MIA > Archive > P. Foot > Why you should be a socialist

‘Without struggle there is no progress; And those who profess to favour freedom, yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without digging up the ground. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its waters.’

Frederick Douglas, Black American freedom-fighter

|

The leaders of our great trade unions find themselves in a very similar situation to that of Labour MPs. They represent some eleven million people, who, with their families, make up at least half the British population. The trade union leaders want to assist these eleven million; to get more wages and benefits and social services for them out of the wealth which they produce.

They want to do this by negotiation. George Woodcock, general secretary of the Trades Union Congress, told the TUC in 1963:

‘We left Trafalgar Square long ago.’

He meant that the days for mass demonstrations were over. These, he argued, are the days of negotiations by skilled, graduate trade union leaders with skilled, graduate employers – out of which a fairer society will be fashioned.

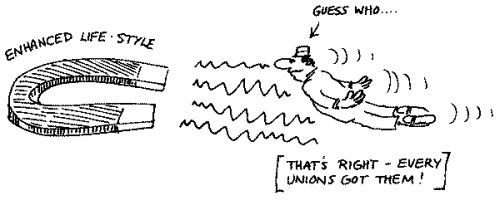

The belief that skilful negotiators will get more for the workers than unskilled negotiators leads to a simple conclusion: that the trade unions need higher-paid, more skilful leaders. So the trade union leaders turn to Oxford and Cambridge for bright young men whom they can train in union research departments and convert into trade union officials.

It follows, too, that skilful negotiators should not be subjected to the risk of election. They must be appointed by their skilful predecessors. They must also be offered high pay and perks.

Very few trade union officials are elected. Almost all of them are appointed by a small committee, itself often dominated by full-time officials. All full-time officials in Britain get paid more, often very much more than the people they represent.

More than sixty years ago, in their history of the British trade unions, Beatrice and Sydney Webb quoted an old engineer on the ‘change’ which comes over workers on the shop floor when they take up union positions.

‘Nowadays, the salaried officer of a great union is courted and flattered by the middle class. He is asked to dine with them and will admire their well-appointed houses, their fine carpets, the ease and luxury of their lives. He goes to live in a little villa in a lower middle-class suburb. The move leads to his dropping his workmen friends ... His manner to his members, and particularly to the unemployed who call for a donation, undergoes a change.

‘He begins to look down upon them all as “common workmen”, but the unemployed he scorns as men who have made a failure of their lives; and his scorn is probably undisguised ... At last the climax comes. A great strike threatens to involve the society in desperate war. Unconsciously biased by distaste for the hard and unthankful work which a strike entails, he finds himself in small sympathy with the men’s demands, and eventually arranges a compromise on terms distasteful to his members. The gathering storm-cloud now breaks.

‘At his next appearance before a general meeting cries of “treachery” and “bribery” are raised. Alas! It is not bribery. Not his morality but his intellect is corrupted.’

|

What was true all those years ago is even more true today. Top trade union leaders see themselves not just as negotiators for their members to win concessions from the profit system, but part of the profit system itself. Norman Willis, assistant general secretary of the TUC, asked a special Congress on 16 June 1976:

‘Why do we dig the system out? We did not invent the system; a lot of us do not like it. So why the hell do we dig it out?

‘We dig it out, brothers and sisters, because our members are in it and working in it everyday.’

Willis was speaking to a motion commending the second stage of voluntary pay restraint which the trade union leaders had just agreed with the government. The restraint meant serious cuts in living standards for all trade unionists, especially the lower paid. The six trade union leaders who had agreed the deal with the government had arrived in the early stages of the talks – in May 1976 – with a list of ‘concessions’ which they wanted in exchange for pay restraint: increases in pensions, consolidation of pay increases into basic rates, free school meals. At each meeting, the Chancellor of the Exchequer read them a lecture on the dreadful state of pound sterling. The country, he said, was in peril. This was not a time to talk of concessions. The union leaders meekly agreed to withdraw the demand for concessions. They emerged with nothing but a government promise not to increase the price of school meals, a promise which was quickly broken when the Chancellor announced a new set of public spending cuts three months later.

How was it possible for the unions to agree drastic wage restraint without a penny’s worth in return for their members? Because they identified with the profit system. They wanted it to survive and grow so that they could reform it or at least negotiate with it. When told that the system was in crisis, their immediate reaction was to save the system first, and worry about their members second. Thus their members’ standard of living was sacrificed.

David Basnett, general secretary of the General and Municipal Workers, admitted as much at the 16 June TUC: ‘If there is a drowning man,’ he said, ‘you beat inflation. Then you build your economic and industrial strategy.’

The ‘drowning man’ on this occasion was the profit system. The lifelines were unemployment, wage cuts, public spending cuts, higher investment grants, price control relaxation, abolition of corporation tax.

The problem with all this is that the profit system and its supporters have no equivalent concern for the people they exploit. They see drowning men and women every day: starving people, unemployed people, disabled people, sick people. Yet there is no national call for ‘lifelines’ to them.

The class with property fight an endless, furious class war, and they use the Basnetts, the Jack Joneses, the Scanlons and the Labour governments to help them out. Once saved from drowning by the sacrifices of working people, they do not show their gratitude by employing more of them or paying them higher wages. They rise up refurbished and seek to clobber the unions.

In 1926, goaded by the most savage cuts in the miners’ wages, the union leaders played their highest card: they called the entire working class out in a general strike. The Tory government let them call the strike, and sat back smiling, almost challenging: ‘You’ll get no concessions from us’ they said. ‘Now what will you do: call off the strike or carry the workers to a revolution?’ After nine days of hope and activity among workers everywhere, the TUC called them back to work without a single concession.

The trade union leaders are the doctors of capitalism.

They prefer almost any amount of sacrifice for their members to an overthrow of the society with which they are negotiating. The same David Basnett wrote in The Times on 25 September 1975:

‘We are not seeking a revolution, which would destroy the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of our members.’

Instead he seeks to destroy the livelihood of thousands of his members by negotiating wage cuts and spending cuts on their behalf.

There is a story which explains why. It tells of a militant left-wing trade union official who faces a group of angry workers on strike. ‘Don’t worry, girls,’ he says, ‘I’ve got this boss on the run. I can get you an extra £5 a week.’ A voice from the back of the hall calls out ‘Not enough.’ So the negotiator goes back to negotiate. A few hours later, he’s back again in front of his workers. ‘You won’t believe this,’ he says, ‘but I’ve done the impossible. He’s agreed to £10 a week.’ The same voice from the back of the hall calls out. ‘Still not enough.’

‘Well,’ cries the official in desperation, ‘what is it that you want then?’

The voice answers: ‘We want a social revolution.’

‘But,’ stammers the trade union official, ‘management will never agree to that.’

Precisely.

Last updated on 8 May 2020