced Kondratieff, even though he himself at the Third Congress of the Communist International had insisted on distinguishing between periods when the ‘curve of capitalist development’ was upward and when it was downward.

‘It is already possible,’ Trotsky wrote, ‘to refute in advance Professor Kondratieff’s attempt to invest epochs labelled by him ‘major cycles’ with the selfsame rigid lawful rhythm that is observable in minor (i.e. slump-boom – CH) cycles. The character and duration (of large sections of the capitalist curve of development) is determined not by the cyclical interplay of capitalist forces, but by those external conditions through whose channel capitalist development flows.’ (L. Trotsky The Curve of Capitalist Development, translated in Fourth International, May 1941).

Mandel, in a style that is typical of his intellectual slipshodness, quotes Trotsky on Kondratieff – and then goes on to pretend that the difference between the two does not matter. Perhaps that is because he covertly lines up with Kondratieff against Trotsky: he sets out to discover the ‘cyclical interplay of capitalist forces’ that produce what he calls long term ‘waves’. A wave, like a ‘cycle’ is something that moves up and down with a mechanical regularity.

The mechanism internal to capitalism that produces long waves works, according to Mandel, like this:

(1) For a period capitalism develops as Marx predicted it would in Capital. There is a growing tendency towards slower growth and greater slumps. During this period, the falling rate of profit deters capitalists from completely reorganising production so as to utilise advances that have taken place in science and technology.

“Under normal conditions of capitalist production the value set free at the end of one 7- or 10-year cycle are certainly sufficient for the acquisition of more and more expensive machines than were in sue at the beginning of the cycle. But they do not suffice for the acquisition of a fundamentally renewed productive technology, particularly in Department I (production of the means of production – CH), where such renewal is generally linked to the creation of completely new productive installations.” (p. 111)

So potential innovations accumulate unused; there is growing unemployment; the crisis of the system means that a growing proportion of capital cannot find a profitable outlet for investment and remains idle.

(2) But, Mandel goes on to argue, after four or five cycles like this there is the potential for a new wave of investment, using up all the ‘excess capital’ and all the unemployed labour, because

“The values set free from the purchase of additional fixed capital in several successive cycles enables the accumulation process to make a qualitative leap forward ... The cyclical recurrence of periods of underinvestment fulfils the objective function of setting free the necessary capital for this kind of technological revolution.”

When that point is reached all the stored-up innovations can be brought into effect at once; the whole capital of society is reorganised; doing this provides work for the unemployed capital resources.

(3) But the new surge of investment will not occur of its own accord. It first requires a countering of the long term tendency of the rate of profit to fall. According to Mandel the necessary rise in the rate of profit will take place if there is a ‘sudden fall in the organic composition of capital’, a ‘sudden increase in the rate of surplus value’ through for instance, ‘a radical defeat and atomisation of the working class’; a ‘sudden fall in the price elements of constant capital, especially of raw materials’; ‘a sudden abbreviation of the turnover time of circulating capital’ through improved transport and communication.

If all, or most of these things take place, then it will suddenly be profitable to invest as it did not used to be. The system will move from a phase of stagnation and decline to one of expansion.

It only needs to be added that the increase in the rate of exploitation of the workers that is needed for this is prepared by the long periods of capitalist decline. A low level of investment leads to an increasing reserve army of unemployed labour. This begins to create the pressure for reduced wages and increased exploitation, although this pressure may only become fully effective when the political and social obstacles to reduced wages and speed-up have been eliminated with a massive defeat for the working class movement.

Mandel claims this combination of factors turned the great slump of the inter-war years into a new period of long term expansion.

“Two decisive factors in our view explains the long wave with an undertone of expansion which lasted from 1940 (45) to 1966. In the first place the historical defeats of the working class enabled fascism and war to raise the rate of surplus value. In the second place the resultant increase in the accumulation of capital (investment activity), together with an accelerated rhythm of technological innovation, and a reduced turnover time of fixed capital led in the third technological revolution to a long-term expansion of the market for the extended reproduction of capital on an international scale, despite its geographic limitations.” (p. 442)

For a short time, then, the increased rate of innovation leads to a mitigation of short term cyclical crises and to a rapid rate of growth for the system.

(4) But eventually, the ‘wave’ of innovations begins to falter. At the same time, full employment leads to workers gaining new confidence. The classic pressure on profit rates begins to be felt. The well spring of expansion begins to dry up, and a new period of crises and stagnation begins.

There is a certain beauty in Mandel’s model of the long term ‘waves’. If you are a capitalist or a reformist you can look at it and feel assured that there is light at the end of the tunnel. Damn it all, things may be uncomfortable, but the ‘hidden hand’ is still there to bring things right. In the long term at least, Keynes may be dead but demand and supply, resources and expectations, production arid consumption, profit rates and productive potential, will accord with one another again.

But the beauty is the beauty of a machine that will never move. For the cogs of the different parts of the argument just do not fit together.

The objections to Mandel’s account of the ‘long waves’ are both factual and theoretical. [1]

First, the factual criticisms. These centre around the claim that there was an ‘upturn’ after 1945 because of ‘historic defeats’ for the working class and an increased rate of exploitation; followed by a downturn in the late 1960s because of a decline in the reserve army of labour, increased working class strength and a decline in the rate of exploitation.

The western economy in 1945 was dominated by one major economy, the US and one lesser one, Britain. The other European economies were in a state of devastation. Yet where was the ‘historic defeat’ in the US and Britain? The previous 10 years had seen a growth of the strength of the working class organisations in both countries, in the US a vast growth with the development of the CIO (which Mandel hardly bothers to mention). There had been a more or less voluntary surrender of some of their power by the unions during the war. But this was not at all the same as a ‘historic defeat’. So why should the ‘long upward wave’ have begun then?

Again, where there had been defeats, in Germany, in Italy, in Japan, even in Britain in 1926, these had been many years before. So if defeats followed by a sudden shift in the balance of class forces cause the shift from a downward wave to an upward one, why hadn’t that taken place 10 or 15 years before? Certainly, as Mandel himself pointed out, the technological innovations exploited after 1945 existed 10 years before.

Furthermore, none of Mandel’s figures purporting to show a shift in the rate of exploitation to the advantage of capital justify the claim that they made rapid capital accumulation possible in the 1950s but not in say the early 1930s, After all Mandel himself shows the share of labour in the German national income as only 2.8 per cent less before the prolonged boom of the 1950s than before the prolonged slump of the 1930s.

Similar objections can be made to the claims that it was increased working class pressure that upset the capitalist apple cart in the late 1960s.

Mandel claims that the system entered a period of renewed crisis when ‘the very dynamic of the expansionary long wave started to reach the limits of the reserve army of labour ... and a pronounced increase in real wages started to roll back the rate of surplus value.’

This part of Mandel’s argument is very similar to that put by a number of right wing economists, by two would-be Marxists (Glyn and Sutcliffe) and by a whole number of revisionist economists (Rowthorne and Purdy, for example). [2]

The same objections have to be made to the argument in each case. Firstly the tendency for the rate of profit to fall has been displayed in all capitalist and state-capitalist countries. [3]

This has been regardless of the strength or otherwise of the working class movement – so for example, it has been possible for a number of commentators to point to lower profits in key West German industries than in Britain, despite the stronger organisation of the working class in Britain and lower productivity.

It has also been regardless of the relative size of the reserve army of labour. Profit rates have, for example, been falling in the United States for nine years despite the tendency for the level of unemployment to move upwards, so that it is as high now in booms as it used to be in slumps.

Mandel’s own figures show that in the period 1951–1969 when unemployment was considerably smaller than it is now, the level of profitability never moved more than about 1.1 per cent above or below an average figure of 13.2 percent.

|

1951 |

1956–60 |

1961–65 |

1966–70 |

|

14.3% |

12.2% |

14.1% |

12.9% |

It was only in the early 1970s that they fell dramatically to 9.8 per cent.

Yet the early 1970s were a period of higher unemployment than in the 1950s and 1960s and a period of stagnating, or even falling real wages in the US.

What has been true of the biggest capitalist economy has also been true in at least some other important cases. Unemployment in Britain has been much higher in the 1970s than say in the 1950s. The rate of growth of real wages has been less – indeed in the last three or four years real wages have tended to fall. Yet the rate of profit has plummeted, while it remained more or less stable from 1955-1965.

Even in West Germany, the crisis of profitability and reduced investment has occurred at precisely the time when the ‘reserve army of labour’ has grown to a figure of about 1 million (plus 1 million repatriated immigrant workers) – and persists despite the low level of working class struggle for a number of years.

From the empirical evidence it does not seem that it has been an increase in the power and combativeness of workers that has caused the crisis. Rather, it is because the system has entered a new period of crisis that it cannot maintain its profitability, even where workers accept lower wage increases than they used to (or even a fall in their real wages).

By starting with the size of the reserve army of labour, the level of wages and the rate of exploitation as the cause of the crisis, Mandel, Glyn & Sutcliffe, Purdy and the rest put the cart before the horse. They fail to see that the cause of the crisis must lie outside the simple struggle between workers and capitalists over the distribution of the national cake. It is the crisis that determines the conditions of that struggle, not vice-versa.

Mandel’s failure to see this plants an element of extreme arbitrariness bang in the middle of his analysis. After all, if a fall in the reserve army of labour alters the balance of class forces in the interests of workers and leads the system, after a time into prolonged crisis, can’t we expect that the growth of the reserve army over the last few years will alter the balance back once more in the capitalists’ favour and lead the system out of the crisis? This is what Mandel claimed happened in the 1940s. Why can’t it happen again now – as revisionists and reformists of all hues pretend?

Mandel can only escape such a conclusion by reaching desperately for other explanations of the crisis to prop up his more than rickety structure.

At points the propping up comes from the idea that there are ‘waves’ of innovations – as if there is some magical device in operation that means that after the lapse of a certain number of years human ingenuity must begin to dry up and technological progress grind to a halt. Once again the cart is put before the horse. If the system were confident of endless expansion, then it would provide the input of resources to ensure an endless output of new techniques to be applied in production. It is not some autonomous realm of ‘innovation’ that produces long boom or long crisis. It is long boom or long crisis that determines the incentives for technological innovation.

Mandel cannot be too sure of this explanation, because he turns to others. Out of the blue we are presented with “reproduction schema’ very much like those drawn up by Rosa Luxembourg in 1912. These purport to show that the system will inevitably break down. Maybe it will. But that is not a conclusion you can draw from the equations alone. For why then should the breakdown occur now rather than a hundred or seventy or twenty years ago?

The equations were true in Marx’s time yet there have been long periods of expansion of the system since then. The fact is that the equations by themselves prove nothing. What matters are the values given to the different variables in them. By assigning certain values to these, in a quite arbitrary manner, Mandel is able to show a system about to break down irretrievably. But he has no explanation as to why there should be in the equations his set of values,and not another set that might for .example, show the system continuing to expand for another 30 years. And because of this he leaves himself open to every reformist counter-argument. [4]

In desperation, Mandel moves to a third, and even more mystical argument. He suggests the system must break down with the introduction of automation because if all labour became skilled, technological labour, that ‘would imply a radical suppression of the social division between manual and intellectual labour ... (which) would undermine the entire hierarchical structure of the factory and economy, without which the extortion of surplus value from productive labour would become impossible. Capitalist relations of production would collapse.’

But capitalist relations of productions do not rest on the ‘social division of labour between manual and intellectual labour’ – that is part of the social democratic myth that identifies the middle class with the ruling class.

Capitalism rests upon the fact that one class owns (or controls) the means of production and another class (of both ‘intellectual and manual’ labourers) has to sell its labour power to them. Such a system does not live in fear of collapse because of a change in ‘the hierarchy’ inside the factory. Indeed, it can survive if ‘the hierarchy’ inside the factories is temporarily destroyed – providing the market relations between factories persists. For Mandel to pretend otherwise is to abandon Marxism for the wilder dreams of the once fashionable theorists of the ‘new working class’ and ‘self-management’.

The fact that Mandel has to try to hold this shaky theoretical structure together with mystical glue is not an accident. For the basic elements of the theoretical structure itself are faulty.

First, the notion that there is a ‘saving’ of capital over several boom-slump cycles. It is difficult to make any sense of this notion at all. When capitalists refuse to invest all their capital, the surplus does not accumulate indefinitely in some huge surplus hoard, waiting 30 or 40 years to be invested.

Instead what happens is that lack of investment leads to a low level of production; resources that would otherwise be used to expand wealth (labour, raw materials, factories) lie idle, indeed, they are often gradually destroyed (workers lose their physical strength and their skills, even starve to death; raw materials rot; mines fall in; factories rust). Additional surplus value that would flow to the capitalist does not flow; there are repeated crises that destroy the accumulated profits of whole sections of the capitalist class; in a desperate attempt to ward off further crises one national capitalist class wastes still more surplus going to war with another; the crisis is a crisis for the capitalists as well as for the workers.

The ‘hoard’, like so much else is subject to the ravages of the system. There is no automatic mechanism by which seven (or five) lean cycles lay the ground for seven fat cycles. There is no automatic regenerative mechanism, no ‘hidden hand’.

Nor is Mandel right when he claims that a new wave of innovations brought on steam by this accumulated surplus, makes it possible to evade the inner contradictions of the system as outlined by Marx ... The notion of innovation, of the ‘third technological revolution’ as being able to prevent the drive of the system towards crisis, even for a limited period (25 years) is a notion introduced into Marxism for the first time by Mandel. And it is nonsense. The classical Marxists had no doubt that the effects of accelerated technological progress would, be to increase not diminish the contradictions of the system.

As Lenin insisted,

‘The extremely rapid rate of technological progress gives rise more and more to elements of contradiction between the various aspects of national economy, to a state of chaos and crises.’ (Imperialism, The Highest Stage of Capitalism, London 1933, p. 28)

Mandel claims at one point that ‘a technological transformation of department I’ (i.e. production of means of production) could create ‘a constantly expanding market and the condition in which expansion did not itself rapidly lower the rate of surplus value and did not cause a decline in the rate of profit.’ But at best an improvement in technology can counteract the tendency for the rate of profit to fall in the short term only.

It is true that new methods of production can mean increased output of surplus value compared with real wages. Increased productivity means that it takes less labour time to produce the goods consumed by workers, and that therefore more surplus value can be produced for the capitalists without living standards falling or the working day being lengthened.

But this can save the rate of profit for a brief period only. For increased surplus value means more funds are available for investment. If these funds are used, then there will be a rise in the organic composition of capital. And, as Marx showed, there is no possibility of the increased surplus value obtained through rising productivity keeping up with the increase in the organic composition of capital.

The reason is simple enough. There is a limit to the amount of surplus value that can be produced by a given worker – the labour time for which he works. If he works eight hours a day he cannot produce nine hours worth of surplus value. But there is no limit to the growth of the organic composition of capital as successive outputs of surplus value are accumulated one on top of the other.

But there is no need for me to argue the point at any greater length here. For astoundingly, whilst Mandel bases much of his theory on the alleged ability of innovation to counter the trend for the rate of profit to fall, he lets slip in passing that

“An increase in the social average rate of surplus value has two contradictory consequences, which must ultimately generate a reduction of the social rate of profit ... It leads on the one hand to a growth in the accumulation of capital; on the other to a fall in the share of living labour in the total expenditure of labour. Since only living labour produces surplus value, it is only a matter of time before the increase in the organic composition of capital caused by accelerated accumulation surpasses the increase in the rate of surplus value. At that point the rate of profit begins to fall once more.” (p. 531)

In other words, an increase in the rate of surplus value due to increased productivity flowing from a ‘wave’ of innovations cannot stop the decline in the rate of profit for more than a short time. But if that is true, then much of Mandel’s theory is pronounced nonsense by ... Mandel.

The first series of this journal was associated with a view of why capitalism expanded for 30 odd years up to the late 1960s and why it is now in a new period of crisis – a theory usually referred to as ‘the Permanent Arms Economy’.

Mandel has a chapter on the Arms Economy. But he disagrees sharply with us about how it functions. The disagreement begins with Mandel’s explanation for the tendency for the organic composition of capital to rise and for the rate of profit to decline.

Mandel, like most writers, talks as if any improvement in technology involves coupling more machines with fewer workers. He says that is what causes the organic composition of capital to rise. But it just isn’t so, as numerous non-Marxists have had fun in demonstrating. Many innovations cut down the cost of machinery even more than the size of the labour force.

It is not technology as such that causes the rising organic composition of capital. It is the dynamic of the capitalist system as a whole and the way this effects the introduction of the new technology. Capitalism is the systematic pumping of surplus value out of the workforce. Competition between the capitalists means that every capitalist is under pressure to use the surplus value at his disposal (which he owns or can borrow) to gain a competitive advantage over his rivals.

A certain level of innovation may be possible on a low level of investment. But even more innovation, even more efficient technology, will be available with a higher level of investment. The most successful capitalist will be the one who makes this higher investment. A capitalist who does not use as much as possible of the surplus value in his possession to invest will fall behind in the competitive scramble. The greater the amounts of surplus value squeezed out of workers throughout the system, the greater the possibilities of capital intensive investments to increase competitiveness.

So the pressure is on for the average capitalist to increase the amount of investment compared with the size of the workforce – or, in other words, to increase the organic composition of capital.

But to see this, you have to explain the pressure to introduce new technology in terms of the dynamic of the system as a whole. You cannot begin, as do both Mandel and the revisionists, from the dynamic of technology in itself.

It is because Mandel is not clear on this that he disagrees with us over the functioning of the Permanent Arms Economy. For, for us, (as opposed, for instance, to writers like Sweezy) it is the effect of arms expenditure on the organic composition of capital in the system as a whole that explains how capitalism could avoid major slumps for 30 odd years.

How is this? The explanation we offer is quite simple. Arms are paid for out of the surplus value left in the hands of the capitalists (or their state) after they have provided for the consumption of workers, for raw materials and for the cost of renewing the productive apparatus. The greater the expenditure of surplus value on arms, the less the surplus value available for capitalists to invest in expanding the means of production.

The arms do not destroy surplus value – like the luxuries consumed by the ruling class they belong to the ruling class (through its state). They represent a change in the physical form of the surplus value, not the handing over of it to some other class (which would be what would have happened if instead of arms expenditure there was an increase in spending on hospitals, schools or some other component of the ‘social wage’).

Therefore increased spending on arms cannot change the ratio between social surplus value and social investment (the rate of profit).

The real effect of arms spending is to reduce the pressure on individual capitalists to use the surplus value to expand the means of production and to jack up the organic composition of capital. Therefore they reduce the long term pressure on the rate of profit. What is more, unlike the private consumption of the capitalist class, they exert a pressure on the capitalists in other countries to build arms also, thereby restraining their ability to expand their means of production.

However, there have been built-in limitations on the arms economy from the beginning. If a super-economy like that of the US spent vast sums on arms, an initially relatively small economy, like that of Japan, could live off exporting to the rest of the world without having to spend much on arms itself. The Japanese economy would grow faster than that of the US – increasing the relative importance of itself, a non-arms spender, in the world economy and pressurising other countries to spend less on arms so as to be able to compete with it in ‘pure’ market competition.

The result over 25 years was a decline in the proportion of world resources going into arms, a decline in the stabilising effect of this spending, and an increased tendency for the international system to re-enter a period of crisis.

On the basis of the Permanent Arms Economy you can easily arrive at an understanding of our present situation that does not depend on the mystique of ‘long waves’. But Mandel rejects this interpretation, although he does want to say the arms economy has played a partial role in stabilising the system. (He is no more prepared to take a hard line when he disagrees with us that when he disagrees with the fashionable would-be Marxists).

Mandel’s own argument over the arms economy is extremely curious. He says the arms economy cannot solve the realisation problem’ – the problem of how capitalism is to find markets. He then argues it cannot solve the problem of the rate of profit either. Indeed, he goes so far as to say it makes this problem worse (although he does not dare ask himself how the period of the highest spending by the US and Britain on arms was the period when they were least bothered by the rate of profit).

But then he insists arms spending does something else – it solves the problem of what he (or his translator) calls the ‘valorisation’ [5] of capital. By this he seems to mean the problem of finding a use for capital. This seems to be pure mysticism. Within capitalism there can be no ‘valorisation’ of capital, no use for capital, unless the problem of the rate of profit can be solved. For the only use for capital in the terms of the system is to expand itself, through making an adequate profit. Unless the arms economy provides an answer to the problem of the rate of profit, it cannot provide an answer to the problem of so-called ‘valorisation’. [6]

Mandel rejects, the central role of arms spending in maintaining the rate of profit, because he has a hopelessly confused notion of how arms spending takes place. He argues that the more there is investment in arms industries, the more there will be a tendency for the rate of profit, to fall, since these industries tend to have a high organic composition of capital. ‘Investment of capital in Department III (the arms section – CH) raises the organic composition of capital there.’

The capitalists in Department III expect the same rate of return as capitalists in other sectors. But production of surplus value per unit of investment will be less in this sector (because it has a higher organic composition of capital: fewer workers operate more machinery, etc.). Therefore, they can only get the rate of profit they expect if the average throughout the rest of industry is lowered to pay them.

The argument looks convincing – on the surface. But how then can you explain the fact that in peacetime periods of highest spending on arms the rate of profit has not fallen at massive speed? There is only one explanation. It is to recognise that not only the profit of the capitalists in Department III, but also the wages and the cost of raw materials and machinery has to be paid for by the capitalists in other industries. For resources are provided from the rest of the economy for these things, as well as for the arms capitalists’ profits without anything being given to the rest of the economy in return.

The arms workers produce nothing of benefit to the rest of the economy. Their pay is a deduction from the total social surplus value. The machines in the arms factories pass their value into goods that are then destroyed: they have to be paid for out of the total social surplus value. In this respect the profits of the arms capitalist are no different from the wages of the arms worker or the expenditure on machinery and raw materials for arms.

This is shown empirically by the way profits are fixed in arms manufacturing. They are not determined by the market, by the supply and demand of arms, the flow of capital into and out of arms manufacturing. They are fixed by a decision of the state to pay the arms companies a rate of profit equal (or a little above) that which has already been determined for the rest of the economy by the laws of the system. If the organic composition in the rest of the economy is low, the rate of profit there will be high, and therefore the rate of profit given by the state to the arms manufacturers will be high.

So the real question is not, as Mandel puts it as to whether profit rates in arms production cut the average rate of profit. It is whether any arms spending cuts the profits at the disposal of the capitalists, and therefore the rate of profit. After all, arms spending means that instead of being able to pocket all of their profits, the capitalists are forced to pay a fair amount in tax to the state.

But we must not forget that the state is the ‘executive committee of the bourgeoisie’. The taxes the capitalists pay to the state are paid to themselves as a collectivity (although an individual capitalist might not always recognise this). That is why arms spending is in some ways like luxury consumption by the capitalist class: it is what the ruling class chose to spend their profits on once they have made them.

If I have a hundred pounds in my pocket and spend £50, that does not mean that I didn’t have the £100 in the first place. If the total social surplus value equals, say, 200 billion dollars, the fact that the capitalist class chooses to spend half that on arms does not mean that the initial 200 billion really was 100 billion. Arms expenditure no more reduces the rate of profit than does expenditure on investment or on the luxuries of the rich. To claim otherwise is to confuse the production of surplus value with its utilisation by the capitalist class.

Mandel just doesn’t grasp the contradictions in the arms economy. He accuses Mike Kidron of the ‘truly astounding discovery that the arms economy is a factor that slows down late capitalist growth.’ But you only have to take a cursory glance at the statistics for arms spending and economic growth to see that the economies that have borne the greatest share of the arms burden have been those with the worst growth records:

|

|

Arms Expenditure |

Economic |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

1955 |

1970 |

||

|

US |

13.4 |

9.9 |

93% |

|

UK |

7.7 |

4.9 |

54.7% |

|

France |

4.9 |

3.3 |

176% |

|

Germany |

3.2 |

3.2 |

224% |

|

Japan |

— |

about 0.5% |

265% |

Japan, West Germany etc. have been able to depend upon the US arms budget to stabilise the international capitalist system, while bearing relatively little of that burden themselves. The result is that Japan in particular has been able to devote nearly twice as much of its national product to productive accumulation than the arms-spending states. If all the advanced western states had behaved like Japan, there would have been an initial burst of growth at Japanese type rates – only to be followed by a catastrophic increase in the organic composition of capital, catastrophic falls in profit rates and catastrophic slumps.

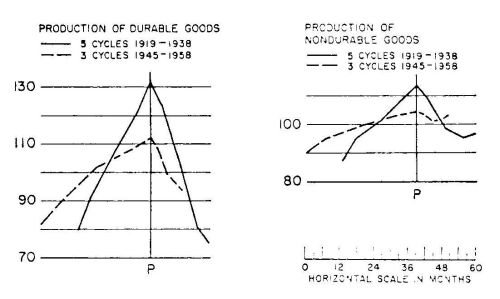

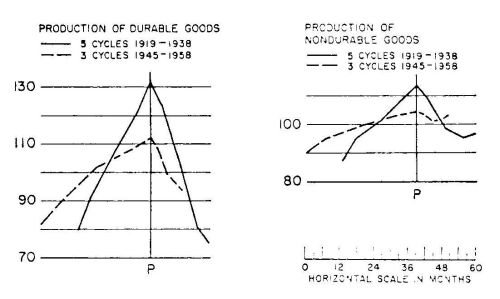

The point can be illustrated another way, by comparing the behaviour of the US economy in two periods: (1) in the pre-war years when there was hardly any arms spending; and (2) in the post-war years when there was a very high level of arms spending.

|

|

(Source: R. A. Gordon: Business Fluctuations, New York 1961, p. 272) |

It can be seen that the rate of growth in the pre-war booms was greater than since the war – there was no arms spending to dampen the rate of accumulation. But precisely because of this, they were followed by much sharper slumps than in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.

Mandel fails to understand any of this. As a result, he is forced like any bourgeois economist to look for some mystical explanation of the expansion of the system in the 1950s and its stagnation and crises today. That is why he ends up going back to the magic cycles of Kondratieff. But having taken that step he cannot deal with the revisionists and reformists who are trying to destroy the revolutionary kernel of Marxist economic analysis. Instead he is forced, as we have argued above, to try to compromise with them, to replace explanation by eclecticism.

The result is not a book that is a guide to practice but a somewhat tedious work that leaves unexplained the major features of modern capital. Mike Kidron described a previous book of Mandel as ‘a Marxist failure’. Unfortunately, the same verdict has to be recorded here.

(Page references, unless otherwise specified, are to the NLB edition of Ernest Mandel’s Late Capitalism.)

1. Interestingly a number of the objections I found myself making in writing the first draft of this review I found were made independently by Bob Rowthorne in his review in New Left Review. Rowthorne, however, draws diametrically opposed conclusions from his objections to those drawn by me. He replaces Mandel’s account of the crisis by one which permits of reformist answers to the crisis, whereas I will argue the crisis is more, not less deep rooted than Mandel claims.

2. ‘Revisionist’ not as an insult, but in the strict sense of abandoning fundamental tenets of Marxism, like the labour theory of value an the tendency towards a falling rate of profit.

3. For the latter, see C. Harman, Poland and the crisis of State Capitalism, IS 93 and 94.

4. Which people like Rowthorne are only too happy to provide.

5. ‘Valorisation’ is the trendy new translation of Marx’s term Verwertung. My German dictionary gives the meaning of this term as ‘utilisation’, including the utilisation of machinery.

6. I note that Bob Rowthorne is as bemused as me by Mandel’s contradictions over this point – although his conclusions are of course quite different..

Last updated on 29.2.2012