Pierre Broué & and Emile Témime, La révolution et la guerre d’Espagne, 1961.

© Pierre Broué, Les Editions de Minuit, 1961.

Translated by Tony White.

Published 1970 by The Massachusetts Institute of Techonology, Paperback 2008 by Haymarket Books.

Transcribed by Martin Fahlgren.

Marked up by Martin Fahlgren & Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

We were ten years old in 1936. To us, the Spanish Civil War was, first of all, a shock, the sight of thousands of emaciated men, women, and children, hungry and often ragged, the Spanish refugees. Disturbing words, charged with anguish, fell from grown-ups’ lips: Hitler, air raids, the fifth column, the war. So the war itself did not come as a surprise to us: we had, if not understood, at least sensed, quite simply, that these crowds of Spaniards had been through it before ourselves. Later on, Spanish comrades, for whom the struggle had never ceased, informed us of the end of their hopes; Franco had survived the collapse of the dictatorships.

It was the vagaries of academic life that led to our meeting at the Lycée Condorcet, both of us having been attracted for some years by the Spanish Civil War, which one of us saw as the neglected, distorted preface to the Second World War, the other as a workers’ and peasants’ revolution, disfigured, betrayed, and stifled. We were in agreement only on the need to work, and it was for this very reason that we undertook, while there was still time, to listen to the survivors, both observers and protagonists, and to write a history of the Revolution and the Spanish Civil War from 1936 to 1939. We intended, in the face of ignorance, neglect, and falsification, to recreate this struggle in the most truthful possible way and to rid it of the legend that had prematurely buried it. Today we realize that this objective, once attained, is but a first step in the compilation of a more complete history, which would require thousands of eye witness accounts and, even, documents from archives that are still inaccessible, whether in Spain herself, France, Great Britain, the USSR, or the Vatican.

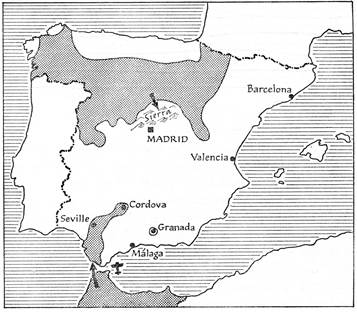

It would be wrong to expect more from our work than we intended, more than we could include in it. Those readers to whom, we hope, we have conveyed the feeling of Spain will have to look elsewhere, to experts on Spain, for answers to the questions that will arise when they start reading us. We suggest that they go and look in geographical works for a detailed description of this country that is a world apart, as African as it is European. ‘Spain,’ wrote Joan Maragall, is ‘as far from the world as a lone planet. And its people, who are in the world, seem forgotten.’ They will then learn that Spain is a ‘homespun cloak fringed with lace,’ that she covers 506,000 square kilometers, that her population consists of almost 30 million inhabitants, that she ‘survives with difficulty’, that ‘her production is inadequate for a very frugal people’, and that she lacks capital and means of transport. [1] If they pursue their investigations into history books, they will learn that the ancients placed the Elysian Fields in Spain, that Strabo, the first geographer, called Andalusia the ‘dwelling of the Elect,’ and that Muslim Spain, because of her agricultural and craft techniques and her scientific and philosophical knowledge, was in the vanguard of civilization in the Middle Ages. They will also learn that the ravages of the Reconquista, the first trial of strength between a prosperous if exhausted Muslim world and a barbaric Christian West teeming with life, did not prevent Spain from becoming mistress of the Old and the New Worlds: in all the books, the age of Louis XIV follows that of ‘Spanish dominance.’ But they will also be reminded that the Golden Age of Spain, as Gaston Roupnel called it, was both a ‘fount of pride and vale of tears, according to whether one considers its potentates or its masses, its Court or its vast, wretched territories stretching from frontier to frontier.’

Perhaps then our readers will find their way more easily into the Spain that ‘shrinks back as you approach her,’ as Dominique Aubier and Manuel Tuñon de Lara tell us. [2] With them, they will be able to negotiate the difficult journey toward ‘the subterranean unity that forms the bone structure of a Spaniard, whether he be loquacious and Andalusian, severe and Castilian, crafty as a gallego, self-interested as a Catalan, or industrious as a Basque.’ They will learn the words ‘that make up the Spanish reality’: tierra, the earth, ‘which gives life but does not maintain it,’ hambre, which we translate as ‘hunger,’ but ‘which is to our hunger what rage is to anger,’ castizo, inadequately translated as ‘of good race,’ whereas it daily affirms the craving for dignity that emanates from the whole history of the Spanish peoples. Perhaps they will also grasp what, more than anything, defies description and explanation, the place occupied by death in the life of the Spaniard, whose passion for toros will have already hinted at its importance. They will pursue their inquiry still further, in order to fathom the profound spirituality that goes hand in hand with the most fanatical faith and virulent anticlericalism. They should learn about the land of the Inquisition, of auto-da-fé, in which the act of burning a man – whether ill-converted Moor, baptized Jew, secret Protestant or enlightened spirit – was termed ‘an act of faith.’ They should pause for a long while in front of Goya and the Dos de Mayo drawings, to ponder the violence and the death of these bare-handed men facing the guns of the firing squad or the sabers of the Mamelukes. They will not easily forget the uprising against Napoleon by this people whom he called ‘beggars’ and will note that, while the great fawned on the conqueror, the peasants, in their village assemblies, declared war on the Grand Army and coined the word guerrilla. They should spare a few moments for the siege of Saragossa, captured by the French in fifty-two days, house by house and floor by floor, and for its 60,000 victims, including women and children, because they too were combatants. They should listen to Marshal Lannes: ‘What a war ! Having to kill such brave people, even if they are mad !’ Because these madmen fought with their fists and their teeth. They will stumble on this violence again in the Carlist wars, in all the nineteenth-century civil conflicts, in the Royalist repression that sickened even the French Ultras who had come in the name of the Holy Alliance to crush the Spanish Revolution (the first one) in peasant uprisings, in strikes and repressions, and in the tortures and the ‘exploits’ of the Civil Guard immortalized by Federico García Lorca’s Romancero.

In discovering this Spain, they will discover thousands. They will learn that the same Castilian word, pueblo, stands for both people and village and that the village is a small homeland, Brenan’s patria chica, living its own almost autonomous life. Then they will be prepared to follow, in Rama’s works for instance, the laborious construction of a state on top of an incomplete nation, the vanity and artificiality of this ‘liberal’ enterprise in a country where caciques and señoritos still hold sway. Because the caciques, those local tyrants, are not merely the traditional bailiffs of the large estates, using their delegated authority to slake their lust for power and to crush at will and contemptuously those whom they employ and control. ‘Caciquism’ has permeated the whole of social and political life: the administration, the parties, and to some extent the unions, the fact being that this vice of medieval society can still be spontaneously secreted by twentieth-century Spain.

No doubt our readers will then have a better understanding of certain distinctively Spanish features of the Revolution and the Civil War, the arrogance of the nobility, confident of embodying a superior race, the contempt for death and the ferocity in battle of all the combatants, their particularism and their attachment to their towns, their villages, and their soil – what is known as ‘individualism,’ ‘lack of discipline,’ and ‘anarchist tendencies’ – the violent fanaticisms, the hatred, and the mistrust that binds social hierarchies, but also the constant affirmation of dignity, the part played in the lottery of war by each contestant’s idea of man – hombre, an interjection and an affirmation – whom they wish to exalt and ‘liberate’ or attack and destroy by systematic humiliation.

Preliminary researches into our subject suggested many routes that a Hispanist might take. A Spanish woman friend, once deported to Germany, proposed that we should describe, after a scientific study, what she had witnessed in her own life and in the files of the dead, the long journeys by peasant groups from their pueblo to the front and then, still together, to the death camps. No doubt this would be a perfectly Spanish way of writing the history of the Revolution and the Spanish Civil War, and it would have brought us closer to the secret reality, the collective soul of the people during those terrible years, and nearer to an understanding of what this drama meant to the millions of individuals who comprise the ‘masses.’

However, we did not chose to approach Spain by this path. First, because we are not genuine Hispanists. Second, because the preoccupations that bound us to this work extended far beyond the context of Spain alone. We have not tried to understand everything, still less to explain everything, neither Boabdil nor Avicenna nor Don Quixote nor Torquemada nor even Ignatius Loyola. Our intention was to confine ourselves to facts that were perhaps simpler, but above all universal. Spain is Spain, of course, but she is also one of those countries that were once known as ‘backward’ and that today have been hypocritically rechristened ‘underdeveloped’ countries. All the tests that the modern economist applies to countries to reveal the characteristics of ‘underdevelopment’ place the Spain of 1960, like the Spain of 1930, among the most populous and poorest nations, those of which it cannot be seriously maintained that their poverty bears any relation to the opulence of the rest. In spite of the unreliability of Spanish statistics, it is clear that it is only with great difficulty that Spain attains an average of 2500 calories a day per inhabitant, the minimum below which undernourishment occurs. Infant mortality remains high. Life expectancy at the age of one is fifty-five, more than in India, of course, but far less than in the West. The birthrate remains healthy. The number of illiterates is still considerable. The proportion of the ‘active population’ does not exceed 37 percent, mainly agricultural workers. The inferior position of women is underlined by the fact that only 9.4 percent of them can be classed among the active population. Child labor is still widely practiced. The middle classes are numerically small. The average national income is half that of the French, and there are far greater divergences in the social scale. According to Professor Birot, Madrid includes 300,000 servants among its 1,800,000 inhabitants.

As in the other backward countries of the world, mineral wealth A and industrial development in Spain are in the hands of foreign capitalists, except in some subsidiary sectors. Big proprietors and middle-class businessmen form a small oligarchy, wholly preoccupied with defending its privileges. The Church’s only mission seems to be the one attributed to it by the hardly religious Napoleon I, to acknowledge ‘inequality of wealth’ and to accept the fact that ‘one man dies of hunger alongside another who is gorging himself.’ The teaching of history, in the Spain of 1960, just as a hundred, thirty, or twenty years ago, devotes a hundred pages to counter-reform and one – and what a one ! – to the French Revolution. In short, the Revolution and Civil War in Spain were merely a bloody and violent interim period. They simply inspired great fear and made the regime of the ruling class harsher. Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship, which held sway (under the aegis of the Spanish monarchy) until 1931, to the proclamation of the Republic, was replaced by a more absolute dictatorship. The Republican experiment did not convince anyone, and the weak state, which did not succeed in reforming Spain or even in really becoming organized, was the first victim of the events of 1936. The soldiers’ victory robbed it of all hope of revival in the near future. In an authoritarian state, the army dictates its own laws, and it will never be adequately stressed what weight is carried in such unessentially stable countries by armies, which are good only for civil war and for the preservation of an appointed order.

It is not, in the twentieth century, a feature peculiar to Spain to contain a mass of landless and impoverished peasants, on the border of survival, who fling themselves all the more willingly into the struggle because they have all to gain and nothing to lose; nor is the existence of a working class, still closely linked with the peasantry and made up chiefly of laborers and nonspecialist workers, in which there is practically no ‘working-class aristocracy’ apt to temper the aggressive impulses of the masses, rough but capable of sacrifice. It is not only in Spain that such workers and peasants have set themselves up as the shock troops of the revolution that the bourgeoisie refused to fight through fear of the future: the twentieth-century third estate, even though it was dubbed ‘popular front,’ everywhere cracked very quickly under the impact of the ‘fourth estate’ of workers and poor peasants, fighting on their own behalf. Nor is Spain the only country to have provided a striking demonstration of the popular trend towards direct democracy. The same determination to wield power through people in arms already existed among the Paris sans-culottes in 1794. [3]

Those who cry ‘Eternal Spain’ at the sight of the militias of the Republic with their elected workers’ leaders and their high-flown titles should remember the Paris Commune and its Federates, its elected officer-militants, its ‘Commune Turcos,’ its ‘Avengers of Flourens,’ and its ‘Lascars.’ For it is not only in Spain and in Cuba that revolution is romantic. Need one recall that it was in Russia in 1905 that the first ‘councils’ emerged – where, as in Spain, parties and unions, sitting by virtue of their qualifications, had equal representation – and that the word, in Russian, is translated as soviet? Need one, nearer to our own time, invoke the role played in 1956 by the ‘Revolutionary Committees,’ the ‘Workers’ Councils,’ and the ‘Central Workers’ Council’ during the Hungarian Revolution?

Moreover, the Revolution and Civil War in Spain were far from being an exclusively Spanish affair. From near or far, all governments had a hand in them, intervention and non-intervention being founded on immediate interests, and strategic and diplomatic preoccupations, but also on general interests, those known as ‘historic.’ The affairs of Spain could no more be settled within her own frontiers than could those of Korea and the Congo yesterday, and those of Cuba, and Vietnam today. Such civil strife ultimately involves all powers and all peoples, because it is merely a particular aspect, in a precise geographical context, of the crisis that is rocking humanity in the century of world wars.

Jean Jaurès, who was also a historian, admitted that he would gladly have sat alongside Robespierre during the Revolution. We shall be equally frank. There has never been such a thing as a perfectly objective historian, and anyone who thinks he is One is lying to himself just as he lies to others. All the precautions with which scientific research and criticism are surrounded do not in the long run suppress either our feelings or our personal reflexes. Why hide it? The choice of subject itself reveals our deepest sympathies. We, too, having ‘lived’ our subject, were inclined to take sides: though in spirit we were on the same side of the fence, we willingly parted company, one of us more in sympathy with the progressive Republicans and the moderate Socialists in his concern with organization and efficiency and the world balance of power, and the other with the dissident Communists and revolutionary Socialists, because he felt, like St. Just, that ‘those who fight revolutions halfheartedly are merely digging their own graves.’ Our division of labor is proof of it. The Revolution is the subject of Part I, edited by Pierre Broué, whereas Emile Témime dealt with the international aspects of the war, as well as with the birth of the National-Syndicalist state. However, it should not be thought that our book is the result of a juxtaposition of two accounts on related themes. We intended these two parts to be distinct in order to emphasize two points of view – in our mind the most important – from which the study of our subject can be approached. The main disadvantage of this method is to produce unavoidable repetitions, which we have however limited as far as possible. [4] Its advantage is that this dual clarification may shed a more revealing light on events, illumine their complexity yet not overload the exposition with comment and flashback. During the three years of our collaboration, we have made daily comparisons of our points of view, exchanged our notes and index cards, criticized our documents and interpretations, forcing each other into fresh researches and, in the final stage, successively fruitful editing. May we be forgiven if, being our own first readers, we feel it our right to maintain that this collaboration, our sometimes lively though always friendly mutual criticism, is proof of the conviction and the seriousness we brought to our common task. We think that we have made our point, at least to the extent that this is possible with the only printed sources, already vast, that could be placed at our disposal. Whatever their origin, we have tried to judge them as historians and to eliminate all prejudice, to set out the facts honestly while passing only a minimum of judgments; we hope thereby to have given everyone the opportunity to stress one or another aspect of primary concern to him. This is why we shall be glad to listen to objections, criticisms, and fresh evidence, all of which, in and through our work, may contribute toward the truth, which in our view can only be the fruit of constant research.

All that remains for us – and it is not the least of our duties – is to thank all those without whom this work would not have seen the light of day: Jérôme Lindon, Director of the Editions de Minuit, our friends on Arguments, Edgar Morin and Kostas Axelos, who introduced us to him, and, above all, our coauthors, all the witnesses, Spanish and non-Spanish, politicians, writers, and workers, in Europe and America, too numerous to be mentioned, who have responded to us, ransacked their memories and their records, devoted hours to our questionnaires, and searched for unpublished documents and missing witnesses. Their sole concern, in spite of the diversity of their political outlooks, has been to help us in our search for the truth. We are especially grateful to Jordi Arguer, who placed his library and document collection, unique on this subject, at our disposal and helped us with his advice. Finally, Jean-Jacques Marie translated Russian material for us.

Acción Popular: Conservative Catholic party.

Alliance of Anti-fascist Youth: Alliance, in early 1937, of the majority of the JSU and ‘Republican’ Youth.

Asaltos: Republic Assault Guards.

AVER: Association of Volunteers for Republican Spain.

Camisas Viejas (‘Old Shirts’): Veterans of the Falange.

CEDA (Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas): Spanish Confederation for Autonomous Rights.

CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo): National Labor Confederation (Anarcho-syndicalist Union).

CTV (Corpo Truppe Volontarie): Italian Expeditionary Corps.

Esquerra: Catalan Autonomist party.

Euzkadi, Nationalist party of: Basque Antonomist party.

FAI (Federación Anarquista Ibérica): Iberian Anarchist Federation.

Falange: Spanish Fascist organization.

Flechas: Falange Youth.

GEPCI (Federación Catalana de Gremios y Entidades de Pequeños Comerciantes y Industriales): ‘Syndical’ organization of small tradesmen and manufacturers, belonging to the UGT.

HISMA (Compañía Hispano-Marroquí de Transportes): German company in charge of relations with Nationalist Spain.

IC: Communist International (Comintern).

JC: Communist Youth.

JCI (Juventud Comunista Ibérica): Iberian Communist Youth (POUM Youth).

JL: Libertarian Youth.

JONS (Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista): National-Syndicalist Offensive Juntas, which merged with the Falange in 1934.

JS: Socialist Youth.

JSU Unified Socialist Youth (after the merger in 1936 of the JS and the JC).

Lliga: Catalan bourgeois party.

NKVD (People’s Commissariat for International Affairs): Russian secret police (OGPU).

PCE: Spanish Communist party.

POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista): Workers’ Marxist Unification party.

PSOE: Spanish Workers’ Socialist party.

PSUC: (Partido Socialista Unificado de Cataluña): Unified Socialist party of Catalonia (from 1936).

Requetés: Carlist military organization.

Revolutionary Youth Front: Alliance, in 1937, of the JCI and the JL.

SEU (Sindicato Español Universitario): Spanish University Union (founded in 1937).

SIM (Servicio de Investigación Militar): Republican secret police.

Single party: The only Nationalist party after April 1937.

Tercio: Spanish foreign legion.

Traditionalist Community: Carlist Monarchist party.

UGT (Unión General de Trabajadores): General Workers’ Union, of Socialist origin.

Spain, at the beginning of the twentieth century, was the anachronism of the West: she was an oasis of tradition in an increasingly uniform world, and her masters were proud of having preserved her Hispanidad in spite of modern political and economic trends. Yet it was in this country, deeply entrenched in her past, that in 1936 the last interwar revolution broke out. Like Russia in 1917, Spain was at the time the weakest link in the capitalist world; here, however, the similarity ends. Unlike the October Revolution, the Spanish Revolution was not the first spark in a growing conflagration but the last flicker of a fire already extinct throughout Europe. The Russian Revolution had heralded the end of the First World War. The Spanish Revolution merely provided a rich testing ground for the powers then preparing for the Second. The revolution that turned into a civil war was in the end merely a dress rehearsal for World War II.

Czarist Russia owed her extremely backward character to the slowness of her general economic development. Spain, by a curious paradox, owed hers to the direct consequences of her lead over the other European powers at the beginning of modern times.

During the period when her hegemony over Europe coincided with her dominance of world trade, her Monarchy was becoming centralized and her regional characteristics were growing blurred: feudal Spain was on the wane and a modern state was emerging. But the very precocity of this expansion recoiled upon her. The discovery of America and the creation of a vast empire in the New World contained the seeds of decadence. While precious metals brought home by the King’s galleys infused Western Europe with fresh blood, it was as if the home country were paralyzed, becoming ‘the vale of tears’ as well as the ‘fount of glory’ described by sixteenth-century historians. In the nineteenth century, Spain lost her remaining world outposts and was in the end barely touched by the industrial and liberal revolution that succeeded in transforming the old Europe.

The classes in the old regime continued to disintegrate, without however completing the formation of the emergent bourgeois society. The slowness of capitalist development and the withering of economic relations acted as a brake on the formation of the nation and strengthened centrifugal trends and the separatism of the provinces: businessmen in the Basque provinces and Catalonia, who had benefited from restricted industrial development in the nineteenth century, bore the yoke of Castilian oligarchy with impatience but had no means of shaking it off. The mass of proletarianized peasants sometimes gave vent to their anger in violent outbursts, actual peasant uprisings in the midst of the machine age. Still linked in a thousand ways to the peasant world, a proletariat, stimulated by the same aggressiveness, began to organize itself. Thus, the seeds of destruction of a past so alive and so burdensome that at the beginning of the twentieth century it seemed eternal were building up in every pore of a complex society.

At the turn of the century, Spain was a basically agricultural country. More than 70 percent of her active population was engaged in agriculture. The Spanish peasant used the same implements as his forebears in the Middle Ages: throughout most of the country the hand plow was preferred to the horse plow. The yield per acre was one of the lowest in Europe, and more than 30 percent of the arable land lay fallow.

Industry, where it did exist, had barely emerged from the manufacturing age. There was very slow progress in industrial concentration: only the iron and steel works in the Basque provinces bore any resemblance to the heavy industry of capitalism. In Catalonia the textile industry, the most important in terms of total output, was still split up into a mass of tiny business firms.

Spain had nothing to offer on the world market except the products of her soil and subsoil, in return for manufactured goods from foreign industry. But she was also – an inevitable corollary – fertile ground for foreign capital invested several decades earlier in the most substantial and profitable sectors:

The First World War brought Spain relative prosperity by providing her with trade outlets. She became at one and the same time a supplier of foodstuffs and even, to some extent, of manufactured goods. But the return of peace drove her out of the world market, where she was unable to compete with the industrial powers. The 1929 world crisis hit her hard: customs tariffs imposed by the great powers meant that she could not export her agricultural produce and brought about the collapse of her domestic market, already barely able to absorb the products of her national industry. Countries like Spain, with a semicolonial structure, were probably even more affected by the crises of the thirties and their social repercussions than were the more advanced countries. [7]

Extremes in social differences aggravated the slightest economic setback and hardened an organism whose chances of adaptation were already limited. As Henri Rabasseire [8] estimated, of the eleven million Spaniards making up the country’s active population, there were eight million poor, whose work provided no more than subsistence: a million small craftsmen, two to three million agricultural workers, two to three million industrial workers and miners, and two million tenant farmers or small rural proprietors. Between this mass and the million members of the privileged class, whom Rabasseire called ‘parasites’ – officials, priests, military, intellectuals, big landowners, and the upper bourgeoisie – were sandwiched fewer than two million members of the ‘middle class,’ half of them well-to-do peasants, the other half members of the petty bourgeoisie concentrated in the more advanced centers, such as Barcelona, Valencia, Bilbao, and Santander.

No expansion was possible while these eight million poor workers had no alternative except to try and survive painfully in unvarying living conditions, with expenditures reduced to a strict minimum and a budget devoted mainly to food. The development of means of production within the framework of capitalism was sealed off from outside by customs barriers, or the competition of the great powers, who denied Spain a market. At home, the creation of a solid and prosperous peasantry would have permitted the formation of a domestic market. But this presupposed the solution of Spain’s chief problem, that of land. It was in the rural areas that the fiercest social antagonism existed and that secular hatreds were fostered.

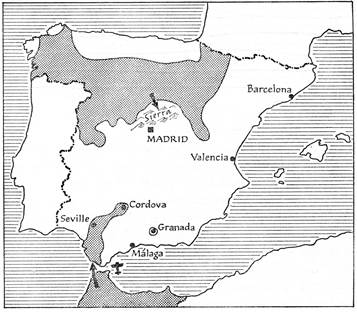

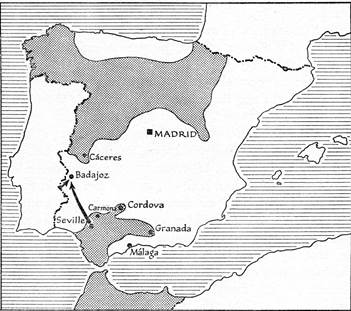

In 1931, two million agricultural workers owned no land at all, whereas 50,000 members of the gentry owned half of Spain’s acreage. While 1½ million small proprietors whose land did not exceed 21 acres were forced to work on the estates of the big proprietors in order to live, 10,000 landowners owned more than 250 acres each. In certain provinces, the big landowners were in complete control: 5 percent of the landowners in the province of Seville owned 72 percent of the total; in the province of Badajoz, 2.75 percent of the landowners owned 60 percent. It was common knowledge that the Duke of Medinaceli owned 200,000 acres and the Duke of Peñaranda more than 125,000.

Yet the overall picture of the condition of the land and the peasants was infinitely more complex than these crude figures might suggest. The agrarian systems varied according to natural conditions, especially the degree of drought. These different forms of tenure were also the result of centuries-old battles among the peasants for land. Between the seasonal worker and the small independent proprietor was a whole spectrum of farmers and tenant farmers, with leases of varying length, and of small proprietors compelled to pay dues that derived straight from the medieval feudal regime. Thus, as Gerald Brenan [9] pointed out, there were two basic agrarian problems: the smallholdings in the North and the Center, often too small for subsistence, and the large estates in the South, developed through the work of laborers who were kept at starvation wages through the plentiful supply of manpower.

The small proprietor in Asturias, who benefited from the addition of vast stretches of commonage, and the tenant farmer from the Basque provinces, Navarre, or the Maestrazgo only very occasionally experienced poverty, though they enjoyed little comfort. But the Galician peasant, on his tiny patch of land, was crushed by the weight of the foro, a survival from the seignorial taxes, and his counterpart from León, Old Castile, and the Aragon plain was too often struggling in the clutches of moneylenders. Although the peasant from the Levante sometimes managed to buy back the hereditary holding, subject to the payment of the censo, the farmer on the well-irrigated plains of Granada and Murcia had to pay enormous rents. The small Catalan proprietor enjoyed relative ease, but the condition of his neighbor, the rabassaire [10], had deteriorated in recent years.

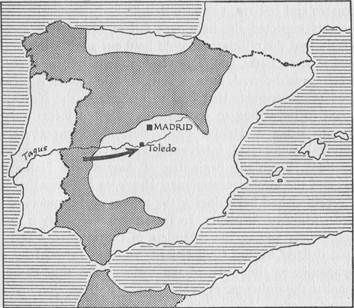

On the plains of New Castile, the estates of the aristocracy were nearly always rented out. The trouble here was the shortness and precariousness of leases, the absence of any obligation on the part of the landowner, who could raise his rents at will and often allowed his agents to abuse the peasants. According to the 1929 tax records, 850,000 heads of families out of a total of 1 million had a daily wage of less than one peseta.

In La Mancha and Estremadura, estates were larger and small cultivators less common. In the plains the typical peasant was the yuntero, a landless peasant with a mule team who cultivated the land of an absentee estate owner whenever he could.

Andalusia was the traditional domain of the latifundia. Here the average annual income of a big landowner was about 18,000 pesetas and a small one about 161 pesetas. But the majority of peasants did not own any land: they were braceros, day laborers who seldom worked more than one day in two and had to survive all year on starvation wages by working on the large estates in the worst of conditions [11], under the supervision of the labrador, the predatory bailiff, who was always ready to line his pockets through arbitrary fines or blackmail over jobs. Much arable land remained fallow, its owner either preserving it for shooting or because he was able in this way to make the braceros pay through the nose for their demands. For this region, which probably included some of the wretchedest people in Europe, was also the land of class hatred, of the slave ever ready to revolt against his master: the rebellious peasants were hungry for land.

In short, a handful of big landowners held sway in Spain. [12] The ‘oligarchs,’ as they were known to their enemies, had for centuries managed to preserve the majority of their privileges and their wealth at the expense of the peasant masses. Their regime had been the Monarchy, the only one in keeping with their interests and aspirations. It was to save it that they agreed in 1923 to the pronunciamiento that heralded General Primo Rivera’s dictatorship. In 1930, it was the general agreement between the King and the oligarchs that led to Primo’s dismissal and the summoning of General Berenguer. In 1931, the Republic was proclaimed without any violence: it was the ‘glorious exception’ of a ‘peaceful revolution,’ as the landowner Alcalá Zamora, the new president, described it over the air. The Monarchy made way for the Republic without seriously damaging the social and economic system. Alfonso XIII left Spain but did not abdicate. The vast majority of the oligarchs remained loyal to him. Under the new political system they preserved the solid pillars that had supported their dominance over the years: the Church and the Army.

The Spanish Church, which seemed to come straight from the Middle Ages with its 80,000 priests, monks, and nuns, was also an anachronism. Its spiritual and temporal power was considerable. However, it is difficult to assess its wealth accurately. It was almost certainly not the largest owner of land in the country, as has often been stated, but it was not far from it. The inquiry made shortly after the proclamation of the Republic attributed to it 11,000 estates, valued at some 130 million pesetas. Its urban properties were no less great, and it was a force in the business world, in banking as well as in industry, controlling directly or through puppets firms as important as the Urquijo Bank, the Riff copper mines, the railways of the North, the Madrid streetcars, and the Transmediterranean Company.

Under the Monarchy and to a large degree under the Republic, the Church still controlled education [13]: in a country with twelve million illiterate – half the population – its schools taught and educated five million adults. But this control over education was far from being matched by equal influence. The anti-catholic disturbances and the burning of convents and churches that occurred in May 1931 revealed a deep-rooted phenomenon: the popular masses were freeing themselves from the Church’s sway and were turning against it. [14] Here it is also interesting to note that the Church was still heeded by the rural masses only in the regions where social inequality was less pronounced, either because everyone there was poor, as in Galicia, or because the general level of existence was acceptable, as in the Basque provinces, Navarre, the Levante, Catalonia, and, to some extent, Old Castile. Elsewhere, in the Spain of the latifundia, the Church was regarded as an instrument of propaganda and the province of the rich, as the defender of property and an iniquitous social order, and as the determined foe of all social betterment, the enemy of the workers. Cardinal Segura, the Archbishop of Toledo, whose annual income was 600,000 pesetas, was a perfect example of the integrative, reactionary side of the Spanish Church. This prelate, primate of Spain, ‘a thirteenth-century churchman’ who ‘thought that a bath was the invention of heathens if not of the devil himself and who wore a hair shirt like an early monk’ [15], was the champion of unyielding opposition to the Republic, the resolute opponent not only of all ‘subversion’ but of all liberalism.

Unique in its structure and in its place in society, the Spanish Army had no equivalent in Europe. Although it was defeated regularly for a century while defending its remaining colonial possessions, it established itself as an autonomous political body. In short, it was a pronunciamiento army – it is no accident that this is a Spanish word. Repeatedly beaten and humiliated, the officers blamed their reverses on successive governments. The Riff war against the Moroccan leader Abd-el-Krim dragged on from 1921 to 1926: it cost Spain the lives of 15,000 soldiers in 1924 alone and was successfully concluded only by the intervention of Lyautey’s French troops. In spite of such disasters, the military leaders regarded themselves as the champions of colonial reconquest in the face of negligent governments, and it was in this role that Lieutenant-Colonel Francisco Franco, one of the commanders of the Spanish foreign legion, first appeared in the political arena. After the victory, Morocco remained the fief of the Army: the generals there behaved like veritable proconsuls.

An honorable outlet for rich men’s sons – the señoritos – the officer caste, jealous of its privileges, the most important of which was to ‘pronounce,’ was, in the view of traditionalists, the incarnation of every Spanish virtue. In the general morass, it was the only real weapon of the ruling classes, their final recourse and their supreme hope. The Republic had been proclaimed with the consent of the Army leaders. But the failure of the highly respected General Sanjurjo’s pronunciamiento on 12 August 1932 showed that this consent could be withdrawn at any time if the Republic decided not to fall in with the injunctions of the oligarchs. [16]

It is a remarkable fact that this army, whose artillery consisted of old 75-mm field guns, whose infantrymen were armed with 1909 Lebels, and whose planes could not have taken on any foreign air force, was plentifully supplied with machine guns. It would not have lasted a week against a modern army; it was still able to drown a revolutionary upsurge in a sea of blood. Ill-fed, ill-clothed, and ill-equipped, its recruits were also very poorly trained. Its officers were very mediocre technically, the most experienced being the colonial officers who had served in Moroccan units. Yet it had its élite, a genuine professional army, in the Tercio of the foreign legion, organized during the Riff war by General Millán Astray, its Moroccan regiments recruited from the most backward and most warlike mountain tribes. These mercenaries, legionaries and Moors, were the shock troops of the Civil War army. When the miners of Asturias rose up in October 1934 to prevent the Right’s accession to power, it was these élite units, unsympathetic to Hispanidad but efficient, that crushed the workers’ uprising in twelve days. In the front ranks were some of the officers sentenced for serving in the insurrection against the Republic that was led by Sanjurjo two years earlier.

However, this army was not short of officers. Under the Monarchy there were 15,000 of them, including 800 generals, that is, one officer to six men and one general to just under a hundred men. Under the Republic there were fewer and fewer Republican officers. The Azaña government, in order to free the cadres, offered full pay to anyone who applied for early retirement: many left-wing officers seized the chance of leaving the Army and its stifling atmosphere. The overwhelming majority of the cadres and all of the senior officers were resolutely Monarchist, supporters of the oligarchy, opponents of change, and deadly foes of the Revolution. [17]

The weight of the past lay even on the theoretically new forces of the young Spanish bourgeoisie. The industrialization of Spain had, as we saw, progressed very slowly during the nineteenth century and then only in geographically limited areas. This slow progress and localization explain the peculiar characteristics of the resultant middle class. It was only in Biscay and Asturias that a genuine financial oligarchy existed, as exemplified by the Banks of Biscay and Bilbao. The majority of historians have made a point of stressing the political circumstances of the emergence of this financial capitalism, which flourished after the defeat of the liberal movement by the agrarian oligarchy of the Restoration. Bourgeois liberalism not only suffered from the ineffectual implantation of the middle class in the country, it also labored under the handicap of always having been denounced by its opponents as a foreign product. At the height of the twentieth century, the liberal bourgeois had first to avoid being an afrancesado. [18] Suspected of being nothing but a mouthpiece for foreign ideas or a front for foreign capital, the Spanish bourgeois, in his concern to be accepted by the leading circles, was driven to further concessions, denials, and capitulations.

The millionaires of Bilbao and Asturias were anxious to join the landed oligarchy and to share with it the directorship of the Bank of Spain. [19] The new financial oligarchy was, from the outset, linked by a thousand ties, personal as well as economic, with the aristocracy. The Count of Romanones, one of the most prominent statesmen in the Monarchy, was a large landowner in the province of Guadalajara, the biggest apartment owner in Madrid, and a substantial shareholder in the Penarroya mines as well as several important banks. The bourgeoisie was therefore quite unable to provide the Spanish economy with the impetus necessary for a radical change, since this would imply an attack on the landed interests, which were ultimately only one section of a vast oligarchy of men of property.

This oligarchy found its most vigorous exponent, on the eve of the Revolution, in Juan March. A former smuggler, then director of the tobacco monopoly under Alfonso XIII, this powerful financier and industrialist, accused of treason and fraud by the first Republican government, was at one and the same time the owner of vast country estates, the confidential agent of British capitalist circles, president of the Central Office of Spanish Industry, where he sat alongside Romanones, Sir Auckland Geddes of the Rio Tinto mines, and representatives of Italian, French, and German capitalist interests. He put money into anything that was opposed to the Republic and played a decisive role in the events, both at home and abroad, that led up to the Civil War.

The Spanish aristocrat was very different from his English counterpart, who had succeeded in joining the tide of capitalist expansion. He was not particularly concerned with making his estate prosper as a business but was mainly occupied with preserving his seignorial authority over the cheap manpower that he believed was his right by birth. His only raison d’être was his caste, and he would have openly admitted that he was the very incarnation of Spain. Behind him were his ancestors, who had bequeathed him the inseparables of name, fortune, and authority.

The majority of the aristocrats were supporters of Alfonso XIII and of the Monarchy as a principle of social preservation. Under the Republic they supplied cadres for Renovación Española, which was, according to Ansaldo, a ‘legal cover for insurrection,’ led by Goicoechea and José Calvo Sotelo. The latter, on his return from exile, became the figurehead of a much more avowedly conservative party, ‘corporatist and authoritarian’ rather than Monarchist. Still young – he was born in 1893 – he already had a brilliant political career behind him. A deputy at twenty-five, he became governor of Valencia the following year, and then minister of finance under Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship. Through Balbo he was in constant touch with the Fascist government in Rome. Linked with all of the oligarchy’s influential circles, especially with Cardinal Segura, a self-confessed admirer of National Socialism and Fascism, he was a remarkable orator and a good journalist with a reputation as an economist. In the 1936 Cortes, he became the spokesman of the Extreme Right and one of the leaders of the Generals’ plot.

The Traditionalist Communion, the other Monarchist movement, unquestionably had a popular base among the small peasants of Navarre, led by a fanatical priesthood. The Carlist movement, born after the Napoleonic wars, had for more than a century been attracting the most fanatical Catholic Conservatives under the motto ‘God, King, and Country’ and plotted tirelessly to restore the ‘legitimate’ authority of its successive pretenders, the last of whom was the ageing Alfonso Carlos. Its true leader, Manuel Fal Conde, had for several years been systematically preparing it for an armed uprising against the Republic.

On 31 March 1934, Antonio Goicoechea for Renovación Española, Antonio Lizarza for the Carlists, and Lieutenant-General Barrera signed a pact in Rome with Mussolini, by which the Duce undertook to support their movement for the overthrow of the Republic by supplying it with arms and money. Between 1934 and 1936, many young men from the Carlist military organization of the Requetés underwent periods of military training in Italy. Stocks of arms were built up in Navarre, thanks to Italian funds. [20]

In fact, both Carlists and Alfonsists refused to bow to universal suffrage, the very conception of which was an insult to Hispanidad, and believed themselves to be entrusted with the providential mission of saving Spain and Christianity from the threat of subversion by liberals and revolutionaries.

The Church in Spain did not immediately respond to those of its members who wished it to follow in the tracks of the Monarchist conspirators. Apparently it was on the advice of the more politic Vatican that the subtler line of the Jesuits and their confidential agent, Angel Herrera, director of El Debate, prevailed under the Republic. The idea was to create, staff, and inspire a mass Catholic party, rejecting both the Monarchist and Republican labels, agreeing to participate within the framework of the parliamentary system but openly proclaiming its intention to abolish all reference to the secular state in the constitution. [21] Thus formed, Acción Popular was merely the entry into the electoral arena, in the guise of a reactionary and authoritarian party, of Catholic Action (Acción Católica), with its hierarchical leadership. Its head was José María Gil Robles, son of a Catholic barrister, brilliant pupil of the Salesian priests in Salamanca, and a journalist on El Debate. Chosen by Herrera to lead the party of the Church and the propertied class and married to the daughter of an extremely rich count, he had the qualities his role required: a good organizer, a capable orator, and not without a flair for action, he took for a model not Hitler, whom he disliked for his anti-catholic attitude while admiring him for his efficiency, but the Austrian Chancellor Dollfuss and his corporative state.

In 1933 he merged his organization with other right-wing groups to create the CEDA (Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas); this electoral alliance with the Monarchist groups won him enormous success. From 1934 to 1936 the CEDA was the heart of the coalition with the right-wing Republicans, who systematically destroyed every achievement of the first Republican government. These two years, christened the bienio negro (the two black years) by the Republicans and Socialists, led to the shelving of agrarian reform, the systematic reduction of wages, and the restoration of Monarchist officers, momentarily on the sidelines, to positions of authority. Ferocious in its repression of the Asturian miners, the CEDA left the coalition government when the president of the Republic refused to order the execution of González Peña, the Socialist leader who directed the uprising. It opposed even the modest reforms in favor of the yunteros proposed by one of its members, Jiménez Fernández, the minister of agriculture. [22] In 1935 it vied for the power that from then on it meant to wield alone.

The military conspiracy, on which the extremist elements were relying, burgeoned under the benevolent eye of Gil Robles, minister of war from 1934 to 1935. One of the first acts of the government formed after the 1934 elections was the proclamation of an amnesty for the troops implicated in General Sanjurjo’s 1932 pronunciamiento. Convicted and dismissed officers were rehabilitated. In 1934, on Sanjurjo’s initiative, the Unión Militar Española was formed; it very soon became the nucleus of a conspiracy in which most of the top leaders participated: General Franco, chief of staff, General Fanjul, undersecretary of state, and General Rodríguez del Barrio, Inspector-General of the Army, all Monarchists and Conservatives with positions of authority in the Republican Army. One of them, Lieutenant-General Barrera, in company with the Monarchists Lizarza and Goicoechea, signed the pact with Mussolini.

Under the nom de guerre Don Pepe, Colonel Varela – soon to be promoted to general – cemented relations with the Carlist leaders and supervised the military training of the Requetés in Navarre. In summer 1935, during the annual maneuvers in Asturias, Franco, Fanjul, and Goded, according to one of the movement’s official historians, laid ‘the groundwork for the preparation of a national uprising.’ The leaders of the Army were ready to move if Gil Robles’s party proved unable to seize power by means of elections.

The German and Italian examples led certain sections of the oligarchy to contemplate the use of political instruments more modern than the traditionalist parties.

Long before 1936, Juan March, the millionaire, had financed [23] a movement that was to play a leading role during the Civil War. In 1932 José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the dictator’s son, founded the Falange Española, which became the Falange Española Tradicionalista in 1934 when it merged with the Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista (JONS), and which remained a tiny group without real influence until after the February 1936 elections.

The Falange’s twenty-six-point program was typically Fascist: it reproached the Republicans for their timidity toward the oligarchy, advocated nationalization of the banks and railways and radical agrarian reform, but at the same time denounced the corrupt and disruptive Marxist doctrine of class struggle and countered it with the ideal of ‘harmony between classes and professions in a unique destiny,’ that of the Fatherland and Europe. Only in its attitude toward the Church was the Falange different from Mussolini’s Fascio: a Falangist, even an atheist, respected in the Catholic Church the historical ideal of Spain. [24] The successes of Hitler and Mussolini seemed to José Antonio’s supporters to guarantee rapid victory, and their dreams of an empire turned them toward French Morocco and the restoration of sovereignty over South America, that other product of Hispanidad and the ‘common destiny.’

The founder and leader of the Falange, José Antonio, as he was known, was a young Andalusian of great charm, with all the qualities of youth in his favor, undeniably elegant in appearance, and even quite generous, which meant that many of his fiercest opponents found it hard to resist a natural liking for him. Nevertheless, his movement was not yet taken seriously. Like Fascism and National Socialism, Falangism had only been placed in a ‘social’ context in order to combat the Marxist organizations and oppose them with the weapons of terror and violence. Until 1936 the Spanish oligarchy remained cool toward this apparently plebeian movement and preferred to look to Gil Robles for a victory to be won within the legal framework of elections: it was not yet ready to accept the disadvantages of being saved by a party with Fascist methods and doctrines, often as harsh with its allies and supporters as with its opponents. In February 1936 the Falange had only a few thousand members, a thousand of them in Madrid. It entered the elections alone and was resoundingly defeated. It remained a reserve force, ready for use if the working classes threatened to take to the streets again. José Antonio, who had met Mussolini too, was at any rate in close touch with the military and political leaders of the plot.

The forces that could have countered such threats were weak and, more important, divided.

It was one of the tragedies of the Spanish Liberals and Republicans that, in spite of the existence of a Basque and a Catalan bourgeoisie, the incompleteness of the Spanish nation and the persistence of autonomist leanings had hindered the formation of a genuine Spanish bourgeoisie. The bankers in the Basque provinces and the biggest Catalan businessmen were hand in glove with the oligarchy. All the petty-bourgeois elements, which in the Western countries served as the base for the parties most strongly drawn to the parliamentary system, had turned toward Autonomist movements.

Included in them were barristers like Manuel de Irujo and Leizaola and industrialists like José Antonio Aguirre y Lecube, who in 1936 led the Euzkadi Nationalist party [25], founded in 1906 on a racial, political, and religious basis that its motto expressed perfectly: Todo para Euzkadi y Euzkadi para Dios. The country priests gave solid support to the determinedly conservative Basques. The capitalists were glad to subsidize an antisocialist party that had managed to rally strike-breaking Catholic trade unions and ‘Solidarities of Basque Workers’ against the UGT and the trade unions adhering to the ideology of class struggle, a party that acted as a solid rampart protecting both the Church and the propertied classes. In the early days of the century, the industrial development of Biscay, though continually a prey to the incompetence and corruption of the oligarchical state, increased the attraction of the nationalist ideal, firmly rooted in the ancient traditions of a people that was indisputably unique and proud of it.

Under the Republic, the Basque Nationalists, naturally enough, made common cause with the Right and the conservative and reactionary parties. But in November 1933, the majority of the Right having rejected the autonomous status provided for the Basque provinces, the party was forced into opposition and into a de facto alliance with the left-wing Republicans and Socialists.

A similar phenomenon occurred in Catalonia. Here too autonomism was fostered by the industrial revolution and conflict with the retrogressive agrarian oligarchy. The upper bourgeoisie of course remained cautious: it needed the Spanish market and the support of the central government against a restless proletariat. Its leaders, Cambó and his friends in the Lliga, were more oligarchical than Catalan. But the petty bourgeoisie did not have the same reasons for caution once it was clear that Catalanism could only succeed if it enjoyed the support of the workers and peasants. Moreover, its party, the Esquerra, was a party of the masses; it was started in April 1931 by an alliance between different Republican parties and groups in Catalonia, and it leaned on the powerful peasant trade union, the Rabassaires. Its prime mover and inspiration, Luis Companys, once linked with Salvador Seguí, was for a long time the legal representative of the CNT, with which he remained in close touch. The Republic was proclaimed in Barcelona before it was in Madrid, and the status of autonomy for the province of Catalonia was voted on 15 September of the same year. But in 1934 autonomy was revoked, because the Autonomists, disquieted, had launched and bungled an uprising against the Right. The Catalan Autonomists found themselves in prison alongside the militant workers.

Apart from a few towns and the rich, irrigated plains of the Levante, nowhere in the rest of Spain was there a genuine base for the bourgeois Republican parties. Alejandro Lerroux’s Radical party stood for the aspirations of the petty bourgeoisie hostile to the Army and the Church and typified its desire to see the creation of a new Spain, freed from the shackles of the feudal era, opening the way to creative capitalist expansion. But, terrified by worker and peasant unrest, the Radicals very soon drew back and, in 1933, through fear of revolution, opted for an alliance with the CEDA, with which they shared governmental responsibilities. Lerroux’s party was totally discredited as the result of a financial scandal in 1935. [26] Part of his staff, behind Martínez Barrio, a worker’s son and a leading freemason, then joined Manuel Azaña’s left-wing Republicans, who differed very little from them.

Premier from October 1931 until the victory of the Right in the 1933 elections and president in 1936, Azaña was, for the record, a typical Spanish Republican. Born in 1880 in Alcalá de Henares into a well-to-do family, a brilliant pupil at the Augustinian college at El Escorial, which did not in the least prevent him from being fiercely anticlerical, he was for a long while attracted more by literature than by politics. President of the Madrid Atenéo, he played an important part in the Republican opposition at the end of the Monarchy and very quickly made his mark in the Cortes at the head of a group of deputies in Acción Republicana. An admirer of bourgeois France, he dreamed of an orderly and well-balanced republic, led by eminent men and firmly based on a middle class of peasant proprietors. Worker-peasant unrest did not drive him into the arms of the Conservatives. It persuaded him, on the contrary, of the need for the Republicans to give priority to a program of reforms capable of winning over enough workers to check the revolutionary movement.

His first government was a profound disappointment to those who had expected nothing from the Monarchy but who were in a mood to expect everything from the Republic. The agrarian law attacked only the problem of the latifundia, neglecting the urgent question of the precarious lives of the small peasants. In two years, only 12,000 peasants out of the millions hungry for land received a plot, which they had to pay for as well, since the big proprietors were given compensation.

The reform of the Army merely led to the departure of the Republican officers, only too glad to leave the cadres on full pay; the Monarchist leaders remained in their jobs. Efforts by the Azaña government in the field of social reform were completely frustrated by the effects of the world crisis on the Spanish economy. Its anti-catholic legislation antagonized a large section of the middle classes without making a serious breach in the citadels of clericalism. Above all, order was more firmly maintained in the face of worker and peasant unrest than against the Monarchists. The Law for the Defense of the Republic permitted a repression that was no less severe than the Monarchy’s. The Civil Guard, inherited from the Monarchy, remained intact. It was duplicated by another police force, recruited from among Republicans, the Guardia de Asalto (Assault Guard), no less energetic in its handling of the workers and peasants.

In January 1933, prompted by Anarchist militants, the peasants of Casas Viejas in Andalusia rose up and proclaimed ‘Libertarian Communism.’ Azaña and Casares Quiroga, his Galician minister of the interior, carried a large part of the responsibility for the repression that followed: the Civil Guard killed twenty-five braceros and burned their houses. When Azaña relinquished power, the tally of his struggle against worker and peasant agitation was a heavy one. The prisons were full of militant revolutionaries: 9000, mostly Anarchists, according to official documents. It was this aspect of his government that enabled another Republican, even one as moderate as Martínez Barrio, to say that the regime drawing to a close was one of ‘mud, blood, and tears.’

Discredited after his stay in power, Azaña gained back some of his popularity as a result of persecution by the Right. Although he had had no hand in the October 1934 uprising, he was pursued and imprisoned: thus he recovered in opposition the prestige he had lost when in power. Leader of the Republican Left, this ‘small, squat’ man, with a greenish, bilious complexion and ‘fixed, expressionless eyes’ [27], whom his opponents liked to compare to a toad, was a good parliamentary speaker but a poor democratic leader. Yet 40,000 persons flocked to a meeting at Comillas near Madrid after his release, at which he spoke in support of the political prisoners. This was because once again he symbolized union between Republicans and Socialists, the parliamentary Republic that appealed to the workers to support it for the sake of a restored and modernized Spain, freed from the oligarchy.

It was over this question that a split occurred in the ranks of the bourgeois Republicans. Lerroux opted for an alliance with the CEDA for fear of working-class revolution. Azaña and Martínez Barrio chose to join with the workers’ parties and spare Spain a revolution. They felt that the constitutional framework provided every chance for deep-rooted structural reforms. The Cortes, the only chamber elected by universal, secret, and direct suffrage by citizens of both sexes, was able to provide safe majorities, thanks to the electoral law that gave 80 percent of the seats to majority lists in regional divisions. The president’s sweeping powers – the right to choose and to dismiss the premier and to veto laws – and the existence of the Tribunal of Constitutional Guarantees looked at the same time like a guarantee against intrigue. Within this context they hoped to complete the work, barely adumbrated in 1931, of constructing a genuinely liberal, secular, democratic state and of regenerating society by an agrarian reform that would grant estates to millions of landless peasants.

They could not hope to fulfil such a task without the support of the labor movement, with its trade unions and parties. In the course of the century this movement had become a decisive force whose influence had been deeply felt in the very heart of Spain, in the peasant world. Of course, the peasants of Euzkadi remained attached to their traditions and to the Nationalist party, the Navarrese and the people of the Maestrazgo formed the popular basis for Carlism, and the small peasants in Catalonia and the Levante readily voted for the Republicans, both Right and Left. But the influence of the Socialists in the Asturian countryside, among the agricultural workers of Old Castile, and among the well-organized farmers in the huertas [28] of Granada and Murcia was appreciable. It was the Anarchists who organized and inspired the struggles of the subforados [29] in Galicia, the revolts of the Andalusian braceros, and the battles of the landless peasants in Aragon. The labor movement was busy winning over the peasant class. It became both an enemy and the stake of the game. Even its most moderate claims posed a direct threat to the vital interests of the oligarchy.

Because it was a tremendously explosive force, the Republican petty bourgeoisie sought its friendship and its support for its own ends. In the face of formidable enemies, it was indispensable to have the labor movement as an ally, in order to achieve in rural Spain the revolution that the country was yet to experience and without which no serious social and economic progress seemed possible. But the Spanish labor movement had its demands and its objectives too. By the end of 1935 it seemed ready to challenge the oligarchs, who wished to destroy it, as well as the Republicans, who were planning to use it.

The Spanish labor movement had a unique character too. In the other European countries the struggle between Marx’s supporters and Bakunin’s that began during the First International ended in the victory of the former, then known as the ‘authoritarians’; they formed the social-democratic parties affiliated with the Second International and the reformist trade unions. In Spain, on the other hand, the victory of the Libertarians, Bakunin’s friends grouped in the secret society of the ‘Alliance of Socialist Democracy,’ had lasting consequences, branding the Spanish labor movement for a long while with the revolutionary stamp of Anarchist and Anarcho-Syndicalist traditions.

There was nothing surprising about this victory; in an agricultural country where so many ties linked the industrial worker with the landless peasant and the day laborer, where peasant riots, short, violent revolts, and banditry by outlaws were the time-honored form taken by popular explosions of anger and revenge, Bakunin’s ideas fell on fertile ground.

In his view, in fact, only the spontaneous unleashing of the forces of the oppressed could overthrow capitalism, with energetic action by an organized minority intervening only in order to coordinate the efforts of the masses in their uprising against the forces of repression. To political action by parties, which appealed to more advanced countries, Bakunin and his friends preferred insurrection and the glamor of revolutionary example, more in line with Spanish traditions of class struggle. Thus it was that, in their work of emancipation, they attributed a decisive role to the ‘much-loved bandits,’ to the ‘avenging angels of the poor,’ whom the Spanish peasant both loved and feared. [30]

Fierce opponents of the state as the ancient form of oppression, Bakunin’s disciples, rejecting ‘any organization of a so-called provisional or revolutionary political power [31], saw the germ of the just and brotherly society of the future in the ‘free commune,’ so akin to the medieval peasant communities in which every revolutionary in Spain recognized his ideal.

The influence of Anarchist theoreticians, such as the famous teacher Francisco Ferrer and especially Anselmo Lorenzo, and of the influence of the Syndicalists of the French CGT combined in 1910 to produce, from a basis of Catalan Libertarian cells, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), a Syndicalist organization that the repression could not prevent from leading the great wave of strikes in Catalonia in 1917.

Briefly tempted to join the Communist International, as had been proposed by two of its leaders, the schoolteachers Andrés Nin and Joaquín Maurín [32], who had been sent by it to Moscow and converted to Communism, the CNT held aloof after the events of Kronstadt. In its bastion in Catalonia, it had to carry on, in the years to follow, a bloody struggle against the governor, Martínez Anido: hundreds of militants fell to the bullets of the pistoleros, among them the general secretary of the CNT, Salvador Seguí. [33]

It was under Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship, at the height of the repression, that the FAI, the mysterious and powerful Federación Anarquista Ibérica, came into being in 1927. Very soon, it dominated the CNT completely. A clandestine organization along the lines of the Alianza, made up of kindred groups similar to Masonic lodges under the authority of a secret Mainland Committee, the FAI very quickly became the heart and soul of the Anarcho-Syndicalist union.

It was not merely an active, anonymous group but a typically Spanish state of mind. This was what the French trade unionist, Robert Louzon, friend of and sympathizer with Spanish Anarcho-Syndicalism, wrote: ‘“FAIism” is peasant rebellion raised to the level of working-class struggle by the peasant masses, joined, of course, in Spain as elsewhere, by the workers, and which is to some extent systematized and “theorized”. [34] The FAI adopted the revolutionary methods preached by the Italian Anarchist Malatesta: ‘Seize a town or a village, render the representatives of the state harmless, and invite the population to organize itself freely.’

It was at the instigation of the FAI that brief revolts broke out, violent local and regional flare-ups establishing a short-lived Libertarian Communism: at Llobregat in January 1932, at Casas Viejas in January 1933, and in Aragon in December 1933. It was the FAI that dissuaded the CNT from any entente with the Republicans or Socialists and that kept up, in the union’s propaganda, the fierce hostility of the Anarchists to electoral and parliamentary ‘trickery.’

Not all Syndicalists were prepared to accept FAI domination. In 1931, many of the leaders rose up against the adventurist and ‘putschist’ policy that it imposed on their union. Well-known leaders, such as the former secretary-general, Angel Pestaña, chief editor of Solidaridad Obrera, Juan Peiró, and Juan López called for a return to more genuine Syndicalist action, involving less indifference to immediate claims and more long-term prospects of action. When their group, known as the treintistas, was expelled from the CNT, it formed ‘opposition unions’ that had some influence in Asturias, in Levante, and in a few towns in Catalonia. The supporters of the FAI accused them of having gone over to reformism: in 1934 they took part in the insurrection in Asturias and Catalonia, while the CNT and the FAI held aloof.

On the eve of the Civil War, the FAI seemed to be completely incorporated into the confederal organization, as witnessed by the ever-linked initials CNT–FAI and the red and black colors of the flag. Yet, led by Peiró and López [35], who always spoke up for the independence of the unions in regard to any political group whatsoever – including the FAI – the opposition unions reinstated the CNT. The Saragossa Congress in March 1936 solemnly reaffirmed its aim, which was the establishment of Libertarian Communism. However, the FAI ideology had taken a step backward: the CNT in February had not given the cue to boycott the elections, and the restored treintistas won acceptance for their point of view more than once in the weeks that followed.

Whatever the CNT’s indisputable difficulties, the fact remained that, through its loyalty to the principles of class struggle and direct action [36], it had maintained a militant and combative working-class base, with some very tough strikes to its credit: the Felguera metalworkers held out for nine months, and in 1934 the Saragossa workers sustained a general strike for six weeks. More important, the Anarcho-Syndicalist tradition made the unions in Spain far more than a defensive weapon in the daily struggle; they became a living cell in the social organism, often monopolizing the worker’s entire leisure. Furthermore they monopolized what was the revolutionary means par excellence, the instrument of social change: class solidarity, infinitely more influential in this respect than the political parties.

Yet this highly active organization had obvious weaknesses. Faced with the complexities of a modern economy and the interdependence of its different sectors, the CNT’s political and economic theories seemed highly ingenuous. Everything was simplified to an extreme by the pens of propagandists describing the idyllic ‘commune’ whose budding and later flowering would be made possible by militants willing to sacrifice their lives for it. It would seem that for some people nothing had changed since Malatesta, and that in their view it was no more difficult to establish Libertarian Communism on a permanent basis in the whole country than it had been to establish it for a few hours in Llobregat or in Figols.

However, it was not the theoreticians who emerged as leaders among the Anarchists. It would be hard to define the roles of personalities as different as Federica Montseny, a tireless woman speaker and propagandist, the formidable journalist Diego Abad de Santillán, an exotic pseudonym that was said to conceal an Argentinian militant [37], or the invalid Manolo Escorza del Val, physically weak but morally implacable, who prompted the FAI’s Mainland Committee and the CNT’s Defense Groups from the sidelines. They were all equally representative of the diversity of the Spanish Liberation movement. However, not one of them achieved the notoriety of Buenaventura Durruti.

Durruti was born in León on 14 July 1896, into a family of eight children. His father worked on the railroad. At fourteen he was a mechanic in a railroad workshop. After taking an active part in the 1917 strike, he was forced to leave for France, where he worked for three years. He then returned to Spain, joined the CNT, and became an Anarchist. It was at this point that he went to Barcelona, the heart of the movement. There he joined the Los Solidarios group and those who were to be his companions in a life of struggle. Durruti, Jover, Francisco Ascaso, ‘a little dark man of insignificant appearance’ [38], and José García Oliver, the most ‘political’ of the four, became the ‘Three Musketeers,’ legendary heroes of Spanish Anarchism. Terrorists and marauders, they seized a Bank of Spain bullion van in order to finance the organization and helped to prepare the attempt on the life of Dato, the premier. Durruti’s involvement, confirmed by most of the biographical notes written about him after his death, seems to have been only ancillary. Federica Montseny informed us after our first edition was in print that the preparation of the attack on Dato was in fact the work of Ramón Archs, who died under torture. One of the instigators of the attack is still alive. One of the participants, Ramón Casanellas, had to seek asylum in Russia and was converted to Communism there before dying in a motorcycle accident. It was Ascaso and Durruti who killed Cardinal Soldevila in Saragossa to avenge the death of Seguí. After seeking refuge in Argentina, they were accused of terrorism and theft and once again had to flee. They crossed South America before going underground in France, where they were arrested just as they were putting the finishing touches to plans for an attack on Alfonso XIII. They spent a year in jail, threatened with extradition. Freed as the result of a left-wing press campaign, they resumed their nomadic life, refusing the political asylum offered them by the USSR. Returning to Spain after the fall of the Monarchy, they were again arrested in 1932. Before his deportation to Africa, the imprisoned Durruti managed to arrange for the judges to be burglarized and the evidence for a trial in which other Syndicalist militants were involved to be destroyed. Back in Barcelona after his release, he was playing an active part in the textile union when the Civil War broke out.

To some an indomitable hero, to others a killer, what was the truth about this man with the Herculean build, with the terribly expressive face, ‘a fine, imperious head eclipsing all others’? [39] According to his friends, he ‘laughed like a child and wept before the human tragedy.’ [40] No doubt that was why so much love and hatred were lavished on this symbol of Spanish Anarchism who exclaimed at the height of the Civil War: ‘We are not in the least afraid of ruins ... We are going to inherit the earth ... We carry a new world in our hearts, a world that is growing at this very moment.’ [41]

The opponent of this undeniably unique Anarchist movement was a Socialist movement of a far more classic type. Spanish Socialism was in fact only one of the branches of European Socialism, its particular features deriving mainly from its comparatively late development and its prolonged minority position within the labor movement.

The small group of authoritarians expelled in 1872 by Bakunin’s friends from the Spanish branch of the International became the nucleus of the Partido Democrático Socialista Obrero, founded in a café in 1879 by five friends. Through José Mesa and Paul Lafargue this small group, dominated by the remarkable personality of Pablo Iglesias, was strongly influenced by Jules Guesde and his rigid Marxist orthodoxy. Legalized in 1881, the young party had barely more than a thousand members and had to wait until 1886 before bringing out its first organ, the weekly El Socialista. This was because the conditions in which elections were held in Monarchist Spain and the total absence of social reform were not very favorable to the development of Socialist organizations linked with parliamentary and municipal activity and the struggle for reform; whereas the Anarchists, already in the majority in the working class, derived additional arguments for their cause from them. However, its minority position, together with the need for tirelessly explaining and convincing new members one by one, gave the Socialist organization a remarkable discipline and cohesion, as well as a lofty sense of mission and a determination to preserve the purity of its doctrine, perfectly embodied in the severe, handsome, forbidding figure of Pablo Iglesias. In 1888, two Socialist leaders, Mora and García Quejido, had founded the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT). Centralized, moderate, and overtly reformist, the new union, founded with just over 3,000 members, took more than eleven years to double its numbers.

Yet since the beginning of the century, the Socialist party and the UGT had been losing their original sectarian nature and had gradually become mass organizations. In Madrid, the original nucleus of printers rapidly spread to all the guilds. The success of the strikes by the Bilbao metalworkers, due to Socialist leadership in the UGT, established its influence there and formed a solid bastion in the region. The widespread establishment at that time of the casas del pueblo (Socialist clubhouses) made the Socialists the educators of thousands of militant workers. Also, before World War I, the UGT made gains at the expense of the Anarchists almost everywhere except in Catalonia. It played a prominent part in leading the 1917 strikes, and in 1918 already had more than 200,000 members.

The problem of whether or not to support the Third International dealt a harsh blow to the Socialist party. The events of 1917 in Spain had seemed to justify those Socialists who denounced the parliamentary path as a snare and an illusion. The Russian Revolution fascinated the militants.

Finally, after two contradictory decisions taken by two extraordinary congresses and the dispatch of two envoys with differing views to Moscow, a third extraordinary congress decided, by 8,880 votes to 6,025, to reject the twenty-one conditions for adherence to the Third International. Mora and García Quejido, the founders of the UGT, and Daniel Anguiano, back from Moscow, then broke with the organization, taking with them nearly half the militants, and together with Andrés Nin, Maurín, and the other CNT members who had been converted to Communism they formed the Spanish Communist party.